Published

Who is Afraid of Global Trade?

By: Vanika Sharma Oscar Guinea

Subjects: WTO and Globalisation

There is a growing narrative in international trade that globalisation is causing increased concentration of production and that countries are relying too much on foreign imports.

One of the clearest examples of this is the widespread impression that, nowadays, everything is made in China. With the explosive growth of China’s goods exports from $63 billion in 1990 to $2.5 trillion in 2018, it’s not surprising that many jump to that conclusion. The Covid-19 pandemic has also exaggerated these concerns. The shortages of medical equipment or export restrictions in vaccines have given the impression that governments cannot rely on international markets. For instance, the US will start subsidizing the production of medical protective equipment. And more recently, the EU also increased its control over its exports of the Covid-19 vaccine looking to make sure that its domestic needs are fulfilled first. In a similar vein, with increasing domestic infections, India has banned the export of the Covid-19 treatment drug Remdesivir “till the Covid-19 situation in the country improves”. An argument can be made then, that some economies fear that countries could use their economic upper-hand as world exporters of a particular product to cut off supplies in order to push forward their own geo-political agenda.

If we step beyond emergency situations, the reality of global trade is actually quite different. Trade isn’t very concentrated. Let’s consider some data points.

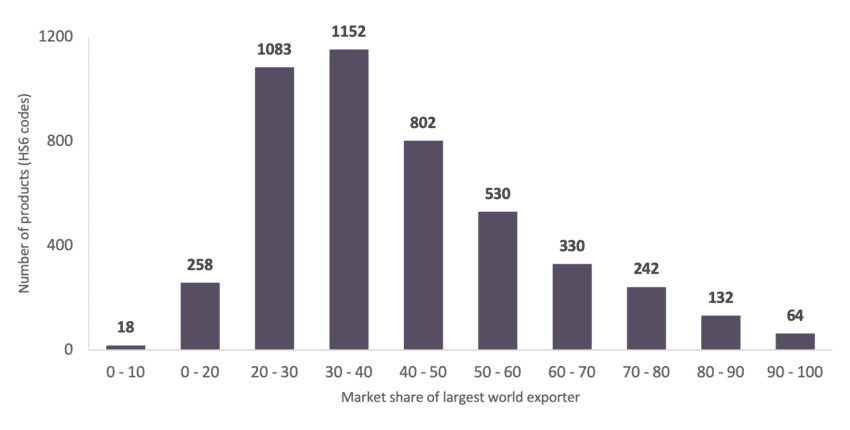

Figure 1: Market share of largest world exporter by product

Source: UN Comtrade, Authors’ calculations.

Source: UN Comtrade, Authors’ calculations.

We studied the share of the largest exporters in world trade for all products in 2018, in order to produce the graph above. The total number of products were 4,611 and we looked at the export values of the 50 largest economies in the world, taking the EU as a single country. For each of these products we first found the largest exporter, followed by their share on total trade in each product, and then grouped together the products whose share of the largest exporter fell in a particular bracket (0-10%, 10-20%, so on).

On analysing these shares through the graph, we found that for a large majority (72%) of the products, the share of the largest exporter in the global export of the product was less than 50%. Exports in these products (the 72% of all products) represent 77% of all total global exports (in terms of value of exports). Only for 4.2% of the products was the share of the largest exporter between 80% – 100%, representing 2% of all total global exports (in terms of value of exports). The graph clearly shows that for most products, there is no over-dependence on a single exporter, but rather diversification in where that product is coming from.

But still, there were a number of products for which the largest exporter supplies most of the world markets. A majority of these products however consist of either specific agricultural products which only grow in a certain region, such as maple sugar from Canada and sugarcane from Mexico, or different textiles made in different parts of the world, such as silk from China and artificial yarn from Japan. Some of them are also minerals or chemicals that can only be extracted from a particular geographical location, such as sandstone from India and ammonium chloride from China. While it is true that the lack of diversification in the production of some products may lead to global bottlenecks in supply chains if that product is produced in one location and that location is hit by a natural disaster or firms are under political pressures, the data show that this is the exemption rather than the norm.

Another important observation from our analysis is that the EU and China both came on top as the largest suppliers for most products. Out of the total 4,611 products, the EU was the largest world exporter for 1,380 products and China was the largest world exporter for 1,579 products, representing 29% and 34% respectively. This goes on to highlight that the EU – which is currently reviewing its trade dependency and, according to some EU leaders, should rely more on domestic supply – has much to lose if there is a global effort to reduce dependency on the largest exporter. Clearly EU relies heavily on exports – 36 million jobs and 17% of EU GDP depend on EU exports to the rest of the world – and it is also the largest supplier for many countries. If the EU cuts it dependency on the rest of the world, the rest of the world is going to cut its dependency on Europe.

So, there is still significant diversification for most products. It is this diversification in the trade regime, that is helping us overcome the current crisis. As shown in an ECIPE policy brief by Johan Norberg, the Covid-19 pandemic did not affect every region simultaneously; due to which when one region was in crisis, the other was open and able to supply them with important goods and vice-versa. Had the world been completely dependent on local supply chains, we would have been more vulnerable – not less.

Moreover, it’s not just big events like Covid-19 that have the power to change the world. Small policy changes can have large consequences too. Relatively small changes in economic policy have the capacity to tilt the world towards more protectionism. If that happens, every country will be worse-off, including the EU, which inadvertently may have kick-started this process with a more defensive trade and industrial policy whose impacts will ripple through the world economy as other countries respond to these changes with more protectionism.

I wonder if you could study this system as a network where countries are the nodes and edges represent trade volumes and types. An analysis of the structure of the network in terms of measures of connectedness and clustering might be quite informative about the resiliency of the system.

Thank you wonderful narration. However, if you observe the intra- trade among the Brics countries 55-60 percentage goods comes from China and moreover, these countries are highly dependent on China

Great analysis! it would be good to have a similar study on international trade in services, should statistics allow. Services represent +/- 25% of world trade and is absent from your study!

Thanks Pascal. I’m glad you liked the post. Your suggestion is a very good idea. Noted for future blogs.

Thanks for the insightful analysis.