Published

Assessing UK Trade Policy Progress

By: David Henig

Subjects: UK Project

Summary

We see signs of progress in preparing the UK for greater trade policy freedom outside of EU membership, such as a few agreements reached to replace existing EU Free Trade Agreements, and a process for determining the rollover of trade remedies that was considered to be well run.

However this progress has been insufficient for business and other stakeholders to feel confident that the UK is ready for the challenges ahead across the entire trade policy space. This is largely a reflection of continued secrecy, given how little has been revealed in terms of policy goals or even why priorities have been chosen. Trade policy can no longer be a largely secret exercise, and positions need to be revealed, tested and consensus established before we can safely say the UK has the right foundation for successful negotiations.

Introduction

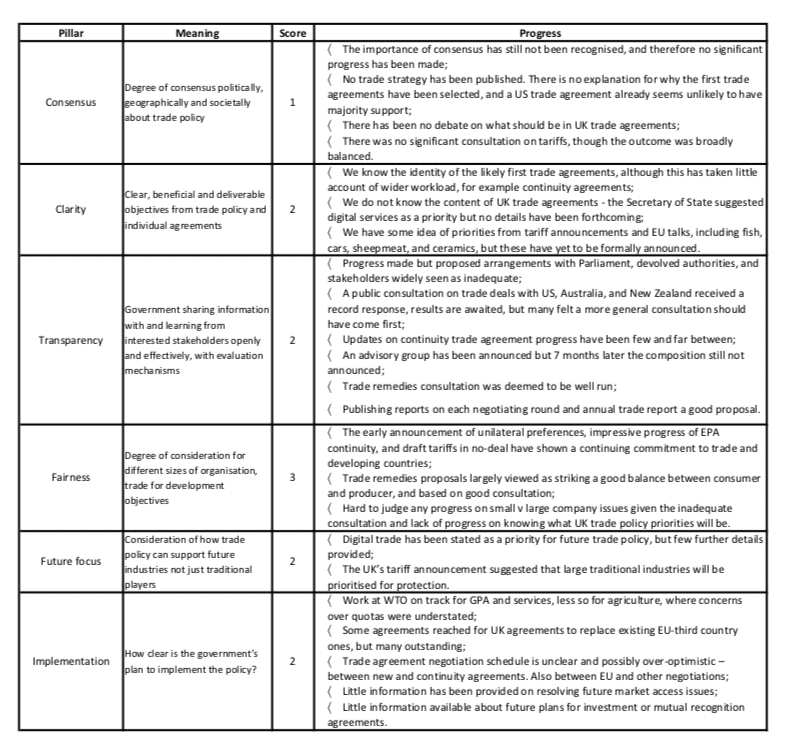

In April 2018 we published the report “Assessing UK Trade Policy Readiness” which identified six pillars of trade policy that needed to be considered in determining whether a country’s trade policy was on track. The report concluded that “It is perhaps unsurprising that the UK has not yet made sufficient progress in developing an independent trade policy almost from scratch. The Brexit process is putting tremendous pressure on resource and political bandwidth, which any country would struggle to manage. Nonetheless it is disappointing that there are so few areas in which the UK government appears to be ready to openly discuss trade policy as a prelude to deployment.”

We also promised to update this on the eve of the expected date for the UK leaving the EU. It now looks likely that March 2019 will not be the UK’s departure date, none the less this anniversary of the original paper provides a useful opportunity to take stock of progress.

It should be noted that, whilst not intended to measure the progress on the EU negotiations, these pillars nonetheless provide one indication, as well as testing the usefulness of the pillars approach. The continued absence of consensus, the first pillar, has indeed become increasingly critical to the failure to progress, as the approach would suggest.

2019 Analysis

The analysis of progress draws on publicly available information, such as departmental updates, ministerial speeches, parliamentary debates, and answers to parliamentary questions. Clearly there will always be much work going on behind the scenes, but this cannot be considered seriously until it is revealed and thereafter tested.

It remains the case that the UK government is reluctant to openly discuss too much detail on trade policy, for example in terms of policy priorities. We believe that much progress has been made at official level, but until this is revealed and scrutinised we cannot consider UK trade policy to be sufficiently mature to be the basis for negotiation of new trade agreements. As an illustration of this, there has been considerable recent comment on the problems that a UK-UK trade deal would face, particularly with regard to food standards, but no sign of acknowledgement of this. Unless the issue can be properly debated problems are being stored for a later date.

(see scale below)

Looking forward

These scores are similar to those recorded in our first exercise, reflecting the same underlying issue of government secrecy. This has prevented in particular the establishment of any sort of consensus, indeed the consideration that it is necessary, and fixing this is the most urgent requirement for UK trade policy. We have seen from Brexit negotiations what can happen if this does not happen, in terms of the struggle to pass agreements through Parliament. The same will happen for trade agreements, particularly with the US, unless there is a change of approach.

To build consensus there is a need to for a considerable increase in transparency. The proposed arrangements for parliamentary consultation, while welcome, are inadequate for modern trade agreements. The failure to update on progress in continuity arrangements has damaged trust. The absence of an overall trade strategy which sets out departmental priorities a mistake. Until these things happen the UK cannot have a successful trade policy.

In many ways the lack of transparency is acting as an obstacle to UK trade policy being sufficiently mature to be ready for negotiations. Much work has been done defining policy positions, but until this can be publicly tested, it will not be sufficiently robust to be a basis for future trade agreements. A change of approach in this area would yield significant benefits for Government.

We also need to see, perhaps in a strategy, an overall implementation plan. Potential trade partners are already telling us that negotiations will not proceed far until there is clarity on future UK-EU relations. These new negotiations will also need to compete with continuity negotiations such as with Japan and Turkey. It is hard to see how a new deal with New Zealand is more important than continuing a deal with Japan.

Conclusion

Our framework allows us a basis to judge UK progress on objective grounds. We can note progress, and the undoubted hard work behind the scenes, while identifying that this is not yet sufficient. There is no doubt that the UK’s trade policy challenge in leaving the EU is immense and would challenge any Government, but equally there is no reason why over time the UK cannot be successful. However this will require changes in approach, not least in becoming considerably more open.

Annex: Scale

- No clearly identifiable work being undertaken: The importance of this pillar has not been recognised, and we can see no sign of related work. The reality of the pillars is that this score should be unlikely;

- Discussion in progress: We can see from references made by ministers, officials, and others that work has started in this area, and they recognise the importance of it. There does not as yet seem to be any conclusions to this work however, or obvious gaps that mean it cannot be said to be stable;

- Stable position: There is a settled and defensible position in this pillar, it may not yet have been tested in negotiations, but it should be ready to be so;

- Operational: The government is negotiating on the basis of agreement in this pillar, this would be where most governments should aim to be;

- Delivering successfully: There are successful results of trade policy in this area, whether for the economy as a whole, specific business, or other interests.