Published

How Valuable Is WTO Transparency: The 15 Trillion Dollar Question

By: Lucian Cernat

Subjects: European Union WTO and Globalisation

Lucian Cernat is Head of Global Regulatory Cooperation and International Procurement Negotiations at DG TRADE. The author would like to thank Peter Ungphakorn, Aitor Montesa Lloreda, and Olivia Mollen for their valuable inputs and suggestions. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Imagine you’re a small business interested in finding new export markets. It may look like an appealing business strategy, especially if your domestic market is small. However, the appeal may quickly fade away when you realise that your product would then be subject to different, onerous regulatory requirements around the world. Let us take the example of a company interested in exporting certain household appliances. Chances are that rules may differ significantly from one country to another, both in terms of technical specifications, and testing and certification requirements. In fact, chances are that such products are subject to hundreds of legal requirements worldwide.

Yes, we live in a regulated and imperfect world. You may not realise it but, just like democracy, the alternative would probably be much worse. Rules are the basis of a well-functioning society. The same applies to trade rules and the global trading system. But not all rules are equal. Some are more fit for purpose than others. Some rules are easy to comply with, others are more demanding and costly. Some rules are voluntary or developed by market participants, others are mandatory and imposed by law.

Trade rules affect 15 trillion dollars of global merchandise trade flows annually. In such a complex world, no wonder that companies engaged in international trade value transparency and predictability. Business surveys confirm this. Perhaps even more important than the value of trade flows is the number of enterprises that depend on trade around the world. In OECD countries alone, there are over 1 million registered exporters, with many more companies exporting indirectly via wholesalers, distributors and freight forwarders. The millions of individual exporters and importers around the world are the nodes of the global trading system. And each of them needs transparency and predictable trade rules. Thus, over time, transparency became an important WTO function, although an underrated one.

The WTO seldom makes the headlines these days, and when it does, it is more often about its crisis than its achievements. Yet, if you are one of those million exporters and importers and wanted to navigate the complex rules affecting your products around the world, the WTO would be a good starting point, especially the ePing platform developed jointly by the WTO, International Trade Centre and United Nations. You may be prompted by a Google search to ePing, although that is not guaranteed (when I searched for “where can I find information about the technical and regulatory requirements applicable to my exports”, neither the WTO TBT database nor ePing came up first).

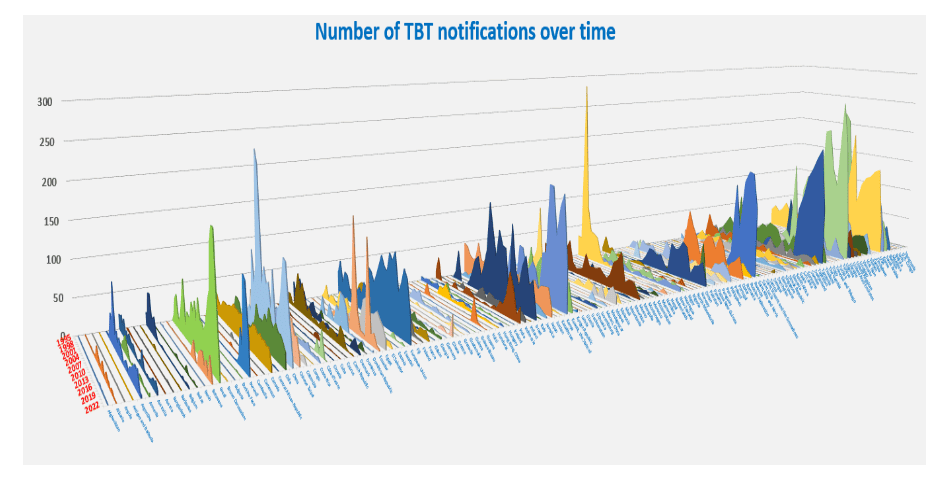

Now, let’s suppose that our prospective exporter of household appliances discovers the WTO TBT database and the ePing platform. At first, it may be a bit disconcerting to see that, overall, there are around 50’000 notifications under the WTO Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement (figure 1). That’s the number of times WTO members notified each other about new TBT rules that may affect, one way or another, trade flows for thousands of specific products. If you’re an exporter of kitchen equipment, you may have to scroll through over 700 TBT notifications. Cross-country regulatory divergence is not only an issue for complex equipment with strict safety requirements and many moving parts. Even for simpler products with no moving parts, like beverages, searching for wine labelling requirements across a range of export destinations can be a daunting task for a small wine exporter. Luckily, the WTO TBT database has it all at your fingertips, from Australia to Zimbabwe. With a little patience and curiosity, you soon realise that it is a goldmine of valuable information, answering such crucial questions that may determine compliance, or lack thereof, with the regulations in the export destination. The database can be searched by individual HS codes that are relevant for a particular exporter and then the number of results gets more manageable.

Figure 1. Number of new TBT notifications by WTO members, over time (1995-2022)

Source: Author’s calculations based on the WTO TBT notification database. The notifications of corrections, amendments and revisions to previous TBT notifications are excluded. WTO members are listed in alphabetical order.

Source: Author’s calculations based on the WTO TBT notification database. The notifications of corrections, amendments and revisions to previous TBT notifications are excluded. WTO members are listed in alphabetical order.

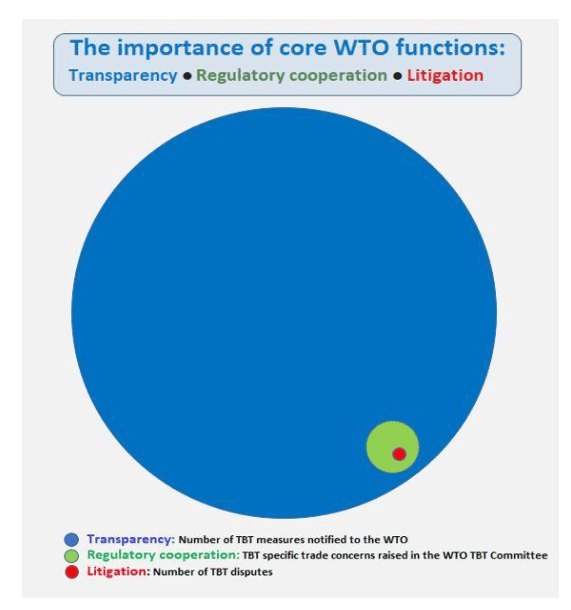

The WTO TBT database is not just valuable for exporting SMEs. It is immensely valuable for trade officials, who are tasked with ensuring that their fellow WTO members respect international trade rules. The transparency offered by the notification system greatly facilitates regulatory dialogue, promotes global regulatory cooperation and avoids formal trade disputes. The numbers in Figure 2 speak for themselves. Only a small proportion of the 50’000 TBT notifications are considered potentially problematic to raise specific trade concerns, and out of those concerns, only a tiny proportion led to litigation, since many of the specific trade concerns are clarified or solved via regulatory dialogue between WTO members. In the case of the EU, this regulatory dialogue facilitated by the WTO TBT specific trade concerns process helped remove barriers affecting over 80bn euros of EU exports over the last decade. This would not have been possible without transparency and is proof that the regulatory dialogue that takes place at the WTO often leads to a successful solution, without having to resort to litigation.

Therefore, the WTO TBT notification system functions like a public good. It’s a bit like sunlight: a free but essential element. And, like sunlight, transparency is the best disinfectant against unintended TBT barriers. Some might be tempted to think that transparency is not in everyone’s interest. But consider the alternative: without transparency, there would be less cooperation, more trade frictions, and more trade disputes. The WTO TBT notification system has largely achieved these trade facilitation objectives already and all its members should be proud of this collective achievement.

Figure 2. The importance of core WTO functions in the TBT area

Source: Author’s elaboration based on the WTO TBT databases.

But transparency could, and should deliver more. Let’s go back to our SME example. One important transparency feature for SMEs would be the “easification” of the entire process. The SMS notification by the WTO ePing platform telling you whether a new notification about an upcoming or new regulation affecting a specific product in a particular country is already a big step forward. Despite the valuable features offered by the ePing system, its use by the business community is far from its true potential. According to the UN International Trade Centre, there were around 13’000 users worldwide (the latest figures indicate over 21’000 users). The WTO mapped them: there were some 1200 in the European Union, over 500 in the United States and almost 400 in Vietnam (since 2021 ePing is also available in Vietnamese, alongside English, Spanish and French). Out of these ePing users, only 40% or so are business users, the rest being public officials and academics. Compared to the millions of exporting and importing firms worldwide, the current ePing user base looks too small to make it the “go to” place for business-relevant information on TBT or SPS requirements. This begs the question: why so few business users?

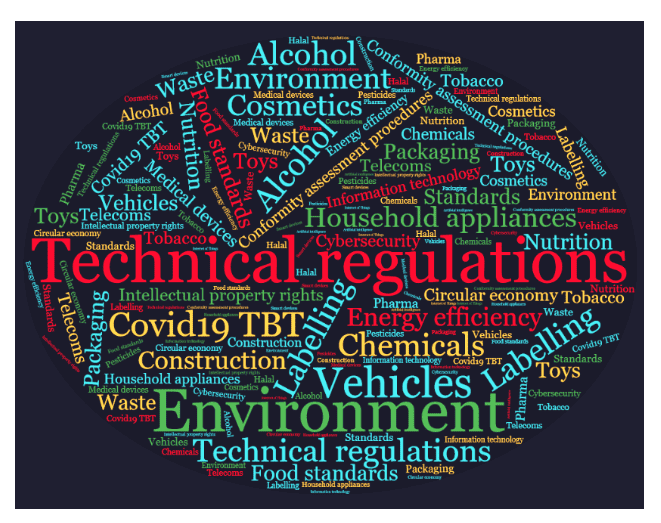

Apart from a lack of awareness, another reason that may explain the limited use of the ePing system is information overflow. No human can possibly digest 50’000 notifications, and the hundreds of thousands of pages of the underlying legal texts, affecting a wide range of sectors, spanning from alcohol, chemicals, toys, cars and medical devices and dealing with complex and technical regulations affecting standards, labelling, packaging and environmental and recycling requirements (figure 3).

Figure 3. The WTO TBT notifications: mapping the buzzwords

Source: Author’s elaboration based on the WTO TBT databases.

While the ePing SMS notification is a helpful “heads up”, it does not guarantee that the information provided is directly relevant for business users. However, the ePing basic notification system might be further improved, if combined with AI technologies we see nowadays deployed by ChatGPT and similar tools. A combination of text and image-based AI would let the system produce more accurate and relevant results. The transparency gains stemming from deploying AI tools could be considerable, assuming their current rate of progress. In a previous #TradeXpresso Lungo I ran a quick assessment of the current trade expertise of ChatGPT. For standard, legal text identification and interpretation it fared quite well already, but less so when asked to perform a more sophisticated legal analysis of specific provisions across several trade agreements.

Now imagine a specific “chatTBT” tool powering the ePing system fed with the 50’000 WTO notifications and TBT-related legislation in all WTO members, plus the relevant WTO legal texts and jurisprudence. Then, on top of the full legal background, add all the Harmonised System taxonomy used by trade and customs officials, and several product-specific parameters (e.g low vs high-voltage electrical equipment, smart vs analog devices, safety parameters, etc.). That would allow the AI tool to filter through all possible options and offer relevant, personalised advice for a specific exporter to ensure compliance with TBT requirements in any WTO member. This would narrow down the irrelevant notifications for individual companies and maximise the returns for exporters using the WTO TBT notification system. The system would enter into the emerging, firm-level “Trade Policy 2.0” tools that are developed elsewhere.

Reaping the benefits of AI would also help reduce the notification disparities among WTO members. As seen in figure 1, many WTO members have made only scant use of the TBT notification system: some 60 WTO members have submitted, on average, less than one TBT notification per year since 1995. The use of TBT-specific AI tools could also help those countries with presumably limited administrative capacities that have so far made little use of the TBT notification procedures, e.g. in LDCs. A trade official that is a designated TBT enquiry contact point in the national administration of an LDC could rely on a AI-generated WTO notification about the latest legislation or upcoming draft technical regulations in preparation in that country, ready to be validated and submitted to the WTO secretariat in accordance with the TBT rules.

This may sound as a far-fetched scenario, but such advanced technologies are already becoming a reality. Anyway, with AI functionalities or not, transparency is a topic deserving more attention in the ongoing debate about the modernisation of the WTO system. Some concrete, albeit technologically modest, proposals have been floated already by WTO members, including by some countries that, so far, were not among the most active users of the existing TBT notification process.

This is encouraging. When looking at what the WTO has achieved so far, it is clear that transparency is useful and we need more of it. But we don’t just need more transparency —we need more valuable insights from it. And, in the absence of big rounds of multilateral negotiations, we need to ensure that the WTO remains relevant for the millions of companies engaged in global trade. The surest way of doing this is ensuring that transparency requirements for complex TBT requirements are translated into business-friendly, relevant information. Let’s “chatTBT”!