Published

Grumbling in the Fields: EU Agriculture and Trade

By: Oscar Guinea Bruno Capuzzi

Subjects: Agriculture EU Trade Agreements EU-Mercosur Project European Union Latin America North-America Regions Sectors

*The views expressed herein are individual to the author and do not represent any official position

European farmers have taken their tractors to the streets. Their list of complaints can be summarised in three points: tight margins; increasing environmental regulations; and competition from international markets.

In relation to the last complaint, European farmers claim that they face unfair import competition. They argue that European rules that regulate the production of food are stricter than international practices, putting them in disadvantage. Worried about international competition and a potential surge in foreign imports, they oppose the EU’s Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with Australia, New Zealand, Mercosur, Chile and Mexico.

Let’s put these claims into context. First of all, most of the food consumed within the EU originates from domestic production. According to the European Commission (EU production – balance sheets, area, production and yield by EU country), the EU’s agricultural output is more than enough to cover all of EU’s consumption across most agricultural products.

The food that the EU produces and does not consume finds its way into global markets. In fact, the EU is among the largest exporters of agri-food products in the world! Between 2018 and 2022, the EU enjoyed a positive trade balance in agri-food products that averaged €60 billion per year. Behind these export numbers were 25,000 European companies, 94 percent being small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

For cereals, oilseeds, protein crops, sugar, and meat, imports from outside the EU accounted for around a quarter of EU consumption (EU production – balance sheets, area, production and yield by EU country). Many of these imports are crucial for the competitiveness of Europe’s agriculture sector. Typically, European farmers buy agricultural inputs from international markets and focus on selling processed food products. Foreign agricultural imports supplement Europe’s production capacity, diversify its sources of supply, and enable European farmers to specialise in higher-value goods. This benefits everyone: it allows European farmers to increase their profits and fosters greater resilience. Research suggests that open agricultural markets tend to be more resilient and less volatile compared to closed ones (See here and here).

Certain agricultural products imported by the EU benefit from low or zero import tariffs. One prime example is soya, which currently enters the EU market duty-free and is an essential feedstock for European bovine, swine and poultry breeding. However, in general, agricultural imports face higher tariffs compared to other goods. The EU’s weighted average Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff for agricultural products stands at 8.4 percent, compared to just 2.9 percent for all imported goods (WTO, EU Tariff Profile). Sensitive agricultural sectors, where EU domestic production competes directly with foreign producers, are subject to significantly higher tariffs. For instance, imported fresh beef incurs in a 12.8 percent tariff and an additional €300 per 100kg (EU Customs Tariff, HS line 02013000). Additionally, quotas protect these sensitive products by limiting the total quantity of EU imports.

Second, some of the European farmers’ concerns about international trade can be tested. Let’s take two of the most sensitive European agricultural products: beef and poultry, and the competition European producers face from the Mercosur countries. Some claimed that the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement will lead to a surge in EU imports of beef and poultry from Mercosur.

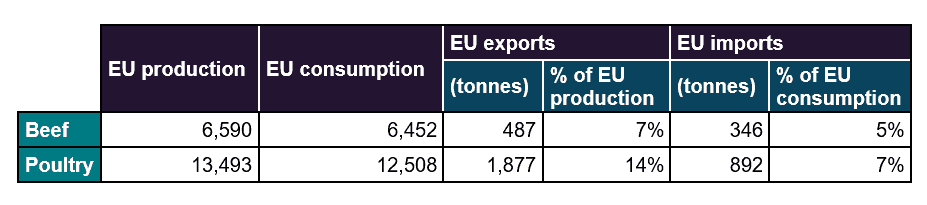

The EU produced 6,590 thousand tonnes of beef and 13,493 thousand tonnes of poultry. This output surpassed EU consumption, reaching 102 percent of EU’s demand for beef and 108 percent for poultry. A portion of this production finds its way abroad: 7 percent of European beef and 14 percent of poultry is exported. In relation to domestic consumption, the EU imports a small share of its beef (5 percent) and poultry (7 percent) consumption from outside the bloc. The table below summarises these statistics.

Table 1: Production, consumption, export and imports of beef and poultry in the EU (2023, thousand tonnes carcass weight equivalent)

Source: European Commission. EU agricultural outlook 2023-35. Figures 7 December 2023 (https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/data-and-analysis/markets/outlook/medium-term_en)

The EU-Mercosur Association Agreement treats beef products differently from the general trade liberalisation process. It would implement two tariff rate quotas (TRQs): one for fresh beef (7.5 percent duty for the first 54 thousand tonnes) and another for frozen cuts (7.5 percent duty for the first 44 thousand tonnes). Similarly, for poultry, the agreement will eliminate tariffs on 90 thousand tonnes to each quota of fresh and frozen poultry. Once these quantities are reached, imports will be subject to the current tariffs.

In 2023, the EU imported from Mercosur 85 thousand tonnes of fresh beef; 56 thousand tonnes of frozen beef cuts; 214 thousand tonnes of fresh poultry; and close to 10 thousand tonnes of the frozen poultry (Eurostat. TRQs BF1, BF2, PY1, PY2).

Comparing the current import levels with the quotas negotiated in the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement shows that the negotiated quotas are below the current level of EU’s consumption of Mercosur beef and poultry. Therefore, since the entire quotas’ volumes are already exceeded by an existent demand that fits EU consumption, it is unlikely that the reduction of duties would lead to an increase in imports. Moreover, these quotas only represent 2 and 1 percent of the EU’s consumption of beef and poultry, which significantly reduce any effect that the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement may have on Europe’s beef and poultry’s market. To put this into perspective, the beef and poultry TRQs negotiated in the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement are equivalent to less than 2 burgers and 2 poultry fillets per EU citizen per year.

The EU-Canada Trade Agreement (CETA) offers the same conclusion from the opposite angle: the existence of a TRQ per se does not create trade if there is not demand. Since 2017, Canadian farmers have enjoyed duty-free beef quotas when exporting to the EU. However, Canadian beef have never surpassed 3 percent of that quota. In 2023, only 1 thousand tonnes of Canadian beef out of the 50 thousand tonnes that can be imported duty-free were sold from Canada (European Commission, quota orders 09.4280 and 09.4281).

Finally, there are concerns that Mercosur exports may drive down EU beef and poultry prices. However, evidence suggests otherwise. According to the EU agricultural outlook (Baseline tables, Figures from 7 December 2023), the average market price for EU-produced beef in 2023 was €4,875 per tonne, while Mercosur beef imported into the EU was valued at €8,930 per tonne. Similarly, the average price of EU-produced poultry was €2,675 per tonne, compared to €2,712 per tonne for Mercosur poultry imported into the EU. Contrary to being low-cost products outcompeting local producers, Mercosur beef and poultry were more expensive than European domestic production (Import prices calculated from Eurostat data for TRQs BF1, BF2, PY1, PY2).

In conclusion, while European farmers face genuine challenges, concerns about international trade appear overstated. Rising input costs have outpaced final price increases in some agri-food products, squeezing farmer’s income. EU regulation restricts certain agricultural practices, rubbing salt in the wound of the already high administrative burden faced by many farmers. However, when it comes to international trade, complains about an overwhelming influx of foreign imports are largely exaggerated. The EU boasts high levels of self-sufficiency; European farmers are global leaders in agri-food exports; and EU tariffs and quotas shield some domestic producers from foreign competition.

5 responses to “Grumbling in the Fields: EU Agriculture and Trade”