Published

India’s Election and the Prospects for Growth Powered by Manufacturing Exports

By: Dyuti Pandya Vanika Sharma

Subjects: Far-East Regions South Asia & Oceania

India has often been touted as the world’s largest democracy. As more than 900 million people went to vote in April the Indian electorate has chosen the right-wing Bhartiya Janta Party (BJP) for a third consecutive five-year term. However, although the BJP government is the ruling party again, the status-quo of Indian governance has undergone two important changes.

First, unable to win a majority on its own, the BJP has had to form a coalition government in order to rule – the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). The NDA is a political alliance made up of close to 40 political parties. This number is subject to change as political parties are free to shift alliances, however parties such as Telugu Desam and Janata Dal United, which are more entrenched in regional politics rather than national, have been staunch allies of the BJP and the NDA. A coalition government such as the NDA is established when a single political party is unable to secure majority votes on its own. The results of the 2024 elections saw the BJP short by 32 constituencies leading to the NDA coalition to ensure its return to power.

Second and related to the first, the margins of the electoral conquest have been slim this year. This means that the opposing coalition – Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) – led by the Indian National Congress (INC) has secured more seats in the parliament, leading to a larger voice in political decision making and a stronger opposition. The new status-quo could lead to more friction in political decision making, but can also ensure more moderate and consensus driven regulatory reforms. This can have significant implications for India’s economic outlook – both domestically and internationally.

Modi 1.0 and Modi 2.0 – The beginning of the manufacturing era

In order to make assumptions about the future, it is first important to understand the past. The last ten years of PM Narendra Modi’s reign provide us with a clear view of Modi’s ambitions for India’s economic growth and an obsession with increasing India’s manufacturing prowess in a bid to displace China as a large global exporter of manufactured goods.

Under Modi 1.0 between 2014 and 2019, the primary objective was to accelerate India’s GDP growth, increase employment, eradicate poverty, and create wealth. By achieving these goals, Modi envisioned to drive India’s global influence. The crown jewel of Modi’s first term was the illustrious Make in India program devised to transform India into a global design and manufacturing hub through investment in infrastructure and investment promotion. However, in the first five years of the program, investment in the manufacturing sector declined from 23.1 percent to 21.8 percent of GDP between 2014 and 2019. India’s overall economic health also deteriorated massively between 2014 and 2019, with the GDP growth rate falling from 7.4 percent to 3.9 percent.

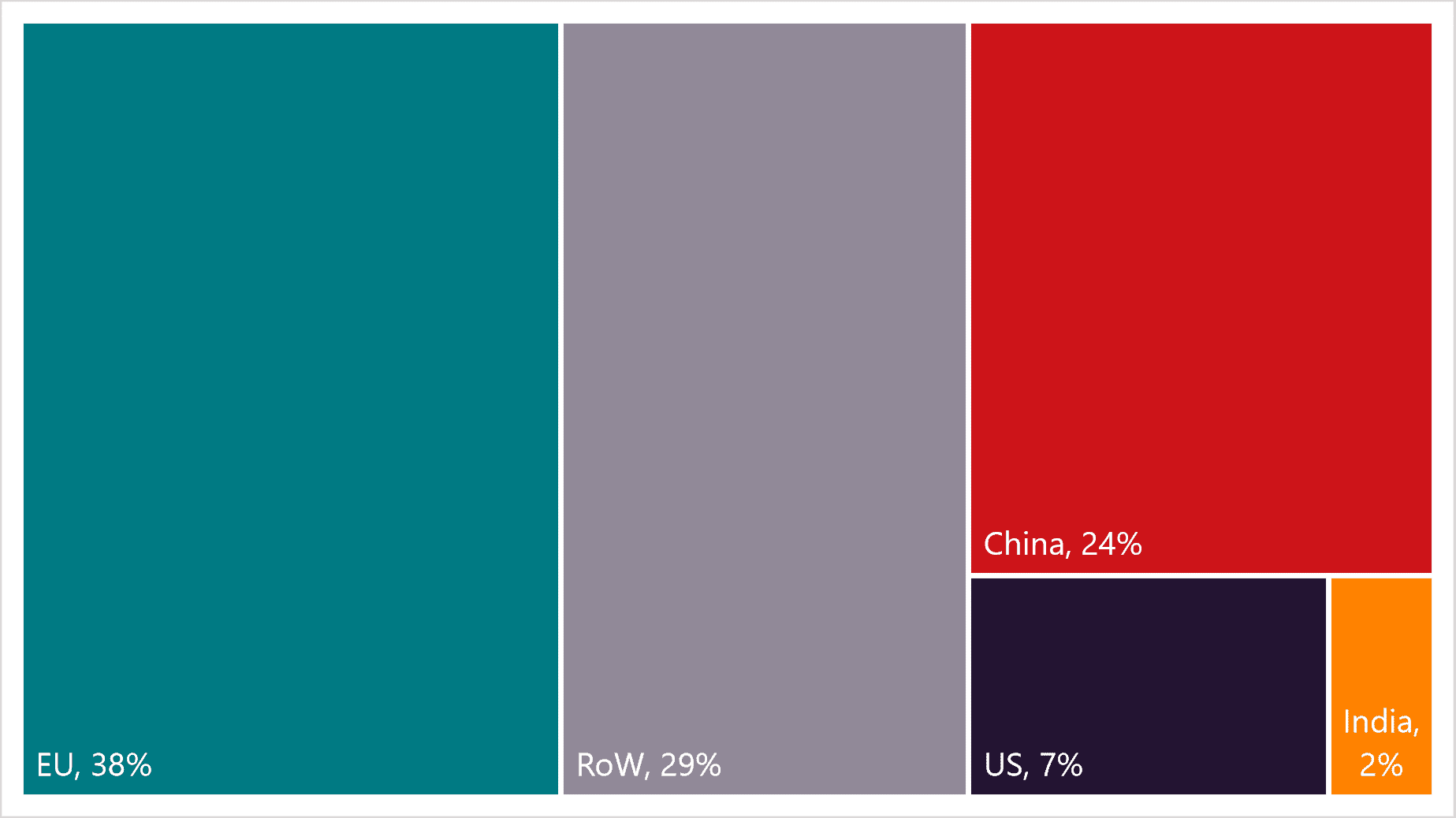

Under Modi 2.0 from 2019-2024, the manufacturing sector was once again established as the centre of BJP’s election manifesto through the Self-Reliant India initiative. It aims to cut down import dependencies and gain a global market share in exports by increasing domestic manufacturing of essential goods. India has made some progress on increasing its share in global exports of manufactured goods. Between 2019 and 2023, India’s exports of manufactured goods as a share of global exports increased from 1.8 percent to 2.1 percent. However, this value is nowhere close to the share of large global exporters such as China, the US, and the EU in 2023 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Share of the largest exporters of manufactures products (2023)

Source: UN Comtrade, Author’s calculations

In terms of overall economic growth, India’s GDP after the Covid-19 pandemic grew at a phenomenal pace of an average of 8.1 percent between 2021 and 2023. Yet, GDP growth does not capture the nuances of India’s economic reality. Despite rapid economic growth, inequality in India has remained at an all-time high. Some estimates show that by the end of 2022-2023, the top 1 percent of the population held 22.6 percent of income and 40.1 percent of wealth in India[1]. This inequality has been especially pronounced during the BJP’s rule.

In addition to this, India is also seeing high levels of unemployment. Despite, being the most populous country in the world with a large demographic dividend, India has been unable to harness it’s human capital resources. Under the Modi government, employment in the manufacturing sector has declined by 46 percent from 2016-17 and reached 27.3 million in 2020-2021. This has been the result of two major occurrences. The first is demonetization, where in 2016 the Modi government took the Rs. 500 and Rs. 1000 denomination currency notes out of circulation in an attempt to counter corruption. However, this also led to an acute shortage of cash, severely impacting jobs in the manufacturing and construction sectors. As India looked to rebuild, it was hit with the Covid-19 pandemic, once again leading to a steep decline in jobs in the manufacturing sector, particularly the labour-intensive manufacturing sector. There was a reversal in labour-flow with many workers returning to the agricultural sector. Although, India has seen rapid GDP growth, the government has been unable to create the jobs required to transform this growth into socio-economic benefits for all. The situation is also exacerbated by structural issues in the economy, such as a mismatch between the skills of the workforce and the needs of the industry, with limited spending on building human capital.

Despite the political and economic reality, Modi remains popular, clear from his return to power for a third time. However, in his third term, he will have to ensure that the focus on the manufacturing sector reaps results through increased employment, decreasing inequality, and a growing share of global manufacturing exports that can compete with China.

Modi 3.0 – a test of the manufacturing era

Modi 3.0 is characterized by a coalition government as well as a stronger opposition. This can have several consequences for the Indian economy. First, it might mean that the economic reforms pursued by the NDA over the past decade face a slowdown – the BJP will no longer have the freedom to implement its agenda as it did with a clear majority – dictating changes in the country’s vision unilaterally. Second, it could also result in more equitable growth due to more comprehensive and widely accepted policies. The Congress’ election manifesto focused on labour law reforms to achieve full employment and high productivity gains. With a stronger opposition, there is a higher likelihood that current deficiencies will be addressed. The top-down approach will transform into a consensus-driven process.

India’s new government structure could therefore mean a renewed focus on job creation and equitable growth. At the same time, under the Modi government, the focus on manufacturing and displacing China would still remain a priority. The goal would therefore be to harness the manufacturing sector to drive better socio-economic results as well as the rise to global prominence, particularly by encouraging diversification away from China and towards India.

India’s plans to establish itself as a capable substitute for China as a global supplier of manufactured products has resulted in several economic strategies. The first is the Made in India program which aims to replace Made in China and focuses on encouraging domestic production of goods for the global market while also meeting domestic demand in India. Another strategy aims to promote India as the prime candidate for the new economic policy of friend shoring of supply chains at the expense of China. The government plans to attract companies that want to diversify their operations away from China due to regulatory and strategic risks. However, there lies an inherent problem in these strategies which has in the past also posed significant challenges to India’s labour intensive manufacturing sector – complex labour laws.

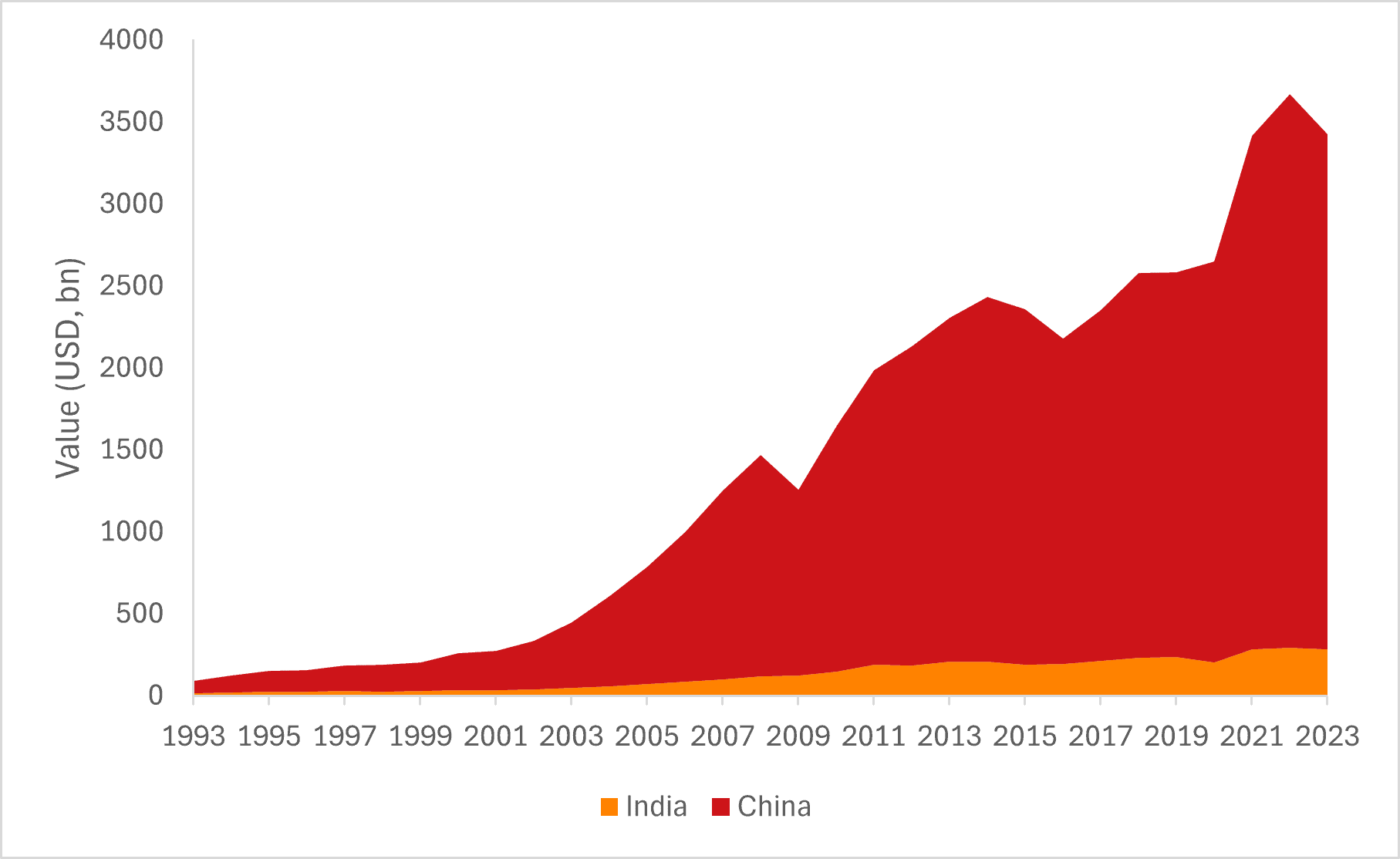

India and China adopted economic reforms around the same time – in the 1990s. While China’s economic reforms led to flexible and business friendly labour laws that drew in large investments in the labour intensive manufacturing sector, India’s labour laws till today present a challenge to foreign investors. This is also clear from the growth of manufacturing sector exports of India and China. Over the past twenty years, between 1993 and 2023, China’s exports of manufactured products to the world have grown by more than 4,000 percent. Meanwhile, India has only seen an increase of a little more than 1,500 percent (Figure 2). As India now tries to play catch up, China has moved ahead to focus on higher added value sectors such as services. However, the current situation could present a rare opportunity for India to fill the deficit left by China as a major global supplier of manufactured products.

Figure 2: Global exports from China and India of manufactured goods (2013-2023)

Source: UN Comtrade, Author’s calculations

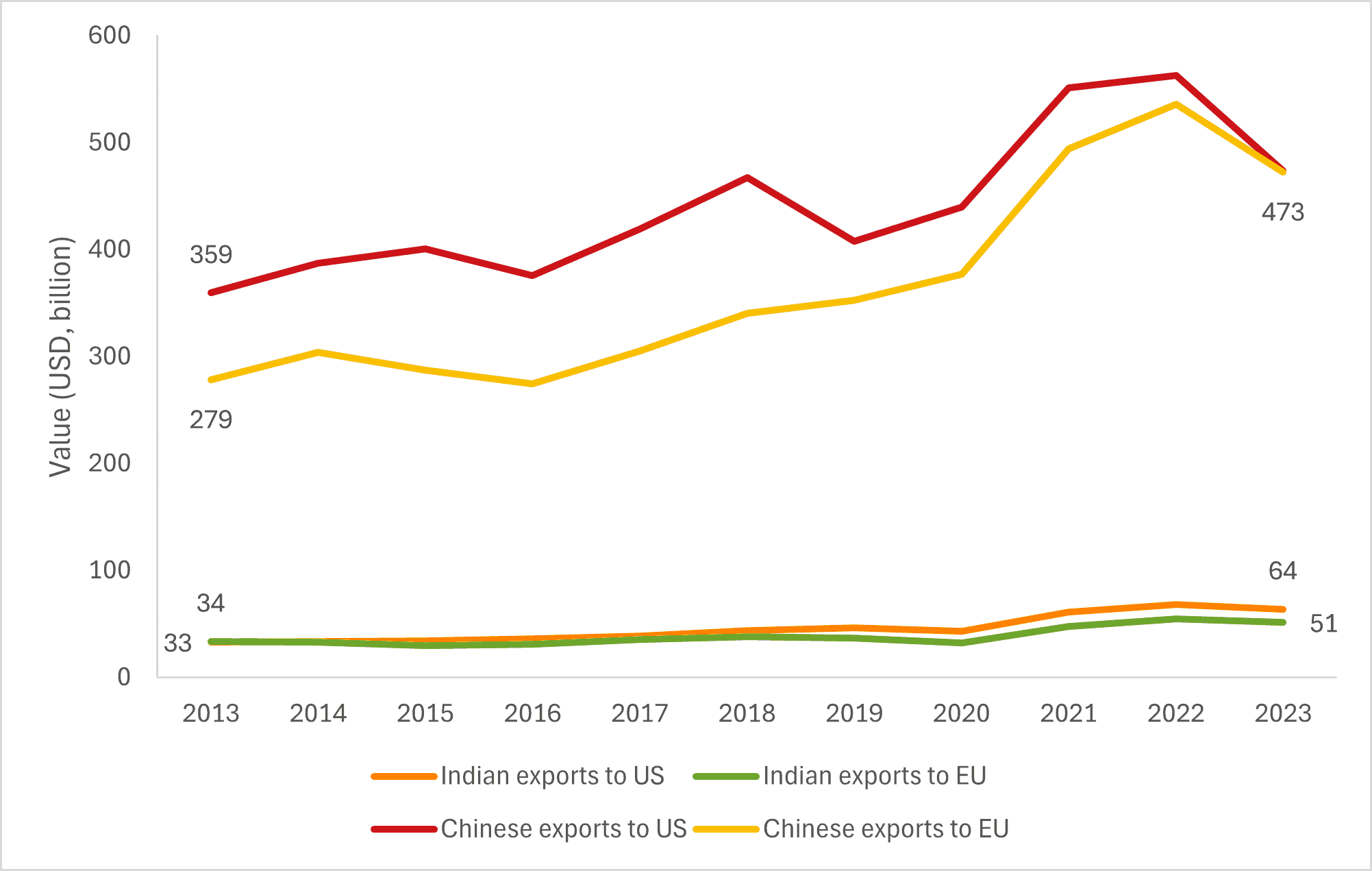

On the heels of the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the NDA has also been busy promoting the US led West + India industrial cooperation model in place of the US led West + China model. It aims to exploit the security anxiety of the US led West in forming economic relations with Russia and China. This is a tough proposition considering that in 2023 China’s supplies to the US and the EU were more than eight times that of India (Figure 3). Moreover, India’s global export capacity in 2023 ($ 284 bn) only amounted to three times of China’s exports to the EU and the US in 2023. However, it is also surprising to note that over the past ten years India’s exports to the EU and US have increased faster than that of China’s (by 73 percent compared to 48 percent respectively). The US followed by the EU are also the largest importers of India’s manufactured products.

Figure 3: India and China’s exports of manufactured products to the EU and the US (2013-2023)

Source: UN Comtrade, Author’s calculations

Clearly a lot needs to improve if India aims to replace China as a global manufacturing giant. At the same time, India also needs to tactfully convert its strategic partnerships into stronger trade relations. Even if the NDA government is able to significantly increase India’s manufacturing capabilities, in order to harness them it will need to focus on improving trade relations with partner countries. Trade policy would have to become a critical area of focus for the new government. There should be a strong consensus on the need to negotiate and finalize pending and new trade agreements that can enhance market access for Indian manufactured goods.

Conclusion

The Modi government has once again established the manufacturing sector as the central tenet of its economic policies. The goal is to expand manufacturing to not only feed domestic demand, but also drive exports and subsequently export-led growth. However, by virtue of being in the spotlight, the manufacturing sector is also burdened with additional responsibilities, prime of which are reducing income inequality and unemployment in the country as well as displacing China as a global supplier of manufactured products.

A stronger opposition and a coalition government might mean more consensus driven policymaking which can help address the pressing socio-economic challenges, however it will also mean that the Modi government will have to prove that its gamble on the manufacturing sector can pay off.

[1] Due to the lack in official data on poverty and employment since 2011, there are varying estimates of poverty. And the actual data behind the government’s estimates have not been released for independent analysis.