Published

Time for a New Industrial Policy

By: Fredrik Erixon

Subjects: European Union Sectors

The European Commission is reviving industrial policy – or so we are told. A year ago it released a communication on a new industrial strategy for the EU and it is due to present an update of the strategy in the coming weeks. Last year’s strategy was a hotchpotch of ambitions and promises that have featured in most industrial strategies in the past decade, and it included the twin green and digital transitions, skills, and industrial competitiveness. It pointed to several initiatives to come in the future, including the AI strategy launched last week and the review of competition policy.

There are opportunities and problems in Europe and the global economy that motivate a stronger industrial policy. However, the direction of travel in Europe’s policy isn’t going in the right direction. There is far too little in European economic and industrial policies that addresses problems with competitiveness, and there has been a regular stream of policy initiatives from this Commission that go against the ambition of boosting Europe’s competitiveness. Recent policy proposals on corporate governance, taxonomy, and Artificial Intelligence – just to pick three – all take aim for an excessive degree of regulation that not just will burden companies with a lot more red tape but also put restrictions on new business growth in Europe.

A new industrial policy for Europe should address the core problems.

First, human capital. Europe has a big bottleneck in the supply of high-skilled labour and human capital in especially STEM areas. Shortage of labour is already a huge problem in many countries, and it’s getting worse as the labour force is nominally shrinking in countries like Germany. It’s likely to get even worse in the future as the supply of especially computer engineers and AI engineers aren’t keeping up with demand. And the consequence of an ageing workforce isn’t just impacting computer engineers. One forecast suggests Germany to have a shortage of 3 million skilled workers by 2030.

This bottleneck has a direct impact on ambitions to improve technological penetration and competitiveness in Europe’s economy. Far too many companies and sectors in Europe are distant from the global frontier of technological and innovative change, and one reason for this is skills shortages. As a consequence, potential productivity gains from new technology aren’t exploited. Especially Europe’s SME will suffer as they have greater difficulties than multinational firms to access necessary talent.

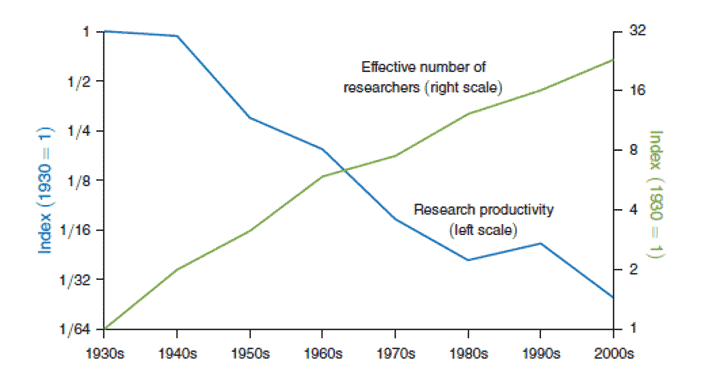

Moreover, as technological and innovation competition is growing, there is a risk that too many firms and sectors in the European economy cannot keep up pace with other advanced economies in the world. New innovation requires more labour – and this is why the cost of ideas has gone up in the economy. A group of economists calculated last year that it requires 18 times more researchers now compared with 1970 to double computer chip capacity every second year (Moore’s law). The number of researchers have gone up, but research productivity has gone down quite substantially over time (see chart 1). A growing shortage of high-skilled labour will choke innovation growth even more.

Chart 1: Aggregate evidence on research productivity Second, research excellence. The European Union doesn’t have world-leading universities. For instance, in the ranking by the Times Higher Education, the most highly ranked EU university comes at place 32nd. Over time, EU universities have fallen in these ranks and it’s bleeding obvious that they are losing their competitive edge. EU countries have many universities that are ranked in the middle, but the absence of excellence is a problem for attracting global talent and building an ecology of world-class investors and entrepreneurs around universities.

Second, research excellence. The European Union doesn’t have world-leading universities. For instance, in the ranking by the Times Higher Education, the most highly ranked EU university comes at place 32nd. Over time, EU universities have fallen in these ranks and it’s bleeding obvious that they are losing their competitive edge. EU countries have many universities that are ranked in the middle, but the absence of excellence is a problem for attracting global talent and building an ecology of world-class investors and entrepreneurs around universities.

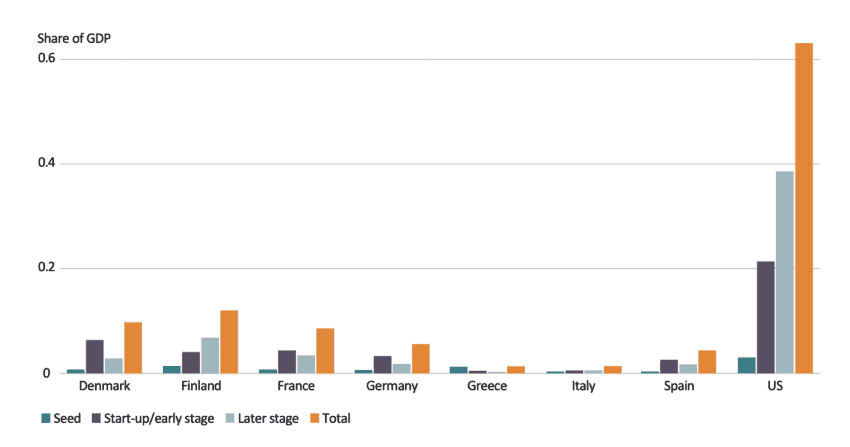

Third, funding of new business growth. Europe’s capital markets are liquid, but we struggle a lot with venture capital and finding good sources of funding for growth. There is a huge gap between the EU and the US, for instance. And that gap becomes wider in later-stage financing than in early-stage financing. Since 1995, it has been estimated that the US has invested 1.2 trillion US dollar in venture capital for startups, while the similar figure in Europe is 200 billion US dollar – a six-times difference. It is true that Europe has been catching up a bit with the US in recent years, but the gap remains stark. Moreover, the gap becomes even more significant in later-stage financing of growth (see chart 2). Europe has particularly been catching up in the financing of the growth phases of firms. In later-stages, however, Europe is far more reliant on venture capital from the US and Asia. Generally, the type of later-stage funding that is the more common route for European firms is an initial public offering – that is, to go public.

Chart 2: European and US Financing by Stage (share of GDP) While there is a case to be made for strategic investments in areas like space and defence industry, much of the new drive for a muscular industrial policy in Europe is focusing on company size and the creation of national or European champions. There’s an underlying assumption that other countries are cheating on us: Europe’s underlying problems aren’t of our own making. This is misguided. Europe’s problems with competitiveness and productivity have grown inside-out. They aren’t located among the large multinationals: they are big enough and can compete successfully. The problems stems from policies that are making it hard for SME’s to grow and keep up with technological and market changes.

While there is a case to be made for strategic investments in areas like space and defence industry, much of the new drive for a muscular industrial policy in Europe is focusing on company size and the creation of national or European champions. There’s an underlying assumption that other countries are cheating on us: Europe’s underlying problems aren’t of our own making. This is misguided. Europe’s problems with competitiveness and productivity have grown inside-out. They aren’t located among the large multinationals: they are big enough and can compete successfully. The problems stems from policies that are making it hard for SME’s to grow and keep up with technological and market changes.

In current thinking about industrial policy, far too few efforts are made and planned for solving Europe’s shortages of high-skilled labour, university excellence and venture capital. To address the problems, Europe would need to step out of the mindset of activist industrial policy and look at market barriers hindering technology diffusion and growth. Europe’s single market is full of barriers that are hindering the easy flow of technology, human capital and new business models between countries and sectors: strangely, this Commission doesn’t seem willing to do anything about them. A stronger industrial policy is called for, but it should horizontal and not aim to pick winners and give privileges to the companies that are good at making friends with policymakers.