Published

#ECIPEdebates: Will Malmström Change the Course of EU Trade Policy?

Subjects: EU Trade Agreements European Union

Following the nomination of Cecilia Malmström as the new European Commissioner for Trade, ECIPE asked its Twitter followers whether the new Commission would change the course of EU trade policy. In light of yesterday’s EP hearing, we evaluate the responses and conclude that both the Yes- and No-camps might claim their predictions have been confirmed.

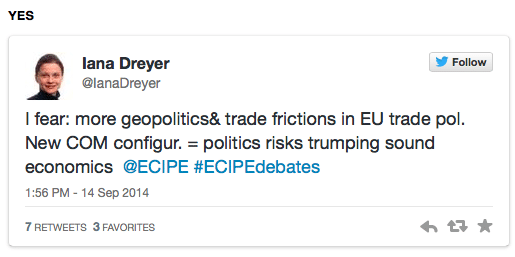

According to Iana Dreyer, Editor-in-Chief at Borderlex.eu, the new Commission configuration could lead to an injection of geo-politics in a policy area that is supposed to be based on sound economics. This traditional idea that trade policy-making should be insulated from political/public pressure to avert protectionism and beggar-thy-neighbour policies has been the foundation of the EU’s institutional set-up in trade, making it one of very few areas in which the Commission has firmly been in the driver’s seat since 1957.

Effectively elected by the European Parliament, new Commission president Juncker has vowed to increase the democratic legitimacy of the EU’s executive by increasing the EP’s powers, including in the area of trade. Citing the “Political Guidelines” he presented to the EP in July as “somewhat akin to a political contract”, his letter to Trade Commissioner-designate Malmström listed enhancing transparency towards citizens and the European Parliament during all steps of the negotiations as one of six priorities.

The European Parliament already gained more powers in trade through the Lisbon Treaty, as its consent is now required to conclude FTAs. Under the consent procedure, the Parliament is limited to an up-or-down vote and cannot make amendments. However, the assembly’s rejection of ACTA has shown that MEPs are not afraid of using the nuclear option if a trade deal prompts stark public opposition.

Those who see the appointment of Juncker as yet another step towards the complete politicisation of EU trade policy will certainly have discerned elements corroborating their views in yesterday’s hearing. Malmström used most of her opening 10 minutes to appease those MEPs who expressed concerns about environment, health and consumer standards, which she vowed to “never trade against economic concessions”. On ISDS, she admitted that it could be improved, without ruling out its inclusion in TTIP, as the original version of her written answers to the EP had promised.

In addition, she promised to increase transparency during the negotiations of trade deals by publishing her list of meetings with stakeholders, and more importantly, by sharing negotiating documents with all 751 MEPs. So far, only the members of the Committee on International Trade (INTA) had access to these. Malmström conditioned the commitment on the Parliament creating “a system that ensures confidentiality”, but seems to have opened the door for a strong increase in interference from the EP during trade negotiations.

On the other side of the debate, Dr. Gabriel Siles-Brügge, Lecturer in Politics at the University of Manchester, predicted no change of course in EU trade policy to take place, other than an increased focus on “selling TTIP”. Recent academic literature offers two explanations as to why the appointment of a new Commission(er) cannot drastically alter the EU’s trade course or agenda.

A first strand of thought argues that while institutions play a role, economic interests are the dominant drivers of trade policy. In a world economy marked by increasingly globalised supply chains, this means that exporters will tend to lobby in favour of trade openness and liberalisation, as tit-for-tat protectionism would be highly damaging to their businesses. This rationalist view makes abstraction of the policy ideas and values of political agents, but instead considers trade policy as defined by the balance of domestic economic interests, which in a strongly integrated market such as the EU would generally tip in favour of global exporters.

A second explanation, as offered by Dr. Siles-Brügge himself in a recent paper, looks at ideas rather than interests. Siles-Brügge argues that trade policy-makers “construct” the political reality by creating an ideational imperative that limits the policy debate. By pointing out the abject failure of protectionist policies in the past, political leaders rule out a whole spectre of trade policy and consistently frame continued openness as the only option that creates jobs and growth.

Evidence for this view could be found yesterday as well, when French MEP Yannick Jadot (G/EFA) suggested taking a break in on-going FTA negotiations to evaluate the wider EU trade strategy as there is no proof that it has created “millions of jobs”. Malmström replied that she has a different point of departure and that she thinks trade is “a very powerful tool to get out of the economic crisis”. Earlier, she illustrated what Siles-Brügge means by “ideational imperative” when she equated “trade policy (…) driven by the interests of citizens” to being ambitious in trade negotiations “in order to create jobs and growth”.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Watching yesterday’s discussion between Commissioner-designate Malmström and INTA members, some will conclude that trade policy will never be the same again. The new trade commissioner has opened the door for increased political interference from the EP by giving it more power and addressing its concerns on TTIP. Many trade economists might therefore rue her contribution to the politicisation of a policy area that is traditionally considered better off in the safe hands of experienced bureaucrats.

The main question is however whether politicisation in this form is necessarily a bad thing. Based on the Lisbon Treaty (Art. 207 TFEU), it is the right of every MEP to be kept abreast of trade negotiations, as it is not specified that only the INTA should be consulted by the Commission. It may prove a great move by Malmström to sell this as a favour to the Parliament now, rather than having to reluctantly concede it later down the line. It will certainly make MEPs less susceptible to the “behind-closed-doors” criticism that drives the opposition against TTIP.

Moreover, increasing democratic legitimacy seems an inevitable consequence of the expanding scope of trade policy. Instead of brokering deals on obscure tariff lines, trade negotiators now deal with issues such as intellectual property, investment protection and services regulation, i.e. policy areas which lie closer to the core of the nation state. Involving a democratically elected body in this process from the earliest stages will undoubtedly lead to protracted negotiations, but could also serve to bring legislators on board of the “ideational imperative” of trade openness in the long run.

All in all, Malmström did not deviate much from the lines taken by her predecessor Karel De Gucht. While she was lenient on process and struck a more diplomatic tone – at times the hearing seemed nothing short of a conversation – she stood firm on substance. If her transparency measures will be what ultimately draws the Parliament over the line in support of ambitious trade deals, Malmström’s strategy of openness may yet end up saving the EU’s trade agenda rather than jeopardising it. To be continued.