Published

IP in EU Agriculture: Geographical Indications

By: Guest Author

Subjects: Agriculture Trade and IP

By Dr. Christian Häberli, World Trade Institute

Products with Geographical Indications (GI) are a common feature of everyday life, from Parma hams to Georgian wine appellations, Swiss Gruyère, Mexican Tequila, and French Cognac. GIs are a specific IP right that provides producers with the exclusive right to use the indication and to prevent its use by a third party whose product does not conform to the applicable standards or is not produced within the same region. A protected GI does not enable the holder to prevent someone from making a product using the same production methods as those set out in the standards for that indication. Moreover, all producers in the same region and with the same production standard have the right to use the protected name. Many, though not all, GIs are related to the agricultural and food industry. The main trade issue here arises when a protected name in one country is considered generic, for instance, by a competitor in a FTA partner country (“Emmental” or “Parmesan” cheeses).

GIs in EU Trade Policy today

GIs today figure most prominently in FTAs of the EU, but also in national regulations and FTAs concluded in other ‘old’ parts of the world, such as Asia and Africa. On the other side, ‘new’ countries such as the US, Australia, and New Zealand, favour different IP systems such as patents, brands, licenses, and private and collective trademarks such as “Idaho Potatoes”. The EU needs to take into account the global and the particular level of IP protection when negotiating trade agreements.[1] Note that many IP regulations and treaties enshrine also non-trade and non-economic features. With the US,[2] New Zealand,[3] Australia,[4] and Canada[5], specific, reciprocal and sometimes elegant ad hoc solutions could be found in bilateral negotiations, namely for EU wines and spirits.

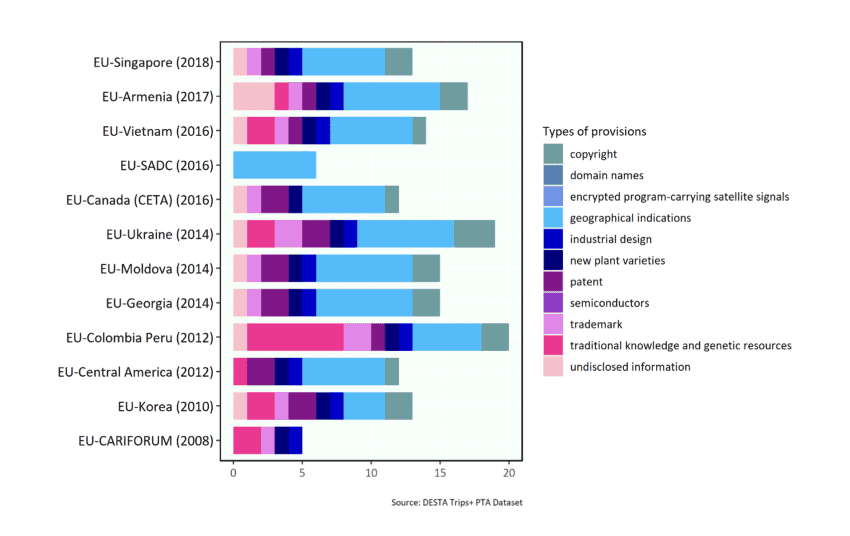

In the below DESTA overview of various EU FTAs, it becomes clear that GIs are the most prominent type of IP in EU FTAs from the EU-Korea FTA in 2010 onwards. For the EU-SADC (2016) FTA, GI provisions were even the only novel IP provisions. On average, EU FTAs contain 6 provisions on GIs per FTA.[6] This demonstrates the strong level of protection enjoyed by GIs, albeit only as a niche type of IP in monetary terms. Nevertheless, according to a former UK trade negotiator, “EU geographical indications are the number one ‘ask’ of the EU in all trade talks.”[7]

Figure 8.1: IP provisions in EU FTAs (including for GIs)

Potential and limits to further GI extensions

GIs in new EU FTAs are likely to involve countries without specific national GI regulations. Even though this is perfectly possible in the light of the sui generis nature of the IP protection framework under the WTO/TRIPS Agreement, this can be a daunting task for EU negotiators – even more so for a (potentially) high market value of such GIs and their competitors protected by other IP instruments.

The IP provisions in the CPTPP indicate the difficulties for protection of GIs à la EU in the “new world”, especially in respect of (collective or certification) trademark rights. Only GIs originating in the territory of a Party fall under these provisions. Nevertheless, registration, for instance of EU GIs in each CPTPP Party, is available according to national prescriptions and based on the TRIPS Agreement. TRIPS-Article 22.3 provides that “A Member shall, ex officio if its legislation so permits or at the request of an interested party, refuse or invalidate the registration of a trademark which contains or consists of a geographical indication with respect to goods not originating in the territory indicated, if use of the indication in the trademark for such goods in that Member is of such a nature as to mislead the public as to the true place of origin.” (emphasis added, demonstrating the negotiable character of a full protection for EU GIs)

This is not the place for a detailed examination of GIs in the “new world” or in their FTAs with the EU. What seems clear, however, is that negotiations could be extremely difficult when GI proponents like the EU27 (or the UK) try to secure GIs through an accession to the CPTPP, or with specific countries. However, thanks to the WTO/TRIPS Agreement and the non-contested right accruing to all WTO Members to protect their GIs, there is room for flexibilities and creative solutions.

Conclusions

One of the main objectives of EU agri-food trade policy is to promote regional specialty foods in the Common Market and internationally. For this purpose, the EU aims at protecting a specific type of IP, namely its geographical indications (GI), in multilateral and regional trade agreements. EU GIs come in four forms: (1) Protected Designations of Origin (PDO), (2) Protected Geographical Indications (PGI), (3) Geographical Indications of spirits, drinks and aromatised wines (GI), and (4) Traditional specialty guaranteed (TSG). Since the EU-Korea FTA, concluded in 2010, strong IP provisions are a common feature in all EU FTAs.

While FTAs do not ensure sales, there are strong economic reasons why GIs matter for the EU: 20% of total sales of GI protected food products are exported outside the EU – often sold at twice the price of similar products without GIs. In other words, even though production and marketing involves extensive, costly, and additional investment and marketing efforts from producers to processors and retailers, GIs can lead to higher sales premiums throughout the agri-food value chain. Moreover, many GIs protect traditional production methods and support agricultural sustainability. They also matter culturally: GIs protect traditional sectors in many regions in the EU, supporting regional culinary heritage, thus they encourage consumer trends towards “gastro-patriotism”. Registered GIs are disproportionately important in Southern EU Member States; political economy therefore demands that GIs are a key element for all EU FTA negotiations.

The break-down of the Doha Round negotiations, in 2008, where, inter alia, GIs for wines and spirits were to obtain additional protection under the TRIPS agreement in a multilateral register for these products already foreseen in Art.23.4, is not helpful for the further extension of GIs at a global level. Despite this lack of multilateral progress, governments increasingly establish and protect their GIs in trade agreements with other countries, along the EU concept or in mutual recognition agreements. Nonetheless, end-consumers alone can buy into the GI idea, believe in the quality of the production and processing monitoring, and then perhaps pay a price premium.

[1] On a global level, the Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement on Appellations of Origin and Geographical Indications adopted on 20 May 2015 improves the protection of GIs registered within the jurisdiction of each Contracting Party, enlarges the scope to all GIs, ensures full compatibility with the WTO/TRIPS Agreement, and allows the EU to be a contracting party on its own.

[2] The EU-US Wine Agreement commits the US to protect a list of “names of quality wines produced in specified regions and names of table wines with geographical indications”; on its side, the EU accepts to only use “names of viticultural significance listed in Annex V […] as names of origin for wine […] indicated by such name”. Cf. Agreement between the European Community and the United States of America on trade in wine, Official Journal of the European Union, L/872, dated 24 March 2006, Article 7 (“Names of origin”)

[3] Under New Zealand’s domestic law, only GIs for wines and spirits can be protected, since 2016 (GI Act). The GI Register lists all geographical indications registered in New Zealand – both New Zealand and foreign. However, until today New Zealand has no bilateral GI agreement with the EU. Cf. New Zealand Intellectual Property Office, accessed on 14 September 2021 at https://www.iponz.govt.nz/about-ip/geographical-indications/using-the-gi-register/

[4] The Agreement between Australia and the European Community on Trade in Wine, dated 1 December 2008, protects GIs for wines and spirits and lays down production and labelling standards. There is no bilateral agreement for other GIs.

[5] In the CETA, signed on 30 October 2016, the relationship between GIs and trademarks has been clarified for several EU names including Parma Ham, Black Forest Ham or Roquefort Cheese. They are now protected in their original language (but not as translations). However, CETA does not define this relationship more generally, and there are no conflict resolution principles for specific cases.

[6] DESTA (2020) [https://www.designoftradeagreements.org/ accessed 1 February 2021]

[7] Foster, P., and J. Brunsden, UK pushes back on Brexit promises on EU regional trademarks. Financial Times 2 April 2020.

We invite you to join the discussion on social media using #IPinEUFTAs and bookmarking our Trade and IP Project webpage to capture all future updates.

Please notice that TSGs are not GIs (neither are they any form of IPR).