Published

US Sanctions Against Chinese 5G: Inconsistencies and Paradoxical Outcomes

By: Hosuk Lee-Makiyama Guest Author

Subjects: Digital Economy Far-East North-America

This piece was co-authored with Robin Baker, a Research Associate at the London School of Economics.

US sanctions against Chinese 5G have been inconsistently applied for the supply of critical technologies and participation in standard-setting. Huawei may have been weakened, but the sanctions have also helped Chinese state-owned companies like ZTE and defence contractors.

1. Background

The last five years have been characterized by the geopolitical divergence of mobile communications networks. The release of Meng Wanzhou (Huawei CFO and daughter of the company’s founder) may seem like a turning point, but President Biden has generally maintained a hard line against Chinese 5G sanctions set by the Trump Administration: To date, more than thirty Chinese companies have joined Huawei and its subsidiaries on the Entity List. China’s three major mobile operators have been de-listed from the New York Stock Exchange as we take stock on the consequences of more than half a decade of bifurcation.

This analysis does not seek to challenge or evaluate the wisdom of US sanctions against Huawei (or any other Chinese entity) but takes them as a given. Rather, we look to the impact of those sanctions against market outcomes and their effects on industrial organisation. US policy on 5G aligns with a number of de facto or de jure restrictions against ‘high-risk’ vendors around the world, including Australia, the EU Member States, Japan, Korea, New Zealand. In addition, several private and state-owned operators have commercial decisions excluded 4G and 5G suppliers, factoring in the political and technical risks. Not least the Chinese state-owned operators have imposed vendor limitations by restricting the participation of European vendors. Beijing has also placed a greater emphasis on its indigenous capacity by reshoring production and consolidating supply chains.

The ex-post analysis of the 5G sanctions show that the main beneficiary of the US sanctions against Huawei has been ZTE – a Chinese self-admitted state-owned entity with military origins. ZTE has successfully evaded US Entity Listing thanks to Chinese government intervention, and also benefitting from the displacement of foreign players on the Chinese market. ZTE and other state entities are also able to participate in the ORAN Alliance, the consortium that is implicitly marketed as the alternative to Huawei.

This paradoxical conclusion shows a surprising inconsistency in selecting sanctioning targets, and the incoherence between US sanctions policy and telecom industrial policy. Needless to say, the results are highly relevant to upcoming inflection points for mobile communications networks: In recent weeks, US lawmakers led by Democratic Congresswoman Abigail Spanberger (a former CIA analyst) have called for transparency on how the US State Department has turned a blind eye to other Chinese sanctioned entities and invited them to partake in the design of US next-generation networks. The impact of existing measures should be integral to decision making as The US Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) contemplates a sanctions waiver for the ORAN Alliance and, by extension, the future course of global telecommunications standards.

2. Sanctions imposed on Chinese 5G

Figure 1: Timeline of US Sanctions under three US administrations

In 2012 – at the dawn of the 4G era – the US House Intelligence Committee released its first report raising concerns over Huawei, ZTE, other Chinese network equipment vendors and their propensity to surveil on behalf of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Since then, both firms have been de facto banned by US carriers (rather than de jure by law). Regardless, they continued to retail user devices (such as handsets, routers or tablets) to US customers, whilst also strengthening relationships with suppliers such as Intel, Microsoft and Qualcomm.

As US-China bifurcation began and the advent of 5G loomed, the Trump administration started to direct its attention to the threat of Chinese network vendors. In February 2018, FBI Director Chris Wray warned against the purchase of Huawei and ZTE mobile phones citing their apparent capacity to conduct ‘undetected espionage’. The Pentagon subsequently barred their sale on US military bases. In April 2018, state-owned ZTE was briefly re-added to BIS Entity List for selling US technology to Iran and North Korea. This prohibited American companies from engaging with the firm, until the Trump administration reached a settlement with the Chinese government and overturned the decision three months later. ZTE also paid more than $2 billion in various fines for its alleged misdemeanours.

In August 2018, the US government signed off on the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (the NDAA, or ‘McCain Act’). As well as authorising the US annual military spending, Section 889 of the bill outlined broad commitments to prohibit the federal purchase of telecommunications and video surveillance equipment from five Chinese companies: ZTE, Huawei, Hytera Communications, Hangzhou Hikvision and Dahua. Finally, in December of the same year, Huawei chief financial officer (and daughter of the company’s founder), Meng Wanzhou, was detained at Vancouver Airport for allegedly defrauding HSBC over the Huawei’s Iranian affiliate, Skycom. She was subsequently placed under house-arrest for nearly three years.

The Trump administration escalated the already ongoing policy to restrict Chinese 5G in 2016. US political appointees and diplomats calling on numerous allies to ban both Huawei and ZTE from the ongoing 5G rollout, but the US Federal Government continued to abstain from the implementation of comprehensive legislative action within the US until May 2019, when it announced its first raft of sanctions against Chinese 5G. An Executive Order declared national emergency and officially barred US companies from using telecommunications equipment produced by firms posing a ‘national security risk’. Although the EO itself did not mention specific companies, Huawei and more than sixty of its subsidiaries and business units were immediately designated to BIS Entity List for engaging in activities contrary to US security interests. The Entity Listing designation prohibits all US firms and their affiliates from supplying Huawei with goods, services and intellectual property, subject to prior approvals via Export Administration Regulations (EARs) licenses.

In effect, Huawei may neither purchase American components (such as chipsets) or license US intangibles (such as critical IPRs, virtualisation software and middleware) for use in their products, unless the supplier has received a waiver from BIS. A handful of waivers have since been granted such that Huawei may purchase limited products and participate in formally recognised standardisation development organisations (SDOs). Remarkably, state-owned ZTE (and other entities with stronger ties to Beijing) avoided being placed on the Entity List and sanctions, after the Chinese government bargained for its case. To this day, the state owned and controlled ZTE remains completely free to utilise US chipsets or R&D in their supply chains.

Despite Huawei and ZTE’s status as national security threats, there were no de jure bans on Chinese equipment in US telecoms infrastructure until mid-2019. However, in August of that year, the Trump Administration began implementing Section 889 of the NDAA with an interim rule officially banning federal agencies from purchasing equipment from the five, specified Chinese companies. In November 2019, The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) also prohibited contractors from using Federal subsidies (i.e., the Universal Service Fund) to purchase inputs from Huawei and ZTE.

2020 brought further restrictions for other Chinese technology companies. In May, BIS added another thirty-three firms to the Entity List for their alleged involvement in military activities and human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Those listed included CloudWalk Technology, FiberHome Technologies and Intellifusion.

In July 2020, the Department for Defence (DoD) announced additional measures under the blanket of Section 889. This time, Federal government contractors were banned from using equipment made by the same five, Chinese firms anywhere in their production processes. Furthermore, compliance mandated the rip and replace of existing inputs produced by prohibited companies. Retrofitting is expected to cost prospective contractors as much as $11 billion (Holland & Knight, 2020).

In August 2020, the Trump Administration published executive orders to effectively ban two, popular Chinese social media apps – TikTok and WeChat – in the interests of national security. However, with little legal standing, these orders were subsequently blocked by a US court.

Following his election defeat, President Trump signed a multitude of further executive orders against Chinese companies. In November 2020, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), under the US Treasury, imposed financial sanctions barring investment in thirty-one Chinese firms with military ties, or ‘Communist Chinese military companies’ (CMCs). On January 5, 2021, an order was issued prohibiting financial transactions within eight more Chinese software applications, including AliPay and WeChat. In a final parting shot on January 17th, the Trump Administration denied or rescinded waiver requests from Huawei’s remaining US suppliers for $119 billion worth of exports.

Since assuming office, President Biden has placed existing policy under review. EOs against Chinese software applications have been overturned, as has the declaration of a National Emergency. However, The Entity Listing decisions (against Huawei as well as the clearing of ZTE) stands firm. Any investment in alleged CMCs is still prohibited, thus China Mobile, China Telecom and China Unicom were all forced to delist from the New York Stock Exchange in May 2021. Similarly, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has recently finalized a $1.9 billion program to subsidize the “rip and replace” of Chinese equipment from federal contractors in conjunction with the upheld the application of Section 889 of the McCain Act. Moreover, the Biden administration has added another thirty Chinese companies to the Entity List (including technology firms Kindroid and Phytium who participate in the US-endorsed ORAN Alliance). The US Government has also notably tightened product restrictions on export waivers for US suppliers (Freifeld, 2021).

3. Did US sanctions change market outcomes?

Needless to say, the sanctions have had virtually no effect on the distribution of telecommunications vendors in US networks, as both Huawei and ZTE have not been used since 2012. According to the market analytics firm Dell‘Oro (2021), Huawei’s market share of radio access network (RAN) equipment in North America (including Canada) peaked at a mere 3% in 2013. By the time sanctions were imposed in 2019 it stood at less than 2%. Similarly, ZTE’s share of the North American RAN market only ever amounted to 0.2%. Hence, the limited fallout from Section 889 has landed exclusively on the very few US government contractors that had to retrofit Chinese components from Huawei and other Entity Listed suppliers.

With that said, Huawei’s designation to the Entity List has had a significant impact on its operations. By mandating export licensing requirements, BIS has constricted Huawei’s critical supply of semiconductors from US and non-US suppliers who rely on US intellectual property, including the Taiwan-based TSMC. Although cut from state-of-the-art chipsets, middleware and virtualisation software, Huawei’s footprint on the global carrier equipment markets seems to have suffered relatively little: The company even grew by 3.8% in 2020. But as chipset stockpiles have dwindled, revenues declined by nearly 30% in the first half of 2021 (Kirton, 2021). Huawei’s consumer device business – has been particularly affected. In November 2020, Huawei was forced sell its youth-focused smartphone brand, Honor, due to the ‘persistent unavailability of technical elements’ (BBC, 2020). All told, Huawei is expected to slash its smartphone output by 60% in 2021 (Kirton, 2021). Consequently, it is likely to lose its market lead in China to one, or both BBK Electronics brands, Oppo and Vivo. Elsewhere, some reports have suggested that the group is forced to sell its server division due to a heavy reliance on Intel x86 chipsets (Taiwan News, 2021).

By comparison, Huawei’s carrier business (under which RAN is organised) has proven resilient – although it is increasingly reliant on the Chinese market. In the context of ongoing bifurcation, Huawei has been de facto excluded from some network contracts in Japan, Canada and some countries in Europe and South-East Asia. As a vendor, its share of non-Chinese RAN revenue fell from 23% in 2019, to 19% in the first half of 2021 (Dell’Oro, 2021). However, these losses have been offset as Huawei continues to assemble the majority (approximately 60%) of China’s 5G network. As China currently accounts for more than 70% of the world’s 5G base stations and Huawei’s market share has only increased with the marginalisation of European vendors. The firm’s Entity List designation is also less problematic for telecommunications infrastructure, as longer product cycles demand fewer chips. The recent dip in Huawei’s carrier business revenue is reflective of a delay in China Mobile’s 700 MHz 5G tender, rather than long-term decline, why it is forecast to grow while its global share of RAN revenue has remained steady (Dell’Oro, 2021).

In contrast to Huawei, openly state-controlled entities like ZTE, Datang and Inspur have flourished under US sanctions. Their products may be banned from US government use under Section 889 – but they were merely banned from a market they were ever attempting to access in the first place. Notably ZTE has continued to evade the Entity List and is therefore free to purchase or license US technologies. In the first half of 2021, ZTE’s revenues increased by 12.4% compared with the previous year (Waring, 2021). This was largely underscored by strong growth in its consumer division. With unfettered access to US technology and reduced output from its arch-rival, Huawei, ZTE’s smartphone sales grew by 40% (Waring, 2021). The firm’s carrier division is also prospering. ZTE is responsible for approximately one third of China’s 5G rollout and has somewhat paradoxically endured less hostile exposure by the west than Huawei. With both foreign markets and domestic demand increasing, ZTE reports an increase in its global revenue by 14% and nearly $2 billion per year and doubled its profits, nearly 40% of which are generated outside China.

Ironically, the asymmetric US sanctions have weakened an (assumed) private firm in Huawei whilst strengthening a self-professed state-owned entity and a military progeny in ZTE. In particular, the US Entity Listing helped the Chinese state capital to coerce Huawei to hand over two of its business units that are now under state-led ownership. Huawei who ceded control of its Honor business to the state-owned consortium, Shenzhen Zhixin New Information Technology, as a direct consequence of its place on the Entity List. Huawei itself has been pushed closer towards China’s Central Government due to an increased dependency on the domestic market where all carriers are SOEs. It is also inevitable that the company’s founder, Ren Zhengfei, needed government support and may have been politically indebted to the CPC leadership in his campaign for his daughter’s release from Canadian custody. The selective and inconsistent targeting of US sanctions have conveyed an inadvertent message to Chinese entrepreneurs: The world is a dangerous place for Chinese entrepreneurs without government protection.

The secondary impact of US sanctions has been the marginalization of foreign vendors in China’s 5G network. Although Beijing has so far resisted in taking retaliatory measures against companies such as Microsoft and Apple, it is squeezing the likes of Ericsson and Nokia out of its ongoing 5G rollout. In 2019, only two non-Chinese firms (Ericsson and Nokia) secured around 11% of China Mobile’s ‘phase one’ tenders for more than two-hundred thousand base stations. In July 2021, non-Chinese firms secured just 6% of China Mobile’s phase two rollout. Ericsson, in particular, suffered a disproportionate reduction in its market share as a consequence of Sweden’s decision to exclude China’s extraterritorial application of its intelligence laws. In October 2021, China Mobile awarded the entirety of a smaller, third tender to Huawei and ZTE.

Finally, the current embargo on US suppliers has also accelerated Chinese-indigenous chipset developments. However, Beijing has long sought to to institute its own supply; it spent $22 billion establishing the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund already in 2014. US sanctions have only galvanized existing efforts with the Chinese government investing a further $29 billion in 2019. Beyond state funding, more than twenty-two thousand new semiconductor companies were registered in China in 2020 (SIA, 2021). These endeavours are beginning to pay dividends. China is forecast to become self-sufficient in 28nm chips by the end of 2021, and self-sufficient in 14nm chips by the end of 2022 (Baldock, 2021). Meanwhile, supply chain issues have incentivised both the EU and Japan to pursue their own strategic autonomy through government programs.

4. Implications on standards

One clearly unintentional consequence following Huawei’s designation to the Entity List is how the company and its subsidiaries are also no longer able to participate in international standardisation. However, the 5G standard depend on cross-licensing of standard-essential patents with all leading industry actors, and BIS first clarified its Export Administration Regulations (EARs) in May 2019 by issuing a temporary general licence (a decision made final in August 2020) for Huawei on standard-setting work. BIS authorized the participation of Huawei in the technical standardisation work that take place in internationally recognised standardisation organisations and the general release of intellectual property to and from Huawei provided ‘such release is made for the purpose of contributing to the revision or development of a standard in a standards organization’ (BIS, 2020). Consequently, Huawei is permitted to continue in its role as one of the leading contributors to 5G specifications in well-recognised international Standards Developing Organizations (SDOs), including 3GPP and ITU; and the standardisation work undertaken under similar rules of open and equal participation and transparency in regional SDOs such as ETSI, GSMA and TIA.

Alternatives to traditional RAN solutions have gained traction given the preponderance of five legacy suppliers – Huawei, Samsung, Nokia, ZTE and Ericsson. As an industry concept, ‘Open RAN’ proposes that at least the RAN (Radio Access Network) portion of a mobile network can be assembled by combining hardware and software components from different vendors thanks to common interfaces, virtualisation and cloud. Given that the disaggregation of traditional RAN may provide greater scope for vendor diversity, the O-RAN Alliance (an industry consortium resulting from a merger of US and Chinese groups) is defining one set of such common specifications, that is promoted by the US technology lobby with the support of several governments, including officials from the US and Japan.

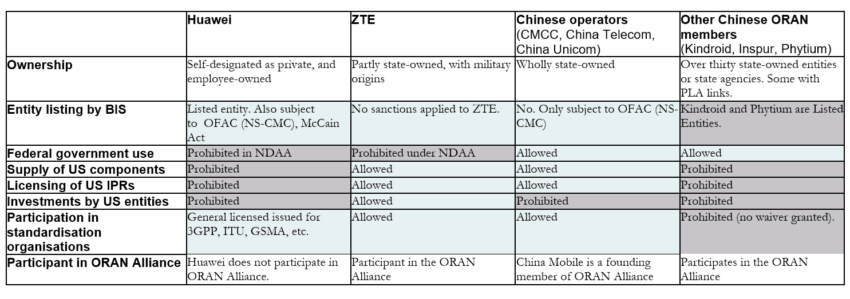

However, the O-RAN Alliance is not recognised, is not, and does not behave, like an SDO in its current form. The Alliance was founded by five incumbent mobile operators, including the state-owned China Mobile, who holds a collective veto. Other operators are permitted to join as “elected members”. But other members, including the actual manufacturers and developers of software and hardware, are labelled “contributors”. Founding members, elected members and contributors enjoy different participation rights.

The O-RAN Alliance is also fairly unique in that it develops common code in parallel to its technical specifications. Members of the O-RAN Alliance are currently jointly developing a common library of code that will run on O-RAN equipment. While the largest contributors in O-RAN are the traditional 5G vendors, even the Entity Listed companies have access to this code. By comparison, 3GPP participants make separate contributions to technical specifications to merely ensure their devices are interoperable – e.g., an Apple iPhone is able to connect to a ZTE RAN BBU unit. Under 3GPP however, 5G vendors do not jointly develop software or lines of code.

The technical specifications developed by O-RAN Alliance are also confidential and must not be disclosed until they are published by the founding five members. whereas genuine SDOs must set standards on open, transparent and on non-discriminatory basis. Entities outside of the O-RAN Alliance (including western government agencies) are only permitted to access specifications if they agree to an ‘Adopter License’ granting Alliance members, contributors and other adopters an irrevocable worldwide patent to use and distribute the licensed technology. Given its exclusive nature, its opacity and the forced licensing of intellectual property, the O-RAN Alliance does not operate as an international standards-setting organisation in the eyes of neither the US law nor the binding WTO rules, especially with regards to the TBT rules against discriminatory standards and specifications.

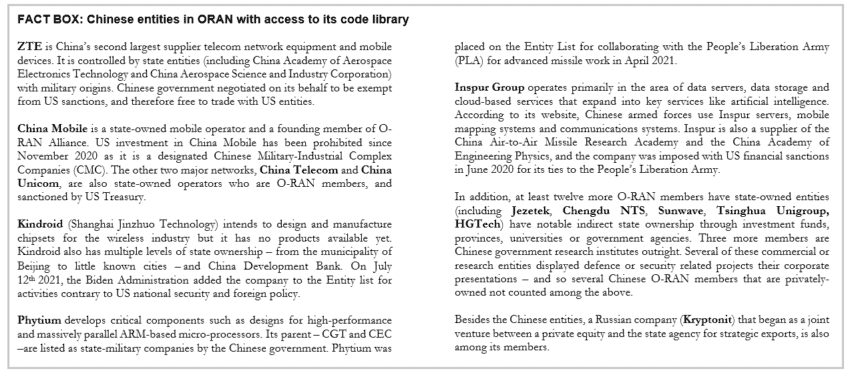

The O-RAN Alliance inarguably boasts an eclectic membership. The Alliance is comprised of two hundred and thirty-seven mobile operators and network equipment providers, forty-four of which are from China. Of these entities, three firms have been sanctioned by the US Government for their proximity to the CPC and the People’s Liberation Army. Inspur was added to the Entity List in June 2020, while both Kindroid and Phytium followed suit in 2021, Thus, sanctioned companies have been actively participating in the ORAN Alliance with considerable access to common code and other intellectual property. From this standpoint, The Alliance is effectively a forced knowledge transfer from traditional telecommunications vendors to a mix of smaller players and cloud companies. Looking ahead, some Open RAN networks may well be ‘China free’ – they will also be highly compromised due to their reliance on widely-shared technology.

5. Pending review by BIS

In September 2021, Nokia suspended its participation in the ORAN Alliance due to concerns that it (and other O-RAN members) could be in violation of US sanctions. The companies (and not least their employees who are US citizens) could incur penalties for its activities alongside Entity Listed companies. These concerns are legally correct, and BIS must ultimately decide on whether the Entity List designations are compatible with participation in SDOs or consortiums like the O-RAN Alliance. But more broadly, the inconsistencies between Huawei, ZTE and other Chinese technology companies are undeniable regardless of where one stands on the merits of these sanctions. These inconsistencies have led to a policy outcome that by and large contradicts their intended outcomes.

Looking ahead, BIS has a number of prospective options with regards to O-RAN Alliance. First, BIS could alter its Export Administration Regulations to waiver cooperation in the ORAN Alliance, as it has done for Huawei in 3GPP. To do this, BIS would have to confirm that the ORAN Alliance is an SDO, which would necessitate some fairly wholesale changes to its governance practices to be consistent with US statues and trade law, including rescinding veto powers, increasing transparency, and open membership. Ironically, Huawei could apply for membership and there would be little that the Alliance could do.

In addition to said governance reforms, BIS would have to grant a general waiver to Entity Listed members to solve the legalities of Alliance participation. As with Huawei and 3GPP, this would decriminalise licensing of IP to Phytium, Inspur and Kindroid within the bounds of an SDO. Problematically then, this solution compromises the security of O-RAN specifications as they fail to mitigate against the sharing of source code with high-risk entities. This is a unique issue in the context of the ORAN Alliance which does not occur anywhere else, as members develop a common set of code and software which will underpin critical RAN infrastructure.

As an alternative to the waiver, BIS could impose restrictions on the ORAN Alliance, mandating the exclusion of at least the OFAC and BIS sanctioned entities. The exclusion of sanctioned entities is attractive, and Kindroid has also disappeared from the O-RAN Alliance webpage. However, the state-owned (and OFAC sanctioned) China Mobile is a founding member that is unlikely to consent to such an outcome. This would effectively split the Alliance into its two, original bodies – the Chinese, “C-RAN” and the predominantly US, “xRAN Forum. A split in the Alliance would also set it back by months, if not years, and sacrifice the widely recognised benefits of interoperability and economies of scale that are necessary for O-RAN to be commercially viable.

As a third and final option, BIS could, in theory, do nothing at all. The agency is still awaiting a political appointee to be confirmed as its head, but the contradiction between efforts to curb Huawei, while indirectly sponsoring other sanctioned entities who are members of the O-RAN Alliance is not likely a tenable situation. However, status quo also fails to prevent the continued transfer of US and European know-how to sanctioned Chinese entities. Moreover, all Alliance members and their employees who are US citizens would continue to be in violation of US sanctions and expose themselves to criminal charges.

6. Conclusions: “Playing it as it lays”

Figure 2: Overview of US sanction targets

On balance, the imposition of US sanctions has amounted to double standards. Whilst Huawei links to CPC are disputed, successive administrations have applied punitive measures against Huawei that have not been applied to even more “high risk” companies with undisputable state links. Whether Huawei’s governance structure ever amounted to private ownership is almost immaterial. In China, the company is regarded as a private entity, in comparison with ZTE or Datang. Thus, the US has reinforced a public perception perpetuated by Chinese state messaging – that not even China’s most western-oriented company can survive abroad without government protection.

As a result, existing sanctions have weakened the most western-oriented (and arguably most cooperative) Chinese vendor. Its lucrative assets have been rendered worthless and sold off in a firebrand sale, into state ownership. Market data also shows that the main beneficiary of these sanctions (and marginalisation European vendors) is inarguably ZTE – a self-professed, state-owned entity with military links. To this date, ZTE remains free to purchase US chipsets, license software and access all source code developed within the ORAN Alliance.

In the long term, China has also strengthened its innovation capabilities with state funds. Whilst advances in Chinese semiconductors were probably inevitable, a shift in telecommunications standardisation was not. While the Commerce Department and Treasury, seek to marginalise the influence of Chinese and Russian state and military companies, another branch of the US government is building a drawbridge for China and Russia, inviting them into US network infrastructure that were previously free of “high-risk” vendors.

At the end of the day, the policy outcomes are binary: Either the Biden administration begin to address the inconsistencies among its sanction targets, or BIS must whitewash a policy paradox by greenlighting entities and practices that are objectively more problematic (for the US) than Huawei.

View references here

Excellent article!

The best analysis of “US shooting itself in the foot”, that I have seen for a long time.

Excellent analysis, solid empirical research work.

Would be good if US Governments had a look at this, instead of dreaming up US superpower capabilities.