Published

The European Productivity Slowdown in a Global Context

Subjects: European Union

The decline in EU competitiveness is certain to be a key issue for European policymakers over the next five years. This concern is well-founded. The EU’s share of global GDP has shrunk from over a quarter in 1980 to just 17 percent today. A significant factor in this decline is slowing productivity growth. As highlighted in an ECIPE Policy Brief published last month, the EU lags behind the US in key areas such innovation, intangible capital, and attractiveness to investors.

In addition, enhancing productivity is crucial for the EU to achieve its social and environmental objectives. Productivity growth is a key driver of wage increases and a tool to face the challenges posed by an ageing society. Furthermore, improved economic efficiency is indispensable to achieve the energy transition and mitigate the costs of climate change for businesses and society at large.

This blog extends the transatlantic comparison of productivity from our previous paper to include other developed economies like the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, and Canada.

Sluggish Productivity Growth and Technological Progress

Advanced economies are experiencing a dual challenge to productivity growth. The first concerns the rate of output per hour worked, also known as labour productivity. The second challenge refers to the slowing pace of technological advancement, as measured by the change in total factor productivity (TFP).

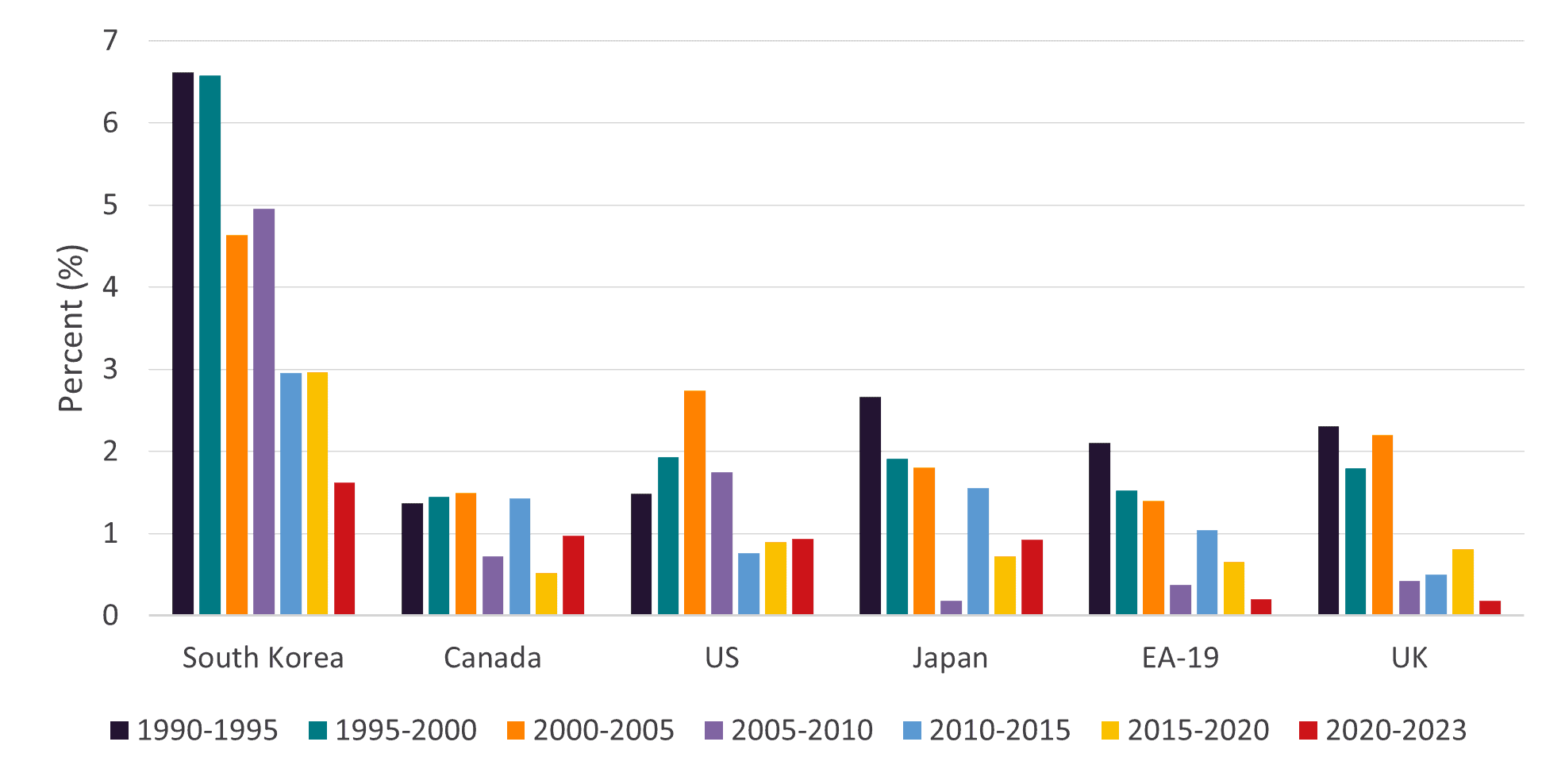

Figure 1 reveals an average decline of 1.9 percentage points in labour productivity growth across the six regions from 1990 to 2023. Europe experienced the sharpest slowdown, with growth in the Euro Area and the UK falling by more than a factor of ten. South Korea stands out: its high pre-2000 productivity stemmed from three decades of successful export-oriented policies, rapid industrialisation and catch-up growth.

Figure 1: Labour productivity growth (GDP per hour worked, constant prices; 1990-2023)

Source: The Conference Board.

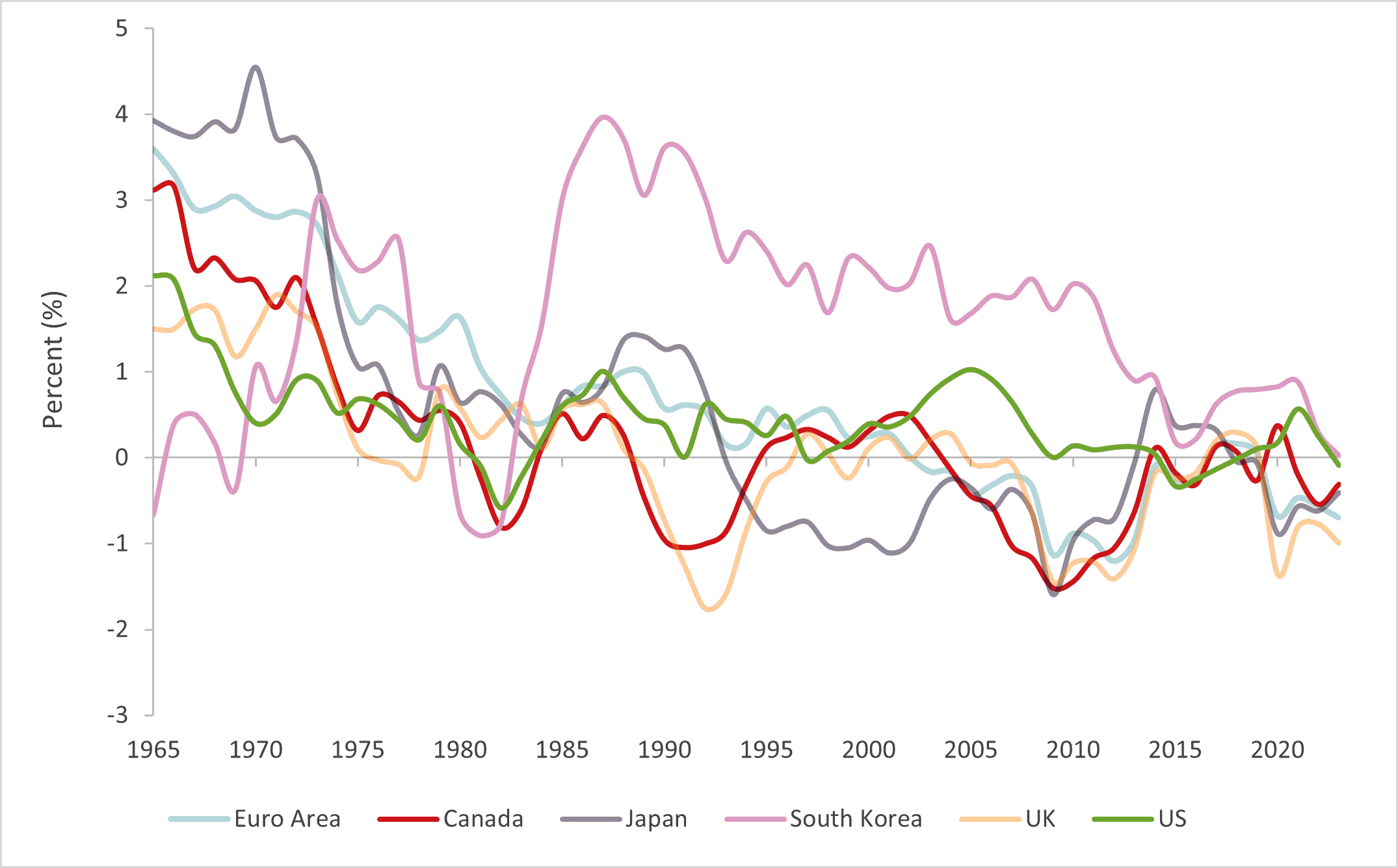

TFP growth shows a similar pattern. TFP measures the unexplained growth in an economy’s output that cannot be attributed to increases in labour or capital inputs. Innovation, technological change and management practices are determining factors behind TPF growth.

Taking a sixty-year perspective from 1965 to 2023, Figure 2 shows an almost continuous and generalised decline in TFP growth across regions. The Euro Area rate of technological progress plummeted from 2.5 pre-1980 to mostly negative levels since the Global Financial Crisis, mirroring trends in Canada, the UK, and Japan. This trend has two notable exceptions: South Korea and the US. South Korea experienced a surge in TFP growth during the 1980s fuelled by rapid industrialisation, but has since converged to the other countries’ growth rates. The US, in contrast, exhibits a more moderate decline in TFP growth, maintaining positive levels for longer periods than most other countries except South Korea.

Figure 2: TFP growth (5-year averages; 1965-2023)

Source: The Conference Board.

Trailing in R&D spending and patent application

Innovation is another area where the EU has fallen behind, not just compared to the US but also relative to other economies.

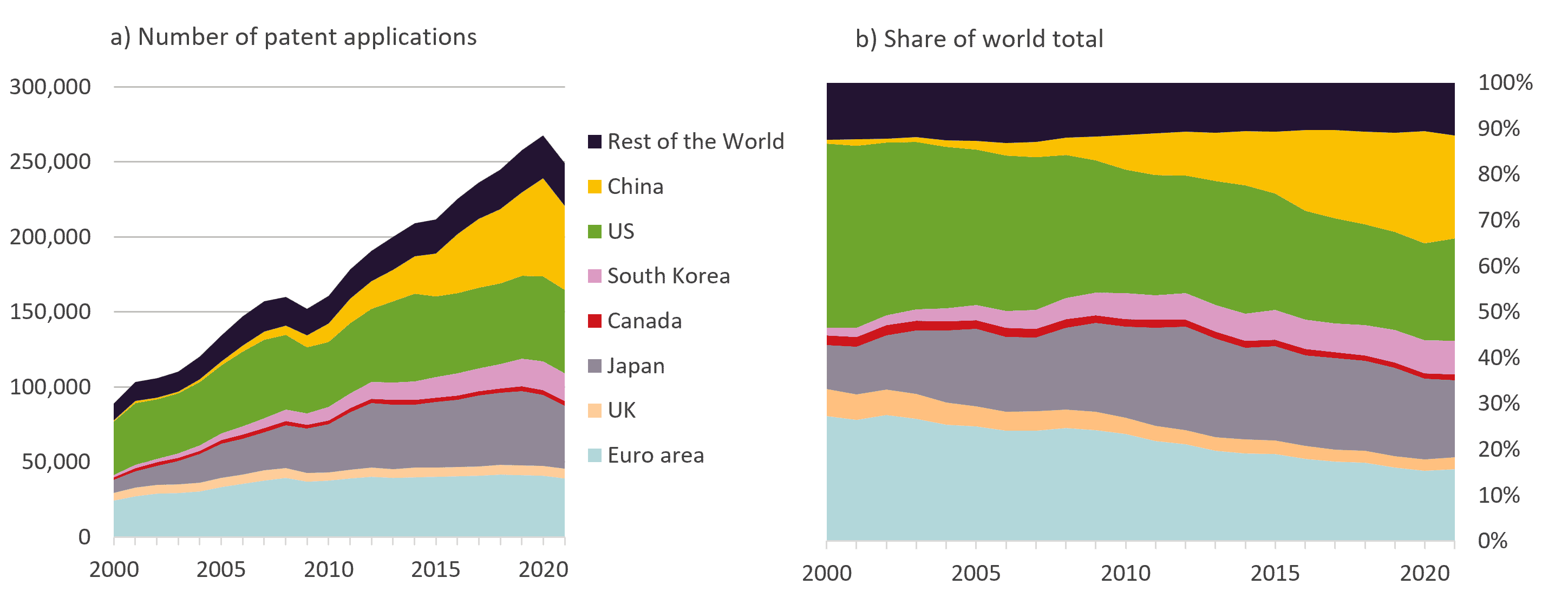

Figure 3 shows that stark decline in European innovation. Once the second-most innovative region behind the US, with 27 percent of global patent applications in 2000, the Euro Area has fallen to fourth place by 2021, holding only 15.2 percent. This gap has been filled by surging innovation in Japan (up 7.2 percentage points), Korea (up 5.8 percentage points), and particularly China (up 21.7 percentage points). Though not all patents have equal quality and Europe still has excellent research centres, the ability of firms to issue patents determines their ability to compete in global markets and remain profitable. Losing ground in terms of innovation output means a future economic landscape that contains fewer relevant European firms and products.

Figure 3: Total patent applications by region (2000-2021)

Source: Authors’ calculations based on OECD data. Note: Numbers refer to patent applications filed under the PCT, by inventors’ address of residence and date of application.

However, focusing solely on total patent applications provides an incomplete picture of the Eurozone’s innovation capacity. Two additional factors need attention: business expenditure on R&D (BERD) and the sectors where Europe concentrates its innovation efforts.

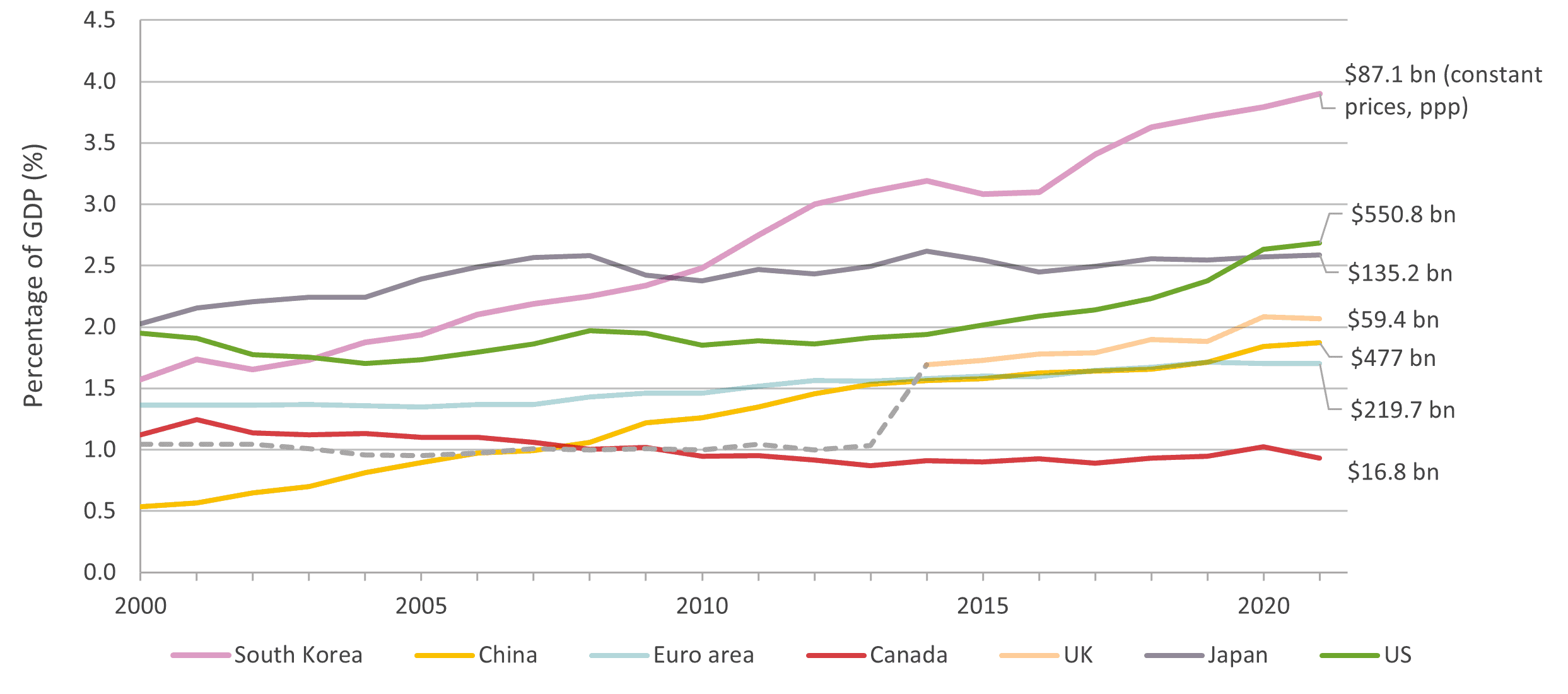

First, the Euro Area underperforms in terms of business R&D spending relative to its economic size. While BERD has grown from 1.36 percent of GDP at the turn of the century to 1.7 percent in 2021 ($219.7 billion in constant PPP terms), as shown in Figure 4, this increase pales in comparison to the efforts of South Korea (+2.33 percentage points) and China, whose BERD skyrocketed from less than $24 billion to a staggering $477 billion in two decades. Furthermore, European public R&D spending, at 0.57 percent of GDP, does not compensate for the shortfall in business investment but remains below the 0.68 percent of GDP from the OECD countries considered here.

Figure 4: Business expenditure on R&D 2000-2021 (BERD, percentage of GDP)

Source: OECD-MSTI. Note: Due to data availability issues, the euro area does not include Malta, Cyprus, and Croatia. Data for the UK prior to 2014 is indicative due to a methodological break.

Second, the research areas in the EU have barely changed over the last decades. A recent report on EU innovation policy highlights a concerning trend: industrial R&D suffers from a bias towards established, “mid-tech” sectors like automotive parts. This focus is unsurprising considering the prominence of the transport industry in countries such as Germany, France, and Italy. In contrast, other advanced economies, including the US, have increasingly supplemented mid-tech R&D with high-tech efforts in sectors like software, computer electronics, and biotechnologies. These high-tech innovations offer broader applicability across various industries, unlike car-specific patents that remain largely confined to the transportation sector.

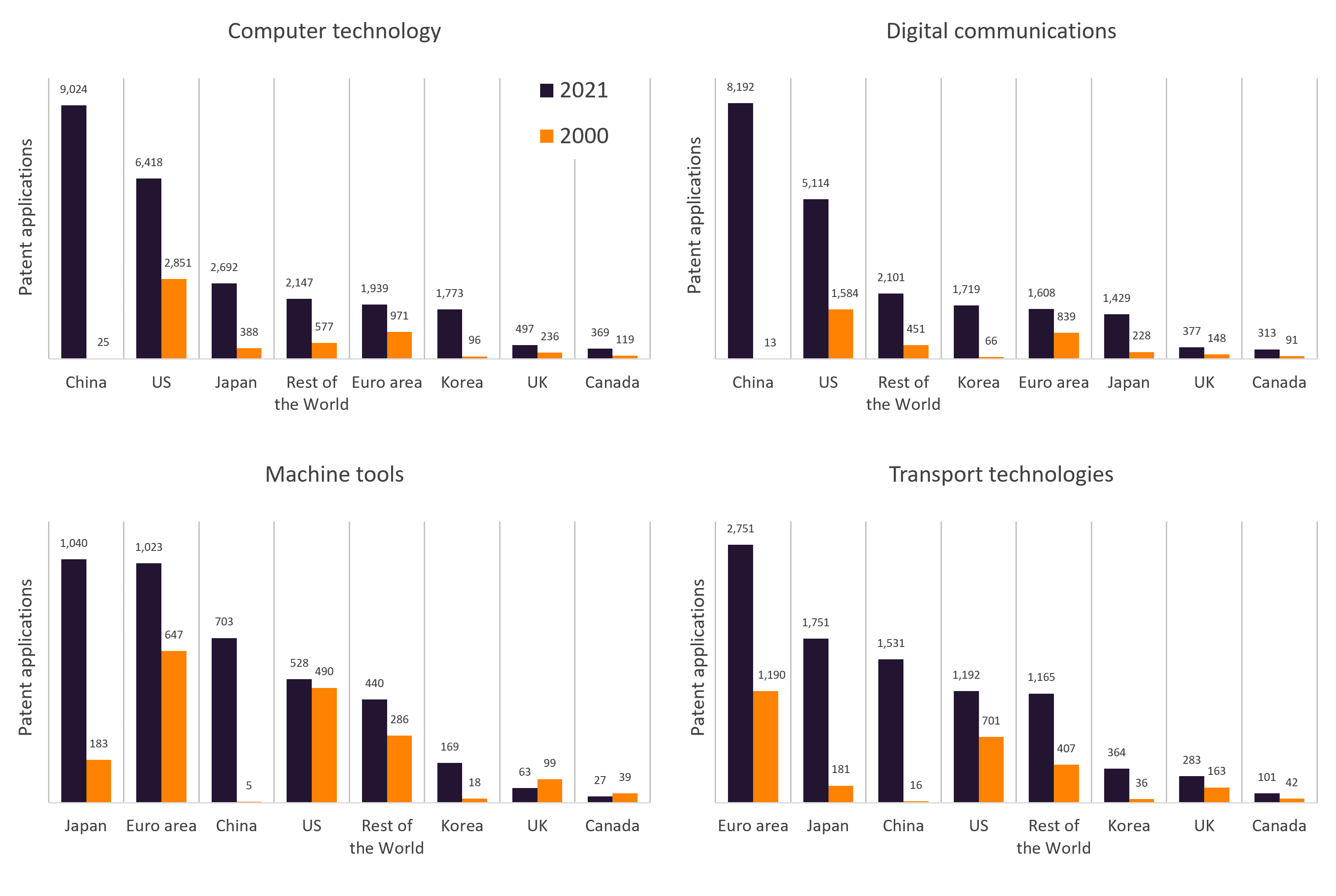

This trend is evident in Figure 5, which shows patent applications across four technologies between 2000 and 2021. While the EU remains a leader in traditional sectors like machine tools and transportation, it lags behind the US, China, Japan, and Korea in computers and digital communication technologies. This is a significant reversal from two decades ago, when the Euro Area held the second-place spot for these very technologies.

Figure 5: Patent applications for selected technologies (WIPO technology categories)

Source: OECD-REGPAT. Note: Numbers refer to patent applications filed under the PCT, by inventors’ address of residence and date of application.

However, Europe’s technological decline is not inevitable. By implementing the right policies, the EU can reverse this trend and reposition itself at the innovation frontier. To echo French President Macron’s vision of the EU as a major power in innovation and research, the EU should increase public and private R&D spending and set the right policies for EU companies to lead in new technologies.

This goal will not be reached by just brute budgetary force. Europe’s technological success hinges on fostering companies at the technological forefront, able to develop and applying the latest technologies. To achieve this, the EU must become a magnet for these companies, both as a birthplace and as a destination. Horizontal industrial policies hold the key. These include establishing a stable and predictable legal framework, investing in R&D, human capital, and both tangible and intangible assets, and facilitating the integration of capital, goods, and services within the EU. By implementing such measures, the EU can propel itself towards global leadership in innovation and productivity.