Regulating the Working Conditions of Platform Work: What Can We Learn from EU Member States?

Published By: Oscar Guinea Elena Sisto Oscar du Roy

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union Services

Summary

Policymakers in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain share the common objective of enhancing the working conditions of platform workers. However, variations in their labour markets, legal frameworks, and political landscapes have led to four distinct approaches in achieving this goal. Predominantly, the Spanish regulation has been geared towards attempting to reclassify platform workers from self-employed to employees. In contrast, the regulatory strategies in France and Greece have focused on retaining the sector within the realm of independent work, while simultaneously improving the working conditions of platform workers. Estonia adopted a broader perspective, emphasising the enhancement of working conditions for all freelancers, not exclusively those categorised as platform workers.

This Policy Brief offers a comprehensive evaluation and comparison of the regulatory frameworks governing platform work in four European countries. The comparative analysis draws upon research conducted by the OECD and the World Economic Forum (WEF) on the principles of good regulation. Adapting this research to the context of digital platforms, three key principles for assessing the regulation of working conditions on these platforms were identified: (i) the consistency with the policy objective of improving the working conditions of platform workers; (ii) the feasibility of implementing the regulatory requirements; (iii) the presence of regulatory dialogue and appeal mechanisms.

The evaluation of the four countries’ regulations against the three outlined principles offers valuable insights into the regulation of platform work.

In Spain, the primary aim of the regulation regarding platform workers was not solely the improvement of working conditions but predominantly the reclassification of platform workers from self-employed to employees. This distinction is crucial, as platform workers highly value the benefits of self-employment, such as access to work, income opportunities, flexibility, and autonomy. Evidence presented in this study suggests that a majority of Spanish delivery workers preferred to maintain their self-employed status, while only about one-third expressed a desire to be classified as employees. Moreover, the Spanish regulation is characterised by a broad formulation of the conditions defining employment for digital delivery workers. This lack of specificity has led to an uncertain application of the regulation, with digital platforms adopting diverse strategies to achieve compliance. Ultimately, the Spanish regulatory framework has been marred by a profound disregard for the interests of, and a notable lack of communication with, those directly impacted by the regulation: the digital platforms and the platform workers.

Greece has demonstrated that it is possible to enhance working conditions for platform workers while preserving the advantages of self-employment. The Greek regulation mandates that digital platforms adhere to the same welfare, health, and safety obligations for platform workers as they would for employees. Additionally, Greece has established clear criteria to define the presumption of self-employment for platform workers. This clarity offers legal certainty and enabled platform workers to accurately assess their employment status. Consequently, there has been a notable reduction in court cases regarding the classification of platform workers.

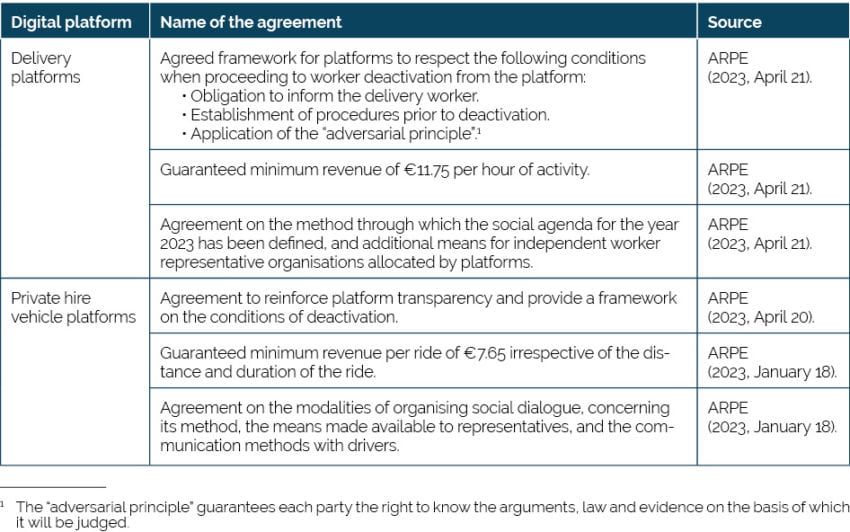

France has progressively developed a comprehensive legal framework that has systematically enhanced the rights of platform workers. This development culminated in six pivotal agreements, addressing some of the most challenging aspects of working conditions on digital platforms, such as account deactivation and minimum revenue. These agreements were reached under the auspices of the Autorité des Relations Sociales des Plateformes d’Emploi (ARPE), a public entity instrumental in facilitating effective social dialogue between digital platforms and trade unions. The establishment of clear administrative procedures governing the negotiations within ARPE has been crucial in formulating measures that digital platforms can effectively implement.

Estonia’s primary focus is on ensuring adequate working conditions for all freelancers, including platform workers. A considerable number of platform workers in Estonia engage in a contract-for-services (töövõtuleping) with digital platforms. This contract offers a social safety net, including unemployment benefits, sick pay, and healthcare services, while retaining the self-employed status of platform workers. Moreover, this framework provides clarity regarding the rights and responsibilities of both platform workers and digital platforms, facilitating the implementation of a clear and unambiguous regulatory system.

This comparative analysis enabled the formulation of four policy-recommendations for policymakers interested in the regulation of working conditions for platform workers:

- Harness the benefits of digital platforms for platform workers

Digital platforms provide workers with significant advantages, including access to work, income opportunities, flexibility, and autonomy. These advantages play a crucial role in influencing platform workers’ decisions to offer their services via digital platforms. Therefore, it is essential for policymakers to focus on preserving these benefits when formulating regulatory frameworks that govern working conditions on digital platforms.

- Improve the working conditions for platform workers independently of their employment status

The experiences of Greece, France, and Estonia demonstrate that it is entirely feasible to acknowledge the unique circumstances of platform workers, affording them additional rights, while preserving their self-employed status and the associated benefits of this form of employment. Evidence supports the preference of platform workers for this arrangement. For instance, four out of five couriers would consider ceasing their work if legislation compelled them into traditional employment lacking flexibility.

- Establish clear employment status criteria

In countries with legal frameworks that differentiate between types of workers, the issue of employment status often requires careful consideration. Greece has incorporated into its legislation four clear conditions that must be met for a platform worker to be classified as self-employed. In contrast, the Spanish legislation employs a rebuttable presumption of employment under vague conditions. The outcomes of these two legislative approaches are markedly different. In Greece, the clarity provided by the explicit criteria has led to a significant decrease in the number of court cases related to reclassification. On the other hand, Spain continues to grapple with legal uncertainty and a diverse application of its regulatory framework.

- Empower platform workers’ representation

Hearing the voices of platform workers and addressing their concerns in the regulatory process is essential to effectively regulate their working conditions. Given the unique structure of the platform work sector, this is not an easy task. However, the approach adopted by France, as well as recent developments in the European Commission Guidelines on collective bargaining, offer practical examples of how the interests of digital platform workers can be effectively integrated into social dialogue.

This Policy Brief was commissioned and funded by Delivery Platforms Europe.

1. Introduction

Digital technologies have introduced new methods for matching labour supply and demand. However, the regulations governing labour markets were established long before the advent of digital platforms. The interaction between these emerging technologies and the established rules presents a significant challenge to policymakers. They are tasked with finding ways to ensure that platform workers receive adequate protection, while simultaneously preserving the benefits that digital technologies provide.

This task is far from straightforward. Firstly, digital platforms and the workers they engage are highly diverse, and the tasks executed through these platforms differ markedly from ‘traditional’ work norms. Self-employed platform workers typically receive compensation on a per-task basis, rather than a conventional hourly wage. Additionally, for the majority of platform workers, income from this work is supplementary, not constituting their primary source of earnings. Secondly, the nature of platform work, often involving engagement with multiple competing platforms. This aspect makes it particularly difficult to delineate working time among different platforms.

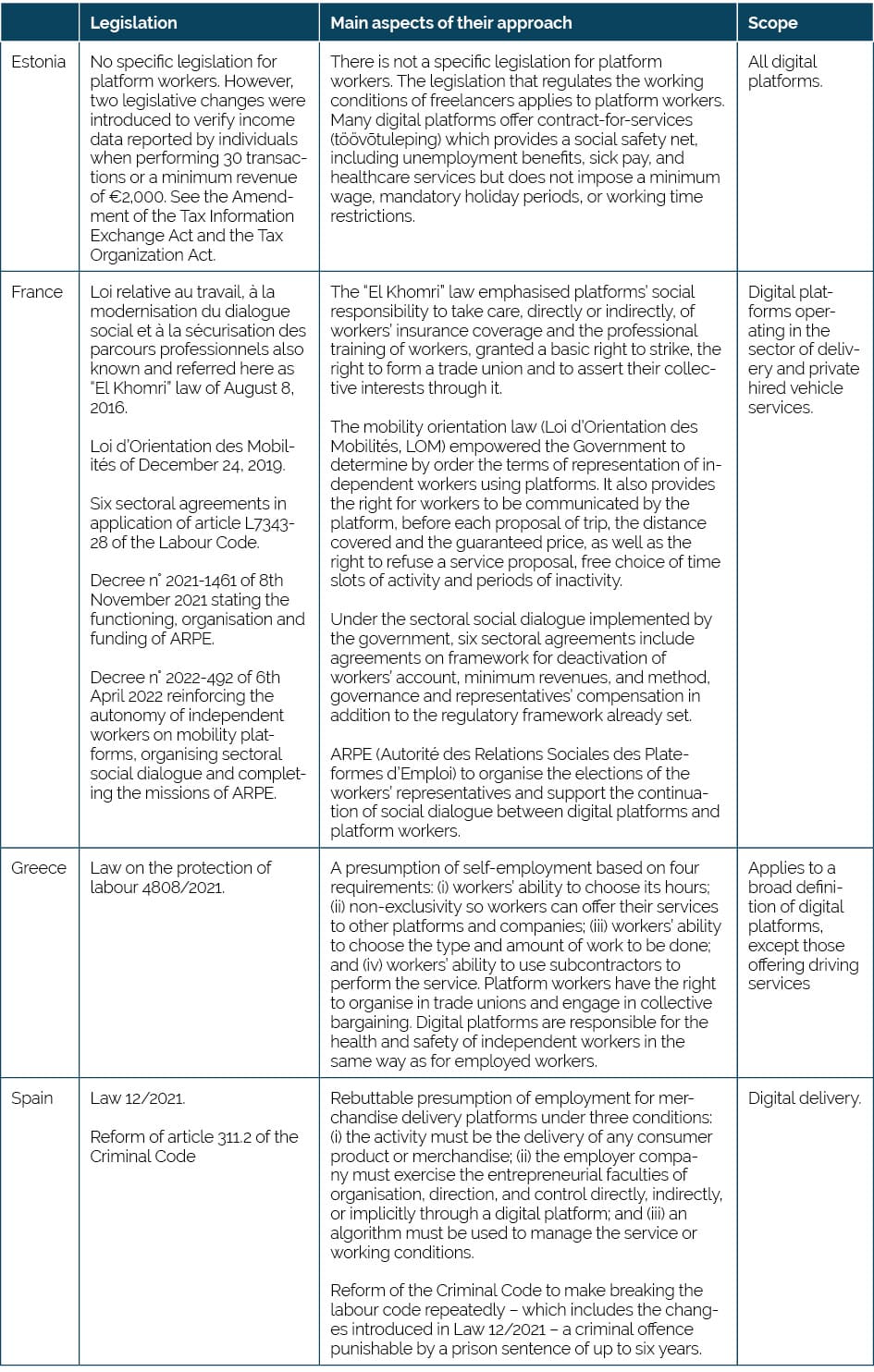

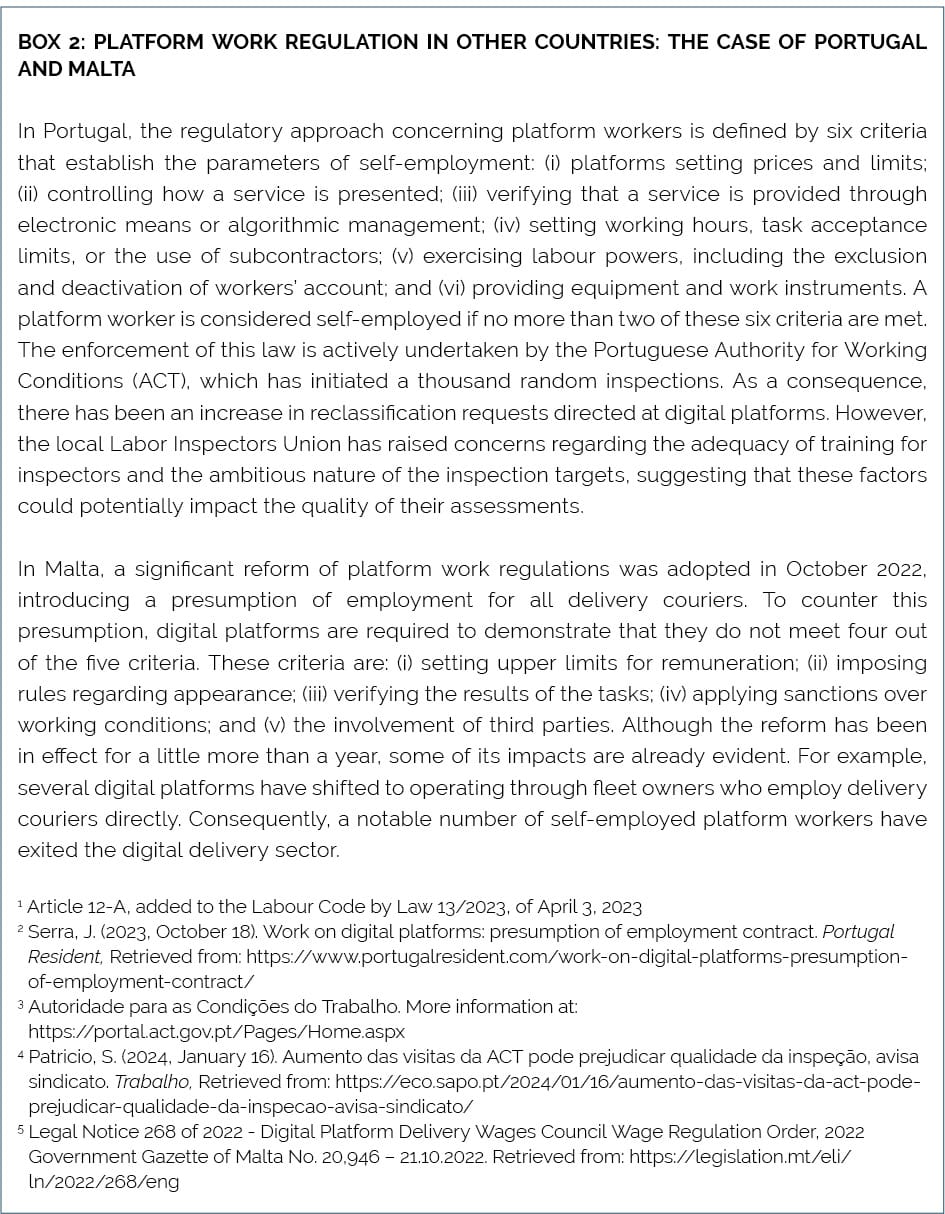

Within the EU, several member states have taken steps to regulate various aspects of working conditions on digital platforms[1]. This Policy Brief conducts a comparative analysis of the approaches adopted by Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain. These four countries have been selected due to their diverse regulatory approaches, reflecting the unique characteristics of their respective labour markets and the policy choices made by each government. A table is provided below to offer an overview of the legislation in each of these countries as it pertains to the working conditions on digital platforms.

Regulatory approaches in Spain and Greece primarily revolve around the employment status of platform workers, focusing on whether they should be classified as employees or self-employed individuals. In Greece, self-employment is distinctly defined by four specific criteria. In contrast, Spanish legislation operates on the assumption that digital platforms exercise control over platform workers, resulting in a general, though rebuttable[2], presumption of employment. In France, the emphasis is placed on establishing an institutional framework that supports dialogue between digital platforms and platform workers, with the objective of enhancing labour conditions of platform workers. Conversely, in Estonia, the government’s goal extends beyond platform work, aiming to improve the working conditions for all freelance workers, including those engaged on digital platforms.

Table 1: Digital platform work regulation in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain

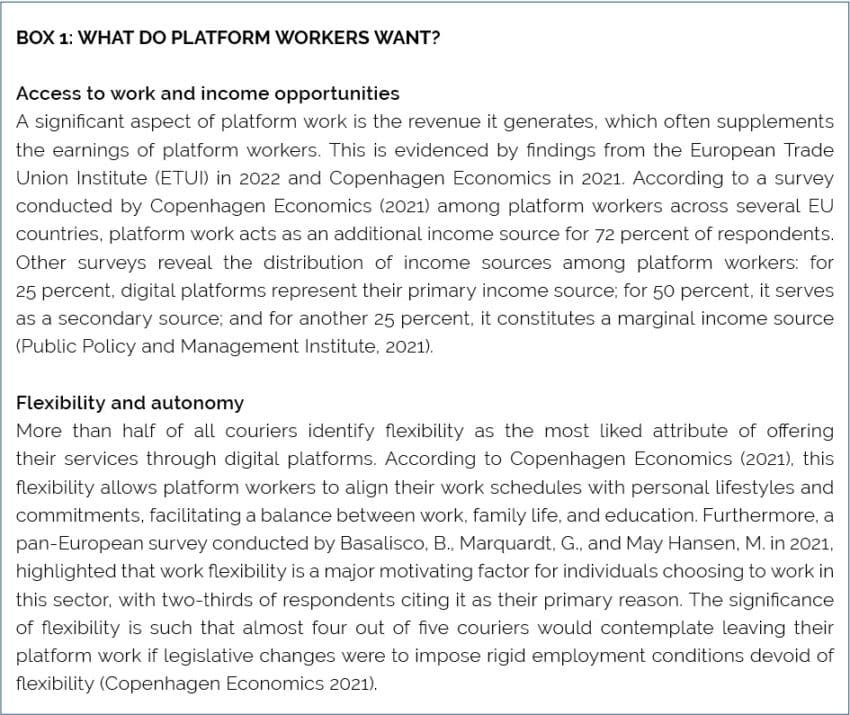

This Policy Brief operates under the assumption that a straightforward yet fundamental objective is shared in the regulations of the four countries: the improvement of working conditions for platform workers. In pursuit of this goal, it is crucial that policymakers pay close attention to the voices of platform workers themselves. The needs and preferences of platform workers are clearly reflected in surveys conducted across the EU (see Box 1). The collected evidence indicates that platform workers desire an adequate level of protection while retaining the benefits derived from digital platforms. These benefits include access to work, income opportunities, flexibility and autonomy.

The analysis presented in this study is of critical importance for countries exploring ways to regulate the working conditions on digital platforms. It is essential that any regulatory framework concerning platform work is grounded in well-established principles of good regulation, steering clear of vague criteria that could hinder the implementation and enforcement of new policies. Fortunately, international organisations have developed a substantial body of work to assist countries in designing and implementing effective and efficient regulatory policies.

Our methodology, outlined in Chapter Two, draws upon this extensive body of work and identifies three primary principles of good regulation applicable to the regulation of working conditions on digital platforms. Chapter Three evaluates the regulatory frameworks in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain, measuring them against these principles. The objective is to discern what works and identify areas requiring improvement to adequately address the needs of platform workers. Building upon this analysis, Chapter Four presents a series of policy recommendations designed to guide policymakers in maximising the benefits that digital platforms offer to platform workers. Finally, Chapter Five concludes with a summary of the main findings from this study.

[1] For example: Belgium, Portugal, Spain, France, Greece, Italy, and Malta.

[2] A rebuttable presumption is an assumption that may be accepted as true unless someone presents evidence to the contrary (rebutting evidence). This presumption places the burden of proof on the party opposing the presumed fact. The party against whom the presumption operates can try to present evidence to overcome or “rebut” the presumption, showing that the presumed fact is not true.

2. Methodology

For a regulation to be effective, it must have clearly defined objectives and undergo thorough scrutiny. This is particularly crucial in emerging policy fields such as the regulation governing the working conditions on digital platforms, which represent one of the first attempts to regulate the intersection of social and technological change.

Hastily drafted regulations can negatively impact firms, workers, and consumers. In the past, unclear objectives and inadequate frameworks for implementation have led to significant economic, social, and environmental costs. Consequently, international organisations consistently advocate for improved regulatory quality. To this end, guidelines and principles from the OECD or the World Economic Forum (WEF) have been published to ensure regulations are fit for purpose.

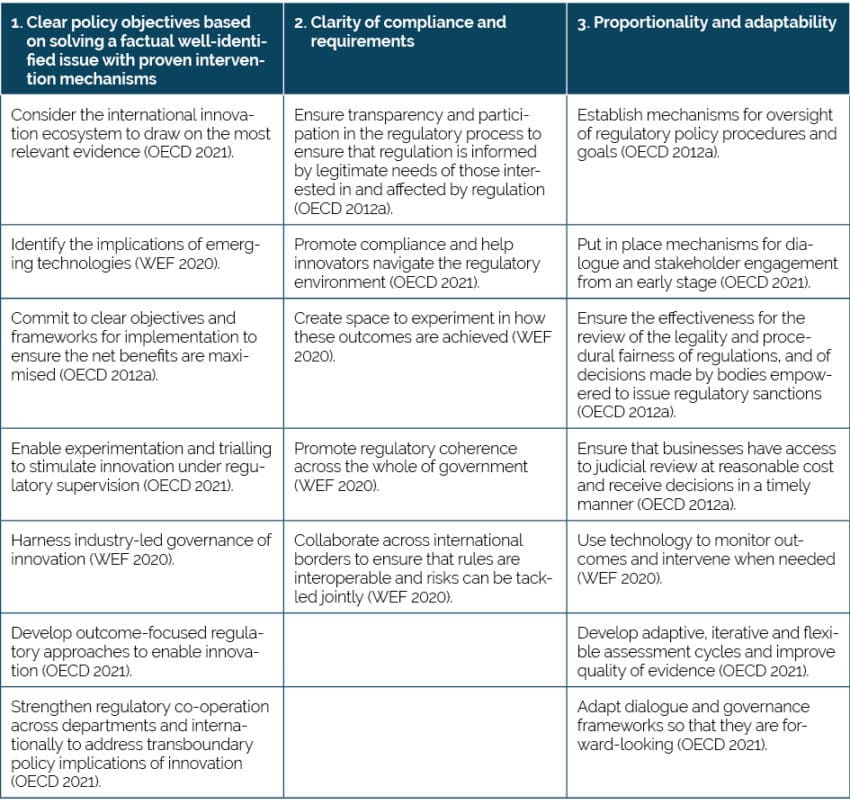

In its work, the OECD emphasises the importance of clear objectives and robust implementation frameworks as crucial to the efficiency of regulations. It also recommends ensuring transparency and participation in the regulatory process, to ensure regulations are informed by the legitimate needs of those affected. Similarly, the WEF stated that adaptability and learning mechanisms are centrally important for regulations to evolve, preventing them from becoming a source of economic harm. Based on this research, Table 2 distils three key principles of good regulatory design.

Table 2: Key principles of good regulations Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020). These principles were first presented in Bauer, Erixon, Guinea, van der Marel, and Sharma (2022).

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020). These principles were first presented in Bauer, Erixon, Guinea, van der Marel, and Sharma (2022).

Principle 1 advocates for regulations to be based on clear and consistent policy objectives, ensuring that the chosen regulatory instruments are capable of effectively achieving these objectives. It underscores the requirement for regulators to have a comprehensive understanding of market conditions, evolving technologies, and the potential impact of regulations on corporate behaviour.

Principle 2 emphasises the necessity for regulations to be comprehensible and clear, ensuring that those affected are well-informed and know how to comply. The importance of this principle is often overlooked, leading to unintended economic harm. Generally, businesses may hesitate to adopt or experiment with new technologies and business models if regulations are confusing and their practical implications are unclear.

Principle 3 delves into the concept of smart regulation. It advocates for regulators to actively learn from the outcomes of regulatory measures, engage with stakeholders impacted by these measures, and have mechanisms in place to manage trade-offs. This principle also includes the need for regulatory dialogue and judicial review, ensuring a responsive and adaptive regulatory environment.

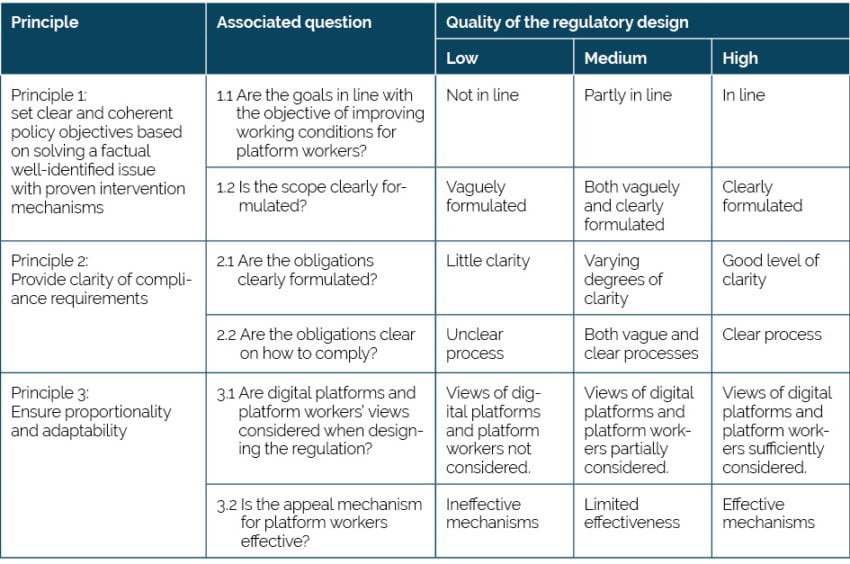

The next chapter evaluates the application of these principles of good regulatory design in the context of platform work regulation in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain. Table 3 presents these principles alongside related questions that guide the analysis in Chapter Three.

Table 3: Assessing platform work regulation Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020).

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020).

3. Assessing the Quality of Platform Work Regulation in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain

3.1 Principle 1: Clarity and Coherence of Objectives and Scope

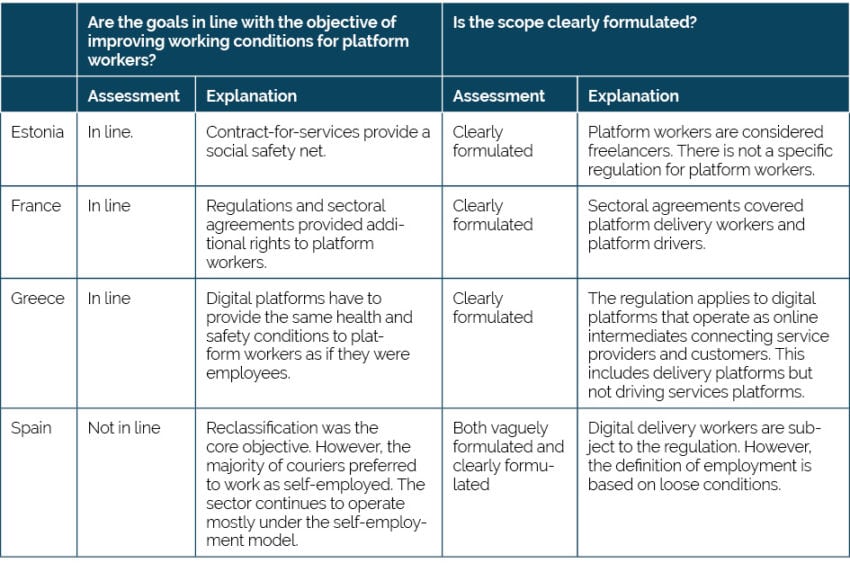

Regulations ought to be underpinned by clear and consistent policy objectives. This study proceeds on the assumption that the primary aim of policymakers in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain is the improvement of working conditions for platform workers. Nevertheless, the methods adopted by each of these countries exhibit considerable variation, reflecting an element of experimentation in determining the most effective regulatory structure. These differences can be attributed to the distinctive legal frameworks already in place in each country and the varied political perspectives influencing the regulatory systems.

Alignment of the regulation with the objective of improving working conditions for platform workers

The aim of the Spanish legislation[1] was to “clarify the right to information of workers in a digitalised labour environment, as well as the employment relationship in the field of digital delivery platforms” [2]. In terms of the employment relationship, the government opted to classify couriers as employees of the digital delivery platforms[3]. This decision was underpinned by the recognition that employees are entitled to more rights compared to the self-employed[4], and a belief that changing the employment status would grant additional rights to those working through digital delivery platforms[5].

Although platform workers in Spain sought better working conditions, they also wanted to retain the benefits of platform work: access to work and income, as well as flexibility and autonomy[6]. According to a survey, the majority of Spanish couriers emphasised that their primary motivations for engaging with digital platforms were access to work, the ability to start working quickly, and the flexibility of working hours[7].

However, the Spanish legislative approach represented an all-or-nothing shift, reclassifying couriers from self-employed status to employees without considering alternative arrangements that might have more closely aligned with the couriers’ preferences. For example, possibilities such as affording certain benefits to couriers while keeping them self-employed, or introducing a new category of workers in the Spanish labour code, were not properly considered.

In contrast, the French approach aims to “create conditions for maintaining these sectors within the realm of independent work while offering workers improved working conditions and remuneration” [8]. This framework did not materialise overnight; it has evolved through a series of legislative developments.

Initially, two laws laid the groundwork for social responsibilities of digital platforms towards platform workers. The “El Khomri” Law of 2016 underscored platforms’ social responsibility by addressing issues such as workers’ insurance coverage and professional training. This law also established fundamental rights for platform workers, including the right to strike, the right to form a trade union, and to represent their collective interests through it. Complementing this, the Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités (LOM) of 2019 granted platform workers the right to receive information from the digital platform before each trip proposal about the distance to be covered and the guaranteed price. It also provided the right to refuse a service proposal without any penalty, and the freedom to choose active and inactive periods of work. Furthermore, the LOM facilitated the creation of ARPE[9] (Autorité des Relations Sociales des Plateformes d’Emploi), a public body dedicated to nurture social dialogue between digital platforms and platform workers.

Additionally, six sectoral agreements signed by social partners (digital platforms and platform workers’ representatives), as outlined in the table below, address key concerns of platform workers. Some of these agreements came into effect in 2023, with others set to be enforced in 2024. These agreements cover critical issues such as the deactivation of workers’ accounts and minimum revenue guarantees[10]

Table 4: Sectoral agreement to reinforce the rights of independent platform delivery workers and drivers in France

The Greek regulation establishes platform worker’s right to participate in trade unions and engage in collective bargaining. Furthermore, the regulation delineates the responsibilities of digital platforms concerning the health and safety of their employees and platform workers. It stipulates: “digital platforms have towards the service providers, who are connected to them by independent service or work contracts, the same welfare, hygiene, and safety obligations that they would have towards them, if they were connected by labour contracts” [12]. In addition, digital platforms are obliged to communicate these rights to platform workers at the outset of their contracts. This ensures that workers are fully informed of their entitlements and the protections afforded to them under the regulatory framework.

In Estonia, the focus regarding platform workers is not primarily on their employment status; indeed, Estonia generally applies similar treatments to both employed and self-employed workers[13]. The paramount objective is to ensure adequate working conditions for all freelancers, including platform workers. A significant number of these workers in Estonia engage in a contract-for-services[14] (known as töövõtuleping) with digital platforms. This form of contract provides a social safety net, including unemployment benefits, sick pay, and healthcare services. However, it does not mandate a minimum wage, compulsory holiday periods, or working time limitations. Crucially, this model allows digital platforms to contribute to income tax, social security tax, employer’s social tax, and unemployment insurance taxes on behalf of the platform workers.

Clarity and coherence of scope

The Spanish regulation presumes an employment relationship under three conditions: (i) the activity must involve the delivery of any consumer product or merchandise; (ii) the employer company must exercise entrepreneurial faculties of organisation, direction, and control, be it directly, indirectly, or implicitly through a digital platform; and (iii) an algorithm must be used to manage the service or the working conditions. While the first condition narrows the scope of the law to digital delivery platforms[15], the second condition builds upon established principles derived from various court cases, presuming that firms organise, manage, and control the execution of labour.

The novelty of the law lies in the recognition of algorithms and digital platforms as means to organise, manage, and control labour conditions. In theory, the presumption of employment does not mandate an employment obligation on digital platforms. However, considering how digital platforms operate and the general conditions stipulated in the law, it becomes challenging for any digital platform to argue that it does not use an algorithm to manage the service it provides, and that it does not at least “indirectly or implicitly” organise offers of work or fees on its platform in accordance with the law. Any relationship established under a digital platform, following the prevailing business models, is likely to satisfy the broadly defined criteria regarding the “direct, indirect, or implicit” organisation, management, or control of labour by digital platforms. In the face of this presumption of employment, the onus is on digital platforms and platform workers to prove that their employment relationship is based on self-employment[16].

In France, the approach to regulating platform work is grounded in the principle that self-employment is the default employment status. The El Khomri Law and the Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités (LOM), in conjunction with the six sectoral agreements detailed in Table 4, constitute a clear and comprehensive regulatory framework. This framework delineates the rights and obligations of platform drivers and delivery workers.

Contrary to the specific focus on certain types of digital platforms in Spain (digital delivery) and France (digital delivery and ride-hailing), Greek regulation adopts a more inclusive approach, encompassing a wider array of digital platforms. These platforms are defined as companies operating “as intermediaries and through an online platform connect service providers or businesses or third parties with users or customers (…) and facilitate transactions between them.”[17] This definition covers delivery platforms and crowd-working platforms but excludes platforms providing driving services[18].

In Estonia, the regulatory framework primarily addresses the broader scope of self-employment, rather than introducing distinct regulations specifically for platform workers. As a result, there is no separate legislation dedicated exclusively to the regulation of platform work.

Conclusion

Principle 1 evaluates whether the objectives stated in the regulations are in line with the overarching aim of enhancing working conditions for platform workers. In addition, this principle scrutinises the scope and clarity of the regulation, specifically determining who is included under the regulation and who is not.

In Estonia, the focus on enhancing the quality of freelance work directly benefits platform workers. Measures such as the contract-for-services notably improve working conditions, and the scope of the regulation is articulated with clarity. In France, the regulations and the ensuing social dialogue, culminating in sectoral agreements between digital platforms and platform workers, aim to balance flexibility with adequate working conditions. Though these agreements are relatively recent, they have already shown positive impacts on working conditions, and the scope of the French regulations, including ARPE’s work, is clearly defined. In Greece, the regulation’s objectives of granting additional rights, enhancing health and safety conditions are in line with improving platform workers’ conditions. The regulation’s scope is also distinctly outlined. Conversely, in Spain, while the regulation intended to reclassify workers from self-employment to employment, many platform workers have clearly stated their preferences to remain independent. Furthermore, the approach to determining employment status, primarily based on the concept of control, resulted in a regulation that is vague and legally ambiguous. A summary of this assessment is presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Assessment of principle 1 clarity and coherence of objectives and scope

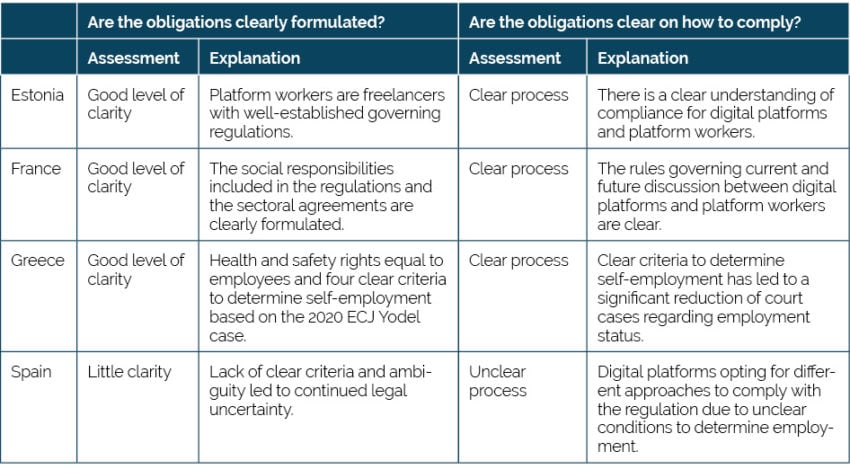

3.2 Principle 2: Clarity and Implementability of the Obligations

The second principle underscores the necessity of providing unequivocal guidelines regarding the obligations stipulated in the regulation and explicitly specifying how firms are expected to comply with them. Should the regulation introduce elements of confusion or ambiguity, there is a risk that companies might interpret and adhere to it in ways that diverge from the intentions of the regulators. Such deviations in compliance could significantly impede the government’s ability to realise its intended objectives.

Clarity of obligations and how to comply with them

As explained previously, Spanish regulation is hampered by a dual deficiency: it lacks precise criteria for determining employment status and imposes a broad, yet rebuttable, presumption that all platform workers are employees. The unclarity of the regulation, combined with the neglect of the individual preferences of platform workers who prefer self-employment, has led to a variety of compliance strategies among digital platforms. Some have maintained a self-employment model, albeit with adjustments to their organisational structures[19]; others have adopted a hybrid approach involving both subcontracting and self-employment; a few have transitioned to directly employing couriers; and some platforms have chosen to exit the Spanish market entirely following the implementation of the regulation.

Contrasting with the Spanish experience, Greece established clear criteria to determine the presumption of self-employment for platform workers. The Greek regulation articulates that “the contract between a digital platform and a service provider is presumed not to be dependent work, provided the service provider is entitled, based on its contract, cumulatively” to: (i) choose its working hours; (ii) maintain non-exclusivity, thus enabling workers to offer their services to other platforms and companies; (iii) determine the type and volume of work to be undertaken; and (iv) utilise subcontractors to perform the service[20]. These criteria draw upon the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruling in the case of Yodel in April 2020, thus offering a solid legal foundation[21].

Should these four conditions be met, platform workers can be classified as self-employed. The clarity of the law has helped digital platforms to comply with the regulatory requirements. Following the enactment of the regulation, digital platforms operating in Greece have aligned with the regulation, adhering to the specified standards and the four criteria for independent workers[22]. Prior to its introduction, there were numerous court cases regarding this issue[23]. However, following the adoption of the law, no new legal disputes concerning employment status between digital platforms and platform workers have emerged.

In Estonia, there is a well-defined understanding of the obligations of digital platforms and platform workers. As platform workers are categorised as self-employed, they are not subject to limitations on dress codes, working hours, declining offers, or working for multiple platforms. In instances where platform workers enter into a contract-for-services, digital platforms are required to register them with the Tax Office Employment Register[24].

The clarity of the regulatory framework and the obligations under the contract-for-services have led to good levels of compliance. Generally, Estonian platform workers appear to be satisfied with the balance between their rights and obligations[25]. To date, there have been no court rulings challenging a worker’s employment status or cases of reclassification. Moreover, the Estonian Government continues to regulate the sector, ensuring fairness across different employment statuses. For example, from 2024, online platforms[26] will be required to report the income of platform workers to the tax authorities for transactions exceeding €30 or a minimum annual revenue of €2,000[27]. This new obligation, which some digital platforms are already fulfilling[28], will enable tax authorities to verify the data reported by individuals, thus ensuring compliance and transparency in the platform economy[29].

The French approach to platform work builds upon the foundational El Khomri Law of 2016 and the Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités of 2019, which establish social responsibilities for digital platforms. As outlined in the previous principle, a third layer of the French approach involves sectoral bargaining and ARPE, which sets out a framework for future negotiations based on clear criteria: (i) each year, at least one mandatory theme (such as revenues, working conditions, risk prevention, professional skill development) must be discussed; (ii) for an agreement to be passed, it must garner support from at least one platform organisation and one or more platform workers’ organisations representing no less than 30 percent of the votes; and (iii) once an agreement is approved, it requires homologation by ARPE to become binding for the entire sector. The clarity of the rules governing the interactions between digital platforms and platform workers’ representatives supports the conclusion and correct implementation of the agreements.

Conclusion

Principle 2 stresses the necessity of clear guidelines delineating what digital platforms and platform workers are required to do to adhere to the regulation. This principle is upheld when the obligations set in the regulation are explicitly stated and accompanied by a straightforward compliance process. Additionally, it is vital that those affected by the regulation are well-informed and understand how to comply with these requirements. Essentially, the essence of Principle 2 lies in the clarity of obligations and the compliance process, as well as the awareness and understanding of those impacted.

In Estonia, platform workers are treated in the same way as other freelancers, with well-established and straightforward regulations governing self-employment. This clarity in the regulatory framework facilitates compliance. Greece has established clear criteria for determining the presumption of self-employment for platform workers. The clarity of this law in addressing the question of employment status has led to legal certainty and a marked reduction in the number of court cases, which also indicates better compliance with the law. The French government has implemented regulations that provide clear guidelines regarding the social responsibilities of digital platforms and a structured platform for discussions between digital platforms and platform workers. The rules governing these discussions are well-defined and have resulted in tangible outcomes. Conversely, in Spain, the absence of clear criteria to determine employment status and the broad assumption that all platform workers are employees have resulted in ambiguity regarding the responsibilities of digital platforms and platform workers. This lack of clarity is evidenced by the varied approaches digital platforms have taken to comply with Spanish regulations and the ongoing legal uncertainty surrounding the working conditions of digital delivery workers.

Table 6: Assessment of principle 2 clarity and implementability of the obligations

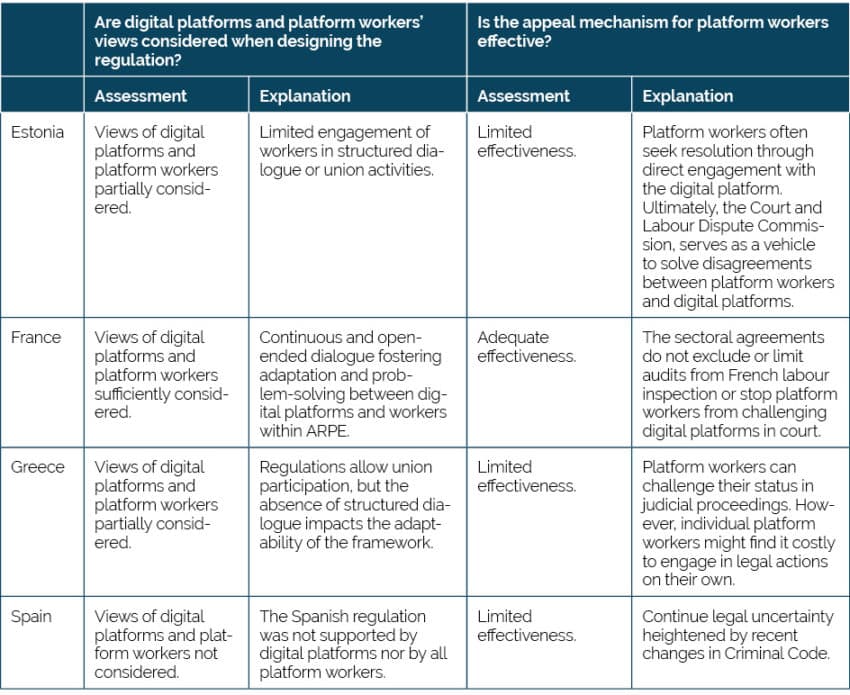

3.3 Principle 3: Regulatory Dialogue and Appeal Mechanism

Regulations should be both transparent and shaped by the needs of those who are directly interested in and affected by them. Additionally, it is vital that these regulations incorporate mechanisms enabling them to adapt and learn, ensuring that they remain specifically tailored to the problems they are designed to address.

This principle poses particular challenges in the digital platform sector. As a relatively young industry, digital platforms often do not have the same level of representation as larger, more established businesses in dialogues with regulators. Simultaneously, platform workers are not typically members of trade unions. Many of these workers, engaged in part-time roles, may not perceive a pressing need to invest time and effort in organising themselves. This issue is crucial, as it is common for governments to engage in discussions about the working conditions of platform work primarily with major trade union and business associations. However, these bodies do not always represent the interests of platform workers or digital platforms. A recent survey conducted among European couriers revealed that 66 percent felt their voices were not being heard by national policymakers. [30]

Regulatory dialogue and appeal mechanisms

The French approach to enhancing working conditions for platform workers encompasses a blend of regulations, sectoral agreements, and an ongoing, open-ended dialogue between digital platforms and platform workers, facilitated by ARPE. This model empowers both platform workers and digital platforms to actively participate and voice issues that are pertinent to them, acknowledging that they are the most informed about the matters at hand.

Creating a framework that convenes digital platforms and platform workers and establishes a process for discussing and agreeing on improved working conditions is not without its challenges. Notably, there was limited participation in the elections to select representatives of delivery workers and drivers, with only 1.83 percent participation among delivery workers and 3.9 percent among drivers[31]. While low levels of participation may be somewhat inherent in the sector and reflect the flexible nature of the work, the French system has successfully facilitated the creation of six sectoral agreements.

In situations where disputes arise regarding the implementation of these agreements, ARPE plays an instrumental role in guiding the discussions, ensuring they are constructive and result in substantive progress. This ongoing dialogue between the representatives of digital platforms and platform workers promotes a culture of learning from previous decisions. It also underpins the adaptation and improvement of the regulatory framework, thereby ensuring that it continues to be responsive and effective in meeting the changing needs of the platform economy. Furthermore, the sectoral agreements do not exclude or limit audits from French labour inspection or stop platform workers from challenging digital platforms in court.

The Spanish government adopted a different approach by agreeing to the so-called Rider’s Law in collaboration with the largest trade unions and business organisations. Notably, this agreement did not include representation from either digital platforms or the couriers themselves[32][33]. This lack of direct representation led to platform workers holding demonstrations against a law that was intended to grant them additional labour rights[34].

Instead of learning from the heterogeneous compliance and the challenges in delivering improved working conditions to platform workers, as described in Principles 1 and 2, the Spanish government amended the Criminal Code. This amendment makes repeated violations of the labour code a criminal offence, punishable by up to six years in prison. Some legal analyses have suggested that this change in the Criminal Code introduced further legal uncertainty[35].

Two key provisions in the Greek regulation facilitate future social dialogue between digital platforms and platform workers. The first provision enables platform workers to be represented in trade unions and participate in strikes. The second provision recognises that representative organisations have the right to negotiate and form sectoral collective agreements. Through these means, platform workers continue to voice demands for further improvements in their conditions of employment[36][37].

Additionally, the Greek regulation established an independent labour inspectorate tasked with verifying the legal relations between digital platforms and platform workers, and imposing sanctions in cases of legal breaches[38]. However, labour inspectors only investigate contracts involving employees, not those who are self-employed. Platform workers still have the option to challenge their employment status through judicial proceedings. If the court rules that the worker was wrongly classified, the digital platform would receive a financial penalty corresponding to the unpaid social security contributions. Despite this provision, individual platform workers might find engaging in legal actions prohibitively costly, thereby limiting their ability to seek redress. [39]

The challenges associated with the lack of engagement of platform workers and the difficulties they face in raising job-related concerns are also prevalent in Estonia. However, Estonia presents a unique case, as it is the OECD country with the lowest percentage of unionised workers — only 6.0 percent, compared to the OECD average of 15.8 percent[40]. Estonian platform workers have the option to join traditional trade unions. For instance, the Estonian Taxi Association represents the interests of all taxi drivers, including those who work via app-based platforms, and the Estonian Railwaymen’s Trade Union has extended membership to platform workers. However, it is relatively rare for Estonian platform workers to become members of these trade unions[41].

In cases of disagreement, platform workers often opt for direct engagement with the digital platform as a primary means of resolution. Ultimately, if disputes remain unresolved, the Court and Labour Dispute Commission, managed by the state, act as formal mechanisms for resolving disagreements between platform workers and digital platforms. Nevertheless, Estonian platform workers expressed concerns about their working conditions, particularly highlighting issues such as the lack of transparency in algorithmic management and the absence of structured social dialogue mechanisms[42].

Conclusion

France stands out for consistently upholding this principle. The French model is dedicated to the continual improvement of working conditions for platform workers through social dialogue. This process is dynamic and flexible, open to discussing new issues and revisiting established ones, thereby providing an adaptable framework for learning. In contrast, the approach in Spain did not garner support from either digital platforms or all courier’ associations. Rather than learning from this experience, the Spanish government responded by escalating penalties for non-compliance with the regulation. In the case of Greece, while its regulation has enabled platform workers to unionise and engage in collective bargaining, significantly reducing court cases, it has not fully addressed the challenges these workers face in organising themselves and articulating their concerns. Similarly, Estonia lacks a bespoke structure tailored to address the specific concerns of platform workers.

Table 7: Assessment of principle 3 dialogue and appeal mechanisms

[1] For a complete review of the Spanish Law 12/2021 see Forteza, J. L., & Sánchez, V. G. (2023).

[2] “El presente real decreto-ley cuenta con un artículo y dos disposiciones finales, cuya finalidad es la precisión del derecho de información de la representación de personas trabajadoras en el entorno laboral digitalizado, así como la regulación de la relación trabajo por cuenta ajena en el ámbito de las plataformas digitales de reparto.” Law 12/2021, de 28 de septiembre, por la que se modifica el texto refundido de la Ley del Estatuto de los Trabajadores, aprobado por el Real Decreto Legislativo 2/2015, de 23 de octubre, para garantizar los derechos laborales de las personas dedicadas al reparto en el ámbito de plataformas digitales.

[3] Europa Press (2021, June 10). Yolanda Díaz defiende la ‘ley rider’: Nadie se plantea escoger entre ser laboral o autónomo en una fábrica. Europa Press, Retrieved from https://www.europapress.es/economia/laboral-00346/noticia-yolanda-diaz-defiende-ley-rider-nadie-plantea-escoger-ser-laboral-autonomo-fabrica-20210610122851.html

[4] ESADE (2022). Ley Rider: Un año despues.

[5] Digital platforms have the right to demonstrate that the employment status with platform workers is based on self-employment.

[6] Gozzer, S. (2021, September 09). Spain had a plan to fix the gig economy. It didn’t work. Wired, Retrieved from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/spain-gig-economy-deliveroo

[7] SIGMADOS (2021). Estudio repartidores de comida a domicilio.

[8] “L’objectif poursuivi est double: créer les conditions d’un maintien de ces secteurs dans la sphère du travail indépendant tout en offrant aux travailleurs de meilleures conditions de travail et de rémunération”. Source: ARPE. (2023). Le dialogue social dans le secteur des plateformes d’emploi. Retrieved from: https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/actualites/trois-accords-finalises-pour-ameliorer-les-droits-des-livreurs-independants/

[9] The obligations of the ARPE regarding its functioning, organisation, and funding have been enacted in the decree n° 2021-1461 of 8th November 2021.

[10] It is important to acknowledge that the French approach was enabled by the European Commission Guidelines on collective bargaining of self-employed which ensure that competition law does not stand in the way of collective agreements to improve the working conditions of certain self-employed persons in a number of sectors including digital platforms.

[11] The “adversarial principle” guarantees each party the right to know the arguments, law and evidence on the basis of which it will be judged.

[12] “Οι ψηφιακές πλατφόρμες έχουν έναντι των παρόχων υπηρεσιών, που είναι φυσικά πρόσωπα και συνδέονται μαζί τους με συμβάσεις ανεξάρτητων υπηρεσιών ή έργου, τις ίδιες υποχρεώσεις πρόνοιας, υγιεινής και ασφάλειας που θα είχαν έναντι αυτών, αν συνδέονταν μαζί τους με συμβάσεις εξαρτημένης εργασίας, της σχετικής νομοθεσίας εφαρμοζομένης αναλογικώς”. Source: Law no. 4808/2021. (2021). Retrieved from Taxheaven: https://www.taxheaven.gr/law/4808/2021

[13] For example, self-employed workers pay 20 percent on income tax which is the same rate paid by employees. Under the Entrepreneurship bank account system, every euro received in that bank account is taxed at 20 percent at the source.

[14] Contract-for-services are described in Chapter 36 of the Law of Obligations Act. Platform workers can also choose to offer their work in digital platforms using a legal entity which allows workers to deduct work-related costs but it requires more accounting work. Not all platforms allow platform workers to choose a contract for services. For taxi drivers, the limited liability company status is the most commonly chosen option.

[15] The Spanish law does not justify why the sub-sector of digital delivery platforms is target especially within the overall sector of digital platforms.

[16] In legal terms this is known as rebuttable presumption which is an assumption that may be accepted as true unless someone presents evidence to the contrary (rebutting evidence). This presumption places the burden of proof on the party opposing the presumed fact. The party against whom the presumption operates can try to present evidence to overcome or “rebut” the presumption, showing that the presumed fact is not true in the particular case.

[17] “Ψηφιακές πλατφόρμες» καλούνται οι επιχειρήσεις που ενεργούν είτε απευθείας είτε ως μεσάζοντες και μέσω διαδικτυακής πλατφόρμας συνδέουν παρόχους υπηρεσιών ή επιχειρήσεις ή τρίτους με χρήστες ή πελάτες ή καταναλωτές και διευκολύνουν τις μεταξύ τους συναλλαγές ή συναλλάσσονται απευθείας μαζί τους.” Source : Law no. 4808/2021. (2021). Retrieved from Taxheaven: https://www.taxheaven.gr/law/4808/2021

[18] Platforms offering taxi services are categorised as transport companies according to the 2018 transport Law. These platforms are subject to the same regulations as traditional taxi companies and drivers are self-employed.

[19] For instance, measures to increase the freedom of riders or eliminating any economic penalty or sanction to those refusing to take orders. Forteza, J. L., & Sánchez, V. G. (2023).

[20] “Η σύμβαση μεταξύ ψηφιακής πλατφόρμας και παρόχου υπηρεσιών τεκμαίρεται ότι δεν είναι εξαρτημένης εργασίας, εφόσον ο πάροχος υπηρεσιών δικαιούται, βάσει της σύμβασής του, σωρευτικά”. Source: Law no. 4808/2021. (2021). Retrieved from Taxheaven: https://www.taxheaven.gr/law/4808/2021

[21] The Greek regulation and the four requirements that determine employment status borrow from the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruling in the case of Yodel in April 2020, which sets a legal foundation for worker status clarification. The ECJ ruled that the classification of a worker as an employee or an independent contractor under national law does not prevent that person from being classified as an employee under EU law if their independence is merely notional, thereby disguising an employment relationship. The ruling sets out four conditions for a worker to be considered as independent: (i) ability to use subcontractors to perform the service (i.e. delegation right); (ii) ability to choose clients or tasks; (iii) ability to provide services to competitors; and (iv) ability to choose the number of working hours.

[22] Business Daily. (2023, April). Wolt: Έχουμε αυξήσει τις αμοιβές των συνεργατών διανομέων. Retrieved from Business Daily: https://www.businessdaily.gr/epiheiriseis/84190_wolt-ehoyme-ayxisei-tis-amoibes-ton-synergaton-dianomeon

[23]Enosis, E. (2021, September 20). Υπ. Εργασίας: Το καθεστώς απασχόλησης στις ψηφιακές πλατφόρμες στην Ευρώπη – Πριν και μετά το νόμο για την Προστασία της Εργασίας. Taxheaven, Retrieved from https://www.taxheaven.gr/news/56105/yp-ergasias-to-kaoestws-apasxolhshs-stis-pshfiakes-platformes-sthn-eyrwph-prin-kai-meta-to-nomo-gia-thn-prostasia-ths-ergasias

[24] Wolt. Contract types. Wolt Courier Partner in Estonia. Retrieved 8 November 2023, from https://woltpartner.ee/contracts

[25] Sommer, R. (2021, November 2). Wolt ei ole nõus käsitlema kullereid ettevõtte töötajatena. Praegusega on rahul ka Eesti kullerid. DELFI, Retrieved from https://arileht.delfi.ee/artikkel/95030825/wolt-ei-ole-nous-kasitlema-kullereid-ettevotte-tootajatena-praegusega-on-rahul-ka-eesti-kullerid

[26] Reporting platforms are defined as any software, including a website or part thereof and applications, including mobile applications, accessible by users and enabling sellers to be connected to other users for the purpose of conducting targeted activity, directly or indirectly, with those users.

[27] Amendment of the Tax Information Exchange Act and the Tax Organization Act (transposition of the Administrative Cooperation Directive), 2022 https://www-riigiteataja-ee.translate.goog/akt/129122022001?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=wapp

[28] Kiisler, I., & Aaspõllu, H. (2023, September 15). Veebiplatvormide töötajate maksustamine jõuab seadusesse. ERR, Retrieved from https://www.err.ee/1609101641/veebiplatvormide-tootajate-maksustamine-jouab-seadusesse

[29] This obligation stemmed from Estonia’s adoption of the DAC7 tax directive, which mandates digital platform operators within the EU to report personal and business information of their providers to tax authorities. Failure on the part of platform managers to comply with the reporting obligation can lead to penalties. Furthermore, platform managers who fail to meet this new obligation may find their activities partially or completely blocked by the Tax Board.

[30] Taloustutkimus (2023)

[31] Minister of Labour (M. O. Dussopt) at the National Assembly, Thursday 25th May 2023. Retrieved from: https://videos.assemblee-nationale.fr/video.13465809_646f0be54add8.revelations-des-uber-files–m-olivier-dussopt-ministre–m-clement-beaune-ministre–mme-elisab-25-mai-2023

[32] Glovo was a member of a relevant business organisation but left before the Rider’s law was adopted.

[33] AAR (2021, June 25). Nuestras Propuestas de Enmiendas. Retrieved from: https://autoriders.es/enmiendas/

[34] RTVE (2023, October). Alrededor de 4.000 ‘riders’ salen a la calle para pedir a los diputados que no convaliden el decreto del Gobierno. RTVE, Retrieved from https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20210511/manifestaciones-contra-ley-riders/2089621.shtml

[35] elEconomista. (2023, February 09). Los expertos piden aclarar la reforma penal que lleva al empresario a prisión. elEconomista, Retrieved from https://www.eleconomista.es/legal/noticias/12141660/02/23/Los-expertos-piden-aclarar-la-reforma-penal-que-lleva-al-empresario-a-prision.html

[36] Giantzis, A. (2023, April 03). Wolt strike against pay cuts. EFSYN, Retrieved from https://www.efsyn.gr/oikonomia/elliniki-oikonomia/384471_enantia-stis-meioseis-ton-amoibon-i-apergia-sti-wolt

[37] Martinelli, F. (2021). Lights on! Worker and social cooperatives tackling undeclared work. CECOP.

[38] EES (2023). Organization Profile. Retrieved from Hellenic labour Inspectorate: https://www.hli.gov.gr/organismos/profil/

[39] ETUC (2023). Greece: Country report 2022. ETUC.

[40] OECD (2023). Trade Union Dataset.

[41] Holts, K. (2022).

[42] Holts, K. (2022).

4. Policy Recommendations

This Policy Brief has conducted a comparative analysis of the legislative approaches to platform workers’ working conditions in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain, using established principles of good regulation as a benchmark. The analysis reveals the diverse strategies employed by these countries and the potential areas for improvement in each national context. Based on this analysis, this Chapter presents four policy recommendations for policymakers to consider when contemplating the regulation of working conditions for platform workers.

- Harness the benefits of digital platforms for platform workers

Digital platforms offer platform workers significant advantages, including access to work, income opportunities, flexibility, and autonomy. Policymakers pursuing policies to improve the working conditions of platform workers should ensure that these benefits are preserved.

Digital platforms are particularly significant for individuals who find it challenging to secure traditional employment, such as young people, immigrants, and individuals with disabilities. They not only make work more accessible and reduce job search times but also create new job types, some of which may not have existed previously or were confined to the informal sector. This access to work is especially crucial in regions with high youth unemployment, such as Greece, Spain, or Italy, where rates are notably high[1]. Digital platforms also offer an avenue for individuals to boost their income. For instance, 72 percent of delivery workers view platform work as an additional activity (see Box 1). At the other end of the spectrum, professionals like coders and consultants use digital platforms to offer their expertise globally, allowing them to secure work from the highest bidder.

Furthermore, several studies indicate that a significant proportion of platform workers report higher levels of job satisfaction compared to their counterparts in other sectors[2], which underscores the value of autonomy and flexibility in these roles. A survey revealed that approximately two-thirds of couriers cite flexibility as the main reason for their engagement in the delivery sector[3]. Notably, nearly 70 percent of couriers expressed a preference for flexibility over fixed schedules, even if this choice entailed foregoing a 15 percent increase in income[4].

These advantages are pivotal in influencing platform workers’ decisions to offer services via digital platforms. Consequently, it is imperative for policymakers to prioritise the preservation of these benefits when developing the regulatory frameworks that govern the working conditions in digital platforms.

- Improve the working conditions for platform workers independently of their employment status

While access to work, income opportunities, flexibility, and autonomy are essential elements for the welfare of platform workers, these factors alone are insufficient to ensure adequate working conditions. For instance, Greece has assigned responsibility to digital platforms for the health and safety of platform workers, similar to their obligations towards employees. In France, digital platforms bear social responsibilities towards platform workers, including providing occupational risk insurance. In Estonia, self-employed platform workers engage in contracts-for-services with digital platforms, which, under specific conditions, include healthcare coverage.

These improvements in working conditions were achieved without having to reclassify platform workers from self-employed to employees. Essentially, platform workers have been able to maintain the benefits of self-employment while significantly improving their working conditions.

The examples from Greece, France, and Estonia stand in contrast with the strategy adopted in Spain, which relies on reclassifying platform workers from self-employed to employees. The fundamental flaw in Spain’s approach is the marked disparity in employment rights between employees and the self-employed, a discrepancy that existed well before the rise of digital platforms. Employees in Spain are entitled to labour rights such as sick pay, protection against unfair dismissal, and a minimum wage – privileges not extended to self-employed individuals.[5] This disparity is not unique to Spain. However, the case of France and Greece demonstrate that policymakers have viable alternatives at their disposal. It is entirely feasible to recognise the unique circumstances of platform workers and grant them additional rights while preserving their self-employed status, and retaining the benefits associated with this form of employment.

- Establish clear employment status criteria

In countries where the legal framework differentiates between various types of workers, the issue of employment status is likely to require close attention. The experiences of Greece, when defining self-employment, and Spain, when defining employment, offer valuable insights in this regard.

Inspired by the ECJ ruling in the Yodel case, Greece enshrined into law four explicit conditions that a digital platform must adhere to for a platform worker to be classified as self-employed. The establishment of clear criteria has yielded benefits for digital platforms, which now understand the conditions their contractual offers must satisfy, and for platform workers, who have gained clarity in assessing their employment status.

In contrast, Spanish legislation has adopted a rebuttable presumption of employment under ambiguous conditions. In Spain, employment status is closely linked to the concept of control. If a digital platform organises, manages, or exercises control over labour in any direct, indirect, or implicit manner, the platform worker is categorised as an employee. The broad nature of this definition poses a challenge for digital platforms in ascertaining whether a contractual relationship with a platform worker qualifies as self-employment. Furthermore, determining what constitutes organisation, management or control of labour is notably difficult. These concepts are open to interpretation, unlike the clear criteria for defining self-employment for platform workers introduced in Greece.

The divergent approaches have led to markedly different outcomes. In Greece, there has been a substantial reduction in court cases concerning reclassification. Conversely, in Spain, the model of self-employment continues to predominate, accompanied by ongoing legal uncertainty for both digital platforms and platform workers.

- Empower platform workers’ representation

A critique of the digital platform economy concerns the limited bargaining power often faced by the self-employed, as they typically work in isolation from one another. This isolation makes organising sectoral representation to safeguard their interests more challenging. Additionally, a significant proportion of platform workers are engaged in part-time work and do not solely rely on digital platforms for their income. These factors diminish their incentive to participate in trade unions.

Addressing this issue presents challenges, yet it is a crucial aspect of devising effective regulation. This is because the preferences of policymakers may not always align with those of platform workers. Additionally, platform workers and digital platforms possess information that policymakers might lack.

Among the examined countries, France has placed this issue at the heart of its strategy to regulate the working conditions of platform workers. The establishment of ARPE in France exemplifies how an institution can act as a facilitator, aiding platform workers in organising themselves. ARPE also supports the development of rules governing interactions between workers and digital platforms, providing support to both parties in reaching agreements and resolving disputes.

In theory, traditional unions could act as representatives for platform workers. Nonetheless, certain characteristics inherent in the work performed by platform workers complicate their representation by traditional trade unions. Typically, platform workers are self-employed and have distinct needs that diverge from those of employees. For instance, they highly value flexibility and autonomy, often engaging with multiple platforms simultaneously and adhering to fluid schedules, which does not always align with the conventional demands of a fixed working day and an exclusive employment relationship. Consequently, this has led to the emergence of specialised trade unions and associations that represent the interests of platform workers.

However, many of these nascent trade unions and associations are often excluded from the social dialogue in numerous countries, which traditionally involves the largest trade unions and business associations. In Spain, for example, the regulations governing the working conditions of platform workers were negotiated by trade unions and business associations that did not necessarily represent the viewpoints of digital platforms or the majority of platform workers. In contrast, the French model addresses this challenge by facilitating the election of representatives for platform workers and establishing rules for engagement between both parties to ensure balanced negotiations.

In this context, it is important to recognise that amendments to the European Commission Guidelines on collective bargaining, instrumental in facilitating the French approach to platform work, have now paved the way for incorporating freelancers’ interests in negotiating working conditions across various sectors[6]. This development may lead to new models of social dialogue.

[1] Eurostat (2023). Unemployment rate measured as percentage of population in the labour force.

[2] Berger, T., Frey, C. B., Levin, G., & Danda, S. R. (2019).

[3] SIGMADOS (2021). Estudio repartidores de comida a domicilio.

[4] Basalisco, B., Marquardt, G., & May Hansen, M. (2021). Study of the value of flexible work for local delivery couriers. Copenhagen Economics.

[5] ESADE (2022). Ley Rider: Un año despues.

[6] European Federation of Journalists (2023, August 11). Collective bargaining for EFJ’s solo self-employed. European Federation of Journalists, Retrieved from https://europeanjournalists.org/blog/2023/08/11/collective-bargaining-for-efjs-solo-self-employed/

5. Conclusion

The comparative analysis of the regulatory frameworks governing the working conditions of platform workers in Estonia, France, Greece, and Spain yields vital insights for policymakers devising or considering similar regulations. This Policy Brief offers a comprehensive understanding of the potential impacts and challenges of the four regulatory strategies.

The examination of the four regulatory frameworks is conducted in accordance with three well-established principles of good regulation adapted from the OECD and the WEF for the assessment of the regulations of the working conditions on digital platforms: (i) clarity and coherence in the objectives and scope of the regulation; (ii) clarity and implementability of the obligations; (iii) the presence of regulatory dialogue and appeal mechanisms.

Our analysis assumes that the principal objective of policymakers is to enhance the working conditions of platform workers. To achieve this objective, it is necessary to consider platform workers’ preferences and concerns. In addition to ensuring adequate welfare, safety, and health conditions, it is crucial to acknowledge that platform workers highly value access to work, income opportunities, flexibility and autonomy. These aspects are not only essential features of platform work but also important reasons for individuals to offer their labour through digital platforms. Moreover, these attributes are commonly associated with self-employment. The experience of Greece, France, and Estonia indicates that it is perfectly possible to enhance the working conditions of platform workers while maintaining their status as independent workers.

Policymakers should also provide unequivocal guidelines regarding the obligations stipulated in their regulations and explicitly detail how firms are expected to comply. In the realm of platform work, a lack of clear rules can lead to diverse interpretations and strategies among digital platforms, potentially causing significant challenges. Spain exemplifies such a scenario. The broad conditions for determining employment status have resulted in a variety of compliance strategies among digital platforms, with some even opting to withdraw from the Spanish market. This high degree of uncertainty, stemming from the ambiguity in the regulation, adversely affects not only digital platforms but also platform workers, who face difficulties in accurately assessing their employment status.

Many of the issues identified in this Policy Brief will be solved if policymakers would set up structures for effective dialogue and appeal mechanisms. This action will not only ensure that those who are affected by the regulation can shape the regulation but it will also offer a platform for digital platforms and platform workers to provide input to policymakers so regulations can improve in the future. ARPE in France and the amendments to the European Commission Guidelines on collective bargaining offer examples of new models of social dialogue between digital platforms and platform workers.

In light of the findings from our comparative analysis, this Policy Brief offers four policy recommendations for policymakers grappling with the complexities of regulating the working conditions of platform workers. These recommendations are geared towards designing a regulatory framework that both preserves the inherent benefits of digital platforms and prioritises the well-being of platform workers. As policymakers navigate the evolving landscape of the future of work, this study serves as a guidepost, assisting in the development of effective and balanced regulation.

References

AAR (2021, June 25). Nuestras Propuestas de Enmiendas. Retrieved from https://autoriders.es/enmiendas/

Amendment of the Tax Information Exchange Act and the Tax Organization Act (transposition of the Administrative Cooperation Directive), 2022. Retrieved from https://www-riigiteataja-ee.translate.goog/akt/129122022001?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=wapp

ARPE (2023, April 20). Accord du 20 avril 2023 encadrant les modalités de rupture des relations commerciales entre les travailleurs indépendants et les plateformes de mise en relation. Retrieved from https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Accord-Desactivations-20.04.2023.pdf

ARPE (2023, April 21). Trois accords pour améliorer les droits des livreurs indépendants. Retrieved from https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/actualites/trois-accords-finalises-pour-ameliorer-les-droits-des-livreurs-independants/

ARPE (2023, January 18). Accord du 18 janvier 2023 créant un revenu minimal par course dans le secteur des plateformes VTC. Retrieved from https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Accord-sur-le-revenu-minimal-du-18-janvier-2022.pdf

ARPE (2023, January 18). Accords du 18 janvier 2023 relatif à la méthode et aux moyens de la négociation dans le secteur des plateformes VTC. Retrieved from https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/accord_de_methode_vtc___18_janvier_2023.pdf

ARPE (2023, September 19). Communique de presse. Retrieved from https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/CP-_-Accord-VTC-transparence-et-desactivation_-ARPEvf.pdf

ARPE (2023, September 21). Enjeux et objectifs. Retrieved from https://www.arpe.gouv.fr/

Bauer, M., Erixon, F., Guinea, O., van der Marel, E., & Sharma, V. (2022). The EU Digital Markets Act: Assessing the Quality of Regulation. Report, ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 02/2022, 31 p.

Basalisco, B., Marquardt, G., & May Hansen, M. (2021). Study of the value of flexible work for local delivery couriers. Copenhagen Economics.

Berger, T., Frey, C. B., Levin, G., & Danda, S. R. (2019). Uber happy? Work and well-being in the ‘gig economy’. Economic Policy, 34(99), 429-477.

Bertuzzi, L. (2023, July 19). EU Commission mulls rules on algorithmic management in workplace for next mandate. Euractive, Retrieve from https://www.euractiv.com/section/artificial-intelligence/news/eu-commission-mulls-rules-on-algorithmic-management-in-workplace-for-next-mandate/

Business Daily. (2023, April). Wolt: Έχουμε αυξήσει τις αμοιβές των συνεργατών διανομέων. Business Daily, Retrieved from: https://www.businessdaily.gr/epiheiriseis/84190_wolt-ehoyme-ayxisei-tis-amoibes-ton-synergaton-dianomeon

CEDEFOP (2023). Skills Intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/tools/skills-intelligence/self-employment?year=2021&country=EL#11

de Baudouin, P. (2021, September 21). Deliveroo renvoyé devant le tribunal correctionnel de Paris pour travail dissimulé. Retrieved from https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/paris-ile-de-france/paris/deliveroo-renvoye-devant-le-tribunal-correctionnel-de-paris-pour-travail-dissimule-2259922.html

Deliveroo. (2023). Ride with Deliveroo: Work that fits around your life. Retrieved from https://riders.deliveroo.fr/en/apply

EES (2023). Organization Profile. Retrieved from Hellenic labour Inspectorate: https://www.hli.gov.gr/organismos/profil/

elEconomista (2023, February 09). Los expertos piden aclarar la reforma penal que lleva al empresario a prisión. elEconomista, Retrieved from https://www.eleconomista.es/legal/noticias/12141660/02/23/Los-expertos-piden-aclarar-la-reforma-penal-que-lleva-al-empresario-a-prision.html

Enosis, E. (2021, September 20). Υπ. Εργασίας: Το καθεστώς απασχόλησης στις ψηφιακές πλατφόρμες στην Ευρώπη – Πριν και μετά το νόμο για την Προστασία της Εργασίας. Taxheaven, Retrieved from https://www.taxheaven.gr/news/56105/yp-ergasias-to-kaoestws-apasxolhshs-stis-pshfiakes-platformes-sthn-eyrwph-prin-kai-meta-to-nomo-gia-thn-prostasia-ths-ergasias

ESADE (2022). Ley Rider: Un año despues.

ETUC (2023). Greece: Country report 2022. ETUC.

Europa Press (2021, June 10). Yolanda Díaz defiende la ‘ley rider’: Nadie se plantea escoger entre ser laboral o autónomo en una fábrica. Europa Press, Retrieved from https://www.europapress.es/economia/laboral-00346/noticia-yolanda-diaz-defiende-ley-rider-nadie-plantea-escoger-ser-laboral-autonomo-fabrica-20210610122851.html

European Commission (2021). Commission Staff Working Document on Better Regulation Guidelines. November 2021

European Commission (2023). Commission Staff Working Document on Better Regulation Toolbox. July 2023

European Federation of Journalists (2023, August 11). Collective bargaining for EFJ’s solo self-employed. European Federation of Journalists, Retrieved from https://europeanjournalists.org/blog/2023/08/11/collective-bargaining-for-efjs-solo-self-employed/

Eurostat (2023). Unemployment rate measured as percentage of population in the labour force.

Forteza, J. L., & Sánchez, V. G. (2023). Regulación laboral en España de las plataformas digitales: Presente y futuro. Revista de Estudios Jurídico Laborales y de Seguridad Social (REJLSS), (7), 36-55.

Frouin, J.-Y. (2020). Réguler les plateformes numériques de travail.

Giantzis, A. (2023, April 03). Wolt strike against pay cuts. EFSYN, Retrieved from https://www.efsyn.gr/oikonomia/elliniki-oikonomia/384471_enantia-stis-meioseis-ton-amoibon-i-apergia-sti-wolt

Gozzer, S. (2021, September 09). Spain had a plan to fix the gig economy. It didn’t work. Wired, Retrieved from https://www.wired.co.uk/article/spain-gig-economy-deliveroo

Holts, K. (2022). Platvormitöö tegijate organiseerumine Eestis. Tallinn: Sotsiaalministeerium

Jacquin, O. (2023, January 19). Directive sur les travailleurs des plateformes: Question d’actualité au gouvernement n°0187G – 16e législature. Récupéré sur Senat: https://www.senat.fr/questions/base/2023/qSEQ23010187G.html

Kiisler, I., & Aaspõllu, H. (2023, September 15). Veebiplatvormide töötajate maksustamine jõuab seadusesse. ERR, Retrieved from https://www.err.ee/1609101641/veebiplatvormide-tootajate-maksustamine-jouab-seadusesse

Law of Obligations Act, RT I 2001, 81, 487 § 36 (2022). https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/508012022001/consolide#

LeedsIndex. (2023). Leeds Index of Platform Labour Protest. Retrieved from https://leeds-index.co.uk/resources/

Léfifrance. (2022, April 07). Ordonnance n° 2022-492. Retrieved from https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000045522912

Minister of Labour (M. O. Dussopt) at the National Assembly, Thursday 25th May 2023. Retrieved from: https://videos.assemblee-nationale.fr/video.13465809_646f0be54add8.revelations-des-uber-files–m-olivier-dussopt-ministre–m-clement-beaune-ministre–mme-elisab-25-mai-2023

OECD (2006). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Alternatives to Traditional Regulation.

OECD (2012a). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance.

OECD (2012b). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Regulatory Reform and Innovation.

OECD (2013). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Regulatory Cooperation: Addressing Global Challenges.

OECD (2014). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections.

OECD (2018b). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit.

OECD (2019). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Regulatory effectiveness in the era of digitalisation.

OECD (2020a) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Cracking the code: Rulemaking for humans and machines.

OECD (2020b). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, One-Stop Shops for Citizens and Business.

OECD (2020c). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Regulatory Impact Assessment.

OECD (2021). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Recommendation of the Council for Agile Regulatory Governance to Harness Innovation.

Oyer, P. (2020). The gig economy. IZA World of Labor.

Patricio, S. (2024, January 16). Aumento das visitas da ACT pode prejudicar qualidade da inspeção, avisa sindicato. Trabalho, Retrieved from: https://eco.sapo.pt/2024/01/16/aumento-das-visitas-da-act-pode-prejudicar-qualidade-da-inspecao-avisa-sindicato/

Piasna, A., Zwysen, W., & Drahokoupil, J. (2022). The platform economy in Europe: results from the second ETUI internet and platform work survey. ETUI AISBL.

PPMI (2021). Study to support the impact assessment of an EU initiative to improve the working conditions in platform work. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

RTVE (2023, October). Alrededor de 4.000 ‘riders’ salen a la calle para pedir a los diputados que no convaliden el decreto del Gobierno. RTVE, Retrieved from https://www.rtve.es/noticias/20210511/manifestaciones-contra-ley-riders/2089621.shtml

Serra, J. (2023, October 18). Work on digital platforms: presumption of employment contract. Portugal Resident, Retrieved from: https://www.portugalresident.com/work-on-digital-platforms-presumption-of-employment-contract/

SIGMADOS (2021). Estudio repartidores de comida a domicilio.

Sommer, R. (2021, November 2). Wolt ei ole nõus käsitlema kullereid ettevõtte töötajatena. Praegusega on rahul ka Eesti kullerid. DELFI, Retrieved from https://arileht.delfi.ee/artikkel/95030825/wolt-ei-ole-nous-kasitlema-kullereid-ettevotte-tootajatena-praegusega-on-rahul-ka-eesti-kullerid

Taloustutkimus (2023). Only 23% of Wolt couriers have heard about EU’s Platform Work Directive – pan-European study shows platform workers know what they want, but are not being heard. Wolt, Retrieved from https://blog.wolt.com/hq/2023/05/09/pan-european-study-shows-platform-workers-know-what-they-want-but-are-not-being-heard/

Vallistu, J., & Piirits, M. (2021). Platvormitöö Eestis 2021. Küsitlusuuringu tulemused. Arenguseire Keskus.

WEF (2021). Agile Regulation for the Fourth Industrial Revolution A Toolkit for Regulators, December 2020.

WTO (2021), Adapting to the digital trade era: challenges and opportunities, World Trade Organizatio.