Published

Sorry, Mr Draghi, but EU Exports are not a Drain on Competitiveness

By: Oscar Guinea Fredrik Erixon

Subjects: European Union

In a recent article in the Financial Times, Mario Draghi argues that the EU’s level of trade openness is unusually high and, in effect, a problem. In his view, Europe’s openness results from persistent internal barriers and weak domestic demand, making a large trade sector more of a vulnerability than a strength. We believe this perspective on the EU economy misses the mark – and ignores one central point: EU trade with the rest of the world has grown because global economic expansion has been so much faster than Europe’s economic expansion. In a world where 90 percent of new global economic growth happens outside of the EU, it is imperative for our own prosperity that European firms can access this growth. Therefore, the EU’s trade with the rest of the world aligns with its ambition to boost competitiveness.

Draghi’s desire to reduce EU trade openness takes the discussion in the wrong direction. Yes, of course, we all want faster growth and higher demand in the EU – but neither can sustainably be delivered artificially or by fiat. There isn’t a switch for higher growth that our politicians have forgotten to activate. While there are cyclical aspects of the EU’s trade profile, its structural performance is a deep-seated reflection of how its economy is structured and what happens in world demand. It’s true that the EU’s trade as a share of GDP exceeds that of the US and China, but it is not unusually high. The EU may have a single market, but it is not one national economy: it remains a large group of smaller and mid-sized economies that all come with a longer history of specialisation through trade. In 2022, the EU ranked 100th out of 130 countries for trade openness. If the EU were one country, it would fall in the 77th percentile, meaning its trade openness would exceed only 23 percent of all other countries in the world. Contrary to Draghi’s suggestion, the true outliers of trade openness are the US and China. The US ranks 128th, just ahead of Ethiopia and Sudan, while China stands at 116th.

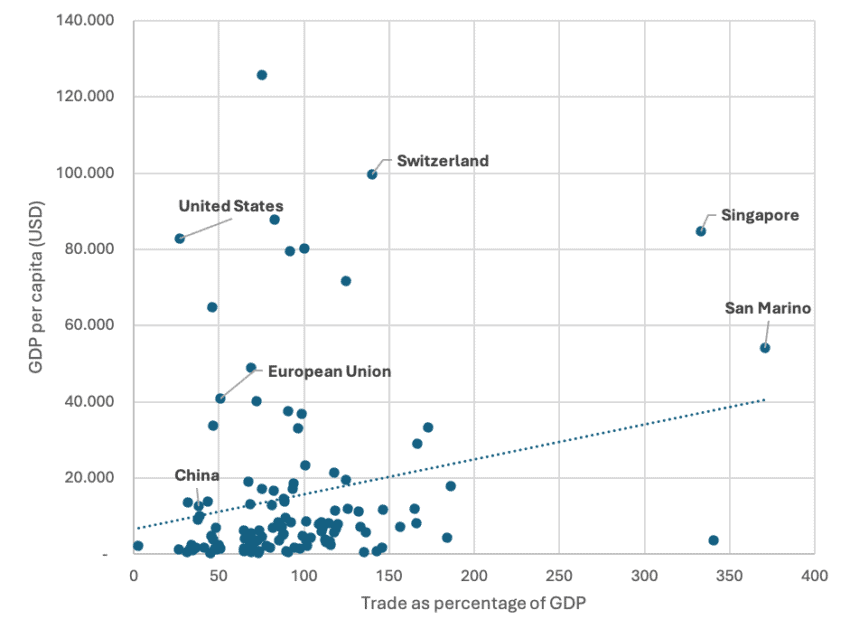

Moreover, evidence clearly shows that trade remains closely linked to economic success. Figure 1 presents trade openness, measured as the share of trade in goods and services relative to GDP (x-axis), alongside GDP per capita in USD (y-axis). The positive correlation highlights how greater trade openness goes hand-in-hand with higher economic prosperity. There is, of course, obvious explanations to this correlation: trade allows countries to build scale and specialise its economic assets (e.g., human capital) and to access competitive goods, services, technologies and ideas from abroad. EU exports directly support 38 million European jobs, with small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) making up 87 per cent of all EU exporters. Moreover, there is a strong intimacy between trade and cross-border investment, allowing better allocation of capital and competition between firms and organisations. Countries that have tried to reduce trade by policy restrictions have not just found that it is expensive but that it reduces competition and sets in motion a development that make economic progress more costly.

Figure 1: Trade openness and GDP per capita Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the World Bank.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the World Bank.

In Draghi’s way of thinking, the success of European companies in exporting goods and services comes from weak domestic demand, pushing firms to seek growth abroad. It is of course correct that businesses look for new customers where there is new growth and purchasing power, but with an industry structure like Europe’s it would be very implausible that faster growth at home could compensate for growth abroad. The same logic, of course, applies to each EU member state: if the German economy had grown, say, like the Chinese economy, German automobile manufacturers would not have sold so many additional cars in Germany that it could have avoided selling cars in China. Faster growth and higher demand in Europe would have an impact on trade performance, but the most plausible effect would be higher levels of imports, leading to a reduced trade surplus.

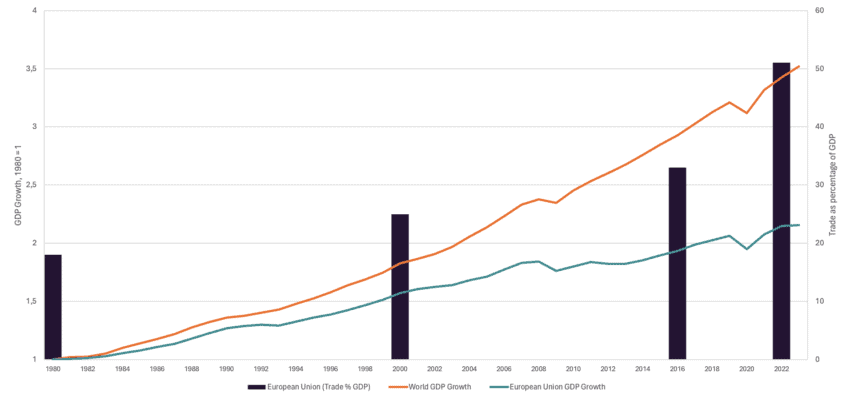

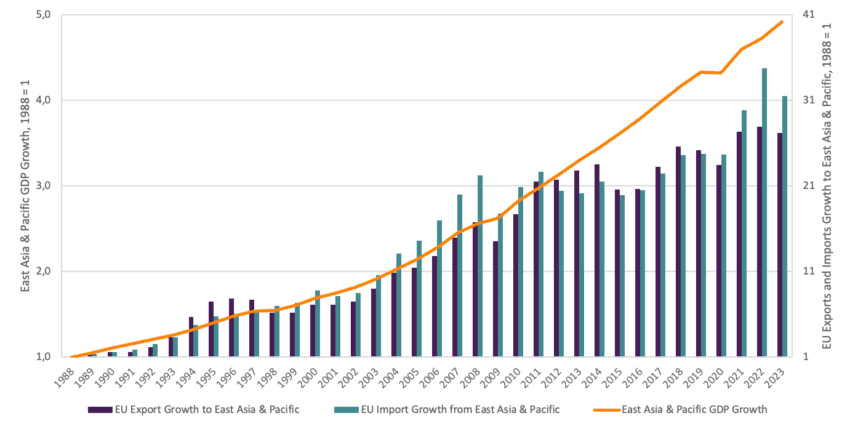

The key point is that Europe’s trade performance – measured by the size of its trade sector relative to GDP – reflects faster growth of global demand compared to European demand. Figure 2 presents World and EU GDP growth during the last 43 years alongside Europe’s trade openness in 1980, 2000, 2016, and 2022. While the EU’s GDP doubled between 1980 and 2023, global GDP expanded more than threefold. It was only natural for European companies to seek opportunities and start sourcing their inputs from abroad. Figure 3 highlights GDP growth in the East Asia and Pacific region alongside the growth of EU exports and imports with the region from 1988 to 2023. The figure shows that EU trade closely tracks economic growth in the region. The real concern would have been if they had not kept pace.

Figure 2: GDP growth (1980-2023) and EU trade openness (1980, 2000, 2016, 2022) Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the World Bank and Eurostat.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the World Bank and Eurostat.

Figure 3: East Asia and Pacific GDP growth and EU Exports and Imports Growth to East Asia and Pacific (1988-2023) Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the World Bank and UN COMTRADE.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the World Bank and UN COMTRADE.

Draghi is right to highlight the unfinished EU single market. Removing internal barriers to trade in goods and services should remain a core priority for the EU. The same IMF research cited by Draghi in his Financial Times article (see Figure 1.2.2, page 18) shows that trade costs with the rest of the world remain higher than within the EU. While it’s true that global trade barriers for services have fallen faster than those within the EU, this reflects both the EU’s slow progress in deepening its single market for services and technological change – especially how digitalisation have reduced real trade costs across all countries. Still, EU companies are likely to find doing business with other parts of the world more challenging than within the EU single market.

Finally, Draghi takes a radical departure from the traditional view of trade and competitiveness as positively correlated. He argues that the EU’s trade openness has become a vulnerability, exposing the bloc to external shocks and geopolitical disruptions. There is no doubt that trade has increasingly been overshadowed by nationalist policies and concerns over economic security. Given Europe’s deep economic integration with the world, decisions made elsewhere – particularly in China and the US – affect the bottom line of many European companies.

But effective policies to address security and supply concerns are rarely about reducing trade generally. First, these issues need to be put in context: of all trade in goods that the EU engages in, only a very tiny subset is associated with concerns. Among more than 9,000 product categories, only 282 primarily originate from a limited number of non-EU countries. Of these, just 45 product categories – representing 0.4 percent of total EU imports – pose significant concerns, including critical raw materials and certain pharmaceutical ingredients. In services there is hardly any category where the import dependency is so high that it leads to a trade vulnerability.

The real challenge for Europe’s economic security is not trade itself but trade concentration. As the EU experienced during COVID-19, trade diversification against third-countries and itself proved to be a source of resilience. For instance, during the pandemic, the EU relied heavily on non-EU imports to meet soaring demand for medical supplies. Extra-EU imports of face masks surged by 769 per cent, while intra-EU imports rose by just 45 per cent.

Draghi’s article follows the same logic as his analysis in the now famous Draghi report. There is much to value in his report: his take on trade is not one of them. It offers a top-down, simplistic macro view on international trade, where the actual trade performance is the result of managed levels of demand or a fundamental change of the EU’s economic structure, making it more like America. The reality is different and the future is not likely to make Europe less dependent on the world. Europe’s share of world GDP, demand, R&D, IPRs, human capital and more will continue to shrink because the rest of the world is growing faster. If we want faster growth in Europe, we will need to be better positioned to benefit from these global expansions.

Yes, there are emerging geopolitical shifts that are dangerous to Europe’s security. Our best way to address these problems is to establish so much military capacity that it deters aggressors. Vulnerable trade dependencies can be managed and radically reduced – but not by unsustainable and artificial measures that make the region to trade substantially less. Trade openness does not undermine EU competitiveness, it strengthens it.