Published

Trade Retaliation – An Answer Waiting for Its Question

By: Fredrik Erixon

Subjects: European Union North-America

A question that is haunting the EU and other key trading partners of the United States is whether they should retaliate against Trump’s tariff assault. So far, the EU’s response to the Trump tariff assault has been reasonably calm, seeking a dialogue that eventually may have a positive effect on what levels of tariffs that will be applied by the US in the future. It has also signalled that it is designing a retaliation proposal that could go live if negotiation prove fruitless. Most other countries have taken the same attitude: let’s talk and negotiate first, and postpone any retaliatory measure until a later date.

Obviously, China has retaliated and, even after the exemptions on some tech and electronics goods, the US and China are locked in a tariff war that will have huge consequences on their trade. For sure, the chaos in their bilateral trade will have consequences for how other countries trade with the US and China. As a result, we are not just talking about one tariff event anymore (Trump’s tariff package): the world economy is going to reorient itself in the coming months and years, and it will impact the broad economy as well as international relations.

It is also a cautionary tale for other countries, and I am going to outline in this piece why I believe it is important for the EU to remain calm and not rush to retaliation. I noticed that Thierry Breton has recently been out arguing for a strong EU retaliation. He is not the first one, of course, and like some others he seems to be suggesting that EU should already have retaliated. Others still are gushing the EU into using its new Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) and target for instance services and intellectual property flows – for reasons that are mostly related to achieving volume parity in trade injury and inflicting greater economic and political damage on the US.

Still, I have not heard any of the supporters of retaliation providing a motivation for action that goes beyond retribution and, perhaps, some other base instincts. But for retaliation to make sense in the first place, it needs a “model of action” or a “model of thinking” that also include an understanding of what the retaliation is supposed to achieve. No doubt the EU could inflict economic damage on the US export sector. The problem is that retaliation would also inflict damage on the EU economy – and if the EU seeks retaliation that achieves comparative injury on trade, the damage on the EU economy is likely to be bigger than the injury suffered by the US. Moreover, if the EU retaliates, there are obvious risks of escalation – “retaliation equals escalation”, as consultants in anger management will tell you. What should the EU do if the US hits back even harder? Escalate even more? I have yet to see someone laying out the plausible scenarios. Supporters of retaliation at least owe us clarity on their thinking: what is the outcome you seek for which retaliation is the best strategy?

Most informed observers – regardless of where they stand on trade issues – would probably agree that what is important now is that EU builds a response that reflect its own economic and political interests. In my view, this interest now stands in opposition to retaliation, including the use of retaliatory trade restrictions in non-tariff areas like services and intellectual property. Matters may change, however, depending on how Trump’s attack on the US economy, global exporters, and world order will unfold. For now, there are four arguments against retaliation by the EU.

1. European Security

It’s notable that concerns over European security have not featured much in the public European debate about retaliation. However, it weighs heavily on the minds of some EU countries – especially countries with closer proximity to Russia and who are, more than other EU countries, exposed to the security risks in the changing European security order. Even if one discounts matters of nuclear weapons, it is abundantly clear that Europe does not have the capacity to fight wars in its own region without the aid of the United States. Therefore, it can be assumed that Europe does not have the capability to adequately deter aggressors either, if the US is taken out of the picture. It is going to take a long while for Europe to build capacity and deterrence – despite recent moves in Germany, Brussels, and elsewhere to commit new resources for defence. Some European leaders have been suggesting a timeframe of 3-5 years for the US to pull significant troops and capacity out of Europe, allowing for a phased expansion of autonomous capacity in Europe.

The question is: could US defence commitments to and capacity in Europe be thrown into a scenario of an escalating bilateral trade war? Some seem to think this is not the right way of thinking about a trade war. Perhaps it isn’t. A supporting argument for this view is that the EU has sparred with the US in the past (even with President Trump) on trade without EU actions leading the US pulling security guarantees or acting in ways that compromise European integrity and interests. This happened during the first Trump administration, for instance. Nor were there any escalation by the White House pointing in the direction of security policy when the EU recently decided on a retaliation against Trump’s new tariffs on steel and aluminium. Additionally, while Trump as commander in chief may decide not to intervene if a NATO ally is attacked, he cannot pull the US out of NATO without Congressional support.

And yet… Should Europeans really take the risk? Is it clear – I mean, really clear – that Trump won’t make security guarantees and military aid part of an escalating trade war with Europe? I think not. In my view, it is obvious that President Trump is unreliable and that there are few – if any – around him with the power to control his impulsive nature and fractious thoughts. He trades hard-won, long-term strategic US gains for small tactical rewards – and seems to think he is “winning” if he controls the news agenda. Just as Europe cannot build a security relation on the basis of such a leader, it should observe the risk that Trump will compromise European security, if he thinks there is something in it for him. As long as Europe’s security dependency lasts, it will have limited space for actions on trade.

The likely scenario for a trade war is that it will run for a long time: retaliation cannot build on the assumption that strong retaliation by the EU would end trade frictions and US tariffs. A new war in Europe may not look likely now, but a lot can happen over the next four years. After all, the Trump administration cut Ukraine off from access to intelligence, showing its lack of restraint and judgment when it is facing opposition from a partner country. Likewise, it has threatened Ukraine with the denial of access to Starlink. Trump obviously has a hang-up on Europe, which he thinks is a region of spongers and freeloaders. Indeed, he seems to think the EU was established to “screw” the United States. He and his administration had no second thoughts about cutting Europe out from initial talks with Russia over a standstill or peace agreement, knowing how threatening that an agreement with Russia could be for future security in Europe. Claims that the US may take over Greenland may not be hundred percent sincere, but they are sincere enough for Europe to prioritise national security and avoid provoking the country that provides for its security.

Europe should focus now on new defence and resource plans that are credible and that can form the basis of a medium-term defence deal with the US that is also attractive for the Trump administration. An important NATO summit is planned for June 24-25. Before that, most European NATO members should develop real policies to plug the gap between actual defence resources and needs, not least reflecting the new cycle of NATO’s defence planning process that will usher in demands of new operational capacities. The summit is an opportune moment for Europe to show it is serious about strategic autonomy. The summit is also concentrating minds in Washington, DC and, ideally, Europe would invest enough trade patience to protect the procedural integrity of NATO and defence planning.

2. Avoiding Economic Turbulence in Europe

As everyone could observe the week following the tariff announcement, the climb in US bond yields (especially for the 10-year Treasury bond) was a warning about the state of the US economy. As I then wrote in a piece, Trump’s tariff assault has affected trust in US economic institutions, leading among other things to a falling US dollar and greater recession risks. Markets and other observers listen to what administration folks are saying about their long-term macro ambitions: they don’t like the message.

What Europeans like Valéry Giscard d’Estaing once said was an “exorbitant privilege” – having the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency – is seen by many in the administration to rather be an exorbitant burden. In their view, the exchange rate cannot help to correct for deficits in the trade balance. Now, however, they want to engineer a change while the US federal government sits on 36 trillion in public debt and is highly dependent on net inflows of capital. Markets fear that the Trump administration will try to unplug the US from global economic leadership, and administration’s tariff charlatanism became a harbinger of the chaotic school of economic management also being applied to broader macroeconomic challenges.

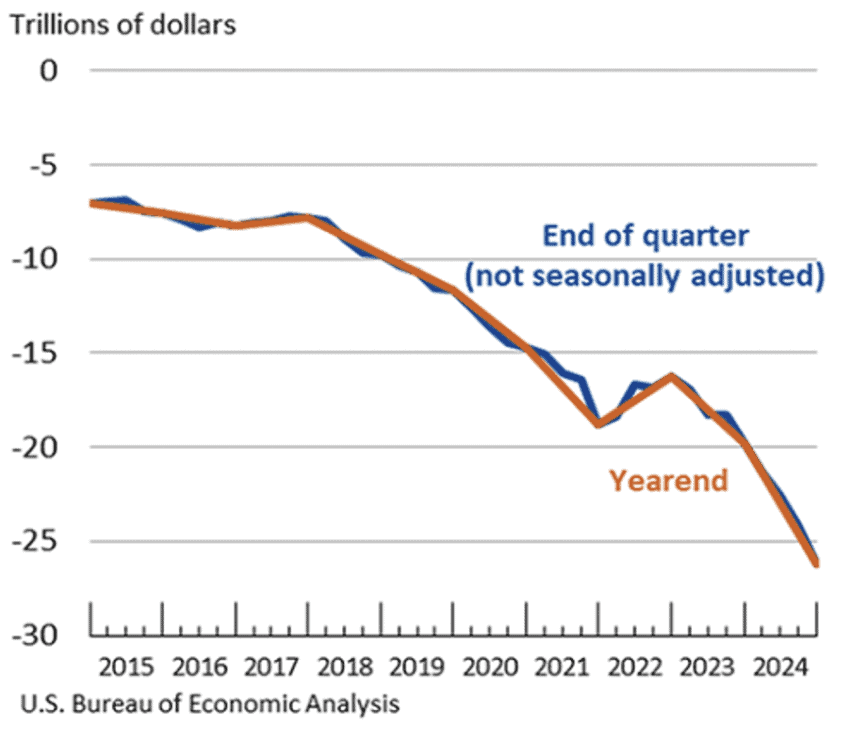

Markets should be concerned. One way to understand the reaction to the tariff package is to consult the US Net International Investment Position (see figure from the BEA below: the US NIIP by the end of Q4 2024), a measure of a country’s external assets and liabilities. It’s a balance sheet, so to say, over a country’s economic relation with the world. The US NIIP has had a remarkable development over the last ten years. Investments by foreigners in US held debt has expanded a lot and the US had a net position of -27 trillion US dollars by the end of last year. Obviously, the development speaks to the attractiveness of the US investment market – but it also shows a country that cannot finance itself and that needs to attract substantial amounts of capital from abroad. US public debt is part of the story, but the share of US treasuries held by foreigners has gone down in the past 15 years and stands at around one third of total public debt (here’s a good essay on US debt holding). Generally, however, the US economic model has developed to become very dependent on access to foreign investors.

Chart 1: US net international investment position

In plain speak, the general US dependency on foreign investors is unsustainably high and it is alarmingly high for a country bent on changing its economic relation with the world while controlling the world’s pre-eminent currency. While it is correct that the US economy has fundamental problems with key balances (the fiscal balance, savings-consumption balance) the reality is that its NIIP makes it very vulnerable to changes in key factors for the valuation of liabilities. A depreciation of the US dollar will have disproportionate effects on the economy because so much of the debt will get re-valued – and, for the US government, it adds to the additional capital costs for its public debt that is represented by higher bond yields. With strong outflows of capital, the US will have to pay more for its big liabilities.

In plain speak, the general US dependency on foreign investors is unsustainably high and it is alarmingly high for a country bent on changing its economic relation with the world while controlling the world’s pre-eminent currency. While it is correct that the US economy has fundamental problems with key balances (the fiscal balance, savings-consumption balance) the reality is that its NIIP makes it very vulnerable to changes in key factors for the valuation of liabilities. A depreciation of the US dollar will have disproportionate effects on the economy because so much of the debt will get re-valued – and, for the US government, it adds to the additional capital costs for its public debt that is represented by higher bond yields. With strong outflows of capital, the US will have to pay more for its big liabilities.

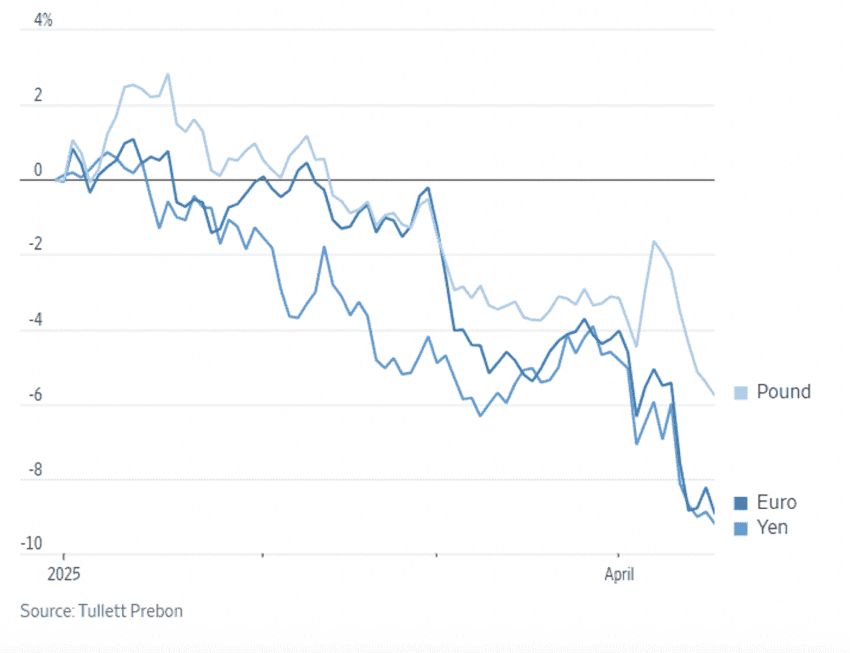

So what has Europe got to do with all this? Well, it is already caught up in the market turbulence. Stocks in Europe have tanked too. The euro and other European currencies have appreciated a lot against the US dollar in 2025 (see figure below for USD depreciation against the euro, the yen, and the pound). The dollar lost 5.5 percent of its value against the euro in just one week after the tariff announcement. It appreciated, at first, against some smaller currencies, but as the uncertainty connected to US bonds and stocks increased, the dollar continued depreciating also against them. If the development continues with a weakening dollar, bigger capital flows into the Eurozone, and a weakening business cycle export sales and corporate earnings in Europe will be impacted substantially. European exports, for instance, will become more expensive, leading to stronger pressures on economic activity in especially surplus countries like Germany. Disinflation pressures will become stronger, possibly affected by a China that may look to depreciate the Yuan. The good news is: we may not need to worry anymore about high inflation. And the bad news? The Eurozone may soon again face so strong disinflation pressures that we have to worry again about deflation risks.

Chart 2: US dollar performance this year against major currencies

Changes in America’s trade and financial relation to the world will strongly impact on the European economy – in the long as well as the short-term. The issue of trade retaliation is important in the short term because it may provoke more macroeconomic and market turbulence, and push Europe to import even more of the turbulence from the US. The European Central pointed to these risks in its Maundy Thursday policy statement: “Deteriorating financial market sentiment could lead to tighter financing conditions, increase risk aversion and make firms and households less willing to invest and consume.”

In a scenario of trade retaliation, and the attendant risks of escalation, Europe should be concerned with general credit deleveraging in Europe and effects on the corporate bond market – two important levers of economic activity in the European economy. Trade retaliation that is on par with the US tariff coverage on EU exports will have to cover a lot of trade and will have negative impacts on the EU economy. Undoubtedly, the result would be more uncertainty.

More specifically, Euro Area concerns are also specific to unsustainable levels of fiscal deficits and public debt. Yields on European government bonds with 10-year maturity have climbed a lot since December last year. They have come down since Trump’s tariff announcement but remains high. The IMF has just pointed to the obvious, that the tariffs and ensuing economic and political risks will force everyone to revaluate conditions for financial stability, including new demands on financial institutions to hold bigger buffers as asset values are declining. Given where we stand now in terms of market uncertainties, Europe needs to be very careful not to stoke more global uncertainty and make the region a stronger source of turbulence.

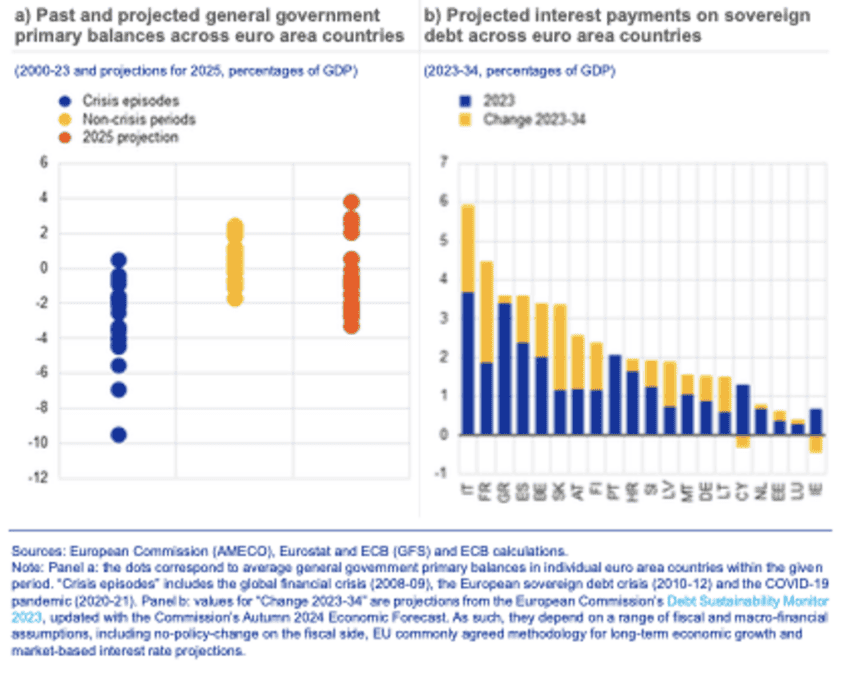

In its Financial Stability Review form November last year, the ECB highlighted Eurozone risks that followed from weak economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic and remaining high primary fiscal deficits in many countries. Weakening economic weather conditions because of Trump’s tariffs will surely impact on the fiscal balance in most EU countries: strong EU retaliation would amplify it. The ECB already pointed to how high debt costs for many governments remain a problem – and that they will lead to higher debt interests in the coming years as countries continue to roll over debt at higher rates than previously (see panel B in the chart below). In this scenario, Italy looks at debt costs close to 6 percent of GDP. France is lower at 4.5 percent of GDP. Still, these two economies are the second and third largest economies in the Euro Area, and policies that reduce economic activity and amplify uncertainty generate different effects in the membership because debt sustainability is different.

Chart 3: Persistent primary deficits raise risks related to high debt levels, especially as interest payments are set to raise further

3. There Is No Model for Retaliation

My third argument against trade retaliation now is that there is no real model of action or thinking for what retaliation is supposed to achieve – beyond the righteous feeling of frustration and anger with the Trump administration. I have spoken to a lot of people in the European Commission and member state governments that are investigating the scenario of retaliation: few have a clear idea of what actions could achieve better outcomes in US policy and avoid harming the EU economy. If Europe retaliates, and especially if it retaliates on par with the volumes affected by Trump’s tariffs, Europe’s economy will be injured. Retaliatory tariffs are no different from tariffs: while they reduce the export sector of targeted countries, they also injure the implementing country. Just as the US economy is the main casualty of Trump’s tariffs, the EU economy could be the main victim of retaliation (see also section 4).

There are two standard arguments for retaliation. First, a country retaliates to level mercantilist injury and create a basis for negotiation between the two parties about taking down the tariffs. It is a method to achieve a certain result. The second motivation is the demonstration effect: a country retaliates to communicate to aggressors (current or potential) that they cannot take hostile action with impunity. Absent a doctrine that would prevent any country from taking hostile tariff actions in the first place, retaliation is a way of protection against additional aggressions.

I have difficulties seeing the applicability of these motivations now. I rather think there is a great risk of escalation if the EU would go ahead with retaliation. For the EU to level mercantilist injury and create a basis for negotiation, it would have to introduce very substantial retaliation measures. The bigger the retaliation, the higher the injury to the EU’s own economy – and the more it would risk provoking additional hostilities (as per the US’s escalation with China).

Nor do I find it likely that the US administration would return to economic rationality, and thus respond to EU retaliation with a greater desire to cancel their initial aggression. Retaliatory decisions that have been taken by the EU don’t seem to have moved Trump and his folks in such a direction – both under the first and the second Trump administration. True, these retaliatory measures concerned more limited matters (the US tariffs on steel and aluminium), but it is notable that they had no effect on Trump.

I seem to share this view with many of those who are supportive of retaliation: they don’t think Trump will change his position as a result of EU retaliation and are observant of Trump’s stance that he is planning tariffs on other goods that would have effects on EU’s trade (especially pharmaceutical products). But it begs the question: if the expected result of tariff retaliation is no change to the original assault, why should the EU then retaliate and, in the process, injure its own economy?

If the US is not acting on the basis of economic rationality, it follows that US tariffs on the EU is unlikely to go away. The EU could achieve some results through negotiations on the “reciprocal” part of Trump’s initial tariffs. There may be some potential to achieve adjustments to the new US baseline tariff as well, but this is unlikely to be the result of proper trade negotiations in the next months. It may eventually happen by other means: purchasing agreements, a bigger deal on security and the economy, currency appreciations affecting EU exports, or something else. The point is: the most likely scenario now is that US tariffs against EU exports three months from now will be higher than they are today.

There is, of course, an important difference between the US and the EU. The US tariff package targets the exports of all its trading partners while EU retaliation would only impact on the exports of the US to the EU. Therefore, EU imports could be less affected by the reallocation of trade: it would import less from the US but more from others. As a result, the economic effects of the EU retaliatory tariffs would not necessarily be very bad. Now, this effect is partly dependent on the design of the retaliation, and this is a tricky part. The choice of retaliation should reduce US exports but be concentrated to product categories where it is possible to substitute trade with the US.

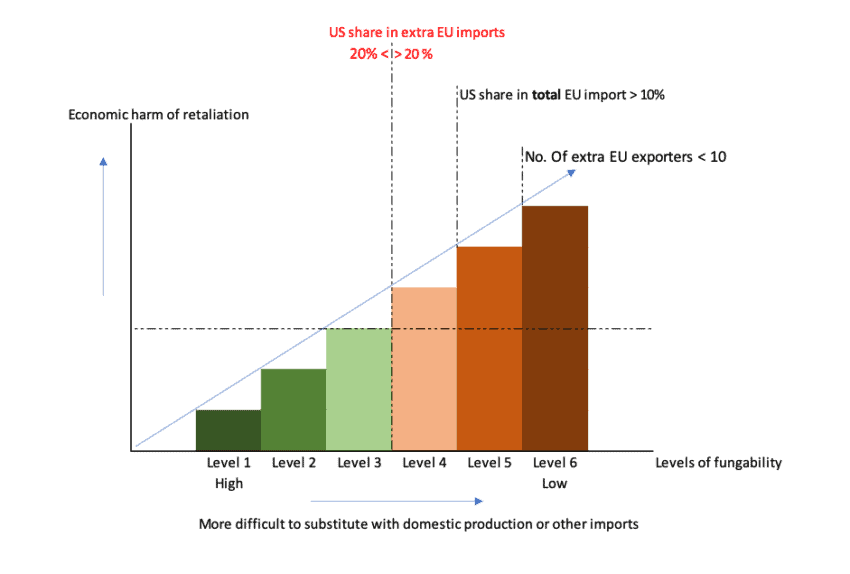

Is there a good way of achieving such an outcome? In short, it’s difficult. A few years ago I did a conference paper studying an EU list of retaliatory tariffs against the US, and found some interesting patterns. I created a simple model of trade fungibility that followed a step-approach for determining how easy it would be to substitute US imports that would be exposed to new and punitive-level tariffs (see chart below).

I used six levels of fungibility. I started with the following question: does the US share of extra-EU imports represent more or less than 20 percent of total extra-EU imports in the product category? If the US share was less than 20 percent of the total extra-EU imports, the product would be allocated to levels 1-3 (depending on a few other analytical steps) and generally be treated as fungible. If the US share was higher than 20 percent, the product would fall in categories 4-6. To level up to category 5, there was an additional threshold to pass: the US share in total EU imports (including intra-EU imports) had also to be higher than 10 percent. In such a scenario the opportunity for substitution would be additionally smaller. And to get to level 6, the product in question would have fewer than 10 extra-EU importers – meaning fewer trading partners that could compensate for the loss of imports from the US.

Chart 4: Levels of fungibility

When I calculated the trade effects (on EU imports of US goods) for these levels, I found that only 44 percent of the trade reduction would emerge in levels 1-3: the levels where fungibility is high. A higher share of the expected trade reduction with the US was represented by categories 4-6. And the level with the highest trade reduction was level 5 – a category where US imports was higher than 20 percent of all extra-EU imports and 10 percent of all EU imports (but where there are more than 10 extra-EU exporters). 47 percent of all trade reduction following the EU retaliatory tariff package was represented by this category. Certain products represented the bulk of the effects: aeroplanes, motorcycle parts, and chemicals. A tariff on these products would all have impacts on EU users.

The point is: it was difficult for the EU to sign a small retaliation package against the US without including products with low fungibility. Obviously, it is going to be a far harder task to design a very big retaliation package (on par with the baseline US tariff plus any reciprocal top-up tariffs) without injuring EU importers by including products that is difficult to substitute in a short period of time. EU goods imports from the US is deep and wide: it includes thousands of different products and represent a varying degree of saturated production structures. Over time, of course, the EU economy will also absorb the effects of big EU retaliation but it is going to take years for that to happen.

Reasonable people can disagree on the question of the economic effects of retaliation. It is ultimately a question about interpretation and judgement. What concerns me is that those supporting trade retaliation have no real model for what they think retaliation will achieve and how they will impact on the EU economy. I think such a model is needed. Without one, and with rash decision making also in Europe, there are greater risks of economic injuries and setting in motion a sequence of events which is very undesirable.

4. The “Big Bazooka”: What Are You Firing Against?

The rational for including services and intellectual property flows – plus other non-traditional instruments – seem to come in three versions. First, the EU has a big trade surplus in trade in goods with the United States, and to achieve some form of parity with the US tariff assault the EU needs to include other sectors and other flows than goods and those that can be subject to a standard tariff. Second, it is believed that actions on US services especially would impose greater economic harm on the US economy. And third, changes in the EU trade defence armoury – especially the introduction of the Anti-coercion Instrument – have opened for new forms of retaliatory trade actions: the EU, in some law of motion, should therefore use these new opportunities.

Supporters of using the Anti-coercion Instrument often use a combative language. The EU, they suggest, should use the “big bazooka”. It is an indicative choice of words – and it is also apt. Subjecting services or intellectual property flows to retaliatory measures is, in the first place, an escalation. It is tantamount to opening a new front in a war. And the purpose of using a bazooka is to effect greater destruction. If you have fired a bazooka, you can’t unfire it. Retaliatory tariffs are different in the sense that they are an ad valorem cost on imports: the logic behind them is that, if they are finally taken away, trade opportunities will return. The bazooka aims to destroy the imports: there is less, if anything, to return to.

I think there is, generally, an exaggerated belief in what actually can be done under the Anti-coercion Instrument: it’s structure and design do not generally fit with an approach where you seek a vast amount of trade retaliation. My substantive concern is rather about knowing – or, more precisely, not knowing – what you are harming when a restriction is imposed on certain flows of cross-border exchange. The imports of services from the US cover many different types of sectors and types of flows, and some of them are boilerplate and areas you don’t want to expose to restrictions: tourism, for example. It is known that imports of services are also tied to trade in goods, and as goods trade decline because of Trump’s tariffs (and potential EU retaliation on tariffs) there will be depressing effects on trade in services too. Likewise, there are spontaneous and “non-government” forms of “retaliation”. For instance, European travel to the US has declined substantially because of Trump administration policies, leading to a decline in US services exports to the EU.

But a more important reservation is that the import of services is closely tied to value-added generation in the recipient economy. It is well established that the value-added in service exports is high and that the “servicification” of manufacturing has increased value-added in trade in goods. But it is also the case that many services that are imported have a strong and significant impact on local value added. This effect differs a bit depending on the type of services imports – e.g., low-value added services outsourcing have somewhat different import effects than high value-added imports from other advanced economies – but it is most likely stronger for EU imports of services from the US than from many other countries.

Given the nature of services, many business and professional services, financial services, and ICT services combine imports and local value added. A management service by, say, McKinsey or BCG delivered to an EU customer will include local staff and resources in the EU plus non-EU countries (including the US). It is difficult to measure levels of local value added and services imports, but there is strong intimacy between the two. In other words, the imports of services have a positive effect on local value-added: the more you import, the more value-added tend to be generated.

Moreover, some imports of financial services supports US investment in the EU. Good amounts of the imports of ICT services take place to complement local-valued in ICT services and improve what can be offered or delivered to a local European customer. For instance, the EU import of Netflix services from the US have a material effect on what Netflix can produce and stream in the EU. Disentangling value-added in services trade and in local production is, in the first place, very hard to do. The risk is for those who want to hit services in a retaliation package is that the EU will not hit import flows as much as local value-added.

Similarly, intellectual property flows (e.g., royalties) may sound as a simple flow to target for restrictions. They aren’t. A first caution should come from the sheer fact that an import of intellectual property is often an import of the right to use applied knowledge: restricting this import or exposing it to a higher cost may mean that EU importers will use less of it. Royalties, for instance, are paid by EU firms that produces pharmaceutical products that are protected by patents held by US firms. What’s more, a critical aspect of these flows is connected to corporate income tax and tax agreements. This is an extraordinarily complex area, as many past initiatives to agree on models for corporate income tax distribution has shown. It gets even more complex if the intellectual property flow is tied to modern service production. The logic behind a retaliatory action would be to reduce the royalty flow from the EU to the United States. But is that in Europe’s economic interest? I doubt it is. In the first place, these flows partly allow for more corporate income by US-based companies to be taxed in the EU: they are a necessary input for how US multinationals structure tax residencies and localise their income. A tax on the intellectual property flow, if it is substantial, would be followed by necessary adjustments in the localisation of income – and some of these adjustments would have the effect of reducing the corporate income tax base in EU countries.

It all boils down to a basic question: if the EU includes services and intellectual property flows in a retaliation, can it be sure that it won’t produce serious harm on European economic interests? My answer is a clear no. This field is more characterised by “known unknowns” than by the “known knowns” – the things we know we know. It is also infused with “unknown knowns”, if I can add a category to Donald Rumsfeld’s epistemological taxonomy. We know, for instance, that EU services imports from the US in advanced services production is substantial, but we don’t know exactly how the business processes work and the extent to which there is substitution opportunities. Before we have better knowledge of such an important feature of the European economy, the EU should avoid exposing them to new trade restrictions.