Trading Up: An EU Trade Policy for Better Market Access and Resilient Sourcing

Published By: Fredrik Erixon Oscar Guinea Philipp Lamprecht Oscar du Roy Elena Sisto Renata Zilli

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements Regions WTO and Globalisation

Summary

Europe’s competitiveness could be substantially improved by a trade policy that facilitates more trade and other forms of cross-border exchange. The evidence is clear: the EU trades less with the rest of the world than would be expected given the size of its economy. With 85 percent of global growth happening outside of the EU – and with an increasing share of all new technologies, innovations, patents, human capital, and R&D expenditure emerging in other parts of the world than Europe – the EU needs to find better ways to integrate with international markets. It is now becoming urgent for the EU to revive its international trade policy.

Europe’s increasing detachment from global markets lead to two major economic concerns: deteriorating market access and less capability to build economic resilience. Market access can be defined as an export challenge, as EU firms face increasing trade barriers that hinder their ability to sell products and services abroad. These barriers ultimately limit the EU’s ability to scale up production, specialise, and increase R&D spending. Economic resilience is an import challenge. To become more resilient, the EU must diversify its sources of supply, particularly for critical raw materials, and secure a stable and frictionless access to foreign high-end goods, services, and technologies.

The next five years present a critical opportunity for the EU to address the challenges limiting the contribution of international trade to EU’s competitiveness. This Policy Brief outlines seven trade policy recommendations that tackle the lack of market access and address the need for economic resilience. These policy recommendations are there for the EU to take: they are realistic and achievable. The EU has the power to make these seven policy recommendations a reality.

1. Modernise existing FTAs and conclude agreements with Mercosur, Australia and the ASEAN countries: there is untapped potential in the modernisation of current FTAs to improve market access and facilitate imports, particularly on raw materials, services, and clean technologies. The advantages of signing FTAs become clearer for countries with whom the EU does not have an FTA such as Mercosur, Australia and some of the ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Thailand or the Philippines.

2. Negotiate “Mini deals”: the EU should prioritise sectoral agreements in areas where global regulatory requirements diverge and in sectors where the EU demonstrates a comparative advantage. These targeted agreements, focused on major trading partners and high-volume sectors, can deliver benefits comparable to, or even exceeding, those of Free Trade Agreements.

3. Expand the adequacy framework for regulation: similar to the existing framework for personal data, the EU should develop a transparent and efficient process for countries to demonstrate alignment with EU regulations. This would facilitate predictable market access for foreign businesses, mitigating unnecessary costs and delays associated with importing into the EU market.

4. Join the CPTPP: the EU should apply to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Joining the CPTPP will allow the EU to shape trade rules, counter Chinese influence and expand its market access in the region.

5. Deepen Trade and Technology Councils (TTCs) with the US and India: the EU-US TTC should be broadened and serve as a springboard for new common standards and policies in trade, technology and economic security. Moreover, the EU should elevate the EU-India TTC, recognising India’s growing importance as a tech hub and talent pool.

6. Deepen Neighbourhood Policies on raw materials: the EU has a vital strategic interest in securing a reliable and sustainable supply of critical raw materials. Leveraging the Eastern Partnership and the Union for the Mediterranean, the EU can establish mutually beneficial partnerships to enhanced access to diverse and secure sources of these minerals and metals and boost local processing, refining, and recycling capacities.

7. Initiate a Trade Resilience Coalition: building upon the Ottawa Group’s collaboration during the Covid-19 pandemic, the EU should spearhead the creation of a Trade Resilience Coalition. This group of like-minded countries would proactively agree on trade rules and protocols in preparation for common response to sudden stresses in trade and supply chains.

Preface: From Barriers and Red Tape to More Trade Opportunities and Resilient Sourcing within and outside the Single Market

Europe Unlocked is a coalition of business organisations from across Europe, representing companies large and small, united in their belief that competitiveness and open markets should be at the heart of the policy programme for the next Commission. For Europe Unlocked, international trade beyond Europe’s borders is a necessity for a more competitive and therefore more prosperous Europe.

Under the current European Commission, there has been a concerted push across a range of policy areas to achieve greater European sovereignty which has meant, amongst other things, erecting barriers to trade rather than reducing them. This will drag on Europe’s competitiveness if left unaddressed. Our geopolitical strength will come from our economic success and forging new and valuable trade relations is an essential part of that mix.

We need to acknowledge that the vast majority of projected global growth will come from outside Europe and we need to grasp that opportunity. Trade helps firms to diversify, grow and innovate, all characteristics that are a must have and not just a nice to have for a more competitive Europe. If we are to be resilient in an uncertain world then we need to diversify sourcing strategies to help mitigate supply chain risk by reducing dependence on any single source for raw materials or components.

There are a few points that we think are particularly important in this respect:

First, if we are to increase trade opportunities and resilient sourcing then the Commission has to prioritise market access when negotiating agreements with third countries, this applies in multilateral negotiations through the World Trade Organisation, in bilateral Free Trade Agreements and new forms of trade and investment deals.

Secondly, when we talk about market access, we mean increased opportunities for exports, imports and investments and for both goods and services.

Thirdly, in terms of regions, we need to urgently ratify already concluded agreements with Latin American countries. We need new ambitious agreements to be concluded with India and Indonesia and also look to the Indo-Pacific region. We can’t afford to be passive and if Europe is not prioritising those relationships then others will.

We hope that this report will serve as an important contribution to the debate on Europe’s competitiveness. It is critical that we get this right if we are to secure a more prosperous future for Europe.

1. Introduction

Over the past five years, EU trade policy has languished. Although a handful of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) have been concluded, the overarching trend as far as new market access is concerned has been one of hibernation. Nor has the rest of the world become a more welcoming place for exporters and importers, providing natural and open access to their markets. The US and China, Europe’s largest trading partners, are pursuing inward looking policies aimed at reducing their reliance on other countries.

EU policymakers have made some efforts to address problems. The growing influence of geopolitics and the harm of rising energy prices on the EU’s competitiveness compelled the Union to proactively advance its international agenda. This commitment is evident in the establishment of the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC) and the EU’s agreements on critical raw materials (CRMs) with several countries. While these initiatives represent progress, they seem to function as shortcuts and workarounds to compensate for the EU’s otherwise stagnant trade agenda.

A paradigm shift is imperative. Europe is in urgent need of devising a new strategy to revitalise European trade and align it with its objectives on competitiveness and economic resilience. International trade is one of Europe’s main policy levers to revert the trend of declining competitiveness and confront the challenge of increasing dependencies. Freer trade is essential as a source of expertise, technology, and value chains – without which European competitiveness would fall markedly – and to boost demand for European products so European businesses can scale up production and specialise. Moreover, pursuing trade diversification – rather than concentrating on increasing domestic production – is the most cost-effective, risk-mitigating[1], and swift policy option for enhancing resilience, securing access to raw materials and reducing the economic leverage other nations may wield over the EU economy.

Europe’s trade problem is now becoming urgent. Weakened by low demand growth, poor productivity developments, and increasing business costs, the EU economy needs to better access customers, products, and technologies abroad and connect with the stronger economic dynamism of international markets. Europe represents a shrinking portion of global demand, growth, and innovation, and – unfortunately – international trade policy is not contributing to the EU’s prosperity as much as it could. The decline of the EU’s weight in global markets, alongside a reduction in the share of Europe’s exports relative to its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) are two revealing statistics. This Policy Brief highlights two areas that help us understand this trend: (i) market access, and (ii) economic resilience.

Market access can be characterised as an export challenge. As Europe’s proportion of the global economy diminishes, it is imperative that EU firms gain improved access to global markets to sustain growth in their sales. Economic resilience is an import challenge. Europe’s resilience depends on its ability to diversify trade and access the latest technology. Import tariffs and regulatory barriers that increase trade costs between the EU and other parts of the world undermine EU’s competitiveness and, by extension its economic resilience.

There are many opportunities, and reasons for optimism. The EU could implement policies aimed at reducing trade barriers for its exporters and importers – just as it has done in prior decades. Such efforts would create an expanding market for European businesses to sell abroad and a solid footing for businesses to buy the highest quality inputs and diversify their sources of supply.

The primary objective of this Policy Brief is to demonstrate how the EU’s trade policy can support the Union’s competitiveness, thereby making a significant contribution to productivity and economic growth in Europe. The next chapter delineates the two issues hampering international trade’s contribution to EU’s competitiveness: market access and economic resilience. To revert this situation, the third chapter presents a set of policies for the EU to rejuvenate its trade policy. The last chapter presents the main conclusions of the study.

[1] Guinea, O., & Forsthuber, F. (2020). Globalization comes to the rescue: How dependency makes us more resilient. ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 06/2020.

2. Market Access, Resilience and Europe’s Competitiveness

2.1 The Relation Between Trade and Competitiveness

International trade plays a vital role in driving the EU’s competitiveness and economic growth. At its core, trade serves as a dynamic engine of growth, making a positive contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This contribution extends beyond the simple arithmetic of national accounting. For instance, companies engaged in exporting tend to exhibit higher levels of productivity and innovation[1]. Moreover, engaging with global markets is not just a matter of expanding sales but is crucial for acquiring the technological and innovative inputs necessary for the EU to thrive in the global economy[2].

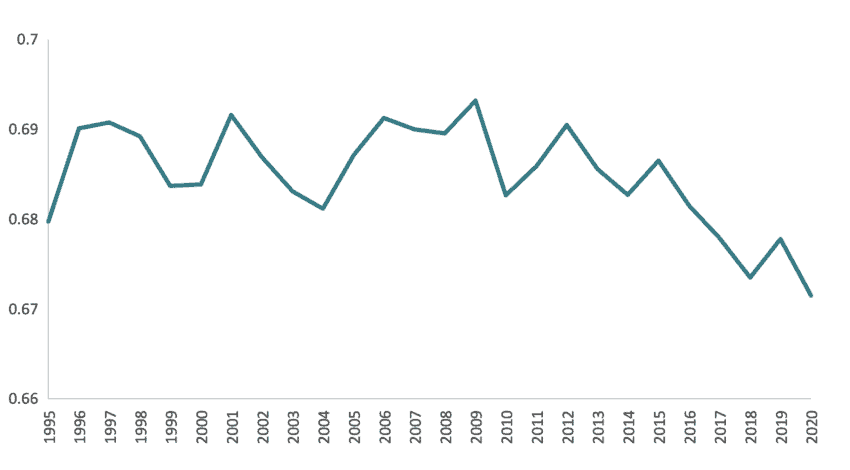

Yet, despite the positive impacts of international trade on competitiveness, the EU is not fully capitalising on these opportunities. Figure 1 presents the Extra-Regional Trade Intensity Index, a metric that measures the value of EU’s trade with the rest of the world relative to its overall economic size. With values consistently below one, this index reveals that the EU’s external trade is not performing at the level expected given its GDP. A trend that has been particularly pronounced since 2016[3].

Figure 1: Extra-Regional Trade Intensity Index, 1995-2020 Source: OECD TiVA, ECIPE calculation, ECIPE calculation.

Source: OECD TiVA, ECIPE calculation, ECIPE calculation.

Europe’s limited engagement[4] with the wider world is problematic for several reasons. Firstly, the vast majority of global economic growth is anticipated to originate from outside the EU. The IMF estimated that, between 2024 and 2028, EU’s GDP growth will range between 1.4 and 1.7 percent whereas emerging markets are projected to achieve economic growth rates of between 3.9 and 4.8 percent[5]. In its most recent trade strategy, the European Commission pointed to the fact that 85 percent of global growth happens outside of the EU – reinforcing the need to connect better with global markets.[6] Secondly, as emerging economies continue to modernise and developed economies advance the technological frontier, the EU will increasingly source new goods, services, and technologies from outside its borders.

2.2 Market Access

Market access, or the lack of it, significantly impacts the EU’s ability to export goods and services. It can be described as the degree to which the EU can enter foreign markets, subject to various tariffs, regulatory barriers, and other obstacles. Given the importance of exports as an engine of the EU’s economic growth, lack of market access directly hampers EU’s competitiveness.

Over the years, protectionist measures have escalated and evolved beyond traditional import tariffs. Between 2009 and 2023, European exporters faced a more than a 20-fold increase in non-tariff barriers, from roughly 500 to around 12,000 by 2023, with a notable increase in the last four years[7]. In 2023, for instance, French and German exporters of cars, iron, steel, and metal fabricated products such as tubes or wires, encountered the largest number of NTBs.

The rise of NTBs is also impacting EU’s services and in particular digital services. For example, the OECD found more than 100 data localisation measures, such as local storage requirements and flow prohibitions, that were enforced across 40 countries[8]. These measures, mostly driven by non-OECD countries, have a direct negative effect on EU firms, particularly in sectors such as e-payments, cloud computing, and air travel.

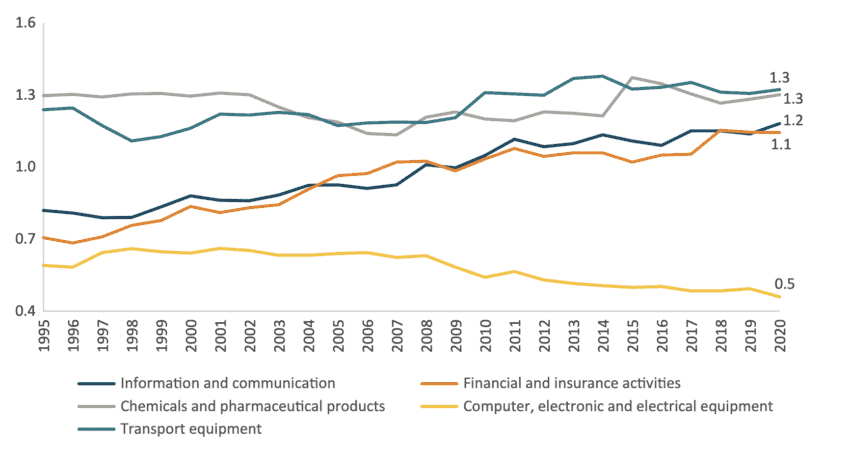

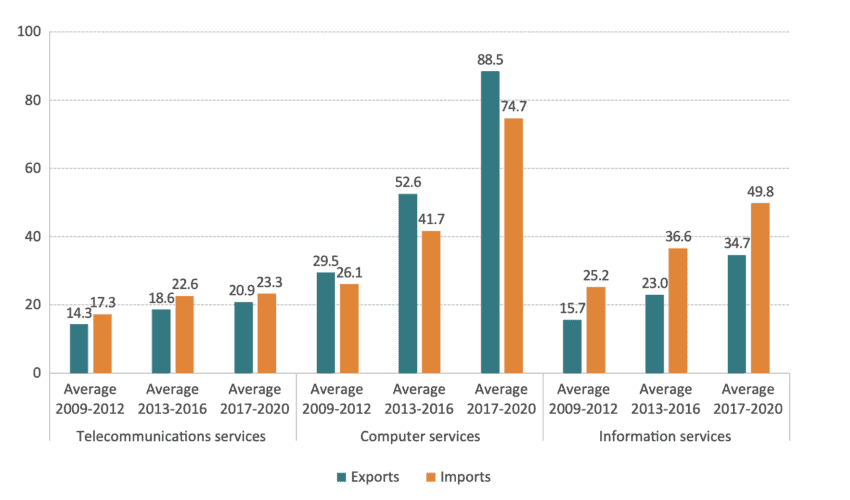

NTBs on services are critical because they hamper Europe’s new sources of economic growth and most promising companies. The EU’s international comparative advantage is undergoing a transformation, reflecting the broader shift towards a service-oriented economy[9]. This transformation is particularly evident within Europe’s ICT services sector. Between 2010 and 2020, exports of ICT services expanded at an average annual growth rate of 8.5 percent[10], surpassing the growth rates of EU exports in chemicals (2 percent), machinery (1.4 percent), and transport equipment (1.4 percent). Remarkably, the value of the EU’s ICT services exports in 2020 reached €158 billion, exceeding the value of exports in the EU pharmaceuticals (€129 billion), chemicals (€109 billion), and electrical equipment (€17 billion). [11] [12]

2.3 Economic Resilience

Economic resilience is the ability of an economy to absorb and recover from shocks, such as natural disasters, pandemics, or geopolitical conflicts, while maintaining its core functions. The significance of economic resilience for the EU’s competitiveness is twofold. Firstly, it reduces dependencies on third countries. Secondly, it highlights the importance of securing stable access to a wide spectrum of imports, from raw materials to cutting-edge technologies.

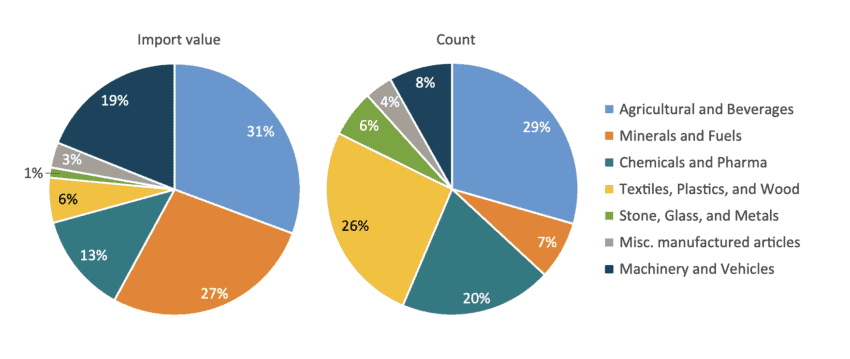

EU’s trade dependencies are linked to its ability to reduce its over-reliance on a single source of imports. From 9,000 analysed products imported by the EU, only 282 products, representing 2 percent (€58.5 billion) of EU total import values could be defined as dependent[13]. Moroever, not all the products classified as dependent are critically important to the EU economy[14].

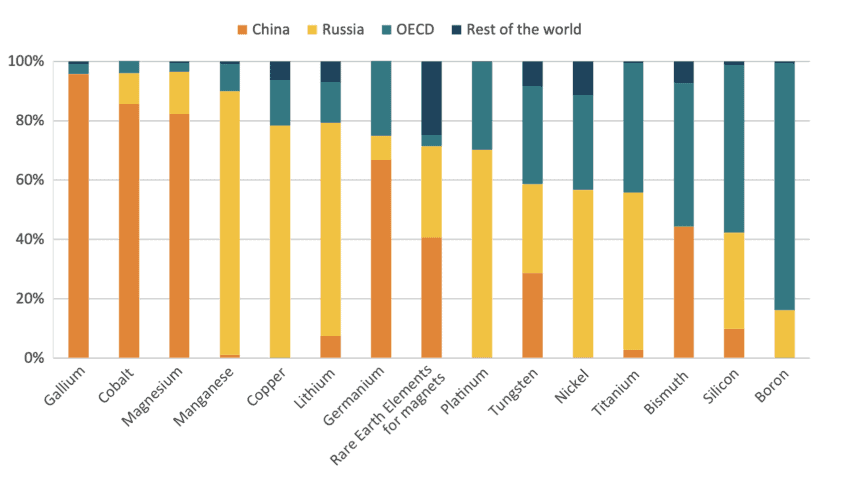

However, the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s weaponisation of CRMs have exposed real vulnerabilities associated with economic dependency on minerals and fuels. In 2022, the EU was highly dependent on China for gallium, cobalt, magnesium, and manganese, with imports from China constituting over half of the EU’s total imports for these materials[15]. CRMs are essential inputs for EU’s clean and digital technologies, defence and other critical industries such as robotics.

A secure, stable, and seamless access to high-end goods, services, and technology is also crucial for economic resilience. However, the primary barrier to sourcing high-end products originates from within countries themselves, rather than from their trade partners. In the past five years, the EU has established several trade[16] and digital[17] – including the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and the Artificial Intelligence Act – barriers that are likely to raise import costs and potentially drive a wedge between the EU and the global economy.

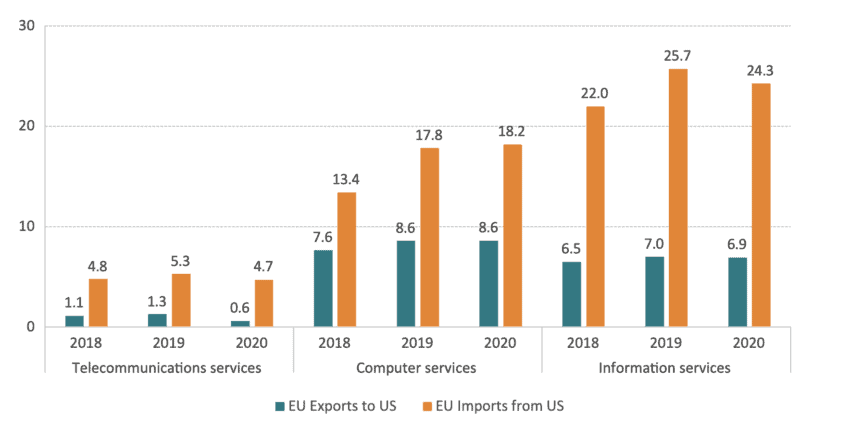

These trade barriers pose significant challenges to EU’s competitiveness. In 2020, US firms were the leading providers of ICT services to the EU market, accounting for 30 percent of total imports. EU imports of US ICT services[18] – close to €47 billion – contribute to Europe’s economic transformation reflected in the €158 billion of EU ICT services exported worldwide mentioned before. EU regulations that create barriers to the flow of goods, services and investment[19] between the EU and its main trading partners will have a negative effect on the EU’s competitiveness in these new sources of economic growth.

[1] Cassiman, B., Golovko, E., & Martínez‐Ros, E. (2010). Innovation, exports and productivity. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 28, 372-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINDORG.2010.03.005.

Salomon, R., & Shaver, J. (2005). Learning by Exporting: New Insights from Examining Firm Innovation. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 14, 431-460. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1530-9134.2005.00047.X.

Melitz, M. (2003). The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica, 71, 1695-1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

[2] Criscuolo, C., & Timmis, J. (2017). The relationship between global value chains and productivity. International Productivity Monitor, 32, 61-83.

Criscuolo, C., Gal, P. N., & Menon, C. (2017). Do micro start-ups fuel job creation? Cross-country evidence from the DynEmp Express database. Small Business Economics, 48, 393-412.

[3] It must be mentioned that the fall in the Extra-Regional Trade Intensity Index shown in Figure 1 is not just about decline; it is also about economic transformation and the shift towards services in trade, since many traded services tend to be traded regionally rather than globally.

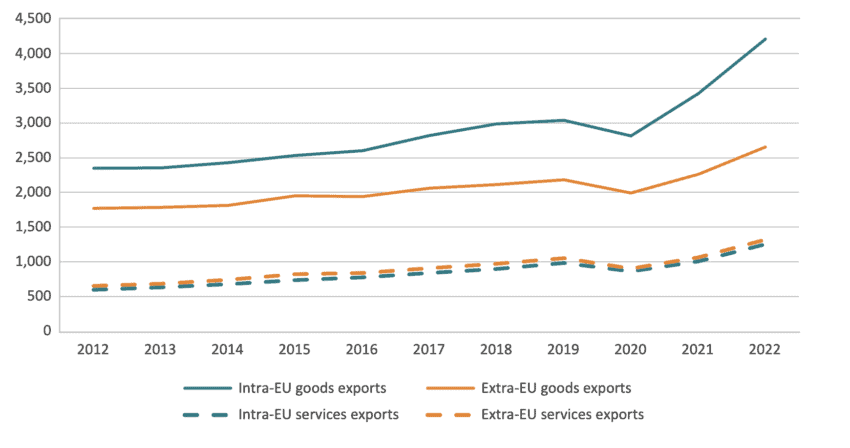

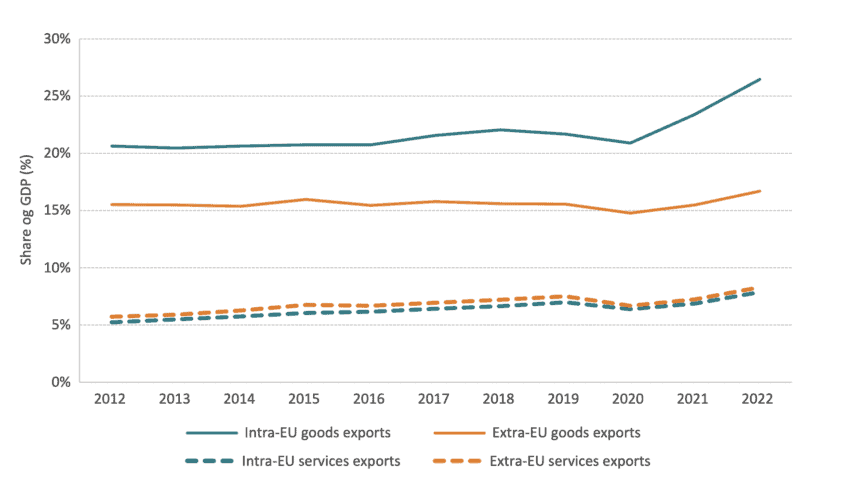

[4] For further evidence of Europe’s disengagement from the rest of the word see Figure 1 and 2 in the Annex. Figure 1 shows that intra-EU exports of goods are both larger and growing at a faster pace than extra-EU exports. Figure 2 shows the declining contribution of extra-EU exports to the EU’s GDP.

[5] IMF (2023), IMF World Economic Outlook 2023.

[6] European Commission (2021), Trade Policy Review – An Open, Sustainable and Assertive Trade Policy. COM (2021) 66 final.

[7] See Annex, Figure 3: Number of Non-Tariff Barriers affecting EU firms, 2009-2023.

[8] Del Giovane, C., J. Ferencz and J. López González (2023), “The Nature, Evolution and Potential Implications of Data Localisation Measures”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 278, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/179f718a-en

[9] See Annex, Figure 4: Shifts in the EU’s Revealed Comparative Advantage across various economic sectors.

[10] See Annex, Figure 5: The EU’s trade in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) services, 2010-2020, in billion EUR.

[11] Source. OECD TiVA. Sectors mentioned in the analysis and corresponding industry code: ICT services (J); Chemicals (C20); Other Transport Equipment (C29 & C30); Machinery and Equipment (C28); Electrical Equipment (C27); Electrical Equipment (C27)

[12] OECD TiVA original figures in US$. Transformed into euros using the average 2020 exchange rate from the European Central Bank. Source: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/euro_reference_exchange_rates/html/eurofxref-graph-usd.en.html

[13] See Annex, Figure 7: EU import dependency in goods, by product type (2022).

[14] See Annex, Figure 8: Highly dependent products categories, by import value and category count of products (CN codes).

[15] See Annex, Figure 9: Origin of EU imports of strategic raw materials in 2022 (in terms of volume).

[16] Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Lamprecht, P., Sharma, V., & Zilli Montero, R. (2022). The new wave of defensive trade policy measures in the European Union: Design, structure, and trade effects (ECIPE Occasional Paper 4/2022). European Centre for International Political Economy.

[17] Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Van der Marel, E., and Sisto, E. (2022) “After the DMA, the DSA and the New AI regulation: Mapping the Economic Consequences of and Responses to New Digital Regulations in Europe” ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 3/2022

[18] See Annex, Figure 6: EU-US trade in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) services, 2018-2020, in billion EUR.

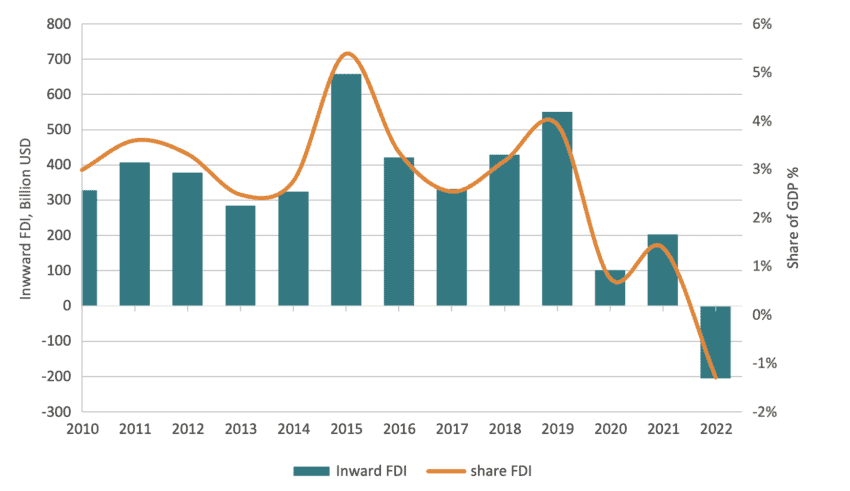

[19] See Annex, Figure 10: The share of inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) relative to the EU’s GDP.

3. EU Trade Policy: A Forward-Looking Agenda for 2025-2030

3.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter, we established that there are two key economic challenges where EU trade policy can place a crucial role in the next five years: boosting EU market access abroad and improving economic resilience, especially for critical technologies and materials needed for EU firms to be competitive. This chapter turns to policy approaches and outlines a set of policy recommendations that are aimed at achieving these objectives.

While the world of global trade policy rarely seems to invite optimism about global trade, the reality is that constructive and forward-looking trade accords are happening. There are more countries than perhaps meet the eye that are seeking deeper trade relations with other nations and regions, and some of these agreements are economically substantial and lead to important liberalisation. They are also helpful for the purpose of improving economic security by diversifying supply of critical goods and technologies. Indeed, the EU has been part in the negotiations of such agreements – for instance with Mercosur, New Zealand, and Australia. Unfortunately, the EU and its trading partners have not been able to finalise or approve many of these initiatives, and thus made the EU less powerful for its ambitions to improve both prosperity and security through trade[1].

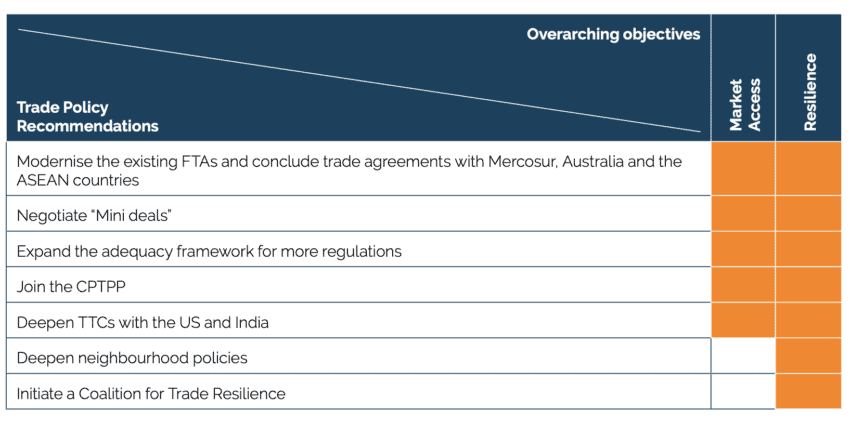

For the next five years, we propose 7 actions in EU trade policy that are feasible and that do not require a wholesale shift in the Union’s current defensive attitude to trade. Table 1 below outlines what these measures are, and how they connect with the objectives of market access and economic resilience. Most actions benefit both objectives, even if the emphasis may be stronger for one rather than the other objective.

Table 1: Key trade policy actions 2025-2030

3.2 The FTA Agenda: Modernise Existing FTAs and Conclude Agreements with Mercosur, Australia and the ASEAN Countries

The EU has a substantial body of Free Trade Agreements with other countries and regions in the world. There are currently 41 FTAs, Economic Partnerships Agreements (EPAs), or Association Agreements (AAs) in force between the EU and 72 countries, directly supporting 36 million jobs in the EU.[2] Obviously, there are also FTAs that could have been wrapped up and soon entered into force if there had been support for them – such as the negotiated agreement with Mercosur.

However, concluding and ratifying any FTA is a complex process requiring time and willingness from both negotiating parties. In other words, the EU is not solely responsible for the recent slowdown in new FTAs. Nevertheless, it is not a secret that some EU member states have impeded the ratification of FTAs due to domestic reasons, and EU negotiators have self-imposed limitations on liberalising sensitive sectors like agriculture. This severely hinders the EU’s ability to secure new FTAs with food exporting countries.

The existing FTAs are of varying quality: some are ambitious and important for Europe’s trade while others had less impact even at their start or outset. Most agreements, however, had inadequacies or were incomplete already at their stage of conception. And since they entered into force, the economy and trade restrictions have changed, and most agreements need to be modernised in order to maintain relevance. The average EU FTA dates from 2009 and six out of ten EU FTAs were signed before 2014.

There is a significant untapped potential in the modernisation of current FTAs: this potential includes both the desirability of improving European market access abroad and making it easier to import from other countries. In comparison with some of the EU’s more recent FTAs, older agreements cover fewer areas of the economy and trade barriers. For instance, the EU-Canada and EU-Japan FTAs included 10 and 13 legally enforceable policy areas outside the mandate of the WTO[3] respectively. In comparison, EU FTAs signed before 2017 only included, on average, 4[4].

Currently, the EU has started negotiations on modernising FTAs with 12 countries. This process has already yielded a new agreement with Chile and amendments to the Association Agreement with Moldova. Notably, there are significant opportunities to update the EU’s trade agreements with its neighbouring countries. For instance, the EU has bilateral trade agreements with countries around the Mediterranean that are important for the diversification of mineral imports. Many of these agreements lack sufficient rules and disciplines to offer predictability in trade. With new EU policies coming in – such as the Carbon-border Adjustment Mechanism – that will have an impact on trade in raw materials, it is even more important to agree better rules and disciplines in trade with raw-material rich FTA partners. The EU has started negotiations for the modernisation of its FTAs with Azerbaijan, Morocco, and Tunisia but these negotiations have stalled for some time.

Services are also an important area for FTA modernisation. Most EU FTAs had a positive impact on services trade, but these agreements were also incomplete and have become even more inadequate over time. New services trade restrictions have impacted both exports and imports, and trade in sectors of substantial EU comparative advantage has not increased as much as it could have grown. The EU itself has also been a source of these new frictions, and the growth of services trade restrictions in the EU is a good basis for revisiting FTAs to improve their importance for market access and resilience.

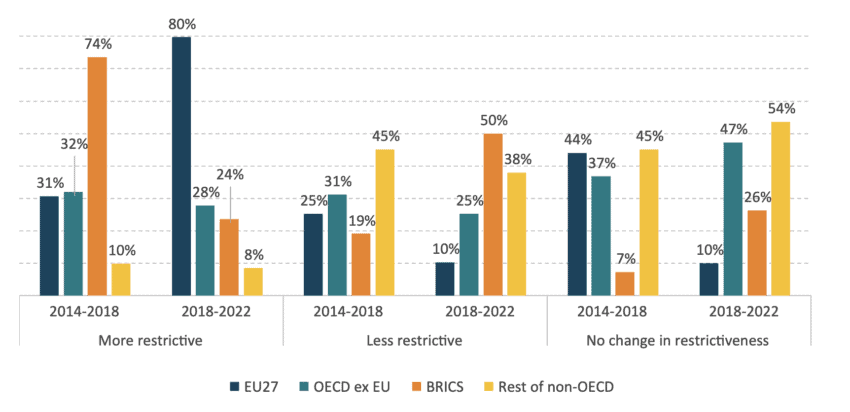

Figure 2 reinforces this point. The figures compare developments in services trade restrictions between different groups. For the general trade restrictiveness of services, OECD STRI data reveal notable changes in trade policies across regions and time frames. Within the EU22[5], there is a striking increase in services trade restrictiveness from 31 percent in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 80 percent in the period 2018-2022. This substantial surge in the “More restrictive” category signals a significant tightening of regulations affecting services trade among EU Member States. The sharp decline in the “Less restrictive” category, from 25 percent in the total number of country- and sector-specific observations in the period 2014-2018 to 10 percent between 2018-2022, indicates a reduction in measures that facilitate freer services trade. Another aspect is the prevalence of “No change in restrictiveness” at 44 percent and 10 percent for the two respective periods. Overall, this suggests a certain degree of complacency within the EU, with a reluctance to revise or enhance existing services regulations and trade policies, potentially hindering the adaptability of the services market to emerging economic challenges. Importantly, the figure shows that real developments on the ground have changed and thus impacted on many existing bilateral agreements.

Figure 2: Development of services trade restrictiveness, 2014-2018 and 2018-2022 Source: OECD STRI data, ECIPE calculation. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Source: OECD STRI data, ECIPE calculation. Percentages based on differences between the values at the beginning and at the end of the respective periods. Values > 0 equals “More restrictive”, values < 0 equals “Less restrictive”.

Obviously, the modernisation of EU Free Trade Agreements should include more sectors and areas than raw materials and services. Cleantech and industrial sectors are equally important, and will become even more as more economies deepen their efforts to reduce carbon emissions. Provisions to protect intellectual property rights are inadequate in many existing EU FTAs. The list can be made longer and varies from agreement to agreement. The general point, however, remains: there is an upside opportunity for the EU in a revitalised FTA agenda.

3.3 Negotiate “Mini Deals”

In the past year, so-called mini deals have emerged as a new concept for thinking about trade policy. While it has been common to conceptualise trade agreements as all-encompassing – covering most (if not all) sectors and including rules and disciplines – the reality is of course that no trade agreement ever have passed the standard. Multilateral agreements as well as Regional or Bilateral Free Trade Agreements have always been incomplete, and the best ones have acknowledged this reality and created new impulses to continue expanding the depth and width of the agreement in the future.

As observed in an important paper for conceptualising the mini deals, mini deals have really been part and parcel of EU trade policy for a long time and represent a much higher share of EU trade agreements than for instance FTAs.[6] Essentially, mini trade deals are targeted agreements between countries to reduce or remove non-tariff barriers (NTBs) and enable a reduction in bilateral trade costs. This broad category of legal trade instruments could and should be used in sectors where global regulatory requirements have diverged, leading to (often) unnecessary trade and administrative costs. In fact, due to their relatively smaller scope compared to deep and comprehensive trade agreements, a much larger number of such mini deals have been concluded in the EU but also the US[7]. The cumulative impact of this trade policy tool is therefore an important lever to facilitate trade.[8]

Negotiating mini deals in digital services and e-commerce could significantly enhance EU market access and bolster economic resilience. The European Commission has started to deploy such agreements by signing a digital partnership with Japan in 2022. Such mini deals could tackle specific obstacles impeding the free flow of data, foster mutual recognition of digital standards, and facilitate cross-border e-commerce. These agreements have significant potential. The OECD’s found that a 0.1-point increase in the average Digital Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (DSTRI) between countries can lead to a 15.4 percent surge in international trade costs[9]. This impact is most noticeable in digitally-deliverable services, yet it also affects sectors such as food, agriculture, and manufacturing.

Within mini trade deals, mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) are a particularly effective tool to reduce costs from different regulatory product requirements. This is also where there are many upside opportunities in the next five years for the EU: it can negotiate sectorally-targeted mini deals that build on the principle of mutual recognition. In fact, given that EU tariffs are generally low, focusing on various forms of costs that arise because of regulatory developments is going to be a chief way for the EU to reduce trade costs, boost market access, and deliver better opportunities for importers to diversify their sources of supply.

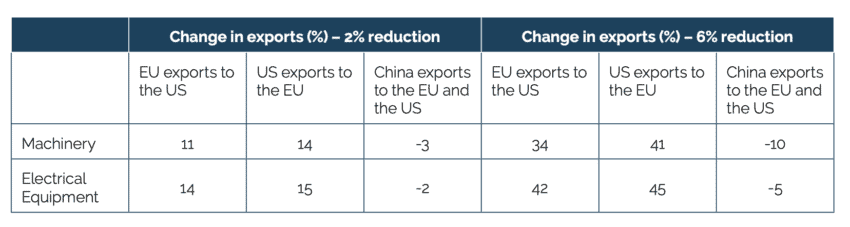

These mini deals can encompass many different sectors but let us – for the purpose of evidencing how important mini deals can be – focus on one example of a possible mini deal: an extension of the MRA on conformity assessment with the EU and the US. For instance, current trade in the machinery and electrical equipment sector between the two partners amounted to US$ 192 billion in 2022. Estimates over the trade-cost reductions for MRAs covering conformity assessment suggest that they reduce trade costs between 2 and 6 percent. This is significant.[10] In reducing regulatory costs, MRAs and mini deals more generally, are essential components of a sound market access strategy. They allow for non-discriminatory trade creation benefitting EU firms willing to export as well foreign companies seeking access to the Single Market.

The first effect, then, from a mini deal between the EU and the US along the above lines would be that Transatlantic trade costs are reduced and that they trade more with each other. The other effect is that it would reallocate some existing trade with third countries. Obviously, this can lead to sub-optimal forms of trade (i.e. the classic trade diversion effect) but it could also divert trade in a way that is correcting problems related to economic security. Hence, better conditions for Transatlantic trade in machinery and electrical equipment can lead to less trade dependence for the EU (and the US) on China.

Both results are strong and significant in our quantitative analysis of the economic effects from an extension of the EU-US MRA on conformity assessment in machinery and electrical equipment (see Table 2). Exports from the EU and the US to each other would go up significant – between 11 and 15 percent for the machinery and electrical equipment sectors if trade costs are reduced by 2 percent. In the scenario of a 6 percent reduction in trade costs, bilateral trade would go up by much more – up to a 42-45 percent expansion in bilateral exports in electrical equipment. The parallel development is that China’s exports in the two sectors (and China has a much larger share of the global market than both the EU and the US) to the EU and the US would decline. The size of the decline also depends on how much bilateral trade costs are reduced by the extension of the Transatlantic MRA.

Table 2: Economic effects of EU-US MRA on conformity assessment equal to a 2 and 6 percent reduction in trade costs, percentage change Source: ECIPE calculations (using GTAP).

Source: ECIPE calculations (using GTAP).

As this example shows, mini deals can contribute to enabling the competitiveness of EU companies. Mini deals should be used in particular in sectors with higher EU revealed comparative advantage – or sectors where there is strong potential for trade growth because of increasing regulatory costs. Sectors that fulfil these criteria are ICT sectors like telecom equipment and cybersecurity, “green” and cleantech sectors, and a whole range of services.

When employing mini deals, important elements to consider are to make use of renewal mechanisms, to keep up with the revisions of the legislation underpinning their functioning, to ensure proper MRA governance (e.g. annual meetings of the joint committees, regular updates of their legal scope) and to address regulatory challenges in areas where domestic developments across the globe lead to new regulatory requirements. As a result, the EU should also use mini deals to lead efforts for stronger global regulatory cooperation and spearhead more strongly global standard-setting as well as international standard alignment. This will help to prevent a new set of trade challenges for new non-tariff barriers if regulators around the world think in isolation.

3.4 Expand the Adequacy Framework for More Regulations

As we have already noted, reducing regulatory costs in trade is paramount for boosting exports and achieving a profile of imports that supports economic efficiency and security. While MRAs are especially important for sectors and relations that include substantial amounts of trade, there is also a strong opportunity to improve market access and resilience by other means of reducing the regulatory costs of trade. One general approach for the EU to do so is to establish or expand upon the already existing adequacy framework for privacy regulation.

When the European Commission adopts an adequacy decision, it “certifies that the data protection regime of the trading partner is equivalent to the EU.”[11] As a result, personal data can flow freely. This mechanism has proven beneficial for EU firms by facilitating their cross-border trade. Trade increased between 6 and 14 percent for countries that received EU adequacy – and this trade expansion, notably, is equally important for EU exports.[12] Until now, however, the EU has only included an adequacy mechanism in one area: the processing of personal data. The objective of an adequacy decision is to level the playing field in the processing of personal data between the EU and its trading partner, regardless of whether the processing takes place in the EU.[13]

Bridging between regulatory models is an effective way to reduce trade costs and administrative barriers. Moreover, sectoral standardisation across jurisdictions contributes significantly to competitiveness, especially in sectors where regulations play an important role for the total restrictions or the costs of trade. For example, since data transfers are a crucial input for many services that are likely to grow in importance, ensuring cross-border data portability needs now to be at the heart of cooperation between countries. Such cooperation has the potential to minimise trade costs with other countries already through internal design of EU regulations, thus addressing the market access and economic resilience problems outlined above.

Accordingly, the EU should expand on this adequacy model and create a clear and predictable “docking station” for countries to declare and acknowledge conformity with EU regulations. The EU is a global regulatory power and, for some time, has attempted to regulate faster and deeper than other comparable economies in a range of sectors, including data and digital sectors, and cleantech. Many other countries have shared the EU ambitions with regulation but not chosen the same approach or methodology as the EU. There are often a variety of reasons for why regulations between countries are different even if ambitions are similar: constitutional structures, industry and sector variations, and relations with other larger economies are common explanations.

As the EU share of the world economy goes down, it will find that fewer countries can follow the EU and imitates its regulations. However, they can find better ways to demonstrate to the EU that their regulatory structures and objectives are similar. A broad adequacy framework, offering other countries to dock their regulations with the EU, would lead to significant opportunities for the EU to expand its trade and avoid that increasing regulatory restrictions mean a reduction in trade.

3.5 Join the CPTPP

The EU should apply to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Early proposals by ECIPE scholars to this effect were met with two arguments. First, the EU is not a Pacific economy, and the CPTPP is designed to unite economies around that ocean. Second, the EU can achieve better market access by negotiation trade agreements bilaterally with CPTPP members. While there may be some merits to these arguments, they obviously have weakened over time.

The CPTPP may have started out as a Pacific initiative, but its character has changed. The US, the main initiator, decided to pull out of it. The UK has now applied to join, and the negotiations for the country’s accession started in the spring of 2023. China, Taiwan and South Korea have also applied to join. Just like the OECD started out as a forum for the Atlantic geography and then expanded with countries from other regions, the CPTPP is likely to become the most important agreement for wider trade policy arrangements for any country with an interest in intra or extra-Pacific trade. If Europe wants to continue shaping the terms and conditions that will evolve in global trade relations, it needs to complement its own policies with membership in region-wide fora.

The EU indeed has FTAs with many individual members of the CPTPP, but these individual arrangements do not contradict membership in the CPTPP. It is unlikely that membership in the CPTPP or future negotiation agenda will have a strong impact on trade liberalisation, but there is a market access agenda there that is important for certain sectors and the EU could reinforce it.[14] Moreover, there is a very strong resilience argument for joining the CPTPP to ensure that the key rules and conditions for open trade are maintained and improved.

There is also a geopolitical dimension in joining the CPTPP. China is by far the dominant economy in the pacific region. Although China’s accession is highly unlikely in the short term, its application for membership sends a geopolitical message. Other large economies need to be involved in regional efforts to counterbalance the Chinese influence in global trade. The withdrawal of the US from the CPTPP in 2016 left a power vacuum that can be regained by the EU as the largest western economic bloc.

Joining the CPTPP also offers the EU a unique opportunity to actively participate in shaping global digital trade norms and standards. Countries within the CPTPP framework are engaging in broader digital economy agreements—such as the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between New Zealand, Singapore, and Chile, and the Digital Economy Agreement between Australia and Singapore. Research shows that trade agreements with deep digital provisions, even when non-binding, significantly enhance digital-intensive trade between FTA partners. This is particularly true for provisions in areas like AI and the new data economy, which are becoming increasingly prevalent in modern trade agreements, especially in the Asia-Pacific region. These digital provisions not only address traditional trade issues but also pioneer commitments in emerging fields such as open government data, e-government, and data access for innovation.

3.6 Deepen TTCs with US and India

In 2021, the EU took ambitious steps to address geo-economic challenges through the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC). Despite other segments of the EU trade agenda remaining inactive, both parties committed to advancing trade in green technologies to accelerate the global green transition. The EU is a global leader in environmental technologies and it should leverage such a position in a productive cooperation with a strong trading partner like the US. Coordination also focused on facilitating transatlantic digital trade by eliminating administrative barriers and ensuring secure foreign investments. The TTC also addressed the critical issue of access to raw materials crucial for digital and environmental technologies.[15] Generally, the initiative aimed to focus on the important intersection of trade policy and rules, on the one hand, and fast-paced technological change, on the other hand.

While it is too early to fully review the usefulness of the EU-US TTC, it is clear that this format of talks and negotiations have underwhelmed many observers and that there are few real achievements to point to. There are many areas that are ripe for deeper Transatlantic cooperation – areas that have already been acknowledged and where there are not deep-seated protectionist policies keeping the two sides apart. For instance, it remains crucially important that both sides invest more in global standards development and protecting the institutions (including intellectual property rights, free markets, competition, and the role of independent courts and industry-driven standardisation processes) from attempts to exert stronger political control. Deeper coordination on production and trade rules for energy and raw materials, and for policies on energy security and raw materials access, is needed for both sides to individually improve on the current situation. Initiatives on global rules and standards on AI are needed beyond what has already been achieved.

Accordingly, the EU-US TTC should be enhanced, and Europe has a strong strategic interest to do so considering the risk of more political turbulence in Transatlantic relations in the next five years. The forum needs a more ambitious agenda. The EU-US TTC could be more consequential by broadening its scope and acting as a springboard for members to consult and implement common standards for trade, technology and economic security topics (for instance, cybersecurity policies and strategies). EU and US leaders could push forward new initiatives with objectives and priorities that can be met by a larger group of market-oriented economies that share the same core values regarding democracy and human rights.

The EU has also established a similar initiative with India. The EU and India conducted their first TTC meeting in May 2023, and the potential was immediately clear to everyone. India is a prominent trading partner for the EU: € 120 billion worth of goods were traded in 2022, of which € 17 billion were digital products.[16] India has become one of the largest technological hubs and has emerged as a leading pool for talent and sourcing within the technology sector globally. Likewise, it has consistently enjoyed a leadership position in its ability to establishing technology operations around the world.[17] India has emerged as important country in the services sector, too. Exports of ICT and Business Process services reached US$ 157 billion in 2021 and it is increasingly developing a highly skilled workforce in that sector.[18]

Still in its early phase, the EU-India TTC is deemed of high importance given the size of the combined markets and the possible synergies for EU firms, especially in digital sectors. There are both market access opportunities and chances to improve EU resilience. For this to happen, the EU needs dedicated leadership and a clear agenda for what it wants to achieve.

It is important to note that the EU-India TTC should not constitute a substitute for the EU-India FTA that is currently being negotiated. On the contrary, these two instruments could be mutually reinforcing. For the EU, it will be extremely important to have a robust and resilient institutional framework to maximise the benefits of a trade relationship with the world’s most populous democracy.

3.7 Deepen Neighbourhood Policies on Raw Materials

The European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) is the EU’s foreign policy programme for strengthening political and economic cooperation with its neighbouring countries. Its two main pillars are multilateral and bilateral agreements. The former is defined through overarching initiatives such as the Eastern Partnership (EaP), a forum that includes Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, and the Union for the Mediterranean (UfM), comprising the EU-27 and 16 Mediterranean countries.[19] In addition a significant step forward in increasing economic and trade integration in the region was reached with Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) with Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia in 2016. Obviously, now some of the EaP countries are about to start negotiating accession to the EU.

If there is one area where deepened policy cooperation through the ENP could deliver tangible results, it is for the project of diversifying imports of raw materials and energy. Close ties with countries in the region have already proven beneficial, especially given the objective of cutting imports of Russian gas by two-thirds by 2027. Azerbaijan agreed to increase gas supply to the EU, from 8.1 billion cubic meters in 2021 to at least 20 billion cubic meters by 2027, and in 2022 Algeria agreed to raise exports of gas to Italy by 40 percent.[20] [21] Many of the neighbourhood countries are rich in important minerals that the EU currently rely on China for, and where diversification is needed.

Unquestionably, the digital and green transition of the EU will depend on its capabilities to ensure a diversified and reliable mix of clean energy sources for which raw materials are critical. Looking at the EU’s closest allies, both in proximity as much as with values, must be one of the pillars of this strategy. In 2021, the EU signed a strategic partnership on raw materials with Ukraine. Ukraine holds deposits of 20 out of 30 raw materials critical for green and digital economies.[22] The EU-Ukraine partnership on raw materials is designed to work in three areas: (i) regulatory frameworks that address environmental and societal activities; (ii) development of raw materials and battery value chains, and (iii) encouragement of close cooperation in research and innovation.[23] Additionally, the EU has established partnerships with Canada, Kazakhstan and Namibia.[24]

While it is essential for Europe to gain access to CRM, the key opportunity lies in processing raw materials and the various stages of the value chain. The major challenge for the supply of these minerals and metals is not its geographical distribution but its market structure and for some of them, market concentration in processing is higher than in the extracting stage[25]. EU trade policy should be closely aligned by granting preferential access to its market for raw materials processed in neighbouring countries. Expanding the Neighbourhood Policy and linking it with policy instruments focused on the establishment of partnerships on raw materials as stated in the Commission New Growth Plan for the Western Balkans[26] is a step in the right direction.

There is no other region in the world that is better placed for the development of these partnerships than the countries of the EU’s immediate neighbourhood. The EU has a strong strategic interest to ensure that neighbouring countries are in its economic slipstream and that they have an interest to deepen investment in key strategic sectors that are of interest to Europe. For a long time now, the EU has dismissed and sometimes mismanaged relations to its neighbouring countries, and it is now time for improvement.

3.8 Initiate a Trade Resilience Coalition

A series of events in recent years have underscored the need for flexible but trustful arrangements of trade. Both the Covid-19 pandemic and the energy crisis following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine substantially stressed sourcing and supply chains, and exposed the EU as well as other countries to the risk of unpredictable and hugely distorting contingent trade policies (including export restrictions). Moreover, as more and more countries deepen their policies to reduce carbon emissions and green the economy, new risks and disruptions are emerging, exemplified for instance by the US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s Carbon-border Adjustment Mechanism.

In an ideal world, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) would be the forum where countries met to build trust and agree on rules on what can be done (and not be done) in a crisis or when a deep economic transformation is needed. However, this is not the case, and it is unlikely that the fortunes of the WTO are to be restored anytime soon. New leadership is needed to establish a framework to secure resilience in turbulent times.

One such initiative already exists. Founded in 2018, the Ottawa Group is composed of 13 WTO members (including the EU) to collaborate on the implementation of WTO reforms. It gained more attention in 2020 after a substantial backsliding of free trade in the health sector became evident during the Covid-19 pandemic.[27] The global scramble to secure medical goods exposed many supply chain vulnerabilities and was not only cost-inefficient[28] but also severely harming to global health.

Soon governments realised that these restrictions were preventing their own companies from exporting inputs which were imported as part of finished products[29]. Moreover, export restrictions were prone to generate retaliation from other countries, making it more difficult to source inputs and disincentivising companies from scaling up production. By advocating for trade facilitation measures, and even tariff removal on essential medical goods, the Ottawa Group largely contributed to upholding much-needed international cooperation in a time of crisis[30], facilitating trade and incentivising production of medical goods.

Considering the EU is increasingly confronted with geopolitically diverging power blocs, more sectors are starting to be harmed by protectionist policies. Just as the Ottawa Group illustrates for healthcare products, the EU should spearhead global cooperation in specific sectors deemed of common relevance and provide a structure allowing for the removal of unnecessary trade restrictions and the establishment of rules that govern trade behaviour in times of acute crisis.

These initiatives could be formed into a broader Coalition for Trade Resilience. Apart from building trust between members and agreeing on trade rules, members can also help prepare for common responses to sudden stresses in trade. For instance, if important trading routes become impossible to use, members will have an opportunity to address problems in more direct fashions[31].

An example of a such initiative would a Coalition for Trade Resilience in CRMs. This group can be formed by countries supplying or with reserves of CRMs and countries eager to reduce China’s global dominance in the mining and processing of these minerals and metals. The EU’s experience in its diversification away from Russian hydrocarbons offers a hopeful lesson for CRMs. Among the different strategies pursued to reduce Europe’s dependency on Russia, trade was the fastest and most cost-effective. The EU used global energy markets to its advantage, and already in 2022, Norway became the EU’s largest pipeline gas supplier.

Suppliers and buyers within the Coalition for Trade Resilience in CRMs could agree on policies to incentivise global mining and processing, and on disciplines to limit export restrictions. Similar ideas are currently pursued by the US (Minerals Security Partnership) or the EU (Critical Raw Materials Club, Strategic Partnerships, and Strategic Projects on CRMs) alone. An initiative that includes a larger group of countries will create a bigger market with fewer market barriers and price fluctuations, supporting a diverse and stable supply of CRMs necessary for the digital and energy transition.

[1] The European Parliament approved the EU-New Zealand Free Trade Agreement in November 2023, the EU-Chile Advanced Framework Agreement and its complementing deal on trade and investment liberalisation and the EU-Kenya Economic Partnership Agreement in February 2024.

[2] Council of the European Union. (2024). Global Europe: The value of free trade and fair trade. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/eu-free-trade/

[3] Source Mattoo, Aaditya; Rocha, Nadia; Ruta, Michele (2020). World Bank. These policy areas are: anti-corruption; competition policy; environmental laws; IPR; investment; labour market regulation; movement of capital; consumer protection; data protection; agriculture; approximation of legislation; audio visual; civil protection; innovation policies; cultural cooperation; economic policy dialogue; education and training; energy; financial assistance; health; human rights; illegal immigration; illicit drugs; industrial cooperation; information society; mining; money laundering; nuclear safety; political dialogue; public administration; regional cooperation; research and technology; SMEs; social matters; statistics; taxation; terrorism; and visa and asylum.

[4] These calculations excluded EU FTAs with Bosnia and Herzegovina; Moldova; and Ukraine which, as a stepping stone into EU membership, include 34, 32, and 29 legally enforceable policy areas outside the mandate of the WTO.

[5] The OECD does not report data for Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Malta, and Romania, which are EU27 Member States.

[6] Cernat, L. (2023). The Art of the Mini-Deals: The Invisible Part of EU Trade Policy. ECIPE. Available at: https://ecipe.org/publications/mini-deals-invisible-part-of-eu-trade-policy/

[7] Claussen, K. (2022). Trade’s mini-deals. Virginia Journal of International Law, 62(2),315-382

[8] Cernat, L. (2023). The Art of the Mini-Deals: The Invisible Part of EU Trade Policy. ECIPE. Available at: https://ecipe.org/publications/mini-deals-invisible-part-of-eu-trade-policy/

[9] González, J. L., Sorescu, S., & Kaynak, P. (2023). Of bytes and trade: Quantifying the impact of digitalisation on trade.

[10] Guinea, O., Sharma, V., Lamprecht, P., Pandya, D. & du Roy O. (2024). Calling on the EU-US Trade and Technology Council: How to Deliver for the Planet and the Economy. Report, ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 4/2024, 42 p.

[11] Ferracane, M., Hoekman, B., van der Marel, E. and Santi, F. (2023). Digital Trade, Data Protection and EU Adequacy Decision. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75629/RSC%20WP%202023%2037_V5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[12] Ferracane, M., Hoekman, B., van der Marel, E. and Santi, F. (2023). Digital Trade, Data Protection and EU Adequacy Decision. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75629/RSC%20WP%202023%2037_V5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[13] Regulation (EU). 2016/679 of the European Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council. Art. 3. (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2016.119.01.0001.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2016%3A119%3ATOC).

[14] Kommerskollegium. (2023). The need for enhanced EU cooperation with the CPTPP. Available at: https://www.kommerskollegium.se/en/about-us/conferences-and-seminars/webinar-eu-trade-integration-with-the-asia-pacific/the-need-for-enhanced-cooperation-with-the-cptpp/

[15] European Commission. (2024). EU-US Trade and Technology Council. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-us-trade-and-technology-council_en

[16] European Commission. (2023). First EU-India Trade and Technology Council focused on deepening strategic engagement on trade and technology. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_2728

[17] See: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/in/Documents/strategy/in-s-o-emerging-technology-hubs-of-india-19.12-final-noexp.pdf

[18] EY. (2023). How India is emerging as the world’s technology and services hub. Available at: https://www.ey.com/en_in/india-at-100/how-india-is-emerging-as-the-world-s-technology-and-services-hub

[19] EEAS. (2021). European Neighbourhood Policy. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/european-neighbourhood-policy_en

[20] European Commission. (2022). EU and Azerbaijan enhance bilateral relations, including energy cooperation. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_4550

[21] Reuters. (2022). Italy clinches gas deal with Algeria to temper Russian reliance. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/italy-signs-deal-with-algeria-increase-gas-imports-2022-04-11/

[22] EU Commission (2022) EU – Ukraine strategic partnership on raw materials: the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development will support digitalisation of geological data in Ukraine. Available at: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-ukraine-strategic-partnership-raw-materials-european-bank-reconstruction-and-development-will-2022-11-17_en

[23] EU Commission (2021) EU and Ukraine kick-start strategic partnership on raw materials. https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-and-ukraine-kick-start-strategic-partnership-raw-materials-2021-07-13_en

[24] EU Commission (2023) Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and amending regulations (EU) 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52023SC0161

[25] Righetti, E. and Rizos, V. (2023) The EU’s Quest for Strategic Raw Materials: What role for Mining and Recycling? InterEconomics: Review of European Economic Policy. Vol. 53(2). Available at: https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2023/number/2/article/the-eu-s-quest-for-strategic-raw-materials-what-role-for-mining-and-recycling.html

[26] European Commission (2023). New growth plan for the Western Balkans. COM(2023) 691 final.

[27] Government of Canada. (2023). WTO Reform: Canada and the Ottawa Group. Available at: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/wto-omc/ottawa-group-groupe.aspx?lang=eng

[28] OECD (2020). Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods. OECD, Paris.

[29] In the case of the EU see: European Commission (2020, May 26). Coronavirus: Requirement for export authorisation for personal protective equipment comes to its end. European Commission, Retrieved from https://trade.ec.europa.eu .In case of the US see: The US Administration considered to ban exports to Canada and Mexico of respirators made by 3M but finally decided not to impose those measures (Bollyky, T., & Bown, C. 2020).

[30] Government of Canada. (2023). WTO Reform: Canada and the Ottawa Group. Available at: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/wto-omc/ottawa-group-groupe.aspx?lang=eng

[31] Davison, J., & Stewart, P. (2023, December 18). Red Sea attacks force rerouting of vessels, disrupting supply chains. Reuters, Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/red-sea-attacks-force-rerouting-vessels-disrupting-supply-chains-2023-12-18/

4. Conclusion

Lagging trade policy has contributed to Europe’s increasing detachment from the global economy. Europe’s reduced engagement with the rest of the world can be explained by two economic hurdles: market access and economic resilience. These two problems stifle trade’s potential to boost Europe’s competitiveness, impacting job growth and innovation, and lower its economic dependencies.

Over the next five years, the European Commission must urgently steer Europe’s trade policy ship towards greater market access and economic resilience. Failure to act will limit the EU’s economic potential and leave it vulnerable to global disruptions. This Policy Brief outlines seven realistic policies that will decisively contribute to better market access and economic resilience for the EU economy, fostering greater competitiveness.

- Modernise existing FTAs and conclude agreements with Mercosur, Australia and the ASEAN countries: update current FTAs and reach new agreements with Mercosur, Australia and some of the ASEAN countries such as Indonesia, Thailand or the Philippines.

- Negotiate “Mini deals”: prioritise sectoral agreements in areas where global regulatory requirements diverge and in sectors where the EU demonstrates a comparative advantage.

- Expand the adequacy framework for regulation: develop a transparent and efficient process for countries to demonstrate alignment with EU regulations.

- Join the CPTPP: the EU should apply to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to shape trade rules and counter Chinese influence in the region.

- Deepen Trade and Technology Councils (TTCs) with US and India: the EU-US TTC should be broadened and serve as a springboard for consultation and implementation of new trade and technology policies. Moreover, the EU should elevate the EU-India TTC recognising India’s growing importance as a tech hub and talent pool.

- Deepen Neighbourhood Policies on raw materials: leverage the Eastern Partnership and the Union for the Mediterranean to secure a reliable and sustainable supply of critical raw materials.

- Initiate a trade resilience coalition: building upon the Ottawa Group’s, the EU should spearhead the creation of a Trade Resilience Coalition.

References

Bollyky, T. J., & Bown, C. P. (2020). The tragedy of vaccine nationalism: only cooperation can end the pandemic. Foreign Aff., 99, 96.

Cassiman, B., Golovko, E., & Martínez‐Ros, E. (2010). Innovation, exports and productivity. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 28, 372-376. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJINDORG.2010.03.005.

Cernat, L. (2023). The Art of the Mini-Deals: The Invisible Part of EU Trade Policy. ECIPE. Available at: https://ecipe.org/publications/mini-deals-invisible-part-of-eu-trade-policy/

Claussen, K. (2022). Trade’s mini-deals. Virginia Journal of International Law, 62(2),315-382

Council of the European Union. (2024). Global Europe: The value of free trade and fair trade. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/eu-free-trade/

Criscuolo, C., & Timmis, J. (2017). The relationship between global value chains and productivity. International Productivity Monitor, 32, 61-83.

Criscuolo, C., Gal, P. N., & Menon, C. (2017). Do micro start-ups fuel job creation? Cross-country evidence from the DynEmp Express database. Small Business Economics, 48, 393-412.

Davison, J., & Stewart, P. (2023, December 18). Red Sea attacks force rerouting of vessels, disrupting supply chains. Reuters, Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/red-sea-attacks-force-rerouting-vessels-disrupting-supply-chains-2023-12-18/

Del Giovane, C., J. Ferencz and J. López González (2023), “The Nature, Evolution and Potential Implications of Data Localisation Measures”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 278, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/179f718a-en

EEAS. (2021). European Neighbourhood Policy. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/european-neighbourhood-policy_en

Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Lamprecht, P., Sharma, V., & Zilli Montero, R. (2022). The new wave of defensive trade policy measures in the European Union: Design, structure, and trade effects (ECIPE Occasional Paper 4/2022). European Centre for International Political Economy.

Erixon, F., Guinea, O., Van der Marel, E., and Sisto, E. (2022) “After the DMA, the DSA and the New AI regulation: Mapping the Economic Consequences of and Responses to New Digital Regulations in Europe” ECIPE Occasional Paper No. 3/2022

EU Commission (2021) EU and Ukraine kick-start strategic partnership on raw materials. https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-and-ukraine-kick-start-strategic-partnership-raw-materials-2021-07-13_en

EU Commission (2022) EU – Ukraine strategic partnership on raw materials: the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development will support digitalisation of geological data in Ukraine. Available at: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-ukraine-strategic-partnership-raw-materials-european-bank-reconstruction-and-development-will-2022-11-17_en

EU Commission (2023) Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and amending regulations

European Commission (2020, May 26). Coronavirus: Requirement for export authorisation for personal protective equipment comes to its end. European Commission, Retrieved from https://trade.ec.europa.eu

European Commission (2023). New growth plan for the Western Balkans. COM(2023) 691 final.

European Commission. (2022). EU and Azerbaijan enhance bilateral relations, including energy cooperation. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_4550

European Commission. (2023). First EU-India Trade and Technology Council focused on deepening strategic engagement on trade and technology. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_23_2728

European Commission. (2024). EU-US Trade and Technology Council. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-us-trade-and-technology-council_en

Ferracane, M., Hoekman, B., van der Marel, E. and Santi, F. (2023). Digital Trade, Data Protection and EU Adequacy Decision. Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/75629/RSC%20WP%202023%2037_V5.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

González, J. L., Sorescu, S., & Kaynak, P. (2023). Of bytes and trade: Quantifying the impact of digitalisation on trade.

Government of Canada. (2023). WTO Reform: Canada and the Ottawa Group. Available at: https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/wto-omc/ottawa-group-groupe.aspx?lang=eng

Guinea, O., & Forsthuber, F. (2020). Globalization comes to the rescue: How dependency makes us more resilient (No. 06/2020). ECIPE Occasional Paper.

Guinea, O., Sharma, V., Lamprecht, P., Pandya, D. & du Roy O. (2024). Calling on the EU-US Trade and Technology Council: How to Deliver for the Planet and the Economy. Report, ECIPE, Brussels, Policy Brief 4/2024, 42 p.

IMF. IMF World Economic Outlook 2023.

Kommerskollegium. (2023). The need for enhanced EU cooperation with the CPTPP. Available at: https://www.kommerskollegium.se/en/about-us/conferences-and-seminars/webinar-eu-trade-integration-with-the-asia-pacific/the-need-for-enhanced-cooperation-with-the-cptpp/

Mattoo, A., Rocha, N., & Ruta, M. (Eds.). (2020). Handbook of deep trade agreements. World Bank Publications.

Melitz, M. (2003). The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica, 71, 1695-1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00467.

OECD (2020). Trade interdependencies in Covid-19 goods. OECD, Paris.

Regulation (EU). 2016/679 of the European Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council. Art. 3. (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2016.119.01.0001.01.ENG&toc=OJ%3AL%3A2016%3A119%3ATOC

Reuters. (2022). Italy clinches gas deal with Algeria to temper Russian reliance. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/italy-signs-deal-with-algeria-increase-gas-imports-2022-04-11/

Righetti, E. and Rizos, V. (2023) The EU’s Quest for Strategic Raw Materials: What role for Mining and Recycling? InterEconomics: Review of European Economic Policy. Vol. 53(2). Available at: https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2023/number/2/article/the-eu-s-quest-for-strategic-raw-materials-what-role-for-mining-and-recycling.html

Salomon, R., & Shaver, J. (2005). Learning by Exporting: New Insights from Examining Firm Innovation. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 14, 431-460. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1530-9134.2005.00047.X

(EU) 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52023SC0161

Annex

Figure 1: Development of intra-EU and extra-EU goods and services exports, 2014-2021, in EUR BN Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Figure 2: Share of Extra-EU exports and intra-EU exports to EU’s GDP, 2012-2022 Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Figure 3: Number of Non-Tariff Barriers affecting EU firms, 2009-2023 Source: Global Trade Alert, ECIPE calculation. NTB implemented by the EU are excluded.

Source: Global Trade Alert, ECIPE calculation. NTB implemented by the EU are excluded.

Figure 4: Shifts in the EU’s Revealed Comparative Advantage across various economic sectors Source: TiVA 2023; ECIPE calculation.

Source: TiVA 2023; ECIPE calculation.

Figure 5: The EU’s trade in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) services, 2010-2020, in billion EUR Source: OECD, ECIPE calculation. Figures deflated to 2020 prices.

Source: OECD, ECIPE calculation. Figures deflated to 2020 prices.

Figure 6: EU-US trade in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) services, 2018-2020, in billion EUR Source: OECD TiVA, ECIPE calculation. Figures deflated to 2020 prices.

Source: OECD TiVA, ECIPE calculation. Figures deflated to 2020 prices.

Figure 7: EU import dependency in goods, by product type (2022) Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Figure 8: Highly dependent products categories, by import value and category count of products (CN codes) Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Figure 9: Origin of EU imports of strategic raw materials in 2022 (in terms of volume) Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Figure 10: The share of inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) relative to the EU’s GDP Source: OECD and Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.

Source: OECD and Eurostat, ECIPE calculation.