Published

H20 Back in the Chinese Market: Washington’s Calculated Adjustment

By: Guest Author

Subjects: Digital Economy Far-East North-America

By Hao Wu, research assistant at ECIPE

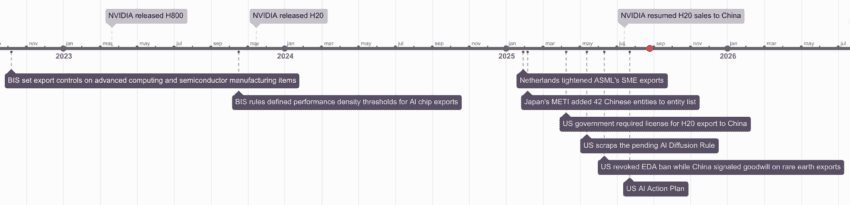

Timeline

Made with time.graphics

NVIDIA’s H20 GPU resumed sales to China as the company announced Washington’s decision on July 15. The unexpected move has revived memories of past export controls of NVIDIA H100 when the US CHIPS Act sought to restrict China’s access to cutting-edge chips. While the H20 had been the only AI accelerator designed to legally enter the Chinese market since the BIS rules in October 2023, it soon became subject to export bans amid intensifying US-China trade frictions until recently being lifted in mid-July. The same applies to AMD’s MI308, with the company confirming its export license application is under review and awaiting for final approval after months of paralysis under the April semiconductor rules. Their reinstatements signal not so much a strategic reversal as a transactional bargain: Washington is willing to grant limited access in exchange for leverage, even in the meantime maintaining deliberate downgrading to slow China’s pace. Yet while the current office remains tough talks, the episode seems to mark a tangible sign of easing AI hardware tensions since the Biden administration unveiled its latest round of export controls this spring.

The H20 is far from a flagship. It is a deliberately stripped-down version of NVIDIA’s H100 GPU, designed in response to US export rules. Built on the same Hopper architecture released in 2022, the H20 carries just a fraction of the computation capacity. This sharp downgrade is not accidental: the 2023 BIS rules set strict “performance density (PD)” thresholds, a formula balancing computability against chip size. The logic is straightforward: delivering high computing power in a small area means heavy reliance on advanced manufacturing process. Washington capped this ratio to prevent China from reaching products built on cutting-edge nodes. In practice, the H20 stays below the limit and is to bypass a full Commerce Department license process to be sold to China. It also continues a clear pattern of NVIDIA’s earlier “only for China” products: the tailored H800 chip in 2024 and earlier A800 were also similarly customised, less powerful versions of the H100 and former A100 models, built specifically to comply with Washington’s rules.

The mid-July easing of restrictions was not limited to AI accelerators. The upstream side of semiconductor manufacturing was also covered in the broader policy recalibration, where Washington relaxed restrictions on exporting the Electronic Design Automation (EDA) to China. These tools, which had previously been placed on the export control list, are essential for designing advanced process chips. Allowing the EDA access reflects a strategic calculation: unlike lithography machines or wafer fabrication equipment, the EDA do not directly enable China to mass-produce cutting-edge chips, but they do keep its design ecosystem tethered to U.S. suppliers. By loosening the constraint, Washington grants Chinese firms a little more breathing room to sustain design capacity, while still preserving tight curbs on manufacturing equipment and advanced lithography.

The timing of the policy shift is telling. The US-China trade talks in June, the first concrete results of negotiations since the Trump-era tariff escalations, produced quiet but significant concessions. Beijing signalled plausible goodwill on rare earth exports, while simultaneously approving Synopsys’s acquisition of an EDA asset in China, a nod to U.S. concerns over intellectual property and market access. Although officials claimed it a delaying tactic to preserve China’s dependence on US technology, Washington’s chip easing in mid-July appears less a unilateral adjustment than part of a reciprocal exchange. The H20 and MI308 carve-outs fit neatly into this pattern: not a strategic reversal of U.S. semiconductor policy, but a negotiated bargain in which each side traded leverage points, rare earths and market access on China’s part, limited hardware access on Washington’s with NVIDIA holding the chips.

The unexpected rise of DeepSeek challenged Washington’s assumption that constrained hardware conditions alone could hinder China’s AI progress. Despite tightened controls, this large language model (LLM) from China showed that algorithmic innovation will not be crippled by blunt compute caps. Promoted domestically as a “software-first” response to U.S. restrictions, DeepSeek was trained and deployed on less performative clusters. And H20 would be a perfect match for this context. In practice, despite the chip’s throttled compute, its ample memory and generous bandwidth proved ideal for large-scale, low-precision inference workloads. The model likely added the pressure as Washington recalibrated the balance in its April decision to ban H20.

We see more active corporate moves as NVIDIA is not leaving the field to geopolitics. CEO Jensen Huang’s recent trip to Beijing included a high-profile meeting with Xiaomi’s Lei Jun, whose empire spans smartphones and EVs, following an earlier audience with Vice Premier He Lifeng during the height of the April H20 ban. Corporate diplomacy is now intertwined with navigating U.S. export controls: by engaging high-level relationships with China, NVIDIA positions itself to preserve market access even as policy shifts threaten to shut it out. The corporate strategy is twofold: provide compliant hardware, and reassure Chinese partners of continued engagement. In doing so, the company seeks to slow the loss of Chinese customers toward domestic alternatives, a risk amplified by China’s accelerating drive for “indigenous substitution” across its AI stack.

The Chinese market offers NVIDIA both opportunity and competition. Despite H20’s significant performance downgrade, it remains attractive thanks to NVIDIA’s robust CUDA ecosystem for developers and unmatched compute efficiency. With a decade of technological accumulation and over 4 million developers worldwide, CUDA has created a de facto ecosystem lock-in and strong market demand. It is therefore no surprising that the H20 remains difficult to replace in the short term, albeit with curtailed computability.

On the other hand, Chinese players are gaining ground. One month before NVIDIA ordered 300,000 H20 units from TSMC at the end of July, Chinese telecom giant Huawei introduced the Ascend 910C, a 7nm-process based chip designed for high performance computing (HPC) including large-model training and inference. Though it falls short of NVIDIA’s absolute capabilities (60–80% of H100’s performance on inference), Huawei employs dual-chip packaging techniques to boost compute output. Its CloudMatrix 384 built interconnects 384 units of Ascend 910C, delivering double the performance of NVIDIA’s competitor.

But it does not mean a triumph; the CUDA ecosystem remains unmatched in breadth and maturity. Huawei’s CANN architecture, while competitive in specific applications like medical AI, lacks CUDA’s breadth. Thus, even as Huawei gains in hardware, NVIDIA retains a critical edge in software infrastructure.

The hardware–software gap shapes the competitive timeline: short term prospects indicate China’s continued AI momentum, yet remained far behind the US where private AI investments reached $109 billion, twelve times China’s level. Without a robust software ecosystem on par with NVIDIA’s CUDA, Chinese hardware advances may struggle to translate into sustained AI leadership.

In this light, Washington’s greenlight for the H20 is a calculated bait, the US approach seeks for a dynamic balance between absolute denial and managed risk. Beyond easing policy, it appears designed to selectively target Huawei, curbing the company’s ability to capitalise on domestic market demand and policy support. At the same time, it could serve to limit Huawei’s expansion in “blue ocean” markets beyond China: emerging economies in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa express growing demand for affordable AI compute, and competition for global AI compute leadership is heating up.

In mid-May, Washington abruptly scrapped the pending “AI Diffusion Rule,” which would have capped aggregate AI chip exports to foreign buyers. The reversal highlighted the tension between sustaining US AI hardware lead and avoiding self-inflicted wounds to its semiconductor industry. Even as the US pursues compute-driven AI development and large-scale deployment, aggressive policy swings have inevitably weighed on commercial players. As such, stable policy is essential for NVIDIA: the H20’s approval will not bring immediate shipments in practice. The H20 will have a limited elasticity in the near term, as restarting the supply chain takes time, especially with heavy order backlogs at TSMC limiting flexibility.

While Washington keeps updating restrictive measures, blocking China’s access to advanced chips has long been an unchanged goal. National policy will continue to drive domestic semiconductor R&D and manufacturing, expand data centre and energy supplement. The US is yearning for absolute AI compute advantage when it calls for secure global AI deployment: the newly released AI Action Plan on July 23 doubles down on securing allied coordination in AI hardware, software, application, and security, integrating AI governance into national security planning. The H20 reprieve sits within this balancing act: a narrow, transactional loosening paired with heightened vigilance on technology transfer.

Allies face a sanctions dilemma, caught in the crossfire of US strategy shifts. In January, the Netherlands tightened semiconductor manufacturing equipment (SME) export rules, following its 2023 decision to restrict ASML’s DUV and EUV lithography sales to China. In February, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) added 42 Chinese entities to its export control entity list. These steps weren’t coincidental: decisions were made when Trump’s officials reportedly met with Japanese and Dutch counterparts to push for expanded curbs on Chinese access to advanced technology. While allies maintain formal control over their policies, the strategic alignment with Washington is unmistakable.

But now as Washington relaxed H20 rules, allies face a credibility gap. The US’ frequent shifts could create policy inconsistencies that weaken the collective front. Even when allies’ regulations strive to mirror US moves, implementation often lags. Worse, the unpredictability of U.S. policy shifts raises compliance risks for firms like Tokyo Electron and ASML, increasing the commercial burden of enforcement. Because these companies often operate at a chokepoint in the chip supply chain, every ripple from Washington’s decisions will be amplified at each node. Over time, such volatility may push allies to tweak their strategies: U.S. policymakers may tolerate the economic fallout of abrupt restrictions, but such smaller economies as the Netherlands and Japan face greater exposure. If credibility gaps persist, the result may not just be weakened coordination but diverging sanction approaches within the allied camp.

Coordinated sanction would be undermined when alignment with US policy becomes more costly and uncertain. For allies, it suggests a future of case-by-case coordination rather than a predictable framework of fixed rules. For China, meanwhile, carve-outs are possible when its leverage is strong, whether through control over rare earth exports, approval of U.S. corporate deals, or access to its vast technology market.

Therefore, the impact could be limited for Beijing. The re-entry of H20 will ease short-term capacity constraints for large-model training, but China’s advanced-node manufacturing push remains primarily state-driven. “Self-reliance and controllability” remains the core goal. With the world’s second-largest tech market and a deepening pool of AI talent, China’s trajectory in both hardware and algorithms is shaped less by external supply than by internal mobilisation. Past episodes have already shown how domestic mobilisation offsets external pressure: sanctions have accelerated substitution in chip design at HiSilicon, lithography and packaging at SMIC, and adoption of open-source architectures such as RISC-V. H20 may provide temporary relief, but it does not alter the long-term trajectory of catch-up, where China seeks to close gaps through state-backed investment and domestic innovation. The key question is less whether short-term carve-outs ease immediate bottlenecks, but more whether a mobilised system can sustain catch-up as AI transitions from an emerging field to a mature general-purpose technology for frontier developments.

Concerns are also rising in Europe. Even though the AI Diffusion Rule was withdrawn, its proposed three-tiered chip export regime sent a wake-up call. EU companies like SAP and Bosch, which rely heavily on NVIDIA technologies, now see their vulnerabilities stemming from US policy swings. If Washington continues tightening controls while chip downgrades fail to halt China’s AI progress, European interests are likely to diversify through non-US supply routes, turning to South Korean, Taiwanese, or domestic European providers. Rather than a performance choice, these alternatives are primarily as resilience tool that provide a hedge against persistent US export tightening. Over time, Europe is accelerating a decentralisation of global tech ecosystems and reposition itself in the US-China–EU technology triad, less as a dependent partner and more as an autonomous broker.