Published

Promoting a “GVCs for LDCs” Approach: The Case of Digital Certification for Organic Products

By: Lucian Cernat

Subjects: Digital Economy

As in any other day of the year, billions of people around the world woke up on the 1st of October and started their daily routine with a cup of coffee. Except that on that day – the International Coffee Day – the coffee may have had an extra special flavour. This was even more likely for those people enjoying a cup of organic coffee. And this is most certainly the case if you tried a cup of top, award-winning coffee produced by Ethiopian or Rwandan producers, like the ones winning the Illy International Coffee Awards.

Incidentally, if you enjoyed a cup of organic coffee in Europe, the product has been imported using a digital organic certificate. You may think that this is not a big deal. In an age dominated by disruptive technologies such as omniscient chatGPT-like artificial intelligence and omnipresent sensors and connected devices, one would expect the trade formalities required by the over 30 million containers criss-crossing the world to be conducted more often than not in a paperless environment. Paradoxically, the opposite is true. The International Chamber of Commerce estimated that 99% of such formalities are still conducted on paper. A single shipment can require up to 36 documents and 240 copies for only one cross-border transaction.

Despite this paradox, there has been great interest in new digital tools that could facilitate global trade along complex supply chains. IBM and Maersk proved that we can safely rely on digital documentations to export flowers from Mombasa to Rotterdam. Tens of other digital trade solutions, blockchain-based or not, have been tested both by the private sector and public authorities.

While the pace of digitalisation in the realm of trade procedures has accelerated greatly, this has also led to a concern about a digital divide being created between developed and developing countries, particularly the least developed country. Against this background, the current blog provides a prime example of a digital tool for trade facilitation (TRACES) that has successfully integrated the least developed countries and their small producers into global supply chains.

The TRACES digital tool has been introduced by the European Commission to facilitate the compliance of several imported products with the legal requirements in the Single Market. It covers many types of certificates, such as sanitary and phytosanitary certificates required for the importation of animals, animal products, food and feed of non-animal origin and plants into the European Union. The electronic certification capability of TRACES has revolutionized the traditional sanitary and phytosanitary certification practices by enabling both EU and non-EU authorities to digitally stamp official documents and certificates, thus, making the use of paper certification obsolete.

In 2017 TRACES started to be used for issuing Certificates of Inspection for Organic products (COIs). EU organic production standards require the certification for all products and the actors involved in their production, handling, processing and marketing. Only products certified can be labelled with the EU organic symbol. These requirements also apply to imported products. To ensure compliance, the EU has put in place TRACES – a modern, digital certification system that ensures traceability, origin verification and quality controls.

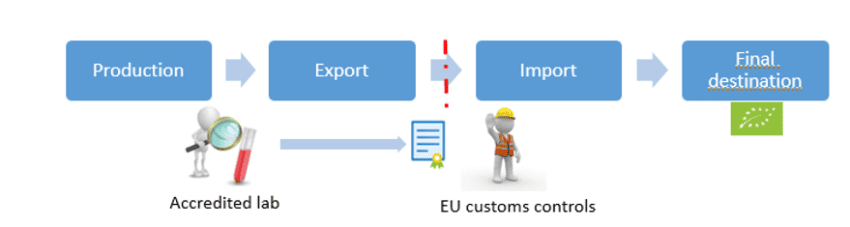

The organic products database in TRACES contains around 1 million firm-level EU import transactions of organic products between 2017 and 2022. The dataset includes several parameters and identifiers (producer, exporter, country of origin, country of exportation, HS code (8 digit), description of the organic product, its organic certification status, quantity). Figure 1 below illustrates the basic mechanism the main actors involved and their responsibilities in ensuring trust in the certification process and full traceability along the production chain.

Figure 1: The TRACES platform for organic digital certification

Source: Author’s elaboration

The digital organic certificate includes relevant information for the traceability of products. This information is uploaded by different actors, verified and validated with electronic signatures. The system has been widely adopted by producers and exporters around the world. Since its introduction in 2017, the organics module, has been adopted by tens of thousands of economic operators around the world, exporting organic products to the European Union. Among those there are also many organic farmers and exporters located in LDCs.

The rather unique, detailed firm-level trade data for EU imports of organic products allows an in-depth assessment of the adoption by LDC exporters of digital certificates for organic products. Moreover, since the EU organic regulation requires strict monitoring of various production methods used for organic products, as well as their traceability from “farm to fork”, the TRACES database also allows to assess the participation of LDCs as intermediary suppliers along complex, global supply chains for organic products.

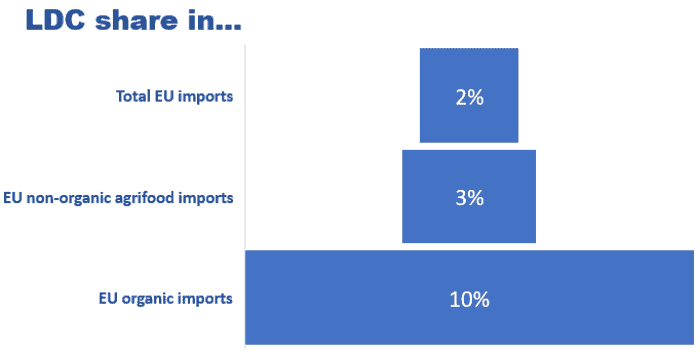

The detailed data allows us to draw a few interesting conclusions. Perhaps surprisingly, the data indicates that LDC exporters of organic products are very competitive in the EU market. The share of LDC in total EU organic imports is three times higher than their share in EU total food imports, and five times higher than their share in total EU imports. This is very good news for trade-led development, for several reasons. First, being competitive in the organic products market means LDC exporters specialise in products that have higher price premium than non-organic products. There is also a strong correlation between organic farming and fair-trade certification, indicating that there is a mechanism to ensure that this price premium trickles down to farmers and producers.

Figure 2: LDCs exporters are competitive in organic products

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on the TRACES database and EU trade statistics

A second interesting finding, reinforcing the fact that LDC organic farming is competitive, is that there has been a steady growth in the share of LDC exporters in total EU organic imports, from less than 5% in 2018 (the first year after the introduction of digital organic certificates) to 10% in 2022. As direct exporters to the EU, LDCs can compete successfully in organic products, head-to-head with major trading nations. For instance, Togo is among the top 10 exporting nations of organic products to the EU, surpassing other top suppliers like Colombia, Brazil, Mexico, or South Africa. Burkina Faso exports more organic products to Europe than Costa Rica, Thailand or the Philippines. Uganda exports more organics than Chile, Morocco, or New Zealand. Madagascar exports more organics (in value terms) than Japan or Australia. And yes, Ethiopia is a top exporter of organic products in the EU market, ahead of the United States, Indonesia, or Vietnam.

The other piece of good news, although perhaps not so surprising, is that the vast majority of LDC exporters of organic products are small exporters. Among all LDC exports of organic products to the EU using the TRACES platform, 82% are small exporters. This clearly indicates that the worries about digital trade tools acting as new barriers against small exporters are not warranted. LDCs exporters, large and small, are capable of complying with the trade formalities and with the digital organic certification procedures in the TRACES. The growing share after the introduction of digital certificates indicates that they can benefit from such digital trade facilitation tools.

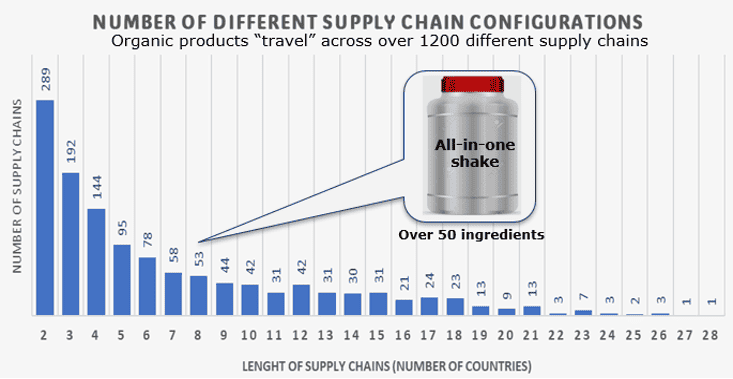

Finally, and perhaps most importantly from a trade perspective, is that LDC exporters sell their organic products both directly to the EU market, but also along global production chains, before reaching the EU consumers. Due to the traceability requirements for organic products and the need to ensure their organic labelling requirements along the supply chain, the online certificates in TRACES indicate the various intermediate countries that are involved in the supply chain, prior to EU importation. Most products do arrive in the EU directly from their single country of origin but others are part of various supply chains. When looking at all possible country combinations that are engaged in organic supply chains, the TRACES data indicates that EU imports of organic products may “travel” along over 1200 distinct supply chains.

Figure 3: The complex supply chains behind trade in organic products

Most supply chains are short, involving only two countries (e.g., one country providing one ingredient to the final producer/exporter in another country) before the organic product is imported in the EU. However, as shown in Figure 3, your all-in-one, high nutritional value shake powder can have more than 50 ingredients. Such ingredients can come from multiple countries. The most “globalised” organic product in the TRACES database involved 28 different countries.

Surprisingly perhaps, when compared to the very low participation of LDCs in global supply chains in general, LDCs are highly competitive in specific intermediate organic products that are key ingredients for many processed products along GVCs. For instance, some organic intermediate ingredients are to a very large extent sourced in LDCs (e.g., vanilla, Arabic gum). LDCs also have a high participation in the supply of other intermediate organic ingredients (e.g., cocoa, soya beans, sesame, vegetable fats, mango) for a wide range of more processed organic food products.

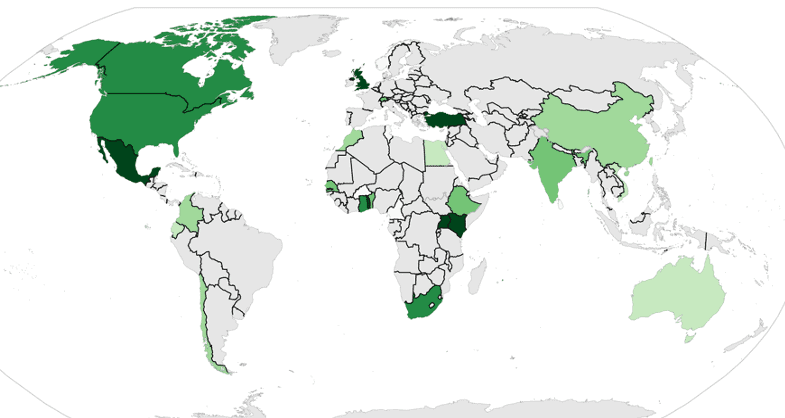

Figure 4: The importance of GVCs for LDCs in organic products

Countries that use LDC organic ingredients in their exports of processed organic food

Legend: Darker colours represent higher LDC value-added content in those countries’ organic food exports to the EU. EU countries that re-export LDC value-added as part of their organic food is not included, due to lack of data in the TRACES database.

LDC organic products are exported indirectly along supply chains to the EU via 24 other trading partners. Digital certification along supply chains facilitate the integration of LDCs in global supply chains. Major processors and “re-exporters” of LDCs organic ingredients are spread on several continents (Mexico, Turkey, the UK, United States, Canada, South Africa, Kenya etc.). This indicates that digital trade tools, like TRACES, facilitate the integration of LDCS in global supply chains, and act as a #GVCs4LDCs initiative. The organic product market is a lucrative market but, when it comes to the potential “GVCs for LDCs” trade facilitation of digital tools, the full potential is much bigger. If small organic farmers can go digital, any LDC exporter can. This lends support to the “re-globalisation” idea championed by Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, WTO Director General. She is confident that more can be done to support LDCs participating in GVCs, especially since such “GVCs for LDCs” initiatives can attract new investments in LDCs and expand their productive capacities.

Let’s go back to coffee, to prove that this potential is concrete and not just an inspirational quote. By now coffee (together with tea) has become the biggest agrifood export from LDCs to the European Union. Yet, despite this strong trade performance, LDCs have been struggling to fully benefit from the global value chains (GVCs) that underpin world trade today. I could write another #tradeXpresso Lungo coffee but let me put it simply: coffee beans from Ethiopia don’t always go straight into your cup. Coffee is further processed and becomes an ingredient not only in George Clooney’s most favourite capsule but also in many other drinks and food products. Coffee beans are a great source of antioxidants, protein and fibres that are used in novel, healthy foods. Apart from coffee, these products have one other thing in common: they pay tariffs, including on the value of those coffee beans from LDCs. That’s not ideal for trade and development. The good news is that there might be a few things we could do about it. Plus, this new idea has a cool name: #GVCs4LDCs!

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not represent an official position of the European Commission.