Published

On Ants, Dinosaurs, and How to Survive a Trade Apocalypse

By: Lucian Cernat Oscar Guinea

Subjects: European Union Regions Sectors WTO and Globalisation

Palaeontologists have long recognised that unexpected but hugely devastating events can change life on Earth forever. A common theory suggests that a huge asteroid that hit the Earth around 65 million years ago in the Yucatan peninsula affected the Earth’s ecosystem in fundamental ways that led to the so-called Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event of dinosaurs and large marine reptiles, clearing the way for smaller mammals to become the dominant species on Earth. Many groups of ants were present in the previous Cretaceous era, but ants became widespread and diverse after this event.

In certain ways, the Covid-19 crisis has also shattered our world. According to various estimates, beyond its devastating health effects, the Covid-19 crisis is the most severe event affecting world trade, a trade apocalypse possibly wiping out up to one third of world trade and threatening the economic viability of potentially millions of companies engaged in trade. From the sudden eruption of a volcano to a global pandemic, it is impossible to forecast the unexpected, but we can be better prepared than the dinosaurs. Random shocks are random. The best thing we can do is to build into our systems the flexibility to cope with those shocks, learn from them, and get better afterwards.

Learning is the only positive aspect that could come out of a crisis. But to learn we need to make a concerted effort and hope that we pick up the right lessons. This crisis may be a once-in-a-lifetime event because of its global scope and symmetrical supply and demand side impact on many countries but businesses have confronted similar interruptions in the past. For example, after the 2011 earthquake, Toyota created a database on their suppliers and using that information took steps to diversify its supply chain. These efforts paid off and after the Kumamoto earthquake in 2016, Toyota recovered much faster than in 2011.

One thing we have learned during this crisis is that global value chains (GVCs) have continued working during the pandemic, delivering essential goods such as food, medicines and other necessities – including toilet paper. But it would be naïve to deny that GVCs don’t present their own risks. The Economist reported that while death rates from natural disasters have been falling, their economic cost continues to increase. In situations similar to Covid-19, firms sourcing from different locations confront an additional risk as they may need inputs originating from a potentially affected area.

While we can argue about the role of GVCs during the crisis, the unprecedented surge in demand for medical goods is undeniable. As reported by the OECD, China – which accounts for half of the world production of face masks – was unable to match its own demand and imported a large number of masks. The severity of the crisis shows that no single country produces all the goods it needs to fight this pandemic. Another OECD report calculates that for every euro of German exports of Covid-19 goods, Germany imports €0.72 of Covid-19 goods. The same for the US, for every dollar of Covid-19 good imports, the US exports $0.75 of Covid-19 goods.

Therefore, it’s important to really understand supply chains before we put forward any policy proposal to improve the current system. One important metric to have a very first idea about the vulnerability of EU supply chains, especially in terms of availability of imports (e.g. raw materials or intermediate inputs), is the number of alternative suppliers. If a certain product is imported by EU firms from a sole supplier, then that product would be more vulnerable than otherwise. Given that vulnerabilities can be of different nature (geopolitical, global, regional, etc) any assessment should take into account two levels of analysis: country-level and firm-level. If a product is supplied by a single firm, the vulnerability of EU supply chains is obvious.

Assessing the vulnerability of EU imports at firm-level is difficult, given the current lack of firm-level trade statistics. However, at the country-level, we can have a very detailed understanding of the number of countries that supply all EU’s imports. Even if a product is imported from several firms, if all the firms are located in the same region or in the same country, they can all be affected by a natural disaster (earthquake, floods) or a political dispute. Therefore, having a diversified source of imports from alternative supplying countries would increase the resilience of supply for EU firms. Otherwise, if there is a major disruption affecting this sole supplying country, EU importers would have no plan B.

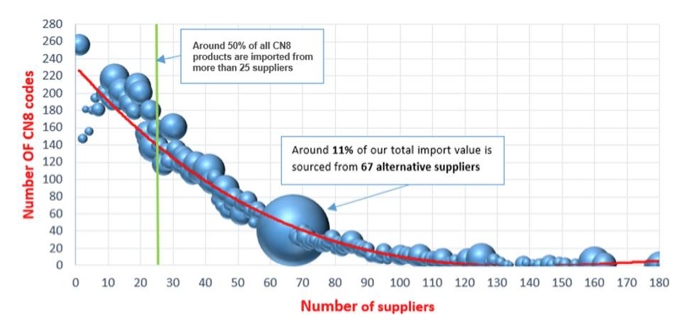

The Figure below shows EU imports of over 9,000 different products, at 8-digit level and the number of countries from where these products are imported. The size of the bubbles indicates the value of the imports. By plotting all these 9,000 imported products against the number of extra-EU27 suppliers, we can start a conversation about the vulnerability of EU supply chains.

Figure 1: EU imports and the number of extra-EU27 countries supplying these imports Source: Authors’ elaboration based on EU official import statistics at CN 8 level.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on EU official import statistics at CN 8 level.

Fortunately, most EU imported products come from more than one supplier. We can see, for instance, that one out of two products has more than 25 suppliers. But there are also a number of products for which EU importers have put all their eggs in one basket: for around 250 individual 8-digit products, the EU relies on only one source (country) of supply.

Another important metric in terms of vulnerability is the value of imports affected by such concentrated supply chains. Again, by this metric, the EU supply sources seem well diversified. The largest category of imported products (11% of total EU import values) have over 60 alternative suppliers. And if we look at the most vulnerable products where the EU has a sole supplier, the value of trade affected is less than 1% of total EU imports.

Trade value alone, however, is not sufficient to assess vulnerability. When the Icelandic volcano eruption blocked the supply of airbag sensors from a small Irish supplier to Japanese car plants in Asia, the lack of a small value component stopped the production of entire cars. Therefore, one should not jump to conclusions based on one simple metric to assess a complex GVC reality. Each of these 9,000 products is imported by many EU firms. And individual firms may be more exposed to sole suppliers. Even though systematic firm-level data on export and import patterns for each of these 9,000 products is not available at the EU level, the few Eurostat indicators on trade at firm level indicate that a majority of EU member states (e.g. ranging from Spain, France, Netherlands, Italy to Romania, Sweden and Estonia) have more than 50% of their importers (essentially SMEs) reliant on a single supplying country (Eurostat, TEC data).

So, at the country level, supply chain vulnerabilities seem to be more product-specific, rather than ubiquitous. While at firm-level, we may find that many firms may be more exposed to such vulnerabilities from concentrated supply chains. Then, how can we build a more resilient and robust trading system? For example, having several suppliers in multiple locations is a strategy for robustness. Having compatible standards boosts resilience by having a stock of standardised inputs that are easier to replace, and by facilitating the reconversion of other firms towards critical products in short supply.

In essence, extreme dependence on one supplier can make the supply network vulnerable. But just like the Cretaceous apocalypse, a trading system that is made of many (smaller) firms is more resilient and robust in its entirety than one based on fewer suppliers ‑ regardless of them being domestic or foreign. Faced with a random shock like Covid-19, a system that relies on a handful of large suppliers is more exposed to those suppliers closing their factories or been unable to produce than a system based on numerous (smaller) firms in multiple locations. For instance, a March 2000 fire at the Philips manufacturing plant in New Mexico, impacted supplies of radio-frequency chips to several other downstream producers. Those who had access to more diversified suppliers were able to recover more quickly. Similarly, when exports are concentrated on a few large companies, trade becomes more vulnerable to shocks hitting these large players in international markets.

This points to the importance of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in ensuring a diversified and more resilient trading structure. Like ants, they are individually more vulnerable than larger firms and the current crisis points to their acute vulnerabilities. However, unlike dinosaurs when an asteroid hit our planet, SMEs are geographically dispersed and regarding their systemic exposure, more diversified in terms of suppliers, sourcing and products. If one ant disappears, there are many others still in business. If a large firm is hit by a global catastrophe and that firm accounts for a large share of trade, the shock may be irreparable. Which is another reason to work towards a systematic Trade Policy 2.0 approach to build an evidence-based monitoring platform of EU trade policy.

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not reflect an official position of the European Commission.

5 responses to “On Ants, Dinosaurs, and How to Survive a Trade Apocalypse”