Published

UK Joining the CPTPP: In Search of the Economic Benefits in Services

Subjects: UK Project

The UK has formally declared the intention to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, also known as the CPTPP trade agreement.

After Brexit, the UK government is eager to join new trade agreements, compensating for the potential losses it will face as a result of leaving the EU single market. The Pacific area is of course a dynamic region as the forces of economic gravitation are making the world economy more focused on Asia: getting a better foothold in these markets is attractive. Will it therefore also provide dynamic benefits to the UK by joining CPTPP?

From the perspective of trade economics, the answer is “probably not”. Let’s take a look at some trade numbers. These numbers will tell you nothing about the UK’s political economy, geopolitical or even geoeconomic reasons for joining the agreement: these reasons can be strong in their own right. But that’s a different matter. Trade economics will only tell where and whether there are any potential trade benefits for the UK when joining the 11-party agreement.

I take services as an example because they are the most vibrant part of the world economy and particularly important for the UK. The country has a strong comparative advantage in services and if it wants to benefit from new trade agreements, it should focus on this part of the economy. So what do numbers tell us?

For starters, gravity matters – also for services. If anybody in the UK was thinking that British firms could easily export services to far-away countries without incurring much trade costs (after all, sending a service “just requires pressing the Enter button”), then these people are wrong!

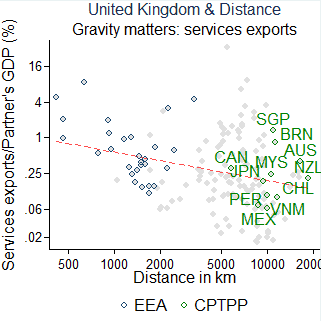

The figure shows why. It illustrates on the vertical axis the UK’s capacity to export to partner countries given their economic size. The horizontal axis plots the simple distance in km to each of the UK’s trading partners. As can be seen, trading partners far away are simply just less likely to import from the UK, even if their market is big – as can be seen by the downward sloping pink dashed line in the figure. This is a hard fact that trade economics has shown time and again.

For the UK this means that a 10 percent increase in distance reduces the capacity to trade in services by about 6 percent. Put differently, the UK may want to shift exports from, say, Athens to Ottawa (more or less a 100 percent increase in distance) but it will reduce the capacity to trade services by about 60 percent. Not because the UK trades a lot more with Greece – on the contrary, it trades a whole lot more with Canada given the country’s larger market (as measured by its GDP on the vertical axis). But that’s not the point: imports from the UK for Greece are a lot more important in its economy. Now Greece is small, but Germany, France, and the EU market altogether is not.

Moreover, many CPTPP countries are really very far away, as shown by the green dots in the figure. True, one CPTPP member is not the same trading partner for the UK as another. But here the numbers are getting even more interesting. Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, Australia, and New Zealand already show very high imports of UK services relative to their market size. Any extra exports to these countries as a result of joining CPTPP will likely only add a marginal benefit: most of what the UK is capable of shipping (or sending) to these countries is already happening.

A second group of countries is Japan and Canada. The irony here is that the UK actually trades with these countries as expected based on their relative distance and market size. Adding that extra push for more services exports was precisely done also for the UK with the help of the EU’s recently accorded trade agreements with both countries. Unless the UK is able to extract more concessions from these two countries in CPTPP than the EU has done (or what the UK has done with Japan), why otherwise bother?

Finally, the potential for UK trade becomes more interesting for the countries placed below the pink benchmark line: Mexico, Peru, Vietnam, and Chile. That is, these countries import from the UK far below their potential of what they could. But here too, some nuances need to be brought in. Already developed, Chile can scarcely be seen as a great pull factor for British services with only about 58 percent of its GDP made up of services, a meagre contrast compared to the average across for instance its OECD peers, which stands about 70 percent.

Then there is Mexico, admittedly a bigger country, but like Chile also a developed OECD country with a relatively low level of services in its economy (59 percent). Moreover, the country is unlikely to be interesting for the UK in demanding services unless the US joins the CPTPP given Mexico extremely dense supply chain network with the US.

That leaves Peru and Vietnam. Vietnam is a country that finds itself on the other side of the Pacific. It certainly is a dynamic country in the Pacific Asian region, with lots of growth potential, also in services. But the country is also greatly oriented toward China, which could turn out to be problematic for the UK. For instance, the extent to which countries are capable of trading services increasingly depends on regulations related to data. Vietnam’s model of data transfers (and processing) falls into the box of a Chinese-style approach. Hardly an example for the UK to follow.

Perhaps Peru may give some trade opportunities. Certainly, a country that will grow in the future, and will most likely develop a dynamic services sector, too. Yet, in my view a long shot for the UK to bet its hope on the country.

Sure, we don’t know how the future of services is going to evolve. Services related to Artificial Intelligence (AI) and other digital services are still in its infancy. Yet, at least at this stage membership of the CPTPP is unlikely to change the gravity effect in a dramatic way. The UK’s intention to join the CPTPP may be an interesting endeavour for reasons other than trade economics. In any event, for the UK’s services exports is hardly anything exciting.