Published

Preparing for COVID-20

By: Oscar Guinea

Subjects: European Union WTO and Globalisation

If there were to be another pandemic, what would you have done differently?

This question should be at the front of any policy-maker. Covid-19 has been costly but some countries have coped better than others. In the EU, Spanish GDP fell by 22.1% while Finnish GDP dropped by 5.2%. As a comparison, South Korea GDP, a country which suffered previously from SARS, went down by just 2.8%.

Therefore, countries can and should learn from Covid-19. But which are the lessons?

In a new paper published by ECIPE, we look at the lessons that the EU should learn from Covid-19.

Lesson 1: Countries have become more open not less

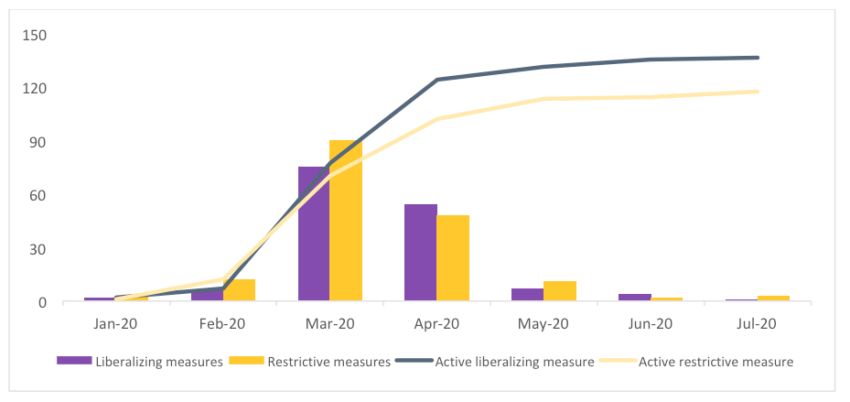

Globalisation has been good for countries facing the challenge of Covid-19. And despite the prevailing view, most countries have actively opened their markets. Not just by lowering tariffs but also by amending their national regulations to facilitate imports. It’s also true that many countries made exports of medical goods more difficult. However, many of these export restrictions backfired and were rolled back. Overall, the number of trade liberalizing measures that stayed in place exceeded the total number of restrictive measures.

Figure 1: Number of Trade Measures Adopted from January to July 2020

The painful truth about unexpected shocks like Covid-19 is that countries cannot plan for them in the same way as they plan their infrastructure projects or annual spending on education. The best we can do to prepare for this kind of shocks is to build buffers and flexibility in our economies and systems to better cope with these shocks once they come.

Lesson 2: Self-sufficiency isn’t an option

No country is too big or too developed to produce all the medical goods necessary to face a pandemic. Not even China, one of the main producers of face masks, could meet its own demand and had to import a large number of face masks at the beginning of the crisis. Moreover, any step towards self-sufficiency will be costly. Imagine if every country would have to build the factories to replicate the value chain of the 621 components of a ventilator in their national soil.

Yet, global value chains have delivered. Despite all the difficulties, businesses have been successful at increasing production of personal protective equipment in a very short notice. As an example, the EU bought 40% of its Covid-19 test kits and diagnostic reagents from outside the EU and imports of thermometers between January and April of 2020 grew by 42% compared to the same period of 2019.

Lesson 3: Re-shoring isn’t the right strategy

If import diversification is the goal to increase the resilience of EU’s imports against a future crisis, the EU shouldn’t concentrate more production within the EU. An unpredictable event like a pandemic is more likely to hit EU countries simultaneously and the economic consequences of this shock would be quickly transmitted across EU economies. The answer to a symmetric shock, therefore, does not need to be to concentrate more production within the EU itself. That is the opposite of diversification.

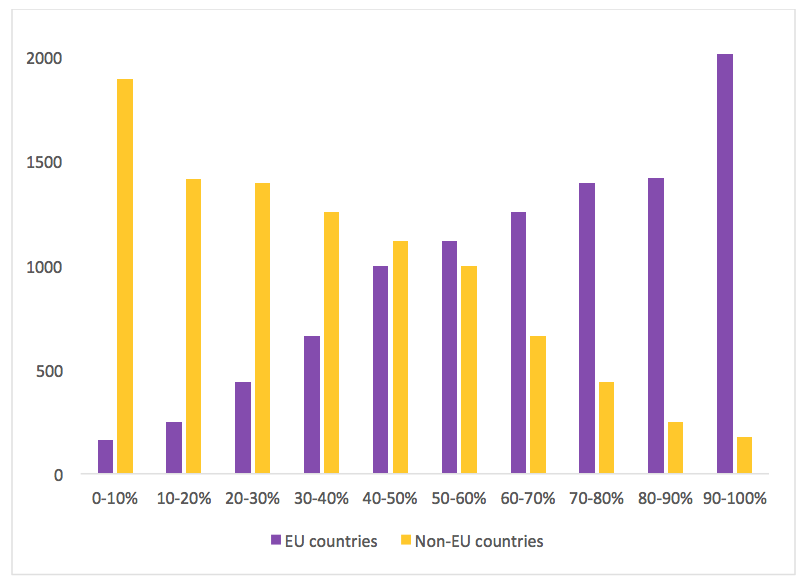

Imports from abroad make Europe more resilient. In our new ECIPE paper, we calculated that intra-EU imports already account for more than 80% of all EU imports in more than 3,000 imported products. In comparison, there were only 400 products that were imported from non-EU countries where these non-EU countries capture a market share larger than 80% of all EU imports.

Figure 2: Number of Imported Products into the EU by Market Share of EU and Non-EU Countries (2019) Source: COMEXT Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Source: COMEXT Eurostat, authors’ calculations.

Market concentration is an important metric to understand a country dependency from an importer. Those countries where a few importers supply a large market share are also the ones which are more exposed to shocks impacting their largest suppliers of imports. Our paper shows that imports from outside the EU lowers the degree of market concentration that EU countries have on each other, increasing the diversification of imports and making the EU less vulnerable to symmetric shocks. For example, in France, the share of the top four EU suppliers of imports sourced within the single market was equal to 79%, whilst after accounting for imports coming from outside the EU, the market share of the top four suppliers fell to 65%.

But not all products are equally important when a crisis hit. Our paper looks at EU’s vulnerability on essential products based on a list of 118 Covid-19 medical supplies published by Eurostat. The data shows that there was not a single Covid-19 related product that was solely imported from one EU or non-EU country. Furthermore, there was not a single product for which the EU has a market share lower than 20%. This is important as it indicates that the EU has the know-how to produce all the Covid-19 related medical products. On average, Covid-19 goods were supplied from 46 countries.

In our paper, we look in detail at these three lessons and provide new analysis of EU’s dependency on foreign countries including China, the US, and the UK. We conclude that while import diversification is a reasonable strategy for some goods, re-shoring manufacturing back to the EU isn’t the right policy.

The new ECIPE paper Globalisation Comes to the Rescue: How Dependency Makes Us More Resilient is available here.

One response to “Preparing for COVID-20”