Published

National Insecurity: Transatlantic Distress over Market Concentration

By: Hosuk Lee-Makiyama Guest Author

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union North-America

This piece was co-authored with Robin Baker, a Research Associate at the London School of Economics.

Tech market concentration is only an issue when you don’t have a horse in the race. At least, that is the message conveyed by transatlantic policy makers. At recent bilateral summits US officials have expressed concerns over the Ericsson-Nokia 5G ‘duopoly’. In response, their European counterparts have argued that ‘Big Tech’ has become overly dominant in a multitude of important sectors.

Brussels, acting as a proxy for Paris and Berlin (who in turn represent European retail and media conglomerates), is hell-bent on tackling Silicon Valley’s dominant ‘online platforms’. This loosely defined concept can refer to virtually any company that is not European, successful and challenges old-fashioned business models. The seemingly-fluid nature of this umbrella is perhaps best illustrated by Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, which bundles together search engines, shopping and booking sites, operating systems and a host of other services.

Understandably, US diplomats, analysts and lobbyists loudly object to EU policies. Despite de facto monopolies in search engines, social media, operating systems and certain internet software, they reason that internet giants operate in well-functioning markets. The frequently cited theory of dynamic competition advocates that market shares of up to 93 percent are not necessarily problematic and may be more conducive to innovation. From this standpoint, EU regulations and antitrust enforcement must be decidedly ‘protectionist’.

In D.C, on the other hand, 5G technology and telecoms infrastructure have been subject to greater scrutiny. Against a backdrop of geopolitical bifurcation, the US Government’s campaign against Huawei is well publicised, but other firms have not been immune to unorthodox industrial policy. Open RAN has been hailed as a possible solution to 5G market concentration and the United States Innovation and Competition Act pledges billions of potentially non-WTO compliant subsidies to create domestic alternatives and break the market dominance of European and Korean players.

Somehow, the very same people who see no problems with US companies becoming monopolists in Europe express grave concern and advocate for state aid to avoid a Scandinavian duopoly at home in the US. Binary nationalist sentiments are not just rooted in mercantilist logic. They are also caused by a fundamental misunderstanding of the composition of US networks. Firstly, Chinese vendors never gained a foothold in a market dominated by US and European suppliers. Hence, the ban of Huawei has had no effect on market concentration. Secondly, the ‘European’ vendors problematised are barely even European. Prior to the advent of 4G, two North American industry champions – Nortel and Lucent – merged with Ericsson and Alcatel respectively to form transatlantic entities. The latter has since been acquired by the Finnish-German conglomerate, Nokia Siemens Networks. These two multinationals are Scandinavian in name only. To this day, Nokia boasts a larger R&D staff inside the US economy than the rest of the US industry (vendors and operators) combined.

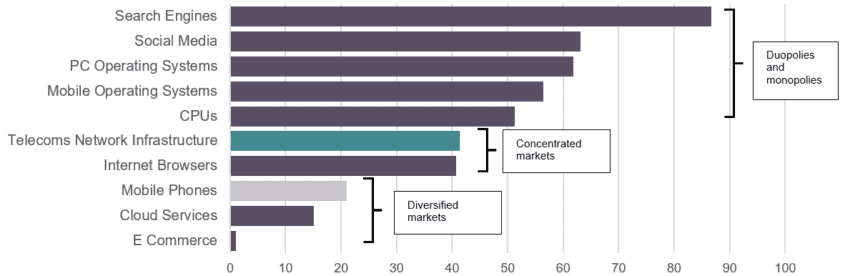

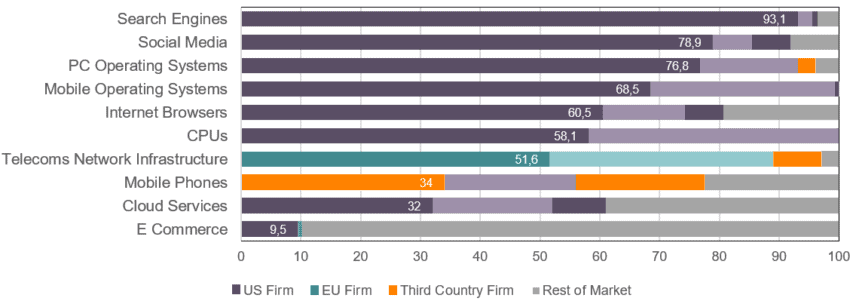

Before advocating for possible alternatives, it is certainly worth contextualising the ‘Ericsson Nokia Duopoly’, by comparing it to the dominance of US ‘Big Tech’ in other critical sectors. Uniquely, Ericsson and Nokia are European-headquartered technology firms that enjoy a majority market share in North America. In the interests of fairness, this analysis compares the role of Big Tech in European markets. Where regional data is unavailable, global markets are cited. Specifically, the following technologies are assessed: telecoms infrastructure, search engines, internet browsers, operating systems, mobile phones, cloud services, e-commerce, CPUs and social media. Market concentration (as indicated by the HHI index), is displayed in Figure 1. Firm-level market structure is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Concentration of Transatlantic Technology Markets

Figure 2: Country of origin in Technology Markets

Source: (Dell’Oro, 2021; Statcounter, 2021; Statista, 2021)[1]

Observing Figure 1, it is clear that technology lends itself to highly concentrated markets. For ‘online platforms’, dynamic competition may well have contrived to create innovative ecosystems, highly efficient competitors and temporary monopolies. Meanwhile, network infrastructure has benefitted from global standardisation and universal interoperability which have yielded massive economies of scale as well as cut-throat competition: The network industry reports profit margins in the single digits at best, or large losses at worst – a stark contrast to US tech giants that routinely generate around 30%. In fact, the entire global industry wide turnover of network equipment is less than the annual profits of just one US platform company.

In this vein, the ‘doddery duopoly’ (as the Economist calls the US 5G market) is fairly unexceptional as indicated by a relatively moderate market concentration index. With that said, the telecoms infrastructure market is only exceptional in its absence of a US-headquartered national champion. In view of Figure 2, it is almost indisputable that the transatlantic policy makers are concerned by national branding rather than the sanctity of competition.

Highly concentrated technology markets have clearly piqued national insecurities in Paris and Berlin, as well as Washington. Nonetheless, if the US – dominant in most tech industries – tries to justify its discriminatory state aid on to EU platform rules, it aims for a transatlantic lose-lose from which there is only one real winner.

[1] For all markets, data is taken from the last available year. Telecoms Network Infrastructure refers to the North American market for 2019 as indicated by Dell’Oro. Search Engines, Social Media, PC Operating Systems, Mobile Operating Systems and Internet Browsers refer to the European market between January and September 2021 as indicated by Statcounter. Mobile Phones refer to the European Market between January and June 2021 as indicated by Statcounter. E-commerce refers to the European market for 2020 as indicated by Statista. CPUs refer to the global market between January and September 2021 as indicated by Statista. Cloud Services refer to the global market between January and March 2021 as indicated by Statista.