Published

The Next Stages of UK Trade Policy

By: David Henig

Subjects: UK Project

The context for UK trade policy in the future remains unclear. It is possible but unlikely that the UK will be leaving the EU with full future control at the end of March, but more likely that it will be leaving after a delay, in a transition period with limited control and an uncertain date on which further control can be taken.

The first set of UK Trade Policy decisions to support both scenarios have been made, though not all have at the time of writing been published. The depth of commitment to these decisions has yet to be proved, and there is also little evidence that they have been robustly tested, particularly the extent to which there are conflicts between them.

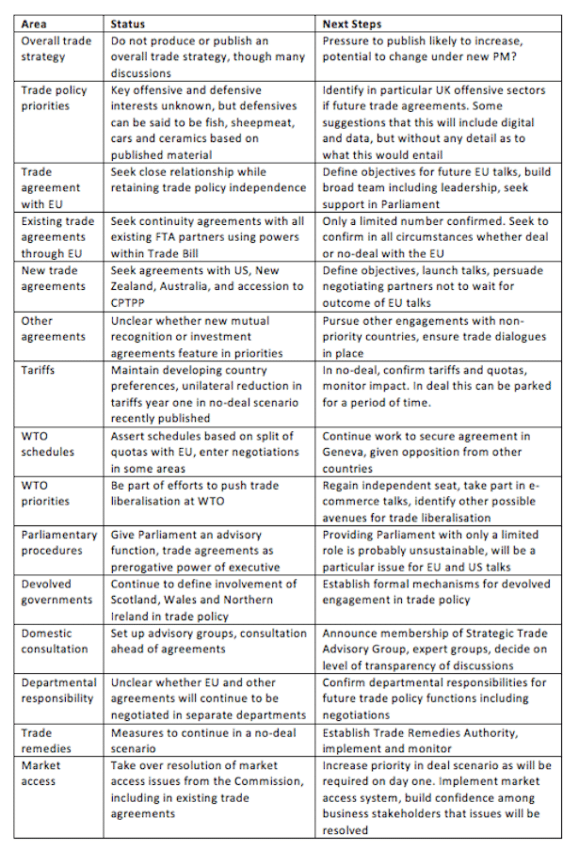

To summarise the UK’s current trade policy picture:

This is a daunting work plan particularly in a no-deal Brexit, but even in the scenario of deal and future negotiations. There are four particularly areas of conflict we envisage:

- New Free Trade Agreements against continuity agreements: The programme of ensuring the UK will still be covered by EU trade agreements after Brexit has not gone as well as hoped, with few agreements in place for no-deal Brexit, and uncertainty about whether all will continue in the case of a deal. What this means is that under either scenario new agreements with the likes of Australia and New Zealand will be competing with continuity agreements with Japan, Turkey and others;

- EU against US trade agreements: There are known differences between EU and US approaches in areas such as Geographical Indications, voluntary standards, and most of all food safety regulations. The UK is going to have to make a choice at some point which may put one of these agreements in jeopardy. There is already a growing public campaign against a US trade deal;

- Parliament, devolved, and stakeholder engagement: MPs, devolved assemblies, and stakeholder groups are all unhappy with the current level of engagement, and plans for the future. In particular the proposals for consulting with Parliament and devolved assemblies are considered inadequate by large numbers of politicians, and this is likely to become an issue particularly with the big negotiations, with the EU and US. Until there are new proposals we can expect continuing frictions;

- Departmental frictions: It has often been commented that the EU Member States have been surprisingly united in Brexit talks to date, but if tensions emerge between them when thinking about future relations the same is likely to be the case for UK Departments. There are already tensions between the Department of International Trade and others including those departments representing agriculture and business. Managing these tensions in the next stage will be tricky.

Initial expectations of what the UK could achieve with an independent trade policy were high, but recent news on the limited number of trade agreements agreed in a no-deal scenario, and controversy over the initial tariff announcement, have led to a degree of greater realism. In both cases the criticism was as much about the initial secrecy as the actual content, and the main lesson the UK Government still have to learn in trade policy is to be more open with Parliament and other stakeholders.

Inevitably there will be teething troubles as UK Trade Policy moves into a new phase, particularly we expect in terms of progressing market access issues. Some of this has also been previewed by the extensive discussions over the impact of a no-deal Brexit. We think that UK stakeholders are ready for serious discussions with the Government about future direction, so potentially we could move on from this initial phase to one with deeper and more open engagement.

The alternative, of continued friction between Parliament and stakeholders on one side, and Government on the other, would slow the UK’s progress. It may turn out that a long extension is granted by the EU for the UK to renegotiate Brexit. In this situation it would be good to have the serious debate that hasn’t quite yet happened on trade policy and strategy. In other scenarios the UK will face more immediate challenges, in which case the best solution would be to move as quickly as possible to a ‘one-UK- team approach.