Published

Europe’s Economic Security in Services

By: Oscar Guinea Vanika Sharma

Subjects: European Union Services

Economic security reached the Mount Olympus of European buzzwords when Maroš Šefčovič was appointed EU Commissioner for Trade and Economic Security. However, Europe’s concern over its economic security has been going on for some time. Already during von der Leyen’s first Commission, the EU approved a series of policies, such as the Critical Raw Material Act, the Anti-Coercion Instrument, the European Chips Act, and the Net-Zero Industry Act to strengthen its economic security. And more is to come if one reads the Competitiveness Compass whose third pillar outlines a saga of trade agreements, investment partnerships, joint purchasing programmes, strategies, directives and regulations to guarantee Europe’s economic security.

Most of these policies – and the metrics to measure EU’s vulnerabilities – concern trade in goods. But what about Europe’s economic security in services? Does Europe suffer from dependencies in services that can be used to its disadvantage? And should trade in services be a part of Europe’s economic security agenda?

The Starting Point: Measuring Trade Dependencies in Services

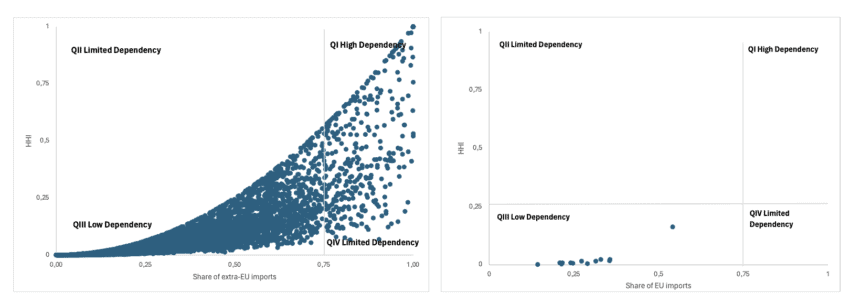

Coercion and economic harm from trade can arise when there are trade dependencies for the provision of certain goods that can be exploited by the exporting country. In an earlier ECIPE study we developed a conceptual framework to measure Europe’s trade dependencies. Using this framework, the EU faced import dependencies in 282 product categories, with a value of USD 58.5 billion. Meanwhile, for trade in services (for aggregated sectors), the EU had no import dependencies.

Figure 1: EU import dependencies in goods (left) and services (right) Source: Author’s calculations, UNComtrade

Source: Author’s calculations, UNComtrade

Securing Economic Security for Services: Building an EU model

A lack of economic dependencies in services does not mean that the EU can overlook its economic security in services. Services trade is a key channel through which technologies that are critical for national security such as advanced mobile communication, AI, quantum computing, and edge and hybrid computing are exchanged and diffused. Therefore, Europe’s approach to economic security in services should be different than that for goods.

The EU is the world’s largest exporter and importer of services, accounting for a quarter of global exports and imports while enjoying a trade surplus of €163 billion. Behind these figures are large, medium, and small service companies, many of which operate at the technological frontier. Take the EU’s information and communication technology (ICT) sector as an example. Unlike the US and China, whose ICT sector is dominated by large companies and conglomerates, the EU’s ICT sector is primarily composed of small and medium enterprises (SMEs made up 96 per cent of the 1.2 million firms in the sector in 2022). Despite not having large champions, the EU’s ICT sector is highly competitive in ICT services trade, investment in R&D, and global standard-setting.

Therefore, a strategy for the EU’s economic security for services demands policies that are less defensive and more offensive. It requires policies to maintain Europe’s competitive advantage rather than developing policy instruments that address these challenges ex-post. This calls for supply-side measures and a horizontal industrial policy that focuses on productivity, innovation, and economic growth rather than targeting specific sectors.

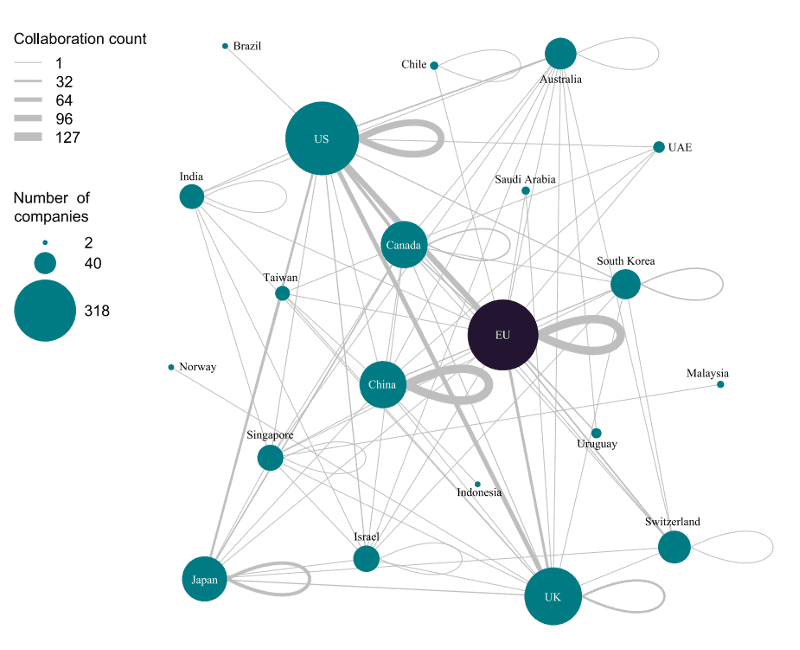

The development of quantum technology in the EU offers a great example of the importance of horizontal policies. There is no question about the critical role of quantum technologies in Europe’s prosperity and national security. Quantum technologies have the potential to transform economic sectors where EU companies are global leaders such as aerospace, automotives, pharmaceuticals, and finance. However, in the development and diffusion of quantum technologies, partnerships between EU companies and non-EU firms are more important than partnerships among EU companies. This can be seen in Figure 2 which illustrates the number of collaborations among EU companies and between EU and non-EU firms. 63 percent of all EU partnerships in quantum technologies were between an EU and a non-EU company, while 37 percent were between EU companies. Openness, rather than autonomy or sovereignty, is the best policy recipe for the development of quantum technologies in the EU.

Figure 2: Network of quantum technology collaborations

Conclusion

Europe does not face the same problem of economic dependency in services as it does for certain goods. However, given the growing role of services in pushing the technology frontier, there are compelling reasons to consider economic security in the services sector. However, it requires a different approach compared to that used for goods.

To strengthen its economic security in services, the EU must foster companies that can lead in the technologies of tomorrow. Fortunately, the EU possesses a vibrant and diverse ecosystem of services companies, high levels of human capital, and a market economy underpinned by strong institutions, the rule of law, and robust intellectual property protections. These factors are Europe’s comparative advantages.

Ultimately, the goal of any EU strategy for economic security in services should be to create the conditions for European services companies to deliver cutting-edge products. This requires the right economic fundamentals such as access to foreign and domestic technology and human capital and the right conditions to make R&D investments rather than a new wave of regulations.