Published

The Big Shift in Global Trade in Services: A Tale of Five Modes of Supply

By: Lucian Cernat

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union Sectors Services WTO and Globalisation

*Disclaimer: the views expressed herein are those of the author and do not represent an official position by the European Commission.

Global rules governing services trade rely on a fundamental distinction that determines how such services are traded between countries: the four modes of supply outlined in the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Yet, despite their crucial importance, modes of supply remain a rather obscure parameter for most businesses and trade experts. One reason for this neglect was the inability of statisticians to provide regular and reliable numbers on services trade, broken down by modes of supply. Fortunately, concerted effort led by the EU and other partners (UN, WTO, OECD, United States, etc.) and methodological progress at global level made this possible.

A multi-agency project initiated by DG TRADE and led by the WTO secretariat produced for the first time in 2019 a global dataset of services trade by modes of supply (TISMOS). The WTO secretariat recently released the latest update of the TISMOS database, going between 2005 and 2022, including over 200 countries. This database provides a unique opportunity to look at major events that affected global services trade in the last few years through the lens of modes of supplies.

To begin, it is perhaps useful to revisit the different modes of supplies used to deliver services internationally. A first distinction could be made between “direct” services trade and “indirect” services trade. Direct services trade are covered by the GATS agreement and can be exchanged internationally under four modes of supply:

- Mode 1: Cross-border supply – This mode typically covers digital services trade and international transport (shipping, air transport).

- Mode 2: Consumption abroad – This mode of supply primarily captures international tourism activities.

- Mode 3: Commercial Presence – Under this mode, companies establish a physical presence abroad, such as an office or subsidiary, to deliver services to foreign customers.

- Mode 4: Temporary Movement of Natural Persons – This mode refers to the temporary movement of service suppliers, or natural persons, into a foreign country to deliver a specific service. Companies utilize this mode by sending their workers abroad to perform and deliver the service in person.

Apart from these “direct” services trade, services can be traded internationally also in an “indirect” way, as part of exported goods. Think, for instance, of the software incorporated in the device (a laptop or mobile phone) you use to read this blog. Or, think of the value of the design services incorporated in the last pair of shoes you bought, in case they were imported. Such “services in boxes” are subject to GATT rules and are captured under the so-called “Mode 5” services trade.

With the key terminology defined, we are now ready to dive into the complexities of services trade. The WTO TISMOS database contains information about “direct” services trade under the four GATS modes of supply, and this is a very good starting point for our analysis.

The TISMOS data reveals a shift in the importance of various modes of supply, following the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic undeniably caused significant disruptions in international trade, including in the area of services. Existing analyses also point out the fact that different services sectors have been impacted much more negatively than others. For several years, trade in services remained below pre-Covid levels. Notably, export revenues from international tourism dropped significantly, compared to pre-Covid levels, and have not still fully recovered. Furthermore, the pandemic served as a catalyst, accelerating pre-existing technological advancements that were already significantly reshaping global trade flows. The trend towards increased reliance on digital trade has been evidently exacerbated by Covid-19.

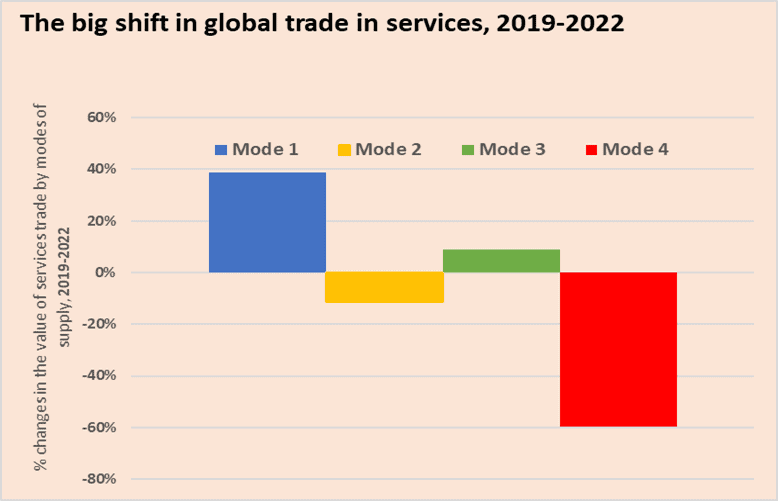

The TISMOS database provides a valuable tool to assess these interconnected trends and inform future policy priorities in the area of services trade. To capture these structural shifts accelerated by the Covid-19 pandemic, one could compare the percentage changes in the value of global services trade by modes of supply between 2019 and 2022, using the TISMOS database (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Change in trade in services by modes of supply, 2019-2022

Source: Author’s elaboration, based on the WTO TISMOS database.

Figure 1 illustrates a significant increase of nearly 40 percent in digital trade in services (Mode 1). Conversely, there has been only modest growth in Mode 3 services, which is driven by foreign direct investment (FDI) activities. In contrast, services trade reliant on the movement of people (Modes 2 and 4) has experienced a significant decline. Mode 2 services trade, primarily capturing international tourism, has decreased by an estimated 12 percent. Notably, Mode 4 services, which involve the temporary cross-border movement of service professionals, has witnessed a substantial decline of 60 percent during the same period. Unlike Mode 2, where data suggests a gradual recovery of tourism activities, the decline in Mode 4 services is likely to persist, driven in large part by a technological shift. The ability to deliver various categories of services (education, professional services, business services) through online platforms like Zoom, Skype, Teams, Webex, and others, coupled with disruptive technologies, is fundamentally reshaping the future of services trade.

Similarly, technological disruptions are also expected to affect the relevance of “indirect” Mode 5 services trade. While Mode 5 services statistics are not available in the TISMOS database, the magnitude of such services trade can be assessed from existing research and global databases, such as the WTO-OECD TIVA database. The TIVA database updates have a certain time lag and currently stops at 2020, but looking at such macroeconomic aggregates allows for a quick glimpse at the share of Mode 5 services in many OECD countries.

According to the TIVA database, the share of Mode 5 services was not significantly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic and remained relatively stable across the last few years, at around one third of the value of manufactured exports. However, even though the TIVA database indicates no fundamental macroeconomic shifts in the share of Mode 5 services, the business literature points to a pervasive digitalisation of manufacturing activities in recent years (e.g. Internet of Things, connected devices, digital twins, 3D printing, adoption of algorithms and AI technologies), which is likely to increase the contribution of services to manufacturing in the near future.

Behind this generally stable trend, there are however interesting variations across sectors and countries in the TIVA database. Motor vehicles, ICT, textiles and clothing, and metal products are some of the sectors with the highest shares of Mode 5 services in several EU countries. Among EU members, Luxembourg stands out as the EU member state with the highest share of Mode 5 in total manufactured exports at 55.7 percent. Belgium also has one of the highest Mode 5 shares in manufactured exports, at 42.5 percent. In the case of France, for instance, the value of Mode 5 services in 2020 was around 40 percent of the total value of manufactured exports, with metal products and the automotive sector having even higher values. In Sweden, the value of Mode 5 services exported by the chemical industry increased significantly over time, reaching almost 50 percent of the total value of these exports. Mode 5 services also represent more than 50 percent of the total value of ICT exports from the Netherlands.

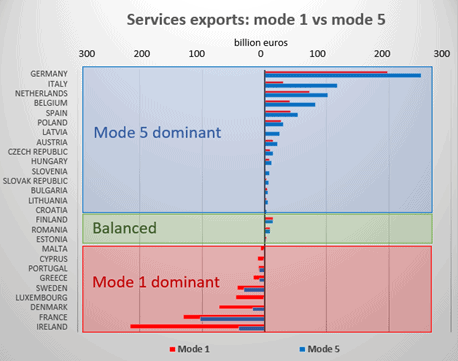

Figure 2. Mode 1 vs Mode 5 services

Source: Author’s calculations based on the TISMOS for mode 1 services and TIVA and Eurostat databases for Mode 5 services estimates. Data for 2020, the latest available year in TIVA.

Given that both Mode 1 and Mode 5 are the modes of supply most affected by recent technological changes, it is important to understand their relative intensity across EU member states. If Mode 1 and 5 are the most dynamic and technologically relevant modes of supply bound to shape the future of services trade, what additional insights can the TISMOS and TIVA database offer to policy makers? Combining the TISMOS and the TIVA data reveals a hidden fact: while all eyes are focused on “direct” digital services trade (Mode 1), for many countries “indirect” Mode 5 services turn out to be more important (Figure 2).

A first category of countries are “Mode 5-dependent”. Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium are the top countries where Mode 5 services are very significant both in absolute levels and compared to the share of Mode 1 services. For several other EU member states like Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Hungary, Mode 5 services exports are also larger than Mode 1. For these countries, Mode 5 services seem very important for industrial competitiveness. A second category of countries (Finland, Romania, Estonia) belong to a “balanced” category, whereby Mode 1 and Mode 5 services play an equal role in their trade performance. Finally, a third category of EU countries (e.g. Ireland, France, Denmark, Sweden) are “Mode 1-dependent”, i.e. Mode 1 services are bigger than Mode 5.

Understanding the relative importance of different modes of supply will be key for the global competitiveness of services sectors, and databases like TISMOS and TIVA can offer policy-relevant insights. Unfortunately, even when using such state-of-the-art global database, we are relying on data several years old to make predictions about the future. That is not ideal in our fast-paced reality. Nowadays, a few months can bring about more technological disruptions than a few past decades. For policy makers interested in the future of services trade, this data lag adds significant uncertainty for future trade policy decisions and clearly indicates the need for more recent and better services data.

Yes, despite such difficulties, TISMOS and TIVA offer some tentative policy messages that make a lot of sense. First, irrespective of which mode of supply is used predominantly to export services value-added, services will become essential ingredients for the future competitiveness of EU economies, and should be part of any reflections about industrial policy. Second, both Mode 1 and Mode 5 services have been subject to new regulatory requirements, both in Europe and abroad. Hence, the importance of regulatory cooperation to ensure that services trade do not suffer from regulatory overdrive. Last but not least, given the significant role played by both Mode 1 and Mode 5 services, it remains important to ensure that, in the future, neither of them is subject to unnecessary trade barriers. The prolongation of the customs duties moratorium obtained at the last WTO ministerial is a major boost for Mode 1 services. The “new” industrial policy debates could also consider how to also promote Mode 5 services, and to ensure that trade rules are in sync with new business and technological realities.