Published

Rules Without End: EU’s Reluctance to Let Go of Regulation

Subjects: European Union

The goal is to increase competitiveness, and for that, Europe needs to reduce the volume of regulation and improve its quality. This is one of the points emphasised by Mario Draghi, who on 9 September presented his report on the challenges facing the European economy. The question is: can the EU regulate less and regulate better?

The EU has been a force for deregulation for years. It removed regulatory barriers that kept EU member state’s markets apart until the four freedoms became, more or less, a reality. The Single Market is one of the EU’s most impressive economic achievements and a driver of its prosperity, as highlighted by Enrico Letta. As a result of these efforts, in some economic sectors, the EU Single Market is as integrated as the US internal market. Take the OECD Product Market Regulation (PMR) indicator, which measures the degree to which policies promote or inhibit competition. A higher OECD PMR score indicates a more restrictive regulatory framework. Between 1998 and 2013, the EU’s PMR dropped by 40 percent, whereas in the US, it decreased by only 2 percent.

Then something happened. Worried about the potential fragmentation of the Single Market, the EU took on the task of drafting regulation for the entire union. In addition to long-standing policy areas such as agriculture, energy, telecommunication, transport, and financial services; it began regulating all aspects of life: consumer protection; climate policy, the circular economy; digital markets; technology – the list goes on. When it comes to regulation, the EU has become part of the problem rather than the solution.

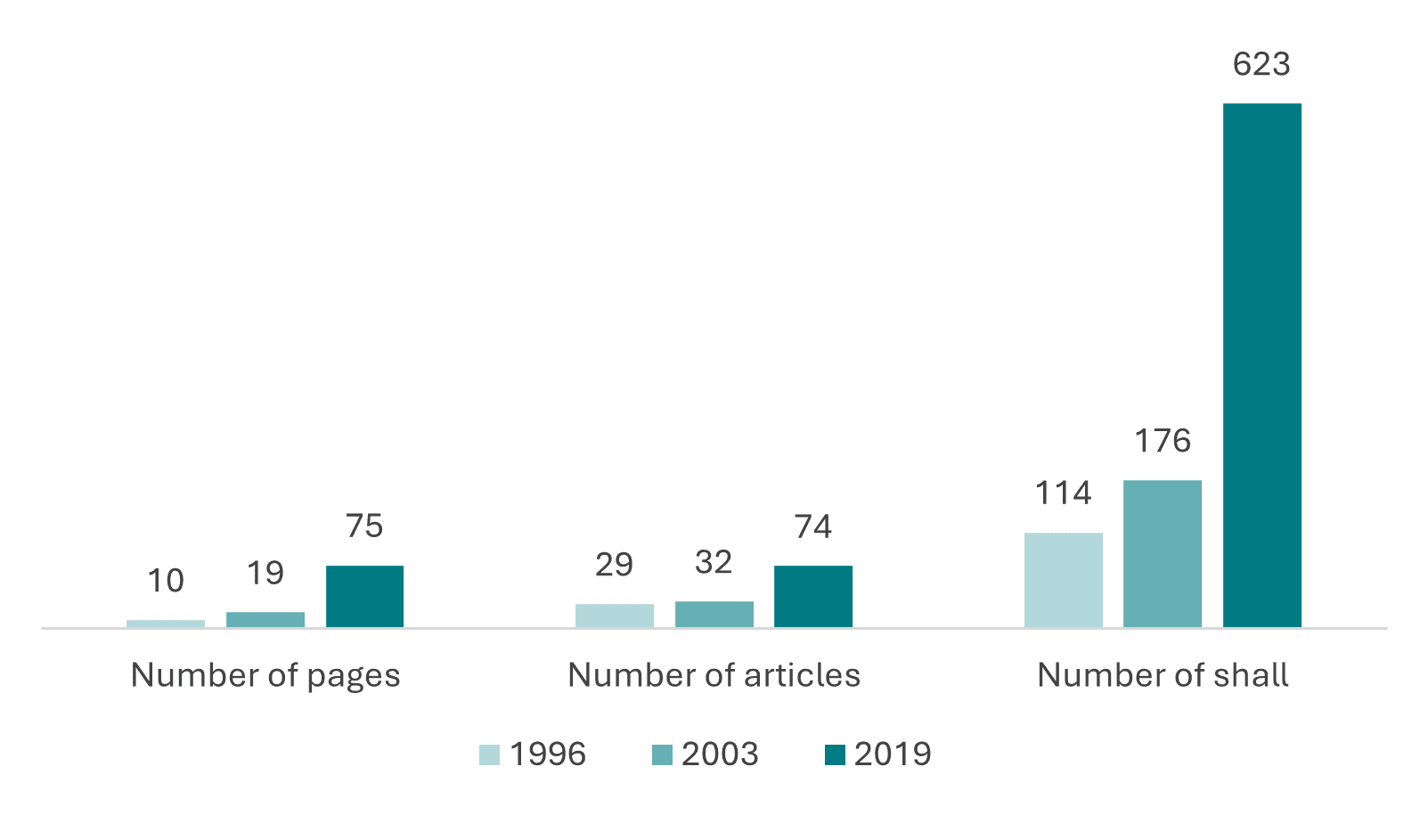

Climbing down from the peak of overregulation requires significant efforts and determination. Each iteration of EU regulation has grown increasingly complex. Consider the 1996, 2003, and 2019 versions of the Electricity Directive. Figure 1 shows that, over time, each Directive regulating the EU electricity market has become more cumbersome – with an increasing number of pages and articles – and more restrictive, as reflected by the growing number of “shall” clauses indicating obligations. True, the word shall can be used in EU legislation to prevent member states from imposing market restrictions, and as such, it can have a positive effect on competition. However, while only indicative, the figures below illustrate the increasing levels of regulatory restrictions in the EU economy.

Figure 1: Number of pages, articles and the word shall in the 1996, 2003, and 2019 Electricity Directive

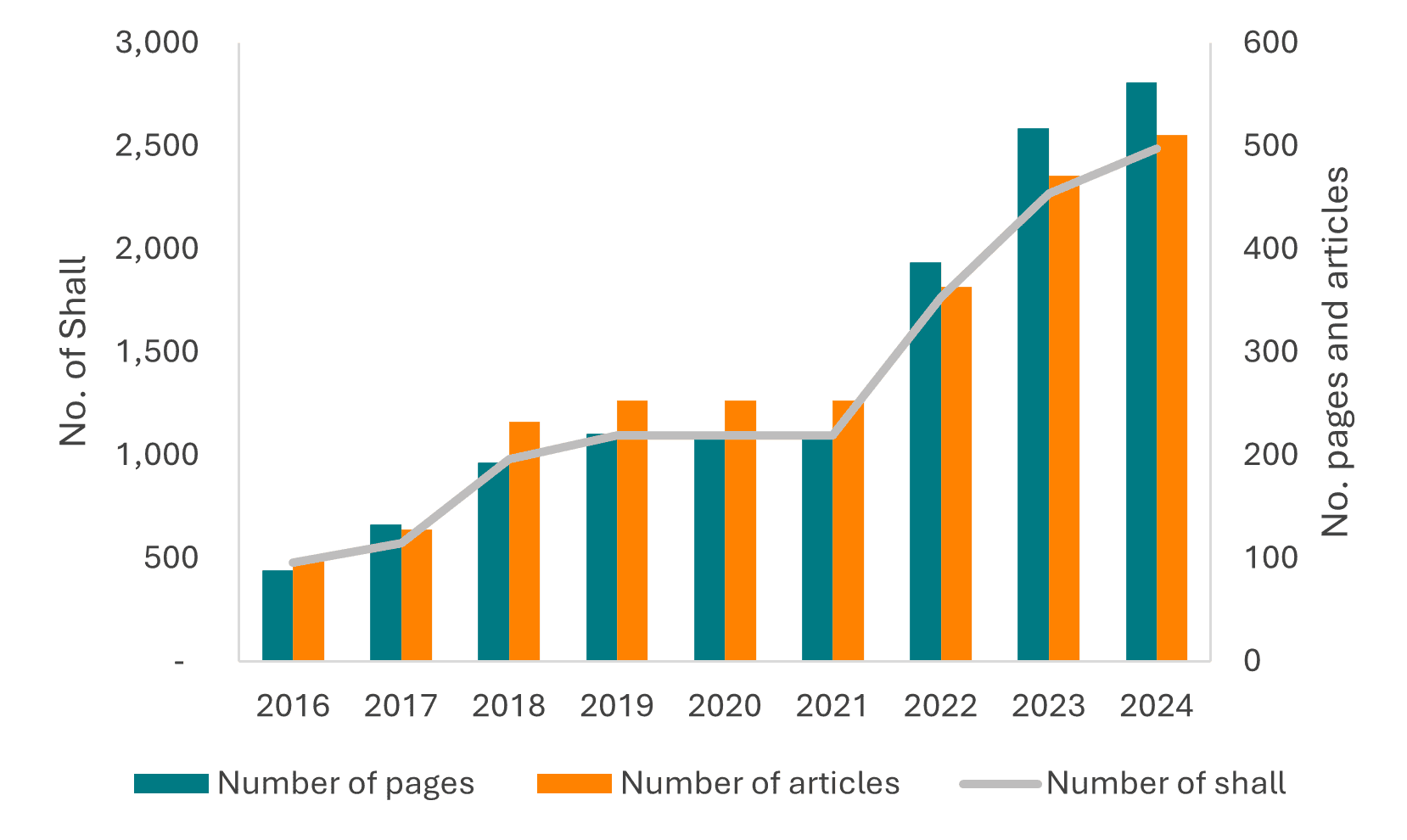

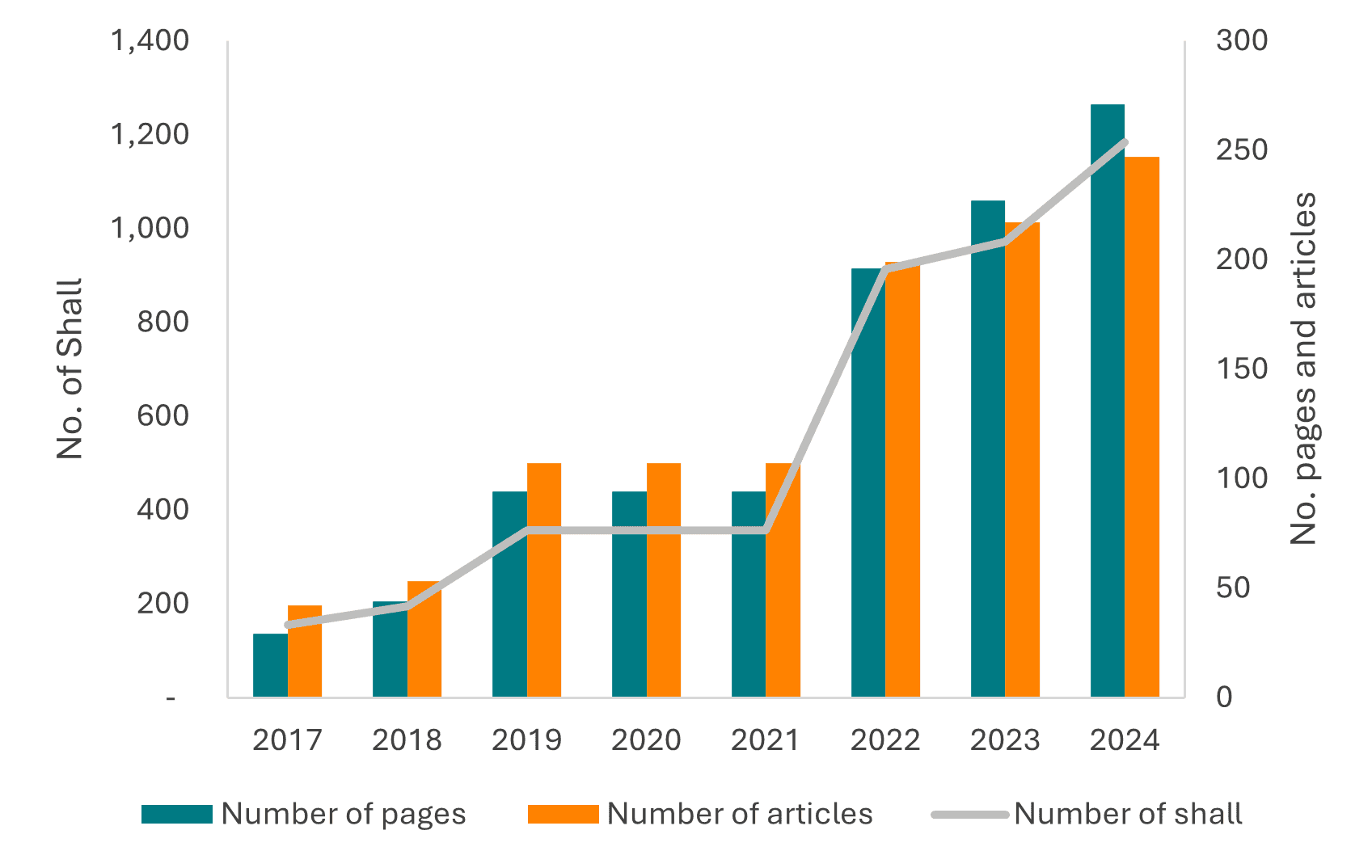

EU regulation is not only becoming more cumbersome but it is also pilling in. The amount of new regulation accumulated during the last years has been staggering. Researchers at Bruegel presented the amount of new regulation in the digital sector. Individually, each of the regulations may not represent much in terms of the administrative burden and limitations imposed on firms, but together they are a force to be reckoned with. The next two figures present the number of pages and articles (proxies for complexity) and the number of times the word shall is repeated (a proxy for restrictiveness) for two subsectors of the digital economy: Data & Privacy; and E-commerce & Consumer Protection. The data is presented cumulatively: the number of pages, articles and the word shall in one regulation is added to the pages, articles and shalls from the previous regulations.

Figure 2: Data & Privacy regulation, cumulative number of pages, articles and the word shall between 2016 and 2024

Note: The following regulations are included General Data Protection Regulation (2016); ePrivacy Directive (2017); Regulation to protect personal data processed by EU institutions, bodies offices and agencies (2018); Regulation on the free flow of non-personal data (2018); Open Data Directive (2019); Data Governance Act (2022); (Proposal) European Health Data Space (2022); European Statistics (2023); European Data Act (2023); (Proposal) Harmonisation of GDPR enforcement procedures (2023); Interoperable Europe Act (2024); Regulation on data collection for short-term rental (2024).

Figure 3: E-commerce & Consumer Protection regulation, cumulative number of pages, articles and the word shall between 2017 and 2024

Note: The following regulations are included Regulation on cooperation for the enforcement of consumer protection laws (2017); Geo-Blocking Regulation (2018); Digital content Directive (2019); Directive on certain aspects concerning contracts for the sale of goods (2019); Digital Services Act (2022); (Proposal) Right to repair Directive (2023); Political Advertising Regulation (2024).

Figures 2 and 3 speak for themselves. In less than a decade, the EU rulebook added 562 new pages and 511 new articles on Data & Privacy; as well as 271 new pages and 247 new articles on E-commerce and Consumer Protection. The number of new restrictions reached nearly 2,500 for Data & Privacy and 1,200 for E-commerce and Consumer Protection. This regulatory frenzy comes at a cost. As highlighted by former MEP, Luis Garicano, EU’s GDPR coincided with a 50 percent drop in the number of new apps. Furthermore, many of these EU regulations grow more complex when transposed into national, and in some cases, regional legislation. A study conducted by the Bank of Spain found that each additional regulatory provision was associated with a 0.7 percent decline in the employment rate of the affected sector.

Draghi’s recipe for deregulation has three ingredients: first, a vice-presidency within the European Commission dedicated to regulatory simplification; second, a new methodology to quantify the costs arising from new legislation; and third, actions to reduce the regulatory burden on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The essence of Draghi’s recommendations was reflected in the mission letters to the incoming commissioners, and Valdis Dombrovskis has been made responsible for regulatory implementation and simplification.

These proposals make sense, but we need to go further. To move away from overregulation, the EU should break free from the current group-thinking on regulation and implement the necessary safeguards to prevent costly ideas from becoming policy.

To achieve these two goals, the EU needs to outsource some of its regulatory appraisal work and the evaluation of existing regulations. There are several models to follow. The Australia Productivity Commission evaluates the costs and benefits of new regulations, conducts public inquiries into regulatory frameworks, and recommends ways to reduce unnecessary burdens. The EU can also draw inspiration from the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which provides cost estimates for new regulations, and establish a similar body to serve the European Council and the European Parliament. Importantly, the EU should take note that, unlike the European Commission’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board, the Australia Productivity Commission and the US Congressional Budget Office are independent of the executive branch.

This does not imply that the European Commission should be stripped of its resources for regulatory appraisals and evaluations. On the contrary, deregulation requires better and simpler regulation, a task that falls to regulators. The EU has a head start: EU civil servants are the most knowledgeable about which articles and provisions are used and which are not. They understand the sectors they regulate and have established channels to receive feedback from both industry and consumers. Regulators can be effective deregulators, they need sufficient resources (both human resources and time), a clear mandate, and strong leadership.