Published

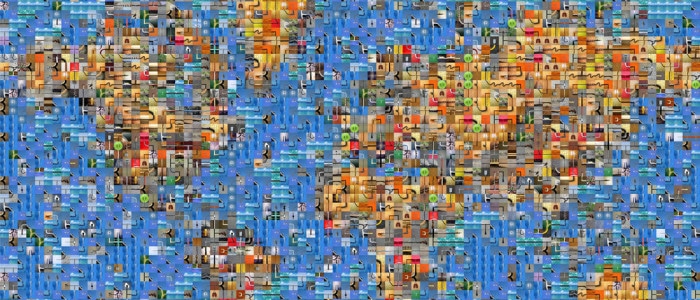

Re-Globalisation

Subjects: New Globalisation WTO and Globalisation

Globalisation is in trouble. Ever since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, global trade has been unable to return to its preceding upward trend. Rising protectionism, falling efficiency gains from supply chains established by multinationals in the 1990s, and the lack of real trade liberalization in the last ten years, are the predominant factors causing globalisation’s bad shape. Meanwhile, the Covid pandemic has now given global trade a full blow. That, moreover, has spurred many countries around the world to apply new policy restrictions in trade.

This has led experts to declare that globalisation is in retreat. Globalisation, it is argued, has disembarked on a downward spiral that is only taking its natural course, as it forms part of a long-term cyclical process that began after the GFC. Der Spiegel, for instance, a quality news magazine in Germany, assesses alarmingly that this is just the beginning as we are moving away from world trade integration1 . In short, we are living in times of de-globalisation.

These experts are wrong, for that globalisation is not in retreat, but changing. In fact, the very nature of globalisation is converting into something more invisible and digital, based on ideas and data, driven by the internet and other digital technologies. For example, since 2010, trade in technology ideas has grown faster than trade in both goods and services. After the GFC, trade in R&D, ICT, and information sectors, has outpaced trade in the rest of the services economy. And over the last five years, international knowledge diffusion, measuring flows of ideas crossing borders, has increased by a factor of more than 1.3. Meanwhile, international data flows are still rising exponentially.

These facts portray a different reality that is also happening in the global economy. This reality is much more optimistic, counterbalances the routine thought that global trade must suffer at some point in time, and uncovers that globalisation is in fact soldering on – albeit in different ways. De-globalizers share the belief that world trade follows a self-propelling path in which borders are re-erected again. Re-globalizers, instead, share the perception that globalisation has the ability to reinvent itself thanks to open borders.

What can explain the two very different perspectives on globalisation? And what is it that de-globalizers fail to see in the eyes of re-globalizers? The answer is, in large part, technological change. To be fair, trade in goods, which forms the focal point for the many de-globalisation analyses, is in a terrible state. Trade in goods has expanded much slower than GDP for a long time and experienced a free fall during the Covid outbreak. And even though the imports and exports of goods has bounced back in recent months, it might never return to the pace it once had before.

But this narrow concept of global flows precisely points out de-globalizers’ weakest point: over the years, globalisation has become much more than just trade in goods and commodities. Global flows now include items ranging from the exchange of many new services, the internet and online platforms, to ideas embodied in intellectual property, online research collaborations, and the flow of data crossing borders multiple times a day, such as cloud computing.

These are new international flows people were unable to imagine just a decade ago. They now have become part of our daily economic life, and along with that, of international exchange, too. For instance, US exports of ideas embodied in intellectual property has almost doubled between 2005 and 2018, from 64 bln to 119 bln, representing a share of around 5 percent of total US goods and services. In Germany, the exports of ideas have more than quadrupled since 2005. These flows are often difficult to detect as they are intangible and invisible, and therefore difficult to measure, but in no way less important as drivers of globalisation in the world economy today.

The Covid crisis will unlikely stop this surge in renewed globalisation. True, global trade fell sharply in April and May last year, making up for steep losses. MNE managers report that during Covid, supply chain reliability is one of the major factors being most negatively hit. And services such as tourism and transport have experienced a massive downfall. And yet, it is also true that during the pandemic ICT services have expanded steadily, that data flows exhibited a 50 percent increase in many countries (and is likely to continue at a higher speed after the pandemic), and that IP flows has only suffered a marginal decline in some countries. That echoes experiences from the past: after the GFC, it was digital-intense services trade which was rising faster than any other goods or services flow. If anything, the growth of this newly arising trade is likely to stay with us after Covid.

That said, new globalisation should not be taken for granted. As much as protectionist measures have been on the rise in formal trade, new trade also suffers from rising trade restrictions. Countries such as China, Turkey and Russia are practically sealed to the outside world when it comes to the cross-border flow of data over the internet. In many countries, online platforms operate under strict censorship conditions. Similarly, many countries apply restrictions on intellectual property rights (IPRs) and even require mandatory disclosure of business trade secrets such as algorithms and source codes. And free markets in telecommunication services, the infrastructure on which new trade thrives, is still an illusion in many parts of the world.

A free and unrestricted internet in particular plays a significant role in the expansion of idea and data-based trade. The Freedom House assesses countries from all regions of the world on the basis of their internet status and separates them into a free and unfree internet. Using their classification, trade numbers tell that the group of countries classified as having a free internet are the ones where the share of IP flows (ideas traded across borders) is three to four times larger than countries without a free internet. That number shoots up to eight times for R&D services.

Overall, globalisation in its new incarnation is not in retreat but continuing its march forward, albeit differently. French president Macron is right to say that Covid will change the nature of globalisation, but that change has been going on for years. The new nature of globalisation will cover a different type of trade, powered by ideas, data, research, and technology. Countries should therefore prepare for these new global flows that are coming.

1 https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/future-of-our-global-economy-the-beginning-of-de-globalisation-a-126a60d7-5d19-4d86-ae65-7042ca8ad73a

Are the data about R&D really reflecting that or can this category be used by MNEs to shift profits

That’s a great question, Nicolas. I would say that this is not so much the case with R&D services, but may be more the case in other services categories, for instance in NAICS category of “Management of Companies and Enterprises”. For the trade data used in this blog that category would show up in a different sector grouping, and not in R&D.

Dear Erik,

Thanks for your response.

Best,