Published

Europe’s dependency on China?

By: Hosuk Lee-Makiyama Florian Forsthuber

Subjects: European Union Far-East

The 22nd EU-China Summit held virtually this week, was the first for the new EU Commission. The meeting takes place against ever-heightening tensions between Europe and China, with extremely low expectations of any outcome. Cynics were not left disappointed: The summit did not produce a joint statement, and the Chinese side even disagreed to holding a joint news conference.

The virtual summit was overshadowed by President von der Leyen’s statement on Hong Kong Security Law and China’s human rights record. Relatively strong wordings (by EU standards) that sounded like an ultimatum to the European audience, but without any tangible threats or consequences for China. It is also clear that the EU is the demandeur of a bilateral investment deal, for which the Chinese side, understandably, is expecting some form of compensation.

But the perennial China question has laid bare some considerable internal differences and ambivalence within the EU. On one side, the EU Member States compete for Chinese investments, but there are also mounting fears of how cash-rich Chinese state-backed entities might scoop up European companies and strategic assets on the cheap during a recession. This has prompted the Commission to draft new anti-subsidy tools to protect its strategic assets, conveniently prepared in time for the summit, which has understandably upset Beijing.

Brussels to also square the different internal positions on 5G security – a choice that weighs US diplomatic pressure against Chinese threats of economic retaliation. Politics aside, the EU countries have jointly identified how some high-risk 5G vendors may be vulnerable to exploitations by foreign intelligence agencies and undue state interference. On the same grounds, governments and carriers in other countries (notably Australia, New Zealand, Israel, South Korea, Japan and Vietnam) have already blocked the participation of Chinese equipment manufacturers.

Especially during the current economic downturn, where China is the first major market returning to positive GDP growth after the pandemic, overseas growth matters. The risk of retaliation weighs heavily on some of these countries who are extremely dependent on the Chinese markets.

But exactly how dependent are they on China?

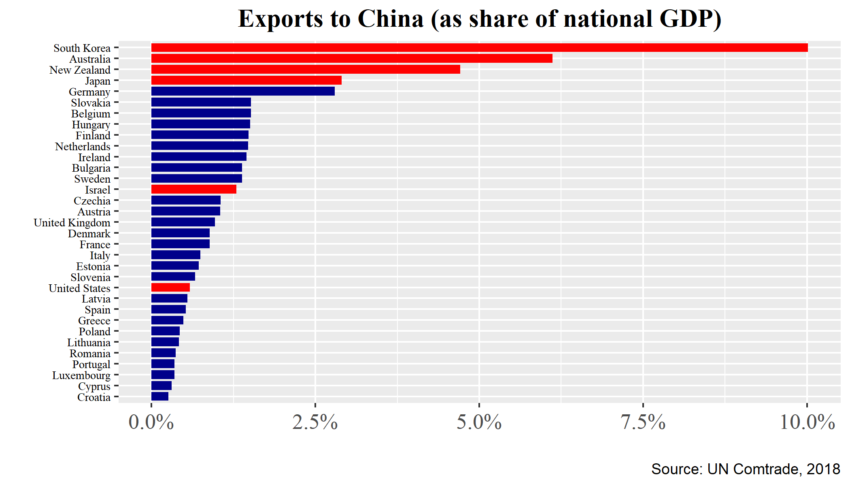

Understandably, the dependencies on the Chinese markets are naturally more pronounced for the countries in the Asia-Pacific than Europe. Despite this however, these countries have proceeded to take precautions against Chinese suppliers and 5G.

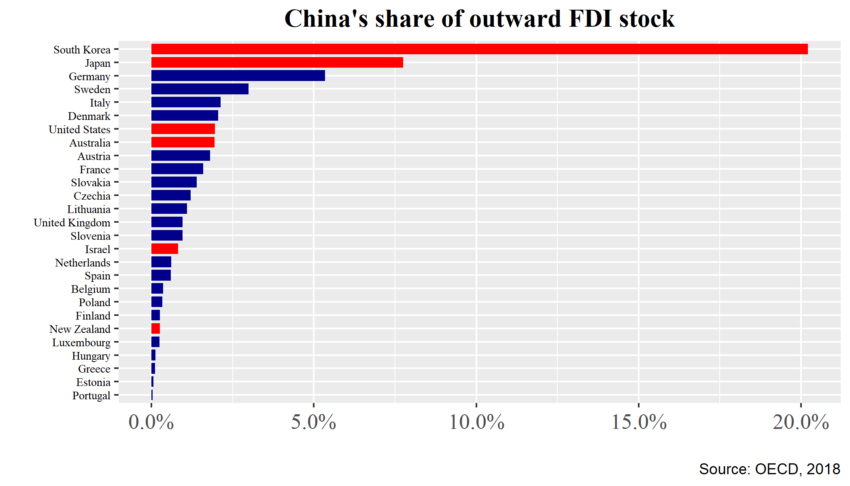

- Korea is particularly exposed, as 20% of Korean foreign direct investment (FDI) stock is invested in China, compared to 7.5% of Japanese FDI.

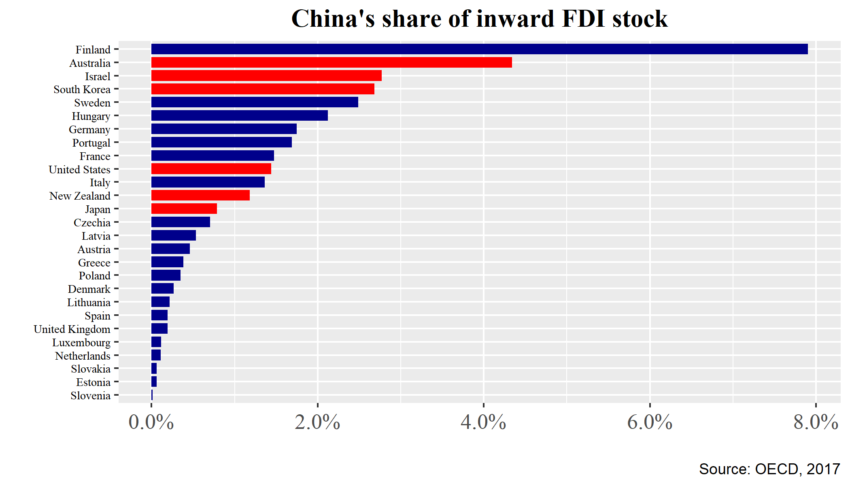

- China is also an important strategic investor in Australia, Israel and Korea.

- Furthermore, 10% of Korean GDP relies on exports to the Chinese market. The commodity-driven exports of Australia and New Zealand depend on fuelling Chinese industries and food consumption, with 6.1% and 4.7% of their GDPs respectively.

In the light of these numbers, the EU interdependencies are puny. Yet, some different positions among EU Member States concerning the treatment of Chinese investment might stem from the enormous discrepancy in involvement with China.

- At one extreme, 7.8% of Finland’s FDI stocks comes from China, whilst in Germany and France Chinese FDI accounts for less than 2%.

- Considerable differences between EU member states also persists along exports: Whilst the Chinese market amounts to close to 3% relative to GDP for Germany, the number is much lower for all other countries.

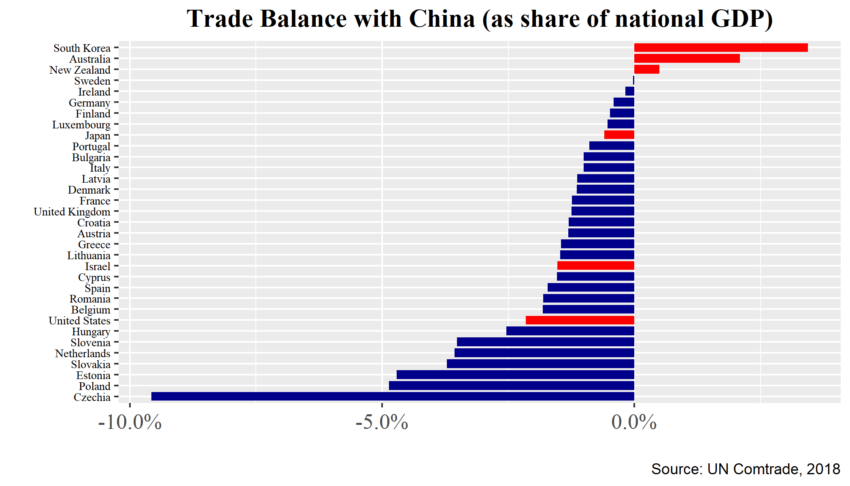

- Most notably, imports from China exceed EU exports, further stressing the point that dependency is a two-way street.

Admittedly, the graphs only provide a crude and rudimentary picture of reality. Nonetheless, dependency on China is clearly not a determinant to whether a country reverses its openness to China. Whether European countries succumb to external pressure is not determined by alliances or industrial indicators – but by the influence wielded by the domestic industries. The bottomline of telecoms and auto-makers depends on Chinese suppliers or demand. Germany may have less than 3% of its GDP (and less than zero on the balance) depending on the Chinese market – but the question is which German companies these 3% belong to.