Published

Trade Relationship Status: Open

By: Oscar Guinea Vanika Sharma

Subjects: WTO and Globalisation

If international trade had a Facebook profile, its status would be ‘in an open relationship’. On average, a country trades goods with 164 other countries and these goods are bought and sold by thousands of firms. While some of these trade relationships may be long-term, most don’t become more than a summer fling.

Usually, trade relationships between firms are rather short-lived. Fugazza and Molina (2011) found that on average 3 out of 5 new trade relationships fail within the first 10 years – less than the average length of a marriage in France. Corroborating Fugazza and Molina’s results, Besedeš and Prusa (2006) studied the duration of US imports and found that the median duration of exporting a product to the US is very short – close to only 2 to 4 years. Finally, Nitsch (2008) studies the duration of German imports and found that the majority of trade transactions are short-lived (between 1 and 3 years). However, there is also a sizable fraction of bilateral trade that lasts for more than a decade.

Anyone buying or selling goods abroad knows that trade relationships are fluid. While companies might have a few long-term partners – other firms that they can rely upon – nothing precludes them from starting a new adventure. Business relationships are formed and broken constantly; some endure, others don’t, depending on the ever-changing business climate the companies operate in. That’s one of the beauties of free trade. It is dictated largely by a continuous cost-benefit analysis between companies rather than historic ties between countries.

The world of trade policy-making, or at least its press-releases, tend to have a more traditional take on how trade operates. Countries are keen to stress their special relationship as the most important trading partner or the largest exporter to another country. On other occasions, countries prefer to put themselves first and work on their strategic autonomy.

These aren’t useful statements. Trade between firms is less like the love between albatrosses – whose pairs stay together until one of them dies – and more like Tinder – always swiping to find more profitable relations. It is true that some countries may have more important trading partners than others. For instance, in our previous blog, we showed that the EU and China were the largest global suppliers of close to 3,000 goods (63% of all analysed products). But being the most important trading partner doesn’t make you the only one. Trade happens between firms not countries, and firms are always open to new business opportunities.

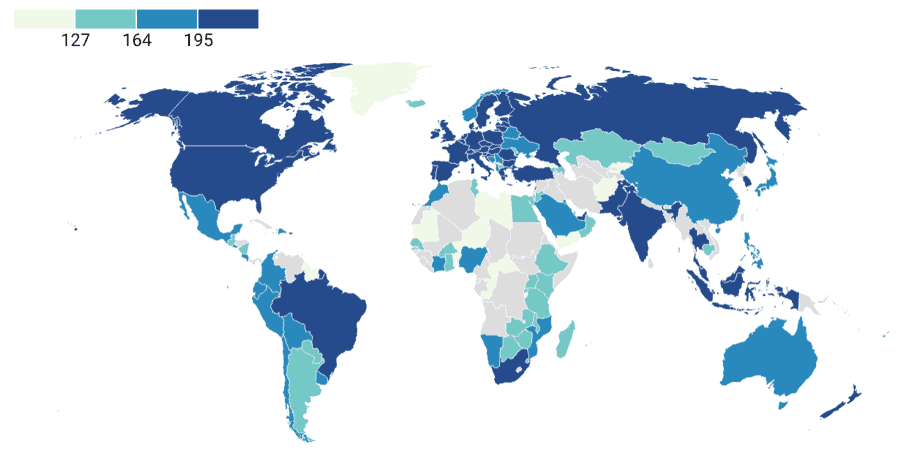

The map below shows the number of trading partners – for both, imports and exports – for several countries in the world. In 2018, the country with the fewest number of trading partners was Libya which imported goods from 72 countries and exported goods to 52 countries. The most promiscuous country was the European Union, importing and exporting goods with 210 other countries and customs. However, other large economies such as the USA, China, and the UK were also close to this number with 198, 190, and 206 trading partners respectively. Developing economies, particularly in South-East Asia such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, were also closer to the EU rather than Libya. They all had relationships with more than 200 partners – which supports the rapid economic growth these economies have seen in the past few decades.

Figure 1: Number of trading partners (imports and exports in 2018)

Source: UN Comtrade, Authors’ calculations.

However, one question remains: has it always been like this – have countries always had a large number of trading partners, has the world trading system veered from monogamy to polyamory?

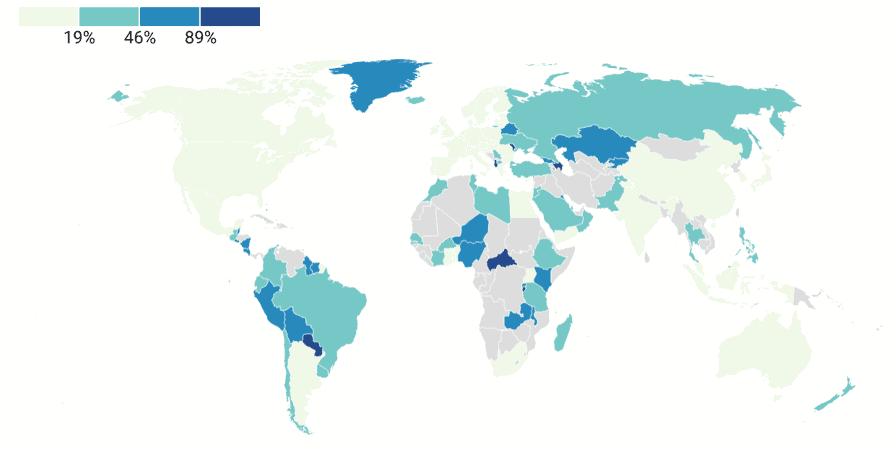

The next map shows the percentage change in the number of trading partners – for imports and exports – between 1998 and 2018. The light green colour shows the countries with a smaller increase in the number of trading partners while the darkest colours show the countries with the largest increase in trading partners. On average, countries have seen a 32% increase in the number of trading partners over the 20-year period. The world has in fact become more open, establishing multiple new relationships instead of building on just a few. Only Yemen – a country suffering from a brutal civil war – saw a fall in the number of trading partners, while the remaining 121 countries gained new partners. Smaller economies such as Seychelles, Paraguay, Comoros, Brunei, and Albania saw the largest expansion in their trade relationships with an increase of more than 100%.

Figure 2: Percentage change in the number of trading partners (imports and exports between 1998 and 2018)

Source: UN Comtrade, Authors’ calculations.

Unlike how policymakers portray trade relationships – as a symbol of the mutual importance two countries have for each other, a sort of marriage – the reality is that trade relationships can be short-lived, built on rapidly changing business decisions. Borrowing a quote from Alfred Tennyson, it’s better to have traded and lost, than never to have traded at all.

Still, there is a strong disconnect between how trade actually happens and how countries prefer to portray it. Trade as it exists between businesses is dynamic and business partners change often. This fluidity is guided by, and guides, several positive aspects of the economy including competition and innovation. On the other hand, countries are increasingly looking at trade as a tool of strategic importance – to create dependencies and place themselves in positions of power. The growing portrayal of dependency from trade and globalisation and the urge to build autonomy needs to be put into the actual context of who performs trade – which are firms not countries, businessmen and women not politicians or policy-makers.

The data shows that, over the time, business relationships have flourished, as more and more firms buy and sell products from multiple countries. And with increasing interconnectivity and the ability to work remotely, trade relationships may continue to expand in the future. Trade, like love, is an untamed force. When we try to control it, it destroys us. When we try to imprison it, it enslaves us[1].

[1] Paulo Coelho, The Zahir (2005). The full quote is as follows: “Love is an untamed force. When we try to control it, it destroys us. When we try to imprison it, it enslaves us. When we try to understand it, it leaves us feeling lost and confused.” As analysts, trade data also makes us feel lost sometimes but we always do our best to understand and interpret the data to the best of our ability.