Services Trade Needs to be Taken as Seriously as Goods Trade

Published By: Anna Guildea David Henig

Subjects: New Globalisation Services WTO and Globalisation

Summary

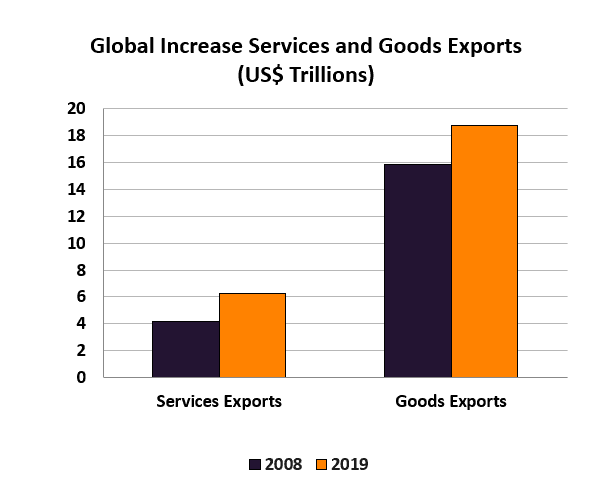

Services constitute at least a quarter of total trade. Between 2009 and 2019 global services trade increased by nearly 50%, compared to 18% for goods trade. Yet it is rarely taken as seriously as goods in global trade policy discourse. This is a problem when making the case for trade.

Introduction

There seem to be three major reasons why services trade is not taken sufficiently seriously.

- Definition: Politicians and specialists don’t fully understand what services trade involves and are then unable to elaborate the benefits of growing the sector – they may not even think of it as ‘real trade’;

- Measurement: Difficulties in counting services leads to oddities like the two largest services exporters claiming a surplus with each other, or iPhones being considered a product when their services components are of much greater value;

- Mutuality: Countries have found it difficult to demonstrate beneficial trade relations with other countries in services given that barriers are primarily regulatory in nature.

It is time to change the services narrative, to show that this is real and growing trade, and likely to increase in importance in the future. We need also to broaden the debate from generic consultancy or financial services to specifics like films or engineers. Developed countries particularly reliant on services trade should take that lead, tackling the problems and emphasising services as just as important as goods.

Defining services trade

There is no comprehensive definition of a service, except insofar as that which is not goods trade, to mean that no tangible product is transferred in ownership. Obvious internationally traded services include distribution, financial products and higher education. Less obvious are the status of mobile phone apps, which could be goods or services, goods sold as services such as car leasing, and the intellectual property contained within goods such as cars or computers.

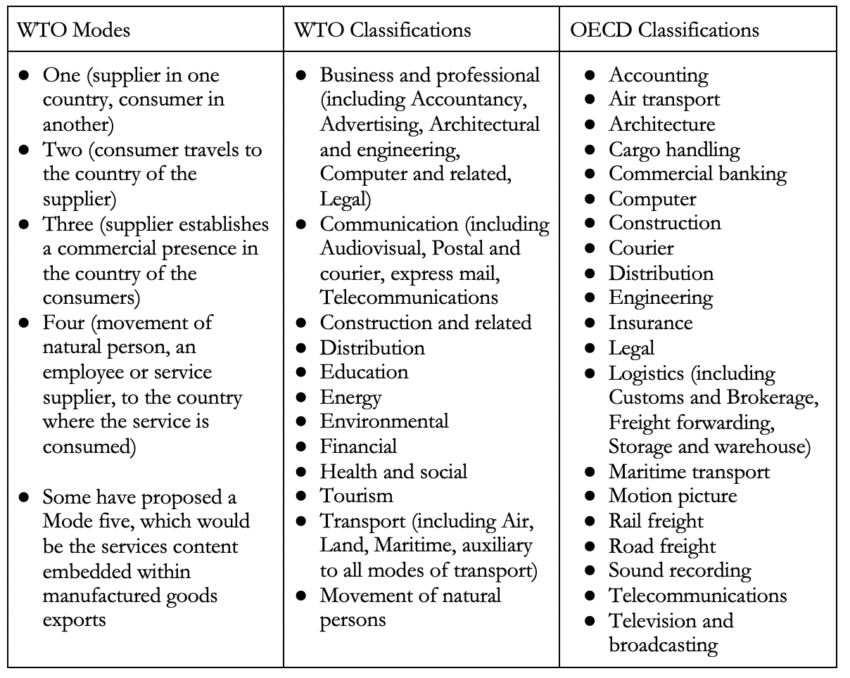

A key problem is the lack of an agreed international definition of services. The table shows different ways of considering services trade:

- Four defined modes used in WTO negotiations;

- Different sub-sector classifications used respectively by the WTO and OECD.

WTO modes of supply are particularly unhelpful to services being taken seriously. Commitments made this way were an attempt to create a measure similar to tariffs in building international agreements. However they are both unhelpful in understanding services trade, and no longer of much use in thinking about market access, where for example a consultancy service could be provided simultaneously in all modes. Similarly the right to theoretically sell services is of little use if there are multiple regulations preventing this.

WTO modes of supply are particularly unhelpful to services being taken seriously. Commitments made this way were an attempt to create a measure similar to tariffs in building international agreements. However they are both unhelpful in understanding services trade, and no longer of much use in thinking about market access, where for example a consultancy service could be provided simultaneously in all modes. Similarly the right to theoretically sell services is of little use if there are multiple regulations preventing this.

It is probably time to move on from modes of supply. For wider comprehension it would be best to combine OECD and WTO sub-sector classifications of services. This would particularly help show the diversity of services trade contribution to an economy, crucial for showing the benefits of global trade.

Measuring services trade (and why it may be greater than goods trade)

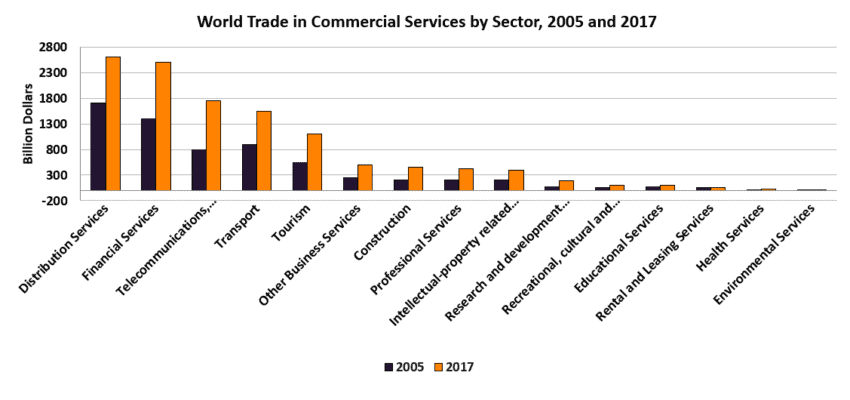

At an aggregate level, according to WTO data, over 50% of trade in services happens in distribution, finance, and computing / telecoms. Disaggregation of these categories would be helpful to demonstrating the importance of different elements that are understandable to individuals.

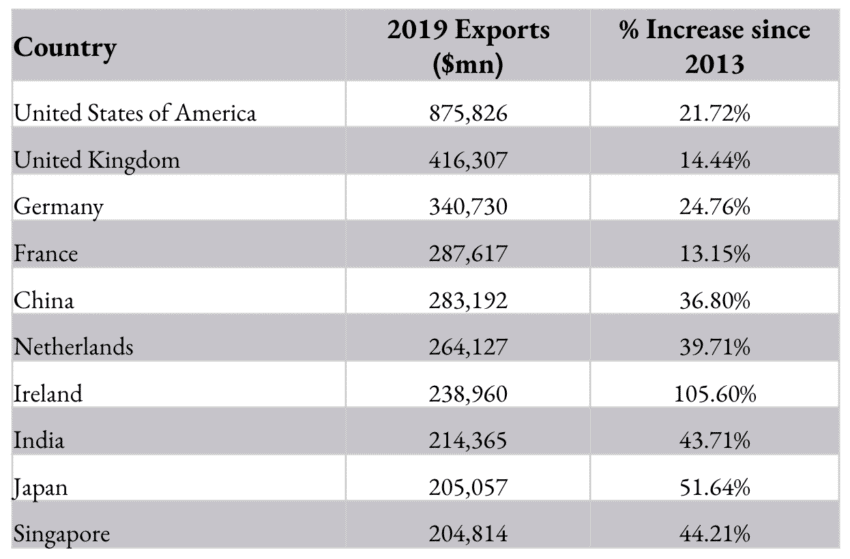

A bigger issue is that services data figures are beset by measurement problems, as unlike goods there is no clear point at which they leave one territory for another. This can be seen in trade relations between the world’s two largest services exporters. According to UK figures the country had a £35 billion services trade surplus with the US in 2019. On US figures the UK had a $16 billion deficit. The same problem affects UK-EU trade data, except that while US figures are lower than those of the UK, those of the EU are higher.

A bigger issue is that services data figures are beset by measurement problems, as unlike goods there is no clear point at which they leave one territory for another. This can be seen in trade relations between the world’s two largest services exporters. According to UK figures the country had a £35 billion services trade surplus with the US in 2019. On US figures the UK had a $16 billion deficit. The same problem affects UK-EU trade data, except that while US figures are lower than those of the UK, those of the EU are higher.

Some discrepancies may reflect an exaggeration of services trade, for example in accounting transactions for tax purposes claimed as intellectual property transfers. However there are also reasons to believe that services trade is under-counted.

One potential source of under-counting is ‘Servitization’, where products are sold as a service. Examples of this include the management and maintenance of a fleet of customer vehicles, and the likes of Microsoft, Netflix and Spotify delivering ongoing services rather than a physical product. Subscription model are increasingly common in different industries.

Another source of under-counting may be the services inputs into a final good, for example through research and development or the increasingly sophisticated computer systems that form part of so many physical products from cars to cookers. In the EU the trade of such services is estimated to be over €300bn, roughly a third of total goods exports.

Using a different analytical approach based on balance of payment data the WTO World Trade Report of 2019 suggested trade in commercial services was worth US$ 13.3 trillion in 2017, more than double the official number. Meanwhile, a McKinsey report estimated that counting unmeasured channels of services meant global services trade was higher than that for goods. More work is urgently needed on the real value of services trade.

Deepening the global services market

Another problem facing services trade is the difficulty of demonstrating mutually beneficial relationships. Governments and experts struggle to explain the uneven growth of services trade between countries, and what different actions or agreements may have contributed. This is not least as recent services trade growth does not appear to have followed any particular agreements.

Perhaps in part because of Ireland, governments are generally not confident services trade delivers real jobs and prosperity. Their narrative remains dominated by goods.In the particular case of Ireland there does appear to be distortion due to notoriously low corporation tax. Many multinationals set up campuses enabling them to shift profits made from services trade to being recorded as generated in Ireland, enticed by the country’s notoriously low corporation tax. This results in an artificially inflated rate of growth in Ireland’s services exports, and possibly a knock-on impact elsewhere in the world.

In that context it is interesting to contrast US and China exports. While Chinese goods exports have been increasing faster than those for the US, the opposite is the case for services, keeping total exports roughly equal since 2012. Yet US discourse is dominated by goods.

Taking services seriously would mean putting more effort into demonstrating how mutual agreements increasing services trade, and similarly how some do not. Commitments in Free Trade Agreements are often subject to numerous exceptions due to domestic regulations, and it is quite possible a better approach would be a permissive one with no obstacles to

Conclusion

Services trade is economically important. It is growing and likely to continue to do so. More people have direct experience of it than goods trade. Increasing numbers work in internationally traded services.

As yet importance of services trade is not however widely recognised. More government emphasis is needed. This includes accurate measurement, clearer definition, and innovative approaches in trade agreements. Doing so should also help challenge growing narratives about the problems of globalisation.