Published

Sender-Pays: Rethinking Incentives for Infrastructure Investments

By: Hosuk Lee-Makiyama Guest Author

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union

By Robin Baker and Hosuk Lee-Makiyama

Summary

As the Sending Party Network Pays debate resurfaces, the question of whether users and senders should contribute network fees is somewhat secondary. Instead, we should be asking why our telecom operators won’t invest in their own core business without government interventions that create artificial revenue streams.

The truth is that we have created a structural problem for our telco market. As regulatory price caps and low data usage discourage local infrastructure investment, Europe’s telcos are funnelling industry cash into exorbitant dividend pay-outs and expansions in profitable markets overseas.

By failing to alter these fundamentals, ‘sender pays’ would only lead to higher dividends and further share buybacks, whilst risking diminished connectivity and retaliation from our trading partners. Heavy-handed redistribution also encourages platforms to circumvent the EU’s telcos – just as Rakuten and others have demonstrated that cloud computing, infrastructure services and network technology are converging into a common product.

Let’s begin by asking the right questions

European network operators are once again proposing that online services should fund telecoms infrastructure. Our telcos – dissatisfied with the existing regime of public subsidies and consumer payments – reason that large platforms should offer a third contribution to their assets, mostly because they are in a financial position to do so. Arguments for a Sending Party Network Pays (SPNP, or a ‘sender pays’) regime have been rehashed in an ETNO (European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association) consultancy report published in May. Unsurprisingly, the internet industry has responded in rebuttal.

The last time Europe’s telcos lobbied for sender pays, then-Commissioner Neelie Kroes issued them with some tough advice: “Adapt or die”. A decade later, many have heeded her words by integrating enterprise, streaming and cloud products into their offerings. Some have even acquired cable operators, broadcasters and content producers outright. However, the EU’s largest telcos continue to draw most of their profits from the same core business – a bit pipe that charges its users to access content from other networks.

In some ways, network operators are naturally situated in a privileged industry position. Fixed and mobile networks are publicly subsidised to varying degrees, while the majority of their R&D and standardisation work is undertaken by cloud and network equipment providers. More recently, telcos have also benefitted from the competitive prices offered by kit vendors that enjoy state aid and export credits.

Despite profitable market conditions, the EU’s largest operators claim that they cannot make a viable return on their existing outlays – much less on prospective future expenditure. This is particularly concerning given that Europe already lags behind the investment benchmark for fibre-to-the-home (FTTH) and 5G.

Although both sides of the ‘sender pays’ debate make passionate arguments, perhaps the question of whether users and senders should pay is somewhat secondary. If operators are unwilling to invest in their own core business without regulatory interventions that create new revenues, we have a much bigger problem with our telco market.

A funding issue or a structural problem?

There is little evidence of a funding issue in the telecoms industry. €130 billion of the Recovery and Resilience Facility has been earmarked for 5G and fibre deployment – which is on top of the existing support already allocated at both EU and Member State level for the next decade. Europe’s operators and investors also choose to commit €100 billion euros to telecoms projects outside of the EU (Eurostat, 2022).

In other words, European public funds are replacing cash that the private sector prefers to invest in emerging markets or the US. Whilst it is easy to blame our telcos, we should not forget that they are disincentivised from upgrading their own networks by structural impediments to local investment.

To begin, capital expenditure in Europe may not pay off. The revenues generated by EU operators are comparable to other OECD countries when measured per byte. However, the average revenue per user (ARPU) is relatively low as Europeans purchase less data than their counterparts in equivalent markets. Upgrades to local infrastructure are even less appealing in view of a regulatory regime which optimises for low consumer prices.

Aside from diminishing ARPUs, telcos’ shareholders predominantly consist of state interests, financial institutions and pension funds as a legacy of prior public ownership. Ironically, these investors have tended to prioritise steady returns over Europe’s digital future. Dividend-hungry shareholders are rarely enthusiastic about the up-front costs associated with portfolio diversification and the construction of secure, world-class networks.

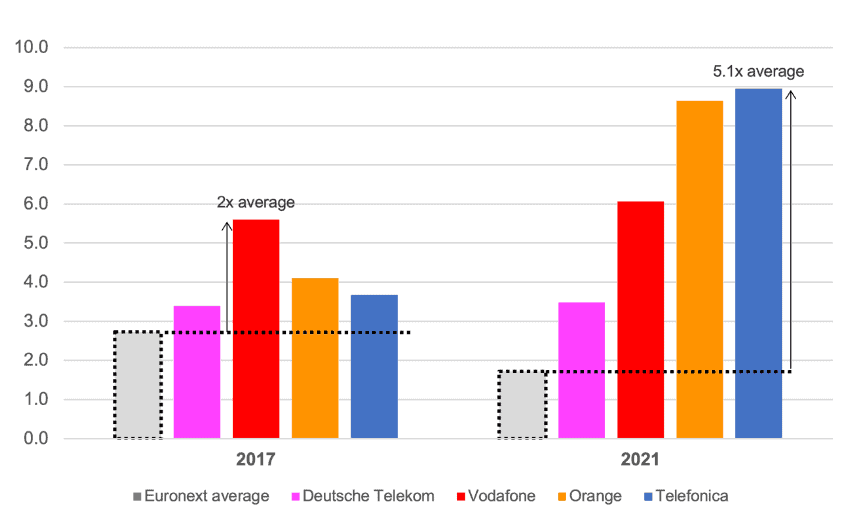

Telco dividend yields vs. Euronext average (%)

In the absence of other revenue streams, telcos’ management have few means to appease their investors and uphold the company share price. Their personal fortunes are also closely linked to market valuation via stock options. In this context, European operators exhibit a propensity to buy back their own shares and increase already-inflated dividend payments. As we see from the figure above, the EU’s largest telcos have consistently issued dividends that are well above the market average. To take an example, Vodafone has used nearly €5 billion of its own cash to buy back shares over the last five years, as well as spending at least twice that much on dividend payments (Reuters, 2021).

The logic of sending party pays

If our telcos see no logic in investing in their own business, it is hardly surprising that the industry lobbies for taxpayers, smaller operators and streaming services to foot the bill instead. The ETNO report points to a handful of online content providers, including the likes of Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, and Netflix, that account for a significant share of network traffic. Europe’s operators argue that asymmetric market capitalisation and disparities in sectoral regulation are preventing them from harnessing the revenues necessary to sufficiently contribute to Digital 2030 connectivity targets.

In this vein, telcos advocate for a means of orchestrated redistribution. Content providers may compensate operators themselves, or bypass telcos’ shareholders and make a more direct contribution to network deployment, via “a fund or form of digital taxation” (Axon, 2022).

These ideas have been tested elsewhere. Korea has implemented an SPNP regime amongst Internet Service Providers (ISPs) since 2016. This has been followed by the passing of a Content Providers’ Traffic Stabilization Law in 2020, which obliges large platforms to carry out measures that ensure a “convenient and stable” service.

Most content providers have complied with the law but there are some notable exceptions. In an ongoing court case, SK Broadband sued Netflix for the costs associated with increased traffic and maintenance work. In particular, the operator paid for the installation of a submarine cable between Korea and Netflix’s Content Delivery Network (CDN), located in Japan.

Besides the trade law and extraterritorial ramifications – where Korea collects a levy for data stored outside of its jurisdiction – we cannot preclude that the historical and commercial rivalry between Korea and Japan plays a role in the court case. After all, SK Broadband did not install a submarine cable out of altruism, but to leverage Netflix’s product as part of its own offerings.

When confronted with the notion of a sender pays regime in Europe, platforms, civil society, academics and broadcasters have made similar arguments. They note that telcos derive enormous value from content providers, with streaming services a well-recognised remedy for chronically low ARPUs. Operators themselves acknowledge the complementary nature of these products, by marketing the likes of Netflix, Spotify and Disney+ as add-ons to their own subscription packages.

‘Sender pays’ has been criticised from an antitrust perspective as well. Network usage fees would favour incumbent operators from larger economies over smaller Member States and alternative networks: SPNP shifts data centre revenues from Denmark to Germany; or from the second network to former monopolists. It also re-opens the debate on net neutrality which is established in the EU Open Internet Regulation. If a country imposes a mandatory fee or tax, telcos must assume the right to block or throttle unruly content providers. Otherwise, there would be no sanction for non-payment.

Beyond re-opening protracted debates within the EU, an SPNP regime on certain services could face a legal challenge at the World Trade Organization as a violation of the Annex on Telecom Services or the recently reinstated E-Commerce Moratorium, depending on its sectoral scope.

Finally, platforms have referenced their significant and ongoing contributions to existing network infrastructure. Tens of billions of Euros have been invested annually. This includes CDNs, hyperscale data centres and proxy servers, as well as terrestrial and submarine fibre networks. Content providers have gone to great lengths to invest in middle-mile infrastructure and deliver their services to end-users in a stable manner.

The jury – or the EU regulators – are still out on this debate. But the idea has some traction in a political climate sympathetic to platform regulation. Thierry Breton, Commissioner for the Internal Market and former CEO of France Télécom, has already voiced his support for a “reorganisation” of network remuneration (Bertuzzi, 2022). These calls have been echoed by DG for Competition and, despite pushback from MEPs and several Member States, reports suggest that the Commission is considering presenting a public consultation in the first half of 2023, followed by a regulatory proposal thereafter (Stolton, 2022).

An industry converging

In the short term, ‘sender pays’ may alleviate the symptoms of ailing industry incumbents – it could even draw hosting customers to former monopolists as data centre investments would naturally gravitate towards the largest networks. In the long term, however, the idea fails to tackle the root cause of Europe’s problem – a business environment that systemically disincentives capital expenditure at home.

The ETNO report claims that an annual ‘contribution’ of €20 billion would enable 5G network deployment with the potential to foster €36.16 billion in additional GDP by 2025 (Axon, 2022). Ignoring the back-of-the-envelope nature of these calculations, they disregard the fact that economic growth is not entirely contingent on network investment and also relies on the uptake of services, like cloud computing and other industry 4.0 applications. Forcing content providers to pay for telecoms networks without a direct commercial return effectively amounts to a punitive tax on the very digitalisation that policymakers are endeavouring to promote.

In Korea, ‘sender pays’ – like most taxes – has been associated with heightened prices. In 2021, Seoul’s transit prices were 8.3 times higher than those in Paris and 4.8 times higher than those in New York (WIK-Consult, 2022).

Market observers have also reported a decline in the diversity and quality of online content as firms try and save on network charges by relocating their CDNs. In response to ‘sender pays’, Facebook temporarily disabled its in-country cache servers increasing connection times by up to 450% (Esselaar, 2022). While Facebook has since shouldered the heightened costs, other CDN providers – that cache a rich breadth of content – have subsequently exited the Korean market.

By disincentivising data hosting, the SPNP regime has actually reduced network investment in Korea – a densely populated country with a number of inhabitants equivalent to a large Member State like Italy or Spain. Korean users have ended up paying more for an inferior service that follows an elongated traffic route. From this standpoint, a ‘sender pays’ pricing model is likely to yield commercial disputes, inflated prices and diminished connectivity rather than diverse and innovative digital ecosystems.

Aside from its threat to output, ‘sender pays’ will incentivise platforms to circumvent traditional telcos and build their own access networks. Radio Access Networks (RAN), which connect end-user devices to the core network, are increasingly software-defined, rather than hardware-based. As network functionality becomes more virtualised and less centralised, cloud computing and operator services are converging into one.

In Japan, Rakuten has already demonstrated that a major cloud player can leverage brand recognition and virtualization technologies to launch its own ‘disaggregated RAN’. Rakuten Mobile, established in April 2020, has deployed open-source software and commercial off-the-shelf components to effectively transform a hyperscale cloud into a mobile network with 97% population coverage (Morris, 2022).

The dissolution of an established internet hierarchy will unleash industrial restructuring with joint ventures, mergers and market-exits impending. Companies like AWS, Huawei and Deutsche Telekom occupy distinct positions today, but may soon offer like products and compete head-to-head.

Already, Europe’s main hyper-scale cloud providers are augmenting their centralised cloud services with multi-access edge computing. AWS Wavelength, Azure Edge and GDC Edge allow customers to run low-latency applications by offering compute and storage services at the edge of 5G networks. At the moment, these offerings are deployed in conjunction with established operators and vendors. In Berlin, for example, AWS Wavelength Zones are situated at the edge of Vodafone’s 5G network, which is built upon Nokia’s base stations.

However, heavy-handed intervention could disrupt the current commercial equilibrium. If the EU adopts ETNO’s recommendations, it would make long-term business sense for hyperscale cloud providers to even bypass the established operators via their own access networks. Platforms will meet the demand for more infrastructure investment – but on their terms, rather than compensating the EU’s telcos.

Short-sighted industrial policy risks incentivising an influx of highly innovative, US- and Chinese-owned competitors. The likes of AWS, Facebook, Huawei, Alibaba, Microsoft and Google are just an antenna away from becoming cloud-native mobile networks – and it is unlikely that they will stay in their lane forever.

Better ways of supporting EU telcos

Investment concerns over fixed and mobile networks cannot be ignored – especially in the context of sluggish rollouts. However, ‘sender pays’ risks legislative debate and diminished connectivity without addressing the underlying problem.

Instead of adding to the overall regulatory burden, the EU may consider reducing it for all telcos – and not just for incumbents. A telco must be allowed to generate a competitive profit from its own networks, rather than demanding revenues from a business customer connected to the open internet via another network.

Spectrum bandwidth auctions could be redesigned to favour prospective network investment instead of cold, hard cash. In Japan, the regulator grants radio frequency allocations by conducting a comprehensive review of operators’ plans for quality networks. If the EU were to disregard the current auction system and adopt this approach, it would incentivise telcos to improve their offerings, whilst freeing up some capital for local investment and business diversification.

Opponents may argue that auction fees are an important source of public revenue – telcos in Germany, Italy, France and Spain have spent more than €16 billion on 5G spectrum leases in the last four years. However, these numbers ultimately pale in comparison to the funding returned to the industry by the EU and its Member States.

Elsewhere, alternative operators and platforms are already constructing data centres, proxy servers and cables within Europe and cross-industry competition lies ahead. It could be a matter of time before content providers also build their own last-mile infrastructure. Alternatively, they may decide to invest in Europe’s telcos – not by paying fees or taxes, but in exchange for equity. As shareholders, it stands to reason that platforms would side with customers in prioritising well-functioning networks over inflated dividends and stock buybacks.

Either way, policymakers must encourage Europe’s operators to deliver services beyond the bit pipe. EU governments are often well-placed to do so. As direct or indirect shareholders in many incumbent telcos, they exert influence over dividend policies, management incentives and corporate strategy.

Alternatively, ETNO’s members are calling for more public funding, less competition and further leniency on co-investment agreements. From this perspective, telcos themselves appear to advocate for a return to national monopolies – where network infrastructure is deployed as a public utility that delivers to users and platforms at cost.

Conclusion

There is no denying that streaming has fundamentally changed the economics of the ‘middle-mile’ where telcos exchange their data flows (Strand Consult, 2022). To some extent, Europe resembles the US and other markets with rapid growth in online streaming, which now accounts for a major share of traffic. Yet, total network usage and operator revenues in the EU are not growing at the same rate, and the market would have already contracted without these streaming services.

It is abundantly clear that the EU has created a unique and structural problem for its telcos. Price caps and modest ARPUs contrive such that capital is funnelled towards shareholder dividends and overseas expansions. This vicious cycle does not seem to exist in any other major market.

However, ‘sender pays’ is not the answer. Regulating interconnection pricing will not deliver the investment that Europe needs. The concept fails to change structural impediments to capital expenditure and will merely lead to higher dividends and further share buybacks, as well as diminished connectivity and legal challenges. It also encourages platforms to circumvent Europe’s telcos – just as cloud computing, infrastructure services and network technology converge into a common product.

In short, ‘sender pays’ does not provide our telcos with the support they need to establish a viable market position. Instead, it reinforces their instincts to act as gatekeepers and intermediaries that deliver little value of their own.

References

Axon. (2022, May). Europe’s internet ecosystem: socioeconomic benefits of a fairer balance between tech giants and telecom operators. ETNO.

Barata, J. (2022, August 9). Joan Barata on net neutrality in Europe. CMDS.

Bertuzzi, L. (2022, May 4). Commission to make online platforms contribute to digital infrastructure. www.euractiv.com.

European 5G Observatory. (2022, April). Softbank says its 5G network now covers 90% of Japan’s population.

European Commission. (2021, December). The 2021 EU industrial R&D investment scoreboard. IRI.

European Court of Auditors. (2022). 5G roll-out in the EU: delays in deployment of networks with security issues remaining unresolved.

Esselaar, S. (2022, May 6). Doubling down and making it worse. Research ICT Solutions.

Eurostat. (2022). EU direct investment positions, breakdown by country and economic activity (BPM6). European Commission.

Lee-Makiyama, H. (2021, January). The indispensable four per cent. ECIPE.

Morris, I. (2022, May 13). Rakuten Mobile hits peak loss as it charts path to profit in 2023. Lightreading.

Reuters. (2021, July 23). Vodafone plans to launch additional share buy-back programmes this month.

Sandvine. (2022). The Global Internet Phenomena Report 2022.

Stolton, S. (2022, September 9). Breton confirms consultation on Big Tech’s telecoms contribution. Politico.

Strand Consult. (2022). Netflix v. SK Broadband. The David and Goliath Battle for Broadband Fair Cost Recovery in South Korea.

UK Investing. (2022). Dividend Yields.

WIK-Consult. (2022, February). Competitive conditions on transit and peering markets: Implications for European digital sovereignty. Bundesnetzagentur.

Williamson, B. (2022, June). An internet traffic tax would harm Europe’s digital transformation. Communications Chambers.

Williamson, B., & Howard, S. (2022, January). Thinking beyond the WACC – the investment hurdle rate and the seesaw effect. Communications Chambers.