Published

Globalisation After COVID-19

By: Erik van der Marel Oscar Guinea

Subjects: Digital Economy DTE Healthcare Services WTO and Globalisation

It is certain that the world will overcome the COVID-19 crisis, as much as it is certain that in the aftermath the world will look different with regards to global trade. International trade patterns will change, not only because governments are currently using commerce as a policy lever to fight this pandemic – either by imposing trade restrictions or by lowering tariffs – but also because of more structural factors, such as the push for digitalization.

Examples around us are telling. For instance, the US-based company Zoom that provides video-conference services is starting to gain ground in many European countries. The app is now used for all sorts of meetings outside business meetings such as family chats and online classes. Its share valuation has indeed rocketed in recent time[1].

But also other businesses using digital applications and technologies – from e-commerce to cloud computing and online banking – are all vivid examples of firms that have seen an increase of activity since the outbreak of COVID-19. Interestingly, digital content providers such as YouTube, Amazon and Netflix have adjusted their streaming quality to help the telecommunication network in handling the surge in demand for films, series and other online content.

Generally speaking, these are anecdotal stories, but they are likely to predict a larger trend of the direction in which globalisation is shifting. In our view, the current pandemic will accelerate the process of digitalization that was already underway in the global economy.

Past research corroborates this argument. During the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, it became clear that services trade was a lot more resilient than the trade in goods. Considering that many services are very digital-intense because of their widespread usage of software and other digital technologies, it is likely that we will see this again.

True, global trade performance in services was sluggish before the outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis. The latest WTO numbers showed that services trade was flattening or even in decline in the third quarter of 2019. In that regard, the contraction of services trade seems to follow the path of goods.

However, when taking a closer look, this decline was not uniform. Trade in commercial services such as financial, telecom, business or information services, still experienced positive growth. Many online activities fall into this category. On the other hand, transport services, manufacturing services, and maintenance and repair services showed the sharpest decrease in the third quarter of 2019. In short, it’s goods-related services trade, not digital services trade that is rather in decline.

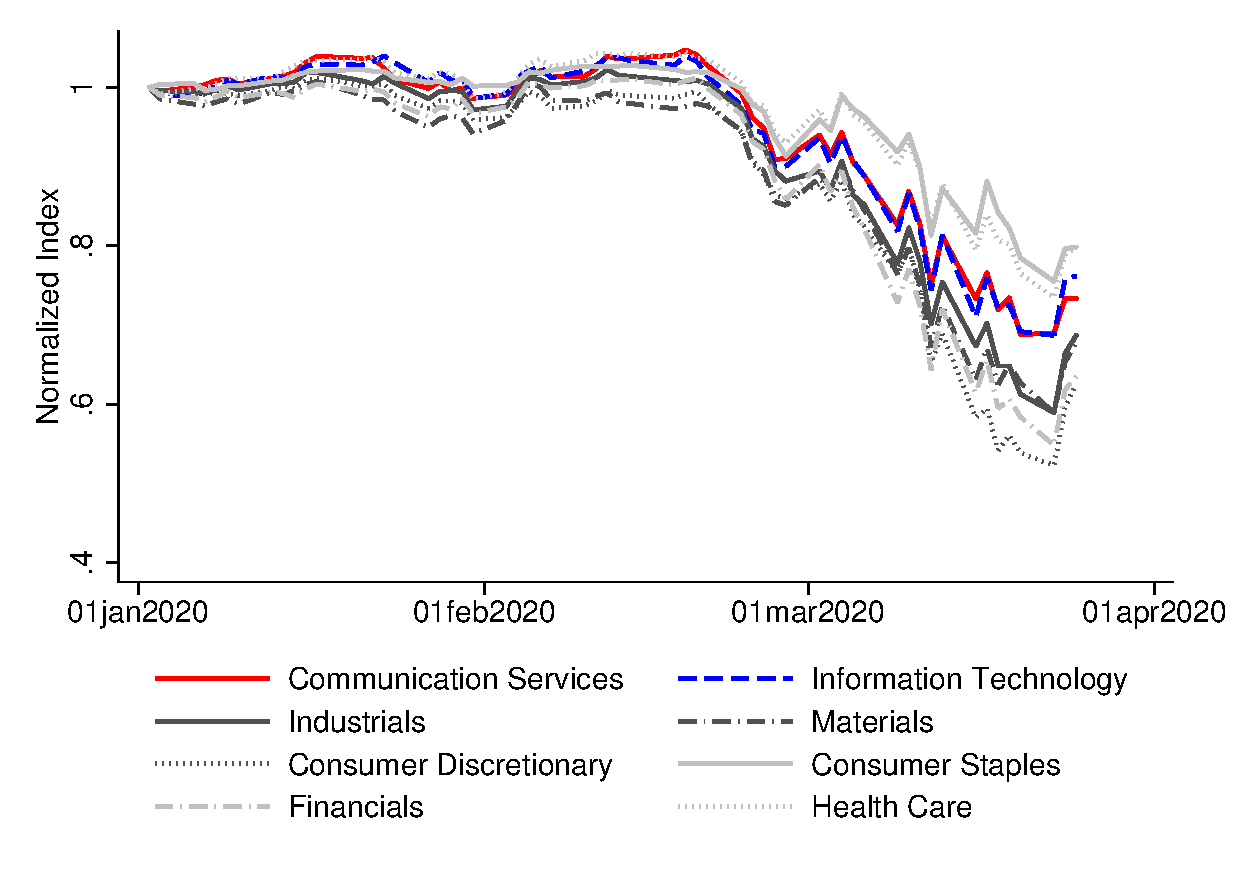

Of course, the future of globalisation cannot be predicted, and past experiences do not provide any guarantee. Yet, data patterns closer to date may reveal further insights, namely data on the recent changes in the US stock market prices. This data can be considered as a short-term indicator of where globalisation is likely to be heading. The figure below shows some revealing patterns.

Figure 1: Stock Market Prices, S&P 500

Note: Our dataset contains S&P 500 daily share prices between 2nd January 2020 and 25th March 2020.

One striking result is that the non-digital sector suffered more than the digital part of the economy. While companies belonging to consumer discretionary – which is comprised of non-essential goods and services such as durable goods, leisure and cars – materials, and industry have been hit the hardest, digital companies have seen a much lower decrease of their stock market prices.

Indeed, the relative decline of companies in communication services and the information technology sector is lower. They suffered a great deal too, but much less so than the analogue part of the US economy. Stock market prices are no structural indicators such as trade and productivity, but if anything, these patterns are surely indicative of investors views on the profitability of various industries.

What does this mean on a wider scale? And what does it mean for companies not belonging to the digital economy? It’s likely that firms in non-digital sectors will continue to digitalize their operations, but perhaps now even at a faster pace. This is because they are incentivized to absorb more big data, AI and other digital technologies, which will impact the way we produce and trade. A telling example is education. As a response to the confinement, many universities and schools that previously saw digitalization with ambivalence are now teaching online.

This is a welcome development given that a higher absorption of digital technologies is a significant determinant for long-term productivity, and necessary for a speedy recovery after COVID-19 – with a different type of globalisation this time. A type of globalisation that is more intangible and better supported by digital technologies.

[1] Zoom share’s value increased from $1.1 on the 2nd of January 2020 to $10.4 on the 25 March 2020. Source: https://www.marketwatch.com/investing/stock/zoom

3 responses to “Globalisation After COVID-19”