Published

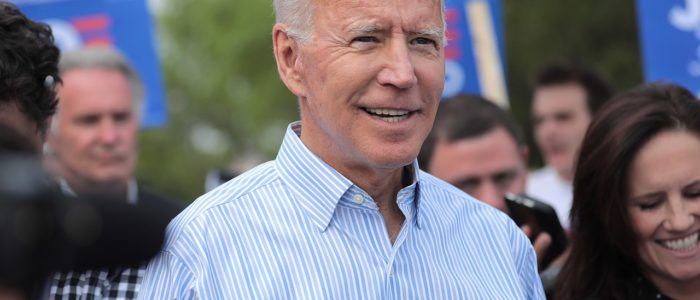

A Biden Win Won’t Fix the World Trade System

By: David Henig

Subjects: North-America WTO and Globalisation

A US Presidential election always exerts quite a hold on the political world’s attention, but not often with personal stakes as high as they seem to be in 2020. Quite simply the entire rules-based international system seems at high risk from a re-elected President Trump. He has already given notice of intent to withdraw from the World Health Organization, and US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer demanded fundamental reforms of the World Trade Organization, with a clear threat to further disrupt operations or leave if they are not fixed. For the WTO that would come on top of previous disruptive US activities including preventing the functioning of the appellate body and signing deals with Japan and China that appeared to breach fundamental rules.

It would be fair to say that a large majority of international policy makers who support sustaining the current system hope Joe Biden wins the election for the Democrats. Not universally, for Trump has his supporters in London, Brasilia and even Beijing, though in many cases their professed support for the system is somewhat shaky. But largely, in the hope that a Biden victory means the problems of the last four years can be forgotten and peace restored to international relations and world trade.

Certainly there should be less overt conflict with trade partners under a Biden Presidency. At times in the last four years it has been hard to keep up with exactly which countries Trump is threatening with what measures, though this is oddly interspersed with what appears an almost psychological need for deals which has also seen agreements with China, Japan, South Korea, Mexico and Canada. Then there are the general investigations putting tariffs on steel and aluminium, and often threatening them on the automotive sector. There certainly appears to be no such things as allies in Trump’s trade world.

Yet the wide relief that might be felt at the election of a President Biden could be short lived. For behind the undoubtedly friendlier exterior would appear to lie similar instincts as to the way the US should conduct international trade policy. Recently published, “The Biden Plan to Rebuild U.S. Supply Chains and Ensure the U.S. Does Not Face Future Shortages of Critical Equipment” criticises President Trump for failing to being manufacturing jobs back to the US with a clear commitment to “use federal purchasing power to bolster domestic manufacturing capacity.” The traditional US trade policy on procurement then, and it seems likely that this will be accompanied by the usual promise to open markets for US farmers. The same document also sees harsh rhetoric against China, reflecting a bipartisan US view on the subject, and even the friendly talk of working with partners suggests that this should come through selling more US products to them.

Campaign talk of course, but there really doesn’t seem to a lot of thinking in the US about ways in which the problems that existed in international trade in 2016 can be fixed, or more specifically, what the US could do differently. To give a clear example, the growing concerns about the role of China in the world trading system were widely forecast, but the US failed to find agreement with the EU about shared rules in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, or with its own populace over signing up to the Trans Pacific Partnership. It remains hard to see how there can be meaningful reform of the WTO while differences between the US and EU remain on so many fundamental trade topics. But then resolving those would require both sides to take on key domestic interests such as their own farmers, since it is easy to imagine both US and EU farmers objecting to a deal such as the US ceasing to challenge EU food rules in return for full tariff free access.

This also speaks to a wider problem, which is the declining support for free trade. Opinion polls might suggest otherwise, but the version of free trade that the public support is the one with increasing exports and no painful trade-offs, not the real version in which the trade-offs are rather more apparent than the increased exports. It is protectionism that has been winning votes since 2016, in the US, UK, and EU, perhaps dressed up in trade rhetoric. Where are the global leaders wanting to take on their domestic interests faced with this public?

Which leads us to a fundamental problem in trade as in other fields, which is about the future of consensus based international organisations in an age of national populism. It seems difficult right now to imagine new agreements reducing governments’ rights to operate independently, and perhaps the best we can do is to retreat to fundamental values such as non-discrimination in the WTO, and leave those who want to go further to do so. On which basis the WTO will not be reformed any time soon, but some countries may choose to go further. The problem being that this is an inherently unstable polity.

Indeed, a pessimistic reading of President Biden’s election would be that while improving relations with traditional partners he will fail to deliver any fundamental change, while support in the Republicans for leaving global institutions like the WTO grows. This certainly seems as likely as the possibility of the party emphasising free trade as a policy.

Genuine globalists, those who actively want to see more imports, and are happy to see their own protectionist groups attacked, are right now in a very small minority in many countries including the US. While that’s the case, the election of a different President is most likely at best a sticking plaster over the problems. It is time the global policy community understood this, and started acting accordingly.