Published

The Right Kind of Standard to Fight a Pandemic

By: Oscar Guinea

Subjects: European Union Trade Defence WTO and Globalisation

On the 20th of March 2020, the EU made a big announcement. To help companies ramp up production on medical goods, 11 standards were made available for free. Anyone could download and read the EU technical specifications on a few medical products. The International Standard Organisation (ISO) did the same and made 28 standards on medical products free of charge.

This was mostly symbolic. The cost of buying the document that describes a standard isn’t high. Most of them cost less than $100. In the grand scheme of Covid19, free standards are not going to solve the shortage of medical goods.

And still, there were good reasons to make these standards free, gratis, and for nothing.

A standard is like a recipe, it describes the steps to make a certain good: the amounts and quality of the input and the size and technical features of the finished products. Unfortunately, this is where the analogy ends. Standards aren’t standardised. The same products must follow different standards when they are sold in Europe, US, China or Japan.

Standards can be a blockage or a bridge for international trade. Standards allow foreign companies to understand the technical requirements that a product needs to meet. Foreign firms can buy the text of the standard through the Internet, learn these specifications and adapt their products accordingly. Standards can also become a hurdle to foreign suppliers. This happens when the technical specifications are costly to implement or widely different from the specifications that foreign supplies follow to manufacture their products. Often, it depends on the kind of product. For complex products standards are mostly welcome, for simpler products not so much[1].

Standards can be national, regional (i.e. European), and international. National Standardisation Bodies can adopt the same regional or international standards to make their technical requirements equivalent or identical. For example, when two countries adopt an ISO standard, then a product can be produced for the domestic market and for sale in each other’s market. This has positive effects on trade. On average, harmonised standards increase trade flows by 0.67%[2].

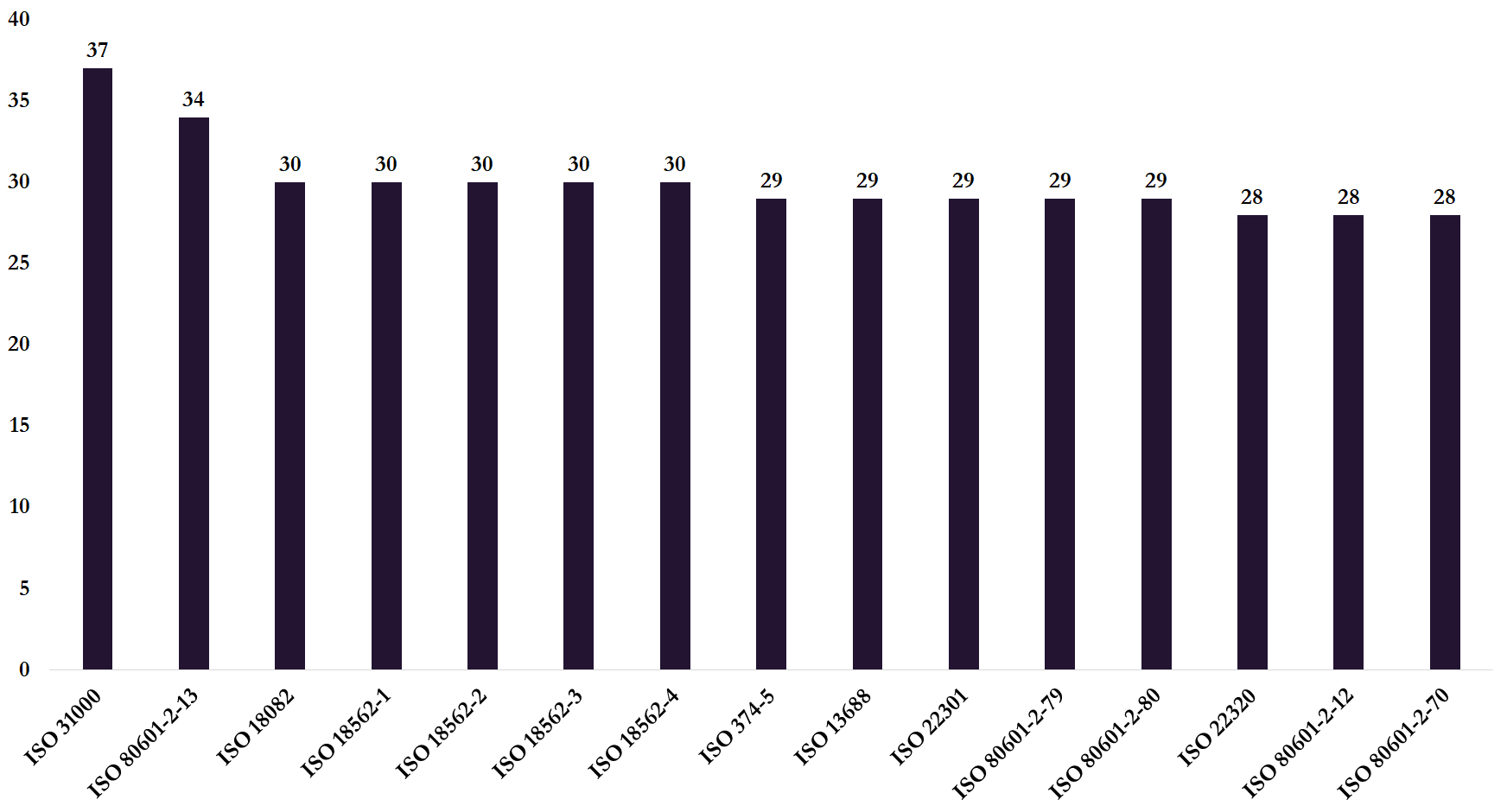

Take the standard ISO 80601-2-13. It’s an international standard for medical electrical equipment covering anaesthetic workstations and was made freely available by ISO to fight Covid19. This standard has been adopted by the European Standardisation body, and as such, it is a valid standard for all the EU countries. Besides, this standard is accepted in Brazil, Canada, Switzerland, Korea, Russia, and Turkey. The figure below shows some of the ISO standards which can be downloaded for free due to Covid19 and the number of countries where these international standards have been adopted as national standards.

Figure 1: Free ISO standards due to Covid19 and the number of countries that adopted these standards.

Source: Perinorm.

What the figure doesn’t show is that most of the standards have been adopted just by EU countries. In contrast neither US[3] nor China has adopted any of these international standards. The EU may be good at applying ISO standards but it does not matter much if other countries don’t follow these international standards too.

Lack of harmonised standards doesn’t mean that countries cannot accept goods made from abroad. As a response to Covid19, the EU and many countries around the world have lowered their trade barriers, reduced red-tape, and accepted other countries standards to get as many medical supplies as possible. (examples are here, here, and here) There have been hiccups, but overall, countries have accepted and used products made in other countries under different standards.

Make Trade Great Again

Standards and the recognition of other countries technical regulations are an important factor if countries want to be better prepared for the next crisis. The EU has put forward a notion of Open Strategic Autonomy as a way to strike a new balance between resilience and openness. However, as it stands today, it’s mostly a shallow concept with no policy initiative promoting trade.

Any initiative that facilitates trade and supports global value chains will make Europe more resilient. Unfortunately, trade policy is often wrapped in a mercantilist logic. Countries will lower their tariffs if others do the same, and countries will agree on the mutual recognition of technical regulations to gain market access. This logic is a flawed logic. There is no need for a quid pro quo. By themselves, goods and services made in other countries make us better-off.

Open Strategic Autonomy is work in progress and policymakers need to do more work to make this new concept something else than a new phrase filled with a patchwork of policies. Even a crisis like Covid19 has a certain sequence and asymmetry that allows to ramp up production in different locations. Trade makes our societies more resilient to changing circumstances and Europe’s Open Strategic Autonomy should include policies that promote trade to make the EU more resilient. A good way to start would be to support harmonised standards more broadly and the unilateral recognition of technical regulations in medical products.

[1] Moenius, J. (2004). Information versus product adaptation: The role of standards in trade. Available at SSRN 608022.

[2] Schmidt, J., & Steingress, W. (2019). No double standards: quantifying the impact of standard harmonization on trade (No. 2019-36). Bank of Canada Staff Working Paper.

[3] The US has a different institutional structure when it comes to standard settings. Mattli, W., & Büthe, T. (2003). ‘Setting international standards: technological rationality or primacy of power?’ provides a good description of how standards are set in the EU and the US.

2 responses to “The Right Kind of Standard to Fight a Pandemic”