Published

The Coming Trump Tariff Deadline: Mapping Globalisation and Trade Fragmentation

By: Oscar du Roy

Subjects: North-America WTO and Globalisation

Is global trade about to be so bruised we can no longer talk about a global economy? As we’re getting close to the deadline for the Trump tariff deals, it’s only natural that the question is asked. Every government fears a new round of tariff assaults by the US but no one really knows what will happen – what level of tariffs that the US will impose on countries or if there are going to be trade deals that take away all “Liberation Day” tariffs. For the EU, there has been a brief pause, as the tariff implementation originally scheduled for June 1 was postponed until July 9, and it may be pushed to August 1 to allow more time for negotiations. However, it has become increasingly clear that, aside from a deal with Britain, the administration won’t achieve the Trumpian target of ’90 deals in 90 days’.

Adding to this uncertainty, a federal trade court ruled in late May that some of Trump’s tariffs were unlawful and needed Congressional approval. A negative ruling by a federal appeals court would not only damage the credibility of US foreign economic policy but also reduce the chances that the Trump administration can squeeze more favours out of other countries by threatening punitive-level tariffs. If tariffs are hiked, the global economic repercussions could be significant.

But are the Trump tariffs an existential moment for global trade? They don’t seem to be. Despite their damage the alarmist claims that the entire global trading system is in danger of unravelling are, at least for now, exaggerated. This blog is a preamble to a larger ECIPE study to be published in September. It will explore four key developments that suggest trade remains remarkably resilient, even in the face of escalating geopolitical tensions and tariffs. We’ll take a closer look at how trade flows have adjusted to recent geopolitical shifts, the role of strategic technology restrictions, and the evolving fragmentation of global trade – not as a collapse, but as an adaptation.

Globalisation Isn’t Dying, It’s Simply Changing

It is often suggested that the world trade has tanked or deglobalized because of major international macroeconomic shocks. First in the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, then during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and now amid escalating geopolitical tensions. This is not a good account of what actually has happened. Global trade is not declining (i.e., deglobalisation), it is rather slowing down – and, importantly, evolving.

At the macro level, the data on global trade volumes for goods and services does not show a downward average trend. What has changed is its pace of growth and composition. Since 2011, global goods exports have grown more slowly – averaging about 1.5 percent annually compared to over 10 percent in the decade before. It follows a uniquely dynamic period in which trade was turbocharged by containerisation, the ICT revolution, and the opening of major economies to global markets (notably China). There is at best a slowdown in trade growth, but it continues to grow.

At the same time, trade has increasingly moved from physical goods toward services, intellectual property, and digital content – flows that are harder to measure but that are just as global and important. The structure of globalisation is shifting toward intangibles: services now make up over 80 percent of global Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), up from just two-thirds in the early 2000s. This shift has reduced the need for traditional capital-intensive investments abroad, while expanding the role of cross-border data, knowledge, and services. Thus, from the perspective of FDI there is a visible downward trend, though it’s largely due to the expansion of services trade globally.

There’s also a compositional story: larger, advanced economies tend to export at slower rates than smaller or emerging ones, which contributes to a deceleration in overall growth. Moreover, the structure of global trade now reflects a greater diversity of products and origins, with higher growth in processed goods and digital services than in traditional manufacturing or raw materials. In short, globalisation is not receding, it is evolving, driven by services and intangibles.

The Rise of Strategic Trade Exclusion

Bilateral exchange between major trading regions is fragmenting. This is not a case of systemic decoupling or the formation of isolated economic blocs, but rather a targeted and politically driven process through bilateral trade exclusion. The most prominent examples are the US-China trade war and the EU’s decoupling from Russia because of economic sanctions. These measures have substantial economic consequences due to the scale of the affected trade, but they have not caused an overall decline in global trade volumes. Instead, they have triggered a redistribution of trade flows, as countries and firms adapt to the new constraints.

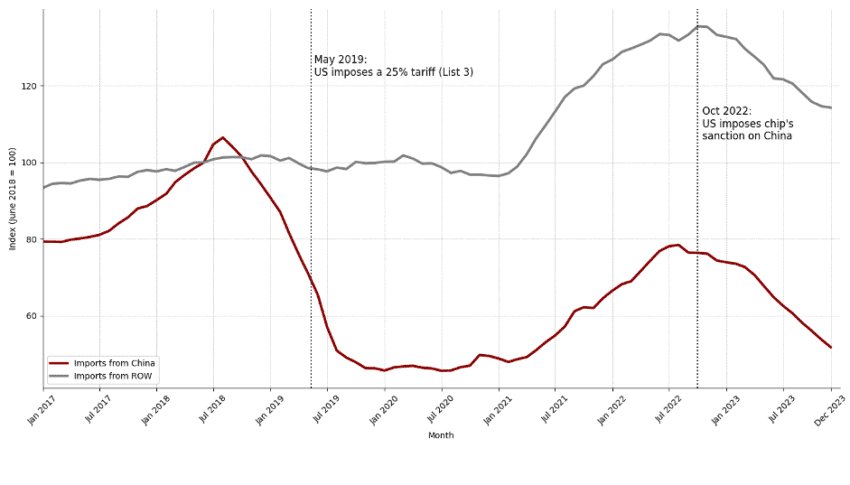

Bilateral trade exclusion occurs when two countries intentionally reduce their economic interdependence, usually through tariffs, export controls, investment screening, or regulatory barriers. The most straightforward instance is the US-China trade war, which began in 2018 with targeted tariffs and export restrictions on goods in key sectors like semiconductors, electronics, and green technologies. As shown in Figure 1, following the initial round of tariffs in August 2018, U.S. imports of semiconductors from China fell by more than 40 percent within a year, illustrating the immediate and significant impact of the trade restrictions on affected products.

Figure 1: US imports of semiconductors from China and the rest of the world (ROW), (index, June 2018 = 100) Source: ECIPE calculations; USITC; Bown (2022); USTR.

Source: ECIPE calculations; USITC; Bown (2022); USTR.

While tariffs can profoundly reduce bilateral trade in targeted goods and impose negative welfare effects domestically, they have not triggered structural shifts in the global trading system. Instead, trade flows have been reallocated, where production capacities exit to serve as substitutes. In the case of the US-China trade war, this meant a diversion of US imports away from China toward third countries.[1] Vietnam offers a clear example: US imports from Vietnam more than doubled between 2018 and 2023, rising from approximately $47 billion to over $114 billion. As for China, its position in global trade remained resilient; its share of global merchandise exports increased from 12.6 percent in 2018 to 14.1 percent in 2023.[2]

A World Divided, but Not Disintegrated

An alternative way to frame the question of trade fragmentation is to ask whether trade is reorganising along geopolitical lines. This form of geoeconomic fragmentation is not just about isolated country pairs imposing tariffs, it’s about blocs gradually reorienting their trade relationships based on strategic alignment, security priorities, and trust.

In our main study, we identify three main blocs. The Western bloc, centred around the US, EU, and UK, which still dominates global exports, accounting for 41 percent of global exports in 2024, but its share is gradually declining. The Eastern bloc, led by China and Russia, has increased its share from 9 percent in 2002 to 17 percent today. In between lies a pivotal Neutral or “swing” bloc of countries: India, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, and others, that are neither fully aligned. These economies are becoming the key channels of trade redirection.

This realignment is most visible in the trade flows between the Eastern and Western blocs. Since 2002, the share of exports from the East to the West has fallen from 52 percent to 40 percent. The decline accelerated after two flashpoints: the US-China tariffs in 2018 and the EU’s decoupling from Russia in 2022. At the same time, Eastern bloc exports to the Neutral bloc surged, rising from 25 percent in 2021 to 35 percent in 2024, nearly matching their exports to the West. In short: as trade ties between the West and East weaken, the middle is absorbing the residual flows.

Trade flows from the Western bloc tell a similar story. Exports to the East dropped from 8 percent to 5 percent between 2021 and 2023, while exports to Neutral countries rose sharply to 21 percent in 2024. These aren’t isolated shifts; they reflect a deliberate diversification strategy. In particular, countries like Mexico, Vietnam, and Canada have gained market share in both U.S. and Chinese imports, suggesting that indirect trade via third countries is becoming a feature of the new global order.

The international trade system is not entirely polarised along geopolitical lines, but there are emerging patterns suggesting trade is flowing differently. On top of the classical drivers of trade flows – cost and firm specialisation – strategic trust, geopolitical considerations, and supply chain resilience seem to be playing an important role in favour of the Neutral bloc.

Conclusion

As the world awaits the outcome of the July 9th, or August 1st, tariff decisions, few certainties exist about how global trade will re-organise with universal tariffs. We know that bilateral tariffs have historically led to trade diversion toward third countries, often with measurable negative consequences, but global or multi-country measures introduce more unpredictable dynamics. Will this next round of tariffs further accelerate the shift toward a Neutral bloc of economies? Will technology and digital regulation become even more central in shaping trade patterns, beyond goods and commodities? And how might firms and governments respond if the strategic separation between major blocs continues to widen? These questions will shape not only the immediate fallout of the tariffs but also the longer-term structure of global trade.

What we observe already is that globalisation is not reversing but changing shape. Trade flows have become more geographically dispersed and more focused on services and intangibles. Fragmentation is real, but it is selective: targeted exclusions between major economies rather than systemic breakdown. Neutral economies such as India, Vietnam, and Mexico are becoming more important as trade re-routes around points of political tension. While overall trade growth has slowed, the system remains adaptive. Fragmentation and globalisation are not mutually exclusive; they now exist in parallel.

[1] Fajgelbaum, Pablo, Pinelopi Goldberg, Patrick Kennedy, Amit Khandelwal, and Daria Taglioni. 2024. “The US-China Trade War and Global Reallocations.” American Economic Review: Insights 6 (2): 295–312. DOI: 10.1257/aeri.20230094

[2] https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators/Series/TX.VAL.MRCH.CD.WT#advancedDownloadOptions