Published

The Free Flow of Non-Personal Data

Subjects: Digital Economy EU Single Market Five Freedoms Services

Earlier this month MEPs voted to support the final text on the free flow of non-personal data across the European Union (EU). A vast majority of the European Parliament voted in favour of this new regulation.

This is good news. The regulation removes obstacles to the free movement of non-personal data. It reduces the number and range of data localization restrictions, and improves the conditions under which regulators, consumers and service providers use data. Non-personal data is often used in production of goods and when thinking of the 4th Industrial Revolution, it will be an essential factor for many industries.

The biggest winner of this regulation is the EU’s economy. Digital flows play a more and more important role in Europe’s economy. Besides the goods and services EU members trade with each other, the free flow of data will further contribute to a more competitive European economy, as a so-called “Fifth” freedom.

That is because digital trade generally, and the free flow of data particularly, has become an essential factor in many other industries and sectors to run operations smoothly. The use of digital and other data services such as cloud computing, data processing services and computer and ICT services by many other industries and sectors makes the EU economy much more productive.

The crucial point, therefore, is that policy makers should facilitate the provision of these ICT services as much as possible. Reducing burdensome barriers such as the regulation the European Parliament approved will do that job. But, much more is needed, as there are still many other digital barriers remaining.

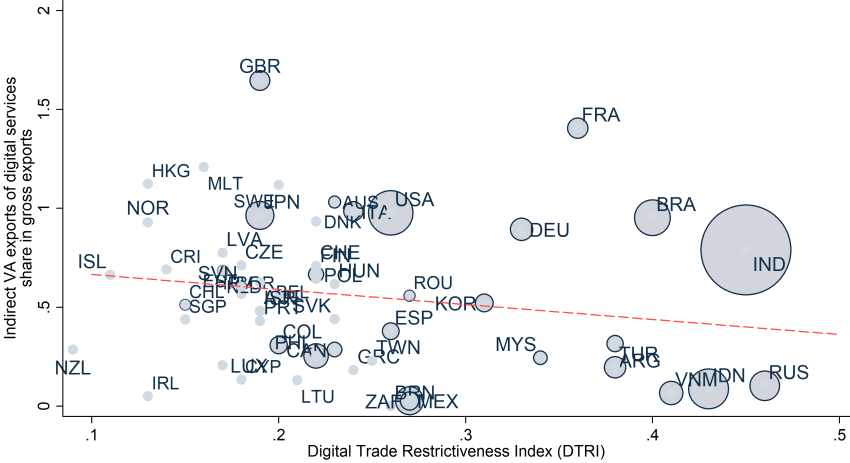

To illustrate this point, Figure 1 sets out that story. The figure displays on the vertical axis the extent to which countries use digital and data services in other industries and sectors and exports these services indirectly to other countries, after they have been embedded as inputs into other products and services. A higher level on this indicator measures a greater level of this indirect digital services export.

Figure 1: Indirect digital services trade and Digital Trade Restrictiveness Index (DTRI)

Source: OECD; ECIPE; Ferracane et al. (2018)

The horizontal axis shows the Digital Trade Restrictiveness Index, which is ECIPE’s new index that measures the level of restrictions in digital trade with regards to more than 100 different policy categories, varying from investment restrictions in digital sectors to data localization requirements with regards to the cross-border movement of data. The index varies from 0 (least restricted) to 1 (virtually closed).

The figure shows a downward sloping trend. That means that countries that have higher levels of all sorts of trade restrictions, and therefore less free trade policies regarding digital trade, show lower levels of digital services being integrated and exported through other industries and sectors. As such, high digital trade restrictions hold back the potential productivity bang that the EU is waiting for.

Some EU countries such as Germany and France already have a high share of digital services indirectly traded. Yet their level of restrictions is still relatively high. This does not mean that things are fine. On the contrary, they could do so much more to boost the EU’s digital economy and trade competitiveness given their current state of digital trade restrictions across the entire field.

Examples include regulatory restrictions in e-commerce, investment restrictions in digital sectors or intermediate liability measures that restrict the operations of platforms. Therefore, the removal of data localization restrictions is an important step as it improves trade and productivity, but the horizontal axis tells us that there is a whole lot more that affect the EU’s trade and competitiveness.