Published

EU’s Dependency Problem on Russian Oil and Gas

By: Oscar Guinea Vanika Sharma

Subjects: Energy European Union Russia & Eurasia

Russia’s war on Ukraine has started a new discussion about Europe’s energy dependency on Russia.

In an upcoming ECIPE policy brief, we develop a conceptual framework and indicators to measure trade dependency, including on energy products. We propose two indicators to measure trade dependency. The first indicator measures the share of EU imports from outside the EU over EU production proxied as the sum of EU imports and exports, while the second indicator considers the market concentration of EU suppliers using the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI). We apply this framework to EU trade with the rest of the world in 2020 and elaborate on the product categories and partner countries behind these dependencies. From a total of more than 9,000 product categories, there were only 233 products that could be classified as dependent. Imports of hydrocarbons from Russia are part of this list of trade dependencies.

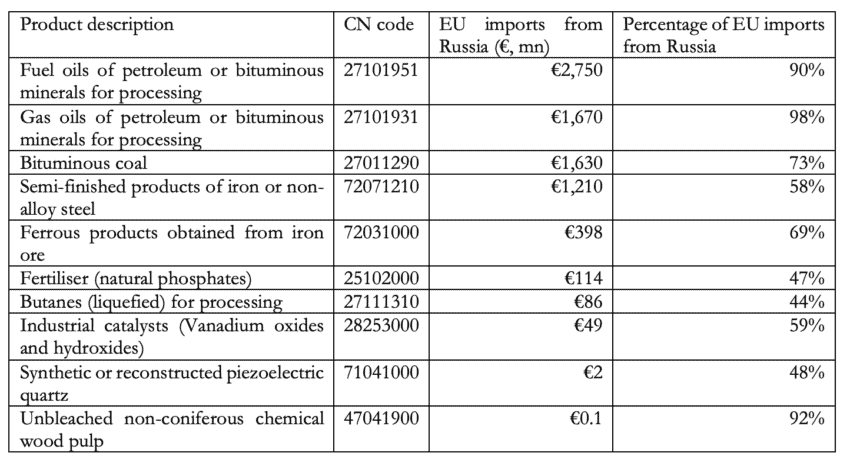

The EU depends on Russia for the supply of ten product categories that represent a total value of €8 billion. Table 1 presents these products, their imported value, and the percentage of the EU imports coming from Russia. As a result of EU’s dependency on Russia for these products the EU has been unable to impose heavier sanctions on Russia’s main export and source of income – oil and gas. In previous blogs, we showed that Russia is also dependent on EU exports and that dependency will be hard to unwind.

Table 1: EU import dependency on Russia’s exports (2020) Source: Eurostat. Authors’ calculations. Note: product description has been shortened.

Source: Eurostat. Authors’ calculations. Note: product description has been shortened.

What can the EU do to lower its dependency on Russian hydrocarbons? In our forthcoming policy brief we present three basic actions to lower trade dependencies: (1) stockpile; (2) subsidise domestic production; and (3) trade. These three actions are similar to the policies outlined by the European Commission’s REPowerEU strategy and the IEA’s ten-point plan to lower EU’s dependency on Russia’s oil and gas.

Build strategic reserves (stockpile)

EU businesses and governments can choose to build inventories of the dependent products, so that they do not face shortages in times of crisis. Gas storages can provide insurance against unexpected events, such as surges in demand or shortfalls in supply, that cause price spikes. The European Commission will present a legislative proposal requiring underground gas storage across the EU to be filled up to at least 90 percent of its capacity before 1st October each year.

Invest in renewables and energy efficiency (subsidise domestic production)

The EU and EU member states could incentivise businesses to produce the dependent products within the EU. Several of the 10-point measures proposed by the IEA will substitute Russian gas for energy produced (or saved) within the EU. Among these measures are the deployment of wind and solar projects; generation of electricity from bioenergy and nuclear; replacement of gas boilers with heat pumps; investments in energy efficiency; and saving energy by, for example, lowering the thermostat.

Find alternative suppliers (trade)

The EU could lower its dependency by buying the products in which the EU is dependent from other countries. This is the most prominent strategy for reducing the dependence on Russian hydrocarbons. The European Commission has proposed to diversify gas supplies, via higher Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and pipeline imports from non-Russian suppliers.

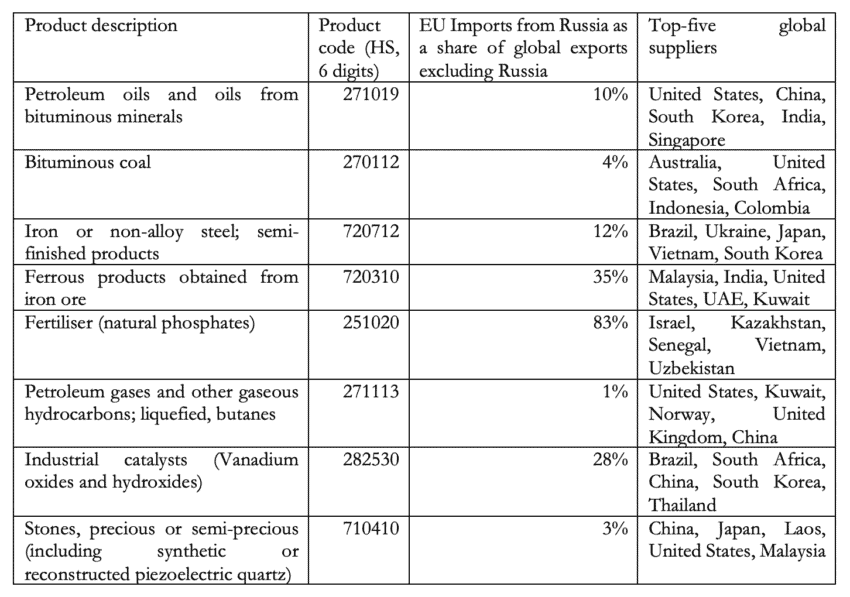

Table 2 presents the product categories from the previous table, although this time at a higher level of aggregation since data for the most detailed product categories of Table 1 is not available for countries outside the EU. Table 2 shows the percentage of EU imports from Russia as a share of global exports – excluding Russia’s exports to the world – and the five largest global suppliers for each product. For the eight product categories included in the table, the available global exports were always higher than the amounts that the EU imported from Russia.

However, global exports are sold somewhere else and therefore are not really available. Moreover, for some product categories – particularly some kinds of fertiliser – EU imports from Russia represent a substantial share of global exports. For other products, such as gas, countries require certain infrastructure to receive these products from alternative suppliers, which lack of it can lead to shortages even if global markets can supply this product. Yet, Table 2 shows a static picture based on past trade patterns. Products in demand could be produced in new locations and extractions in current locations could be increased. Moreover, present dependencies are not necessarily the future ones as the EU is likely to lower its absolute consumption of hydrocarbons.

Table 2: Available global exports of products in which the EU depends on Russia’s exports (2020) Source: UN COMTRADE. Authors’ calculations. Note: product description has been shortened.

Source: UN COMTRADE. Authors’ calculations. Note: product description has been shortened.

As the EU has experienced first-hand after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the concentration of market power in the production of any product carries geopolitical risks. In the case of Europe’s dependency on Russia oil and gas, this dependency has come at a cost as the EU has not been able to impose sanctions on Russia’s most profitable sector. Yet, the policy measures put forward to lower this dependency show that trade dependencies are a tractable problem.