Published

South Korea Versus Japan: What Can the EU Learn From the Two Countries?

By: Andrea Dugo

Subjects: South Asia & Oceania

When discussing the issue of Europe’s waning competitiveness, analysts are almost instinctively driven to turn to the US for solutions. Draghi’s report on the future of European competitiveness, for instance, references the US some 612 times in under 400 pages. We at ECIPE have also often drawn parallels between the EU and the US, and not without reason. Over the past three decades, in fact, the US has experienced gains in productivity and economic growth unlike any other advanced country. Nearly all US states – 48 out of 50 – now enjoy higher levels of economic prosperity than the EU. Moreover, while European countries face stagnation in R&D spending and lag behind in technological advancements, US tech innovation is thriving like never before. It is only understandable that European experts and policymakers often look to the US for insights on what it has been doing right.

However, focusing exclusively on the US risks becoming limiting. The comparison, it is said, makes logical sense as the two blocs are broadly similar in terms of size, population, economic prowess and culture. Nevertheless, fixating on the US alone inevitably restricts the range of policy solutions available to the EU, and worse, cements the idea that there is some sort of American exceptionalism in maintaining competitiveness in today’s global economy – a misconception that does not hold up under closer scrutiny. While discontent with current capitalist systems is certainly widespread, particularly as major economies in Europe and Asia stagnate, there are other countries – from Switzerland to Taiwan – that have managed to navigate the turbulent waters of the current global economic order rather successfully. One nation that deserves special attention in this context is South Korea.

Since the early 1990s – during the same thirty years that have seen Europe decline across virtually all metrics of economic and social prosperity – South Korea has achieved what can only be described as an economic miracle. Following in the footsteps of other Asian economies like Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, South Korea also embarked on a path of rapid industrialisation and growth starting in the 1970s. Development came but took longer than elsewhere. By the early 1980s, life expectancy stood at just 65 years across the entire Korean peninsula, both north and south of the 38th parallel. Even as late as 1988, at the time of the Seoul Olympic Games, North and South Korea remained more similar than different. That same year, 1988, however, marked a pivotal turning point in South Korea’s recent history. In the months leading up to the Seoul Summer Olympics, massive worker and student protests had brought an end to South Korea’s dictatorship and ushered in democratic reforms. These changes accelerated the country’s already ongoing export-led industrialisation and set the stage for its full-scale economic take-off.

From an economic – as well as political – perspective, South Korea today is virtually unrecognisable from then. When compared with Europe, in the late 1980s, the Asian country enjoyed a level of economic prosperity far below any Western country and barely above that of a handful of stricken Eastern European countries emerging from the collapsing Soviet Union. Thirty years later, South Korea’s GDP per capita now exceeds the EU average, and has even outstripped mature economies like Italy or Spain. As the country is poised to overcome its hereditary regional foe and neighbour – Japan – in terms of per capita GDP for the first time this year, a more in-depth analysis is called for to understand the dynamics behind South Korea’s transformation, and perhaps learn lessons from what looks like more than a conventional narrative of economic modernisation.

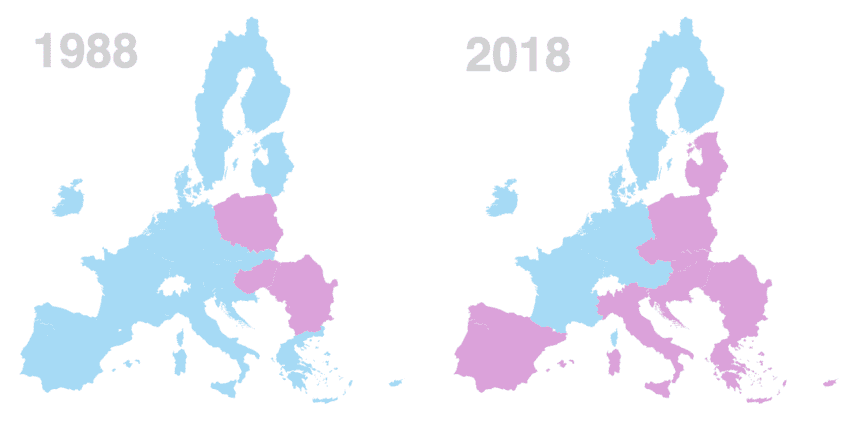

Figure 1: Comparison of South Korea’s GDP per capita with EU-27 Member States, 1988 and 2018 (constant 2011 prices; Blue = higher than South Korea, Pink = lower)

Source: Maddison Project Database.

Source: Maddison Project Database.

For a long time, to ensure it would replicate its economic success, South Korea almost slavishly emulated Japan’s development story, focusing on export-driven modernisation through substantial government subsidies. With significant international aid, particularly from the US, flowing into Seoul after the Korean War, the government strategically allocated special loans and financial assistance to chaebols – large family-owned conglomerates instrumental in revitalising key industries like construction, oil, and others. With their roots stretching back to the Japanese colonial era, chaebols were the Korean counterpart to the Japanese pre-war zaibatsu and post-war keiretsu, vast industrial and financial conglomerates characterised by their close ties to both the government and banking systems. By the late 1970s, the government’s approach extended to promoting initially unprofitable sectors such as steel, heavy industries, and chemicals, eventually branching into automotive and electronics manufacturing. This shift laid the foundation for South Korea’s rapid transformation into an industrial powerhouse, with chaebols such as Samsung, Hyundai and LG playing a pivotal role in the nation’s rise as a global economic leader.

For South Korean policymakers, following Japan’s trail of economic development seemed the only reasonable thing to do. Japan had emerged from the rubble of World War II to become an economic juggernaut capable of rivalling the US global dominance in a matter of decades. In 1960, Japan’s GDP was only 8% of the US’s; by 1995, with less than half the US population, it had risen to 71%. Japan’s economic boom even extended to the land under its feet. At the height of a decade-long property frenzy in the late 1980s, the 3.4 square kilometres encompassing Tokyo’s Imperial Palace were famously valued higher than the entire real estate market of California. The boom also spilled over into the financial sector: between 1980 and 1988, Japan’s share of the world stock markets soared from 15% to 44%, while the US share fell from 53% to 31%. In 1989, out of the world’s top 20 companies by market cap, 13 were Japanese. Japan was viewed as the polar star of economic development, and South Korea, naturally, sought to follow suit.

The 1990s, however, saw the burst of Japan’s economic and property bubble, plunging the country in the doldrums. What began as the infamous “Lost Decade” gradually stretched into the “Lost 30 years,” as Japan struggled to escape a cycle of slow or negative economic growth that persists to this day. In nominal terms, Japan’s GDP dropped from $5.55 trillion to $4.21 trillion between 1995 and 2023 – a 24% decrease. Over the same period, the US economy grew by 358%, China’s by an astounding 1851%. Japan’s influence in global markets has also withered: its stock market now accounts for just over 5% of the worldwide share, and only one Japanese company ranks among the top 100 globally by market capitalisation – Toyota. For reference, South Korea also has one company in the top 100 – Samsung – which consistently ranks higher than Toyota. The bigger they are, the harder they fall, as the saying goes. As South Korea entered the 1990s with a dynamic and rapidly expanding economy, Japan served as both a powerful example of past economic success and a stark warning of how quickly fortunes can reverse. To the casual observer, the two nations might appear perilously alike, yet South Korean policymakers have been deliberate in steering the country away from following a carbon copy of Japan’s trajectory.

South Korea and Japan undeniably bear strong resemblance. Beyond their geographic proximity and deep historical and cultural ties, the two countries share matching social and economic structures, and are confronted with similar challenges. Both South Korea and Japan boast among the world’s highest life expectancies but are also grappling with some of the lowest fertility rates and fastest-aging populations, leading to mounting pressure on their social welfare systems and labour markets. As mentioned before, both countries have built their modern success on export-driven growth, with strong manufacturing bases that have produced globally dominant industries in electronics and automotive. Both South Korea and Japan still rely heavily on those large conglomerates that have played pivotal roles in shaping their economies, and this corporate dominance has also contributed to similar structural challenges, such as wage stagnation and a rigid job market. Lastly, despite their advanced economies, both nations are characterised by relatively low productivity levels compared to other developed countries.

Nevertheless, the similarities between South Korea and Japan should not overshadow the differences between the two countries, particularly in the policy innovations and development strategies South Korea has adopted since the mid-1980s to progressively unravel from Japan and establish its own competitive economic framework. Three main sets of factors set South Korea apart from Japan’s earlier model: R&D spending and innovation, trade openness and human capital investment.

Since the mid-1980s, and much more markedly from the 1990s onwards, South Korea strategically shifted away from its Japan-centred development model in a bid to modernise and diversify its economy. For decades, Japan had been South Korea’s primary trading partner, foreign investor and provider of capital and technology. However, as South Korea aimed to build an independent technological and production base, Japanese companies became increasingly hesitant to share core technologies, driven largely by fears of South Korea’s rapid catch-up in industrial and technological sectors. This reluctance prompted the South Korean government and firms to actively seek alternative sources of trade and technology, mainly turning to Western countries.

By the 1990s, the US replaced Japan as South Korea’s primary source of investment and technology, especially in capital- and technology-intensive industries like electronics and IT. In this context, South Korea took a fundamentally different approach in the development of its industries, primarily the information technology one. While Japan prioritised developing proprietary technologies, which had limited international compatibility, and imposed protectionist regulations to shield domestic companies, South Korea embraced competition and collaboration with Western nations. South Korean firms formed strategic alliances with US and European companies to access advanced technology, positioning them to compete on a global scale. The South Korean government also adopted a more liberal approach, encouraging competition by allowing new entrants into key market segments ahead of incumbents. This competitive and open-market strategy helped South Korea rapidly grow its IT industry and propelled technological innovation in these sectors.

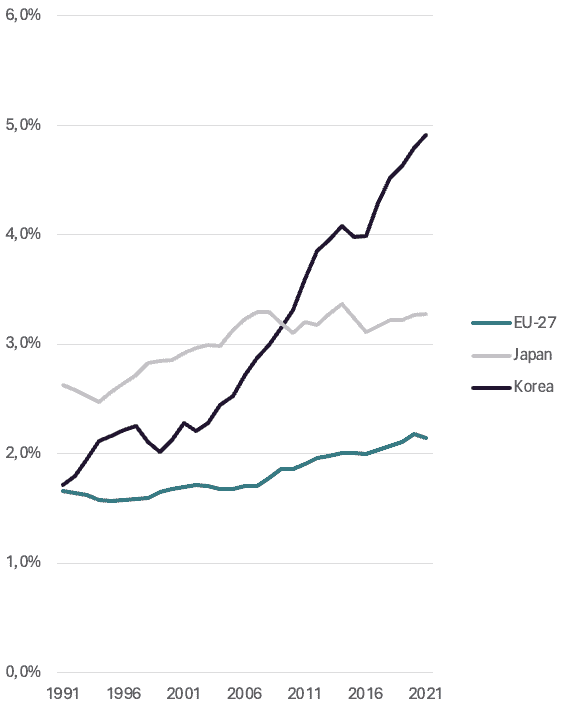

The evolution of R&D spending in South Korea and Japan mirrors these two opposite strategies on innovation. As Figure 2 shows, in 1991, South Korea spent 1.7% of its GDP on R&D, roughly on par with the EU. In contrast, Japan devoted 2.6% of its GDP to R&D expenditure – 53% more than South Korea in relative terms. Over the past thirty years, however, R&D intensity in South Korea has experienced an almost threefold increase to reach 4.9% as a share of GDP, the second largest percentage globally after Israel. Japan, on the contrary, has witnessed a much more contained surge in R&D spending, achieving 3.3% of GDP in 2021.

Even more interestingly, although private sector contributions dominate R&D spending in both South Korea and Japan – accounting for about 79% in the two countries, compared to just 66% in the EU – the industrial distribution of business R&D expenditure is strikingly different. As Figure 3 illustrates, Japan and the EU display a virtually indistinguishable breakdown, with R&D concentrated in a diverse range of industries but heavily dominated by the automotive sector. Research shows that innovations in this sector often find limited applicability beyond the transportation industry. In contrast, over 60% of South Korea’s private R&D spending is concentrated in ICT producing companies, whose technologies are widely applicable across multiple industries. South Korea not only surpasses Japan and the EU in terms of R&D investment but also demonstrates a stronger capacity to foster innovation with broader economic impacts. This positions South Korea more favourably to leverage technological advancements in the modern global economy.

Figure 2: Gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD) for South Korea, Japan and the EU-27, 1991–2021 (percentage of GDP)

Source: OECD.

Figure 3: Business R&D spending distribution by industrial sector for South Korea, Japan and the EU-27, 2022 (percentage of total)

Source: 2023 EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard.

Keeping the focus on the private sector, however, it is important to note that the big influence of chaebols remains a significant issue in the South Korean economy. Although policymakers have come to recognise that relying exclusively on large conglomerates is insufficient for sustaining economic growth, and have accordingly shifted their efforts towards promoting domestic SMEs and startups as the key drivers of innovation and competitiveness, the economic weight of chaebols is still substantial. For reference, the combined revenues of the five largest South Korean conglomerates – Samsung, Hyundai, SK, LG, and Lotte – make up approximately 45% of the country’s GDP. The encouraging news is that this share has decreased dramatically – it was 70% in 2012 – and, more importantly, that the government has been actively implementing measures to diversify growth and nurture a more dynamic entrepreneurial ecosystem. Some of these initiatives include the launch of a $3 billion venture capital fund for startups in 2019, further reinforced in 2023 by the Ministry of Science and ICT’s announcement to invest $12 billion by 2027 to help create ten deep-tech unicorns – tech startups to be valued at over $1 billion.

These policies appear to be yielding results. According to the Global Innovation Index 2024, published annually by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), South Korea ranks 6th globally, trailing only Switzerland, Sweden, the US, Singapore, and the UK, while surpassing countries like Finland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark. In contrast, Japan holds 13th place in the same ranking. WIPO Director General Daren Tang has attributed South Korea’s impressive performance to its innovation-focused regulations and significant private sector investment in R&D. Similarly, the Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2024 ranks Seoul 9th among 300 global startup ecosystems, a significant leap from 2019 when it did not even make it to the top 20. Seoul now outpaces Tokyo, which ranks 10th, and all ecosystems in the EU. Moreover, as of July 2024, South Korea boasts 15 unicorns collectively valued at nearly $35 billions, while Japan lags behind with just 8 unicorns, valued under $11 billion – less than a third of South Korea’s total valuation.

South Korea is undeniably pulling ahead in the global innovation race, not only outpacing Japan but also surpassing many advanced European economies. Not unlike Europe with its “national champions” narrative, Japan is also a prisoner of its own past, stubbornly intent on preserving the corporate behemoths that once cemented its global economic leadership. Japan’s banking system, notoriously reluctant to lend to startups and SMEs due to the Basel capital requirements, further exacerbates the issue.

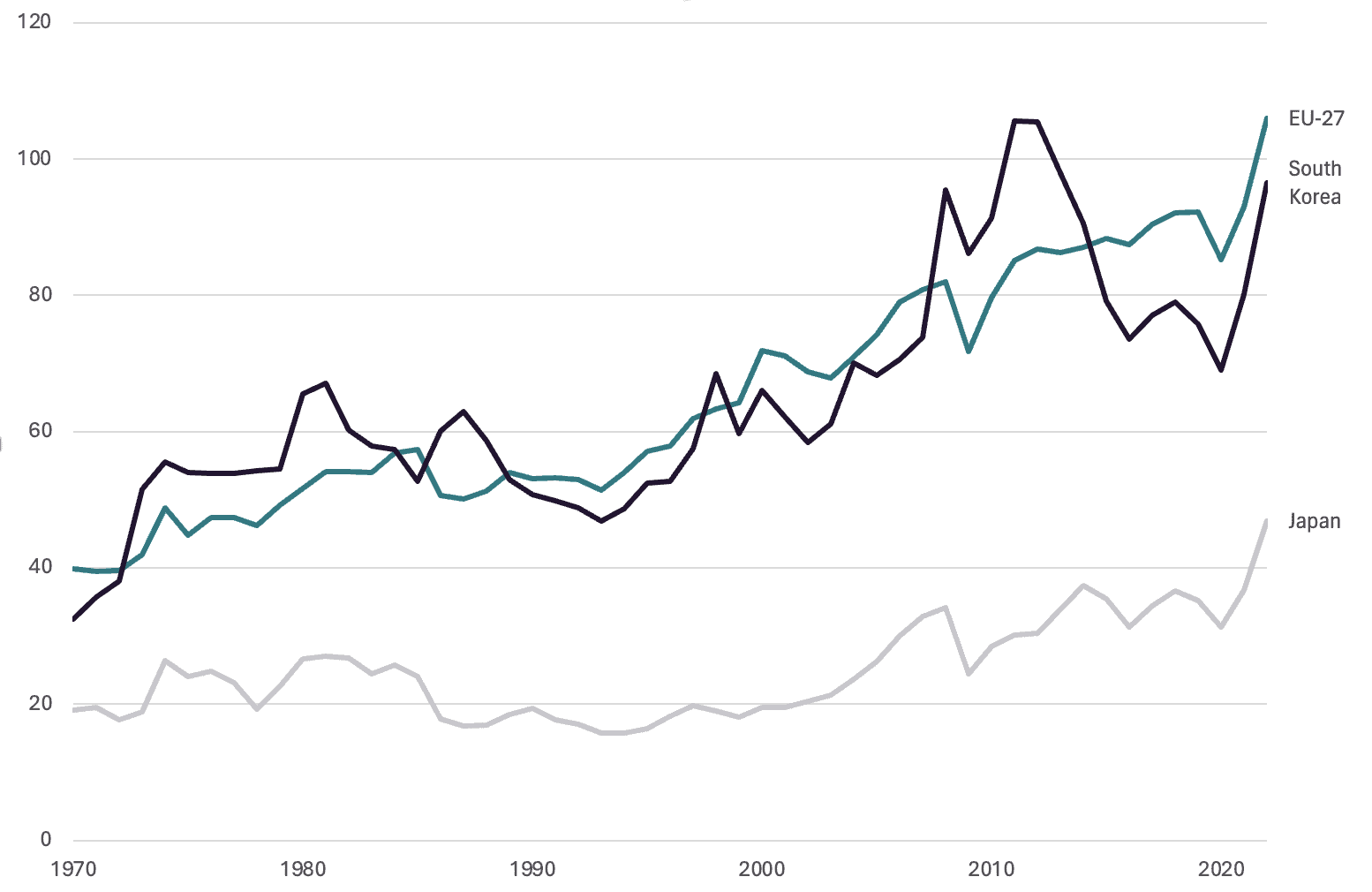

Another prominent point of divergence between South Korea and Japan is their respective approaches to trade openness. Although both nations have relied on exports to drive industrialisation, the extent to which trade weighs on their economies is vastly different, and has been increasingly so with the passage of time. As depicted in Figure 4, which shows imports and exports as a share of GDP for South Korea, Japan, and the EU (for reference) since 1970, trade has consistently played a more crucial role in South Korea’s economy than in Japan’s.

This gap can be partially attributed to the fact that smaller nations, such as South Korea, tend to be more trade-dependent than larger countries, as they rely more on imports to satisfy domestic demand. However, the disparity between the two countries has grown over time, accelerating from the 1990s onwards. Today, trade accounts for nearly 100% of South Korea’s GDP, a figure comparable to that of the EU. In contrast, trade makes up less than 50% of Japan’s GDP, aligning it more closely with much larger economies like the US and China. This widening chasm highlights South Korea’s increasing reliance on international trade and its broader integration into the global market, while Japan has maintained a relatively more insulated economic structure.

Figure 4: “Trade openness index” for South Korea, Japan and the EU-27, 1970–2022 (sum of exports and imports of goods and services divided by GDP, percentage)

Source: Our World in Data.

The impact of trade openness on South Korea’s economic growth and competitiveness over the past few decades has been profound. An Asian Development Bank study highlights that during the 2000-2010 period, for instance, trade openness accounted for approximately 0.2 of the 1.4 percentage points average annual growth differential between South Korea and the US. South Korea’s trade-driven growth model has been crucial to its sustained economic development and transformation into a technologically advanced economy. International trade has provided South Korean industries with access to vast external markets, facilitating the country’s rapid technological adoption and innovation. This global exposure not only boosted demand for South Korean products but also accelerated technological learning, enabling domestic industries to enhance productivity and move up the value chain, particularly in manufacturing sectors like electronics, automotive, and machinery. Unlike Japan’s more protectionist approach to trade, South Korea’s strategy underpins the importance of global trade in maintaining competitiveness and driving continuous growth.

Lastly, South Korea has outpaced Japan in human capital investment over the past few decades. While both nations fare extremely well in terms of leveraging the economic and professional potential of their citizens – the World Bank consistently places South Korea and Japan among the top five globally in its annually released Human Capital Index – South Korea appears to have been more successful in translating this very potential into tangible economic growth.

If we take the education dimension to human capital, for instance, South Korea has achieved one of the most impressive metamorphoses in recent history. In 1995, only 18% of the population aged 25-64 had attained higher education, a figure significantly lower than most advanced economies. By 2022, through comprehensive government investment and reform, that share had surged to 53%, the fourth highest among OECD countries – Japan ranks second. However, South Korea’s educational success is even more remarkable than this. Whilst considerably high, the overall level of adult educational attainment is influenced by the fact that South Korea modernised later than North America, Europe or Japan, hence making its older cohorts comparatively less educated than other developed economies. Today, however, South Korea leads the world in higher education enrolment, with nearly 70% of its 25-34 year-olds holding a university degree – Japan follows in third place with 66%, while Ireland is the first EU country, ranking fourth with 63%.

South Korea also excels in the quality of its education. South Korean students consistently rank among the top performers globally in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which assesses the academic achievements of 15-year-olds across OECD countries. Not only do South Korean students display high academic achievement, but the link between their socio-economic backgrounds and their test results is rather weak, suggesting that the country has managed to establish a relatively equitable education system as well.

The combination of South Korea’s advancements in both the level and quality of education has transformed an otherwise poorly educated workforce – in 1980, over 50% of all workers had barely completed primary education or less, nowadays, the majority holds college degrees – into one of the most skilled and adaptable to rapidly changing technology and entrepreneurial challenges. The rise in educational attainment among younger cohorts has played a central role in driving South Korea’s economic growth in recent decades, and is expected to yield even greater economic benefits in the coming years.

Estimates indicate that over the last thirty years, South Korea’s human capital has increased steadily at an annual rate of around 1%, contributing about 0.5 percentage points to yearly GDP growth. As educational levels continue to rise, human capital is projected to remain a key driver of future economic expansion over the next two decades. Moreover, South Korea’s leadership in other areas of human capital – the country had the highest number of researchers per million inhabitants globally in 2021 – will likely reinforce its continued success in innovation and growth, further solidifying its global competitiveness.

In addition to the three main trends already discussed – R&D spending and innovation, trade openness, and human capital investment – other tangent factors are likely to steer South Korea and Japan on diverging paths in terms of competitiveness. One such factor is the position of their public sector balance sheets. While Japan’s public debt is more than twice and a half the size of its GDP, South Korea can boast a government debt-to-GDP ratio at 54%, lower than some of Europe’s most ardent frugals like Austria, Finland or Germany. This more favourable position provides South Korea with considerable fiscal space, allowing the government to implement growth-boosting policies and better cushion the short-term negative effects of necessary structural reforms.

Another issue is the approach towards immigration. While both countries are highly culturally and ethnically homogenous, and have historically been cautious about immigration, South Korea appears to be embracing the presence of immigrants, driven by the recognition that it is a necessary measure in response to the country’s demographic challenges. Since the early 1990s, the number of foreign residents in South Korea has increased by some 40 times, from fewer than 50.000 to more than two million today. In comparison, Japan’s foreign-born population has grown from 850.000 to just under three million in the same period. As a percentage of the total population, immigrants now make up almost 4% of South Korea’s population, compared to just over 2% in Japan.

Although the difference may seem modest, it is projected to grow even wider. To address labour shortages, South Korea has significantly increased its foreign worker quota, from 70.000 in 2022 to 165.000 in 2024, nearly equalling Japan’s intake of technical trainees, despite South Korea having less than half Japan’s population. This shift signals a departure from South Korea’s historically temporary labour model, as the country moves towards a more sustained reliance on foreign workers. Furthermore, migrant workers in South Korea tend to enjoy higher wages than in Japan, making the country a more attractive destination.

A final factor worth considering is the potential for Korean reunification. While the prospect of a unified Korean Peninsula may seem as unlikely today as the revival of the Roman Empire, it remains a long-term possibility. A unified Korea would be as big as the UK, and almost as populous as Germany. While such an event would undoubtedly bring immense challenges – particularly in terms of social coexistence, and reconciliation of two vastly different economic and political systems – some studies suggest that a South-led reunification of the Korean Peninsula, if properly managed, could propel Korea’s economy to surpass that of all G7 countries, with the exception of the US.

In conclusion, South Korea is by no means the land of milk and honey. Demographic challenges are arguably more acute than those in virtually all EU countries, possibly even worse than Japan’s. Productivity growth has been sluggish, and the economy remains heavily dominated by powerful chaebols. However, over the past three decades, South Korea has displayed a feature that Japan once excelled in but has since lost, and one that Europe is in desperate need of: the capacity to reform. South Korea has demonstrated a unique ability to implement gradual structural reforms that make the country more open and competitive, addressing its problems without resorting to the simplistic solution of throwing more money at them. This is a rare quality these days.

Following the moment when the Americans forced Japan to open its ports to international trade in the 1850s, the nation rapidly elaborated a pragmatic doctrine that can be roughly translated to “Japanese spirit, Western technology.” In order not to succumb to the forces of Western imperialism and thrive in the new world of capitalism while preserving its cultural values and traditions, Japan became the first Asian country to embrace Western technology and economic thinking. While Japan’s economy has lost its previous agility, South Korea appears to have deepened its pursuit of economic progress and innovation. With a strong focus on R&D, South Korea accepts that productivity gains take time to materialise, and remains committed to long-term development. This stands in contrast with many EU countries, which struggle with productivity growth but fail to take the R&D challenge seriously, preferring to rely on government spending and debt to hide their issues.

Beyond offering policy lessons – such as a focus on innovation and human capital investment as well as an unwavering belief in the benefits of international trade – what Europe can really turn to South Korea for is its dynamic, adaptive approach to economic challenges. South Korea operates with the understanding that meaningful reforms require time to yield results, and remains steadfast in the pursuit of sustainable, long-term progress. What remains to be seen is whether Europe will follow South Korea’s path of reform, or Japan’s path of stagnation.

Very interesting – I have one question – my impression is that inward investment, especially in the form of acquisitions of Korean firms, has played a relatively small role in South Korea. Was there a deliberate policy to preserve nationally owned companies in important industries? I ask this partly because U.K. governments have often been criticised for relying too heavily on foreign acquisitions,.

Geoffrey Owen