Published

Trade in Time of Corona: What’s Next for the EU?

By: Iacopo Monterosa Oscar Guinea Philipp Lamprecht

Subjects: European Union Trade Defence

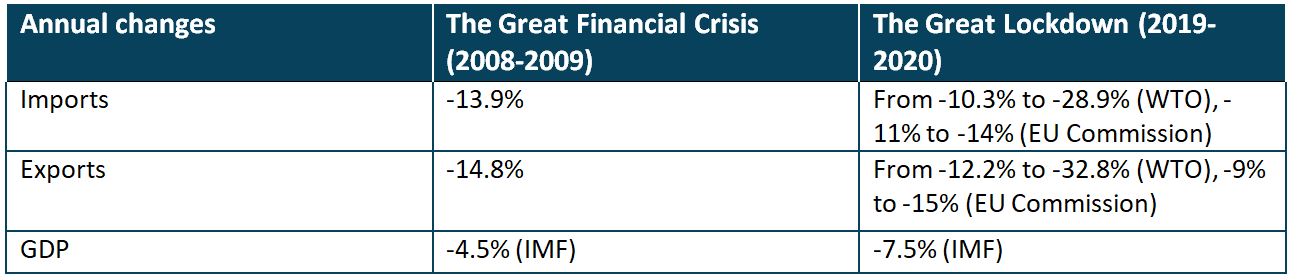

The European Commission updated its trade forecasts for 2020 which followed the WTO’s estimates for this and next year. Both reports agree on a dramatic drop in trade volume due to the economic crisis caused by the pandemic, although the figures vary. In its prediction, the Commission estimates that EU exports will fall between 9% and 15% while imports will decline by 11% to 14% in 2020. Compared to the previous estimates released in April, these predict a greater reduction in trade flows. According to the WTO, the decline in trade for Europe will range from 12% to about 33% and potentially be worse than the one experienced during the great financial crisis of 2008 (see Figure 1 and 2).[1] This drop in trade is accompanied by a pronounced decrease in annual GDP growth, which is predicted to decline by 7.5% in 2020.[2] As trade tends to be more volatile than output, this year’s trade volume might contract more than during the Financial Crisis of 2007–08, when GDP fell by 4.5% and extra-EU exports and imports of goods decreased by about 15% and 14%, respectively.

Figure1. Extra-EU27 Imports and GDP growth, trends and forecasts

Figure 2. Extra-EU27 Exports and GDP growth, trends and forecasts

Table 1: The Great Financial Crisis vis-à-vis The Great Lockdown: EU imports, exports, and GDP[3]

Why is trade so severely impacted in this crisis?

What started as a supply shock, when Chinese workers stayed at home to avoid the spread of the virus, quickly reached other economies that required Chinese imports. As the virus spread, several companies had to close their doors and many more workers had to stay in quarantine. With significant shares of global manufacturing in shutdown, trade in goods experienced a severe downturn, especially pronounced in sectors, such as the electronic and automotive industry, that rely on complex Global Value Chains (GVCs). This was confirmed by the fall in the EU industrial production which dropped by 11.8% in March and EU imports which declined by 23.5% in April. Additionally, many services were directly hit by Covid-19, due to the transport and travel restrictions and the closure of retail and hospitality activities.

The demand shock has been considerable too. Uncertainty has peaked and consumers and firms have postponed many purchase decisions, resulting in job losses and falls in household’s income. Whilst the great financial crisis started with the fall of Lehman brothers, morphed into an economic recession, and led to a public debt crisis; Covid-19 is taking us straight into an economic downturn. Like in previous recessions, the magnitude of the economic recovery will depend on the effectiveness of policies that governments pursue.

Trade is not the problem but part of the solution

If Covid-19 were to be a tariff, it would be equivalent to a 3.4% global tariff on trade. It may not sound much but it is significant when you realise that more than half of all EU import tariffs are less than 2%. Similarly, 48% of Japan and 39% of US tariff lines are duty-free. Many European exporters will face the Covid-19 tariff, which will impact its competitiveness vis-à-vis other exporters and domestic suppliers. This is important because Europe’s exporting companies are crucial for its economic recovery. In 2017, 36 million jobs were dependent on EU exports to the world. Moreover, 20 million jobs beyond the EU were supported by EU exports, thanks to EU firms participating in GVCs.

As we’ve seen in the first quarter of 2020, without well-functioning supply chains, countries’ production capacity can suffer from prolonged disruptions, affecting millions of workers and companies. Trade is a two-way street: one countries’ imports are other countries’ exports. As such, GVCs are fundamental to support the global economic recovery as companies can tap into other countries’ demand, selling the products that they are best at producing.

Despite Europe’s reliance on exports and on GVCs, some European political leaders are looking inwards, highlighting the dangers of relying on these production networks, leading to talks of “de-globalisation”.

In this context, DG Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan is developing a new trade strategy for the EU27. Recently, he called for “Open Strategic Autonomy” which he defines as “a coherent set of policies that achieve the right balance between a Europe that is open for business and a Europe that protects its people and companies.” Similarly, DG Trade Director-General Sabine Weyand points to the importance of having a “much more sophisticated discussion on the resilience of supply chains” and calls for a detailed analysis to be conducted together with business to analyse where is “space and need for public intervention”.

Finding this new balance and addressing these challenges does not need to be an exercise of closing Europe’s drawbridge. First, the EU should continue deepening its bilateral trade relationships if it wants to diversify its suppliers at the lowest possible cost. Second, as the EU’s digital economy grows, digital trade must follow. The new trade strategy should offer pathways for the EU to work with other trade partners to establish market-access commitments and better rules internationally, for example addressing the growing challenge of cybertheft.

Finally, timing is of the essence more than ever. If any new strategic balance or detailed analysis of supply chain resilience is to be established, it needs to result in concrete actions soon. As illustrated by the forecasts, European companies and their trading partners cannot afford to wait until the end of the year.

[1] WTO projections on trade flows vary not only with respect to the drop in trade and the length of the crisis but also in relation to the magnitude of the economic recovery, which is full in the optimistic scenario and incomplete in the pessimistic case. Trade data, in volumes, is retrieved from the International Trade statistics available on Eurostat.

[2] Annual real GDP growth figures for the Euro area are available from the IMF here and are aligned with the estimates published by the European Commission, available here. For 2021, Euro Area’s real GDP is projected to grow by 4.7% per cent.

[3] Imports and Exports figures for EU28 countries in the Great Financial Crisis are based on the authors’ calculations using International Trade statistics available on Eurostat. These are aligned with WTO data available here.

One response to “Trade in Time of Corona: What’s Next for the EU?”