Published

Germany’s Industry Isn’t in Decline, It’s Changing

Subjects: European Union Services

Germany’s industry is in turmoil. Last year’s headlines about mass layoffs by German industrial giants like Volkswagen, Thyssenkrupp, BASF, and Continental were striking—but hardly surprising.

Experts offer numerous reasons for the root causes of Germany’s economic problems, ranging from increased energy prices and high labour costs to the country’s political culture and excessive bureaucracy. Yet the underlying forces of the Germany economy point to another unavoidable conclusion: downsizing the industrial labour force is, in the end, inevitable.

Economics, often misunderstood, operates under its own immutable laws. One of them asserts that as countries grow richer, they initially add more industrial jobs to the economy. But, after reaching a tipping point, they begin shedding factory jobs. Instead, economies create more intangible and services work, ranging from diligent engineers to smart consultants.

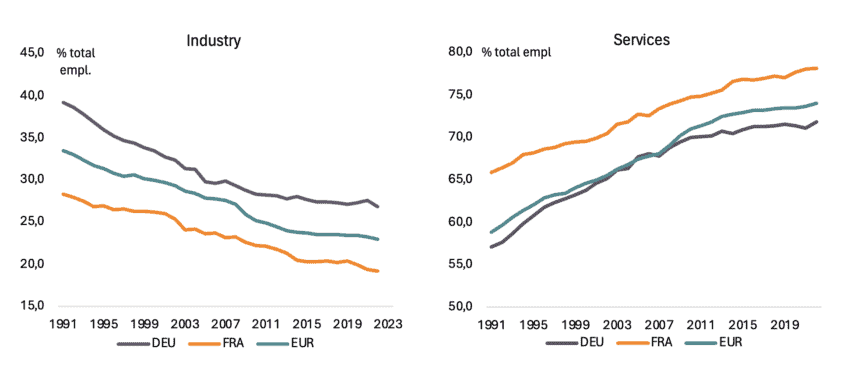

Germany is no exception. Its glory days of manufacturing jobs growth are long behind it, having peaked already in the 1980s. Since then, the share of industrial work has steadily declined, dropping from 40% in 1990 to just 27% today (left panel). Over that same period, a rapidly growing share of jobs in Germany has shifted to services.

Figure: As industrial jobs decline, services jobs rise, but in Germany at a slower pace Source: Author’s calculations using World Bank WDI

Source: Author’s calculations using World Bank WDI

For a long time, however, many thought of Germany being an exception from that law. After all, it was able to continue its industry dependency and consistently maintained a higher manufacturing share than France, another European industrial heavyweight. Germany also managed to slow its decline: while manufacturing jobs in other Eurozone countries continued to plummet, Germany’s post-Global Financial Crisis drop was only half as steep as the Eurozone as a whole. In fact, Germany still holds a strong comparative advantage in manufacturing.

However, Germany is just like every other country. Like all countries around the world, service jobs will inevitably start to outpace factory jobs in Germany. Even China, the world’s factory floor, won’t escape this tipping point. Since 2013, and despite the country’s manufacturing rebound, its industrial share in the economy has actually begun to decline (although its employment not yet)—a fate mirrored across the entire globe.

Does this mean deindustrialisation is at real risk in Germany? Not quite. Like the trend across the entire Eurozone, Germany’s manufacturing contribution has remained steady since the 1990s. The industry’s share of GDP has consistently hovered around 30% and has even increased in recent years. Therefore, as Germany’s share of manufacturing jobs began to decline, its share of manufacturing value added held steady.

How is that possible? Surely, technology is the main factor to look at. As automation takes hold, factory workers are the first to be ousted by robots and machines, creating more value added. But this hardly spells the end for industry—or the jobs it creates.

For instance, since the 1990s, Germany’s leading industries—motor vehicles, pharmaceuticals, and transport equipment—have expanded significantly. At the same time, they have integrated a larger share of modern services and other intangibles into their business models, driving a rise in service-related jobs.

Germany’s problem, however, is that it hasn’t done enough of it (right panel).

Take Tesla, for example, a powerhouse of modern services. In recent years, Tesla poured $4.4 billion into innovation, while Volkswagen, a much larger company, spent nearly $20 billion. Yet, Tesla still outshines its competitor: for every car sold, it pulls nearly 40% more R&D services than Volkswagen, pushing up demand for top-tier engineers, software designers, and mobile service technicians. Notably, Tesla’s market capitalisation has grown to exceed $1 trillion while Volkswagen stands at about $50 billion.

The Tesla example underscores what’s truly at stake: industries adopting new technologies are sparking a surge in demand for modern, highly skilled workers, often found in services industries. That’s not only true for electric vehicle technology – or for Germany. In Europe, highly skilled labour jobs drive roughly a third of AI adoption among firms. Firms where over half the workforce holds a university degree account for more than half of Europe’s AI uptake—without any sign of widespread job losses.

Many of these skilled labour jobs are in modern services, where advanced technology meets specialised activities in areas like digital, professional, scientific, and technical engineering, driving the expansion of the intangible economy.

But in Germany, the uptake of these human capital skills in manufacturing has been stagnant since the 1990s. While France saw growth of 27%, Italy 25%, the Eurozone 30%, and Poland an astounding 129%, Germany managed a paltry 0.5%. WIPO, the world’s agency that promotes global innovation, shows that Germany’s intangible investments have substantially lagged expectations since 2011.

The result is that Germany’s value of skilled exports has also fallen behind. Among Europe’s major markets, Germany stands out as one of the countries, along with France, where growth in high-skilled value-added exports has been the lowest. Measured in skilled occupations, this growth has been even negative, trailing other EU countries where it has been positive. It’s not that Germany hasn’t experienced an export boom over the last four decades—it has—but the boom was fuelled by relatively middle-tech industries.

Germany is already gearing up for a modern intangible economy. The latest employment figures, cited by the Economist, reveal the strongest recent job growth in sectors that absorb and generate a lot of high-skilled labour value, mainly in services, such as IT and technical and research services. Another indicator shows that Germany’s start-ups are predominantly concentrated in digital services.

However, these figures don’t signal the end of Germany’s industrial power. The same employment data also show that the next wave of high-growth sectors is based on aerospace, defence, medical tech, and pharmaceuticals—all manufacturing industries driven by intangibles, innovation, and service intensity. Even emerging sectors that Germany may aim to specialise in, such as green tech, are highly intangible and driven by modern services, including renewable energy and sustainable resource management.

In short, Germany is late in shifting to a modern economy because it has focused too long on its traditional strengths in heavy industries, like cars and machinery, without much modernisation. However, as the world economy is undergoing changes, it doesn’t mean Germany’s industry is in decline or approaching a near-zero industrial economy. Instead, its industry is evolving, albeit delayed.