The Tragedy of International Organizations in a World Order in Turmoil

Published By: Guest Author

Research Areas: Far-East North-America WTO and Globalisation

Summary

By Jean-Jacques Hallaert, Member of the Groupe d’Economie Mondiale (GEM) at Sciences Po.

China’s rise and the U.S. response to the perceived threat it represents to its predominance jeopardize the world order and affect international institutions. The paralysis of the WTO and the U.S. withdrawal from the WHO are the most visible examples, but not the only ones. This article presents the case of the International Monetary Fund.

Quotas are the cornerstone of IMF governance. They determine each member’s contribution to the institution’s resources and their voting power. As the world evolves, the quota distribution needs to be adjusted.

Adjustments in quota shares and thus voting powers have always been politically difficult. However, they were possible. In the early 1990s, members agreed to an increase in the representation of Japan. In the 2000s, they agreed to increase substantially the voting power of emerging economies. In contrast, the 15th General Review of Quotas concluded early 2020, failed to increase and realign quotas. The proximate cause for this was the opposition of the United States to a change in quotas. This paper argues that the U.S. decision was in large part motivated to prevent an increased influence of China.

The failure to increase and realign voting powers may have long-lasting consequences. In the absence of a quota increase, the IMF will need to continue to rely on borrowed resources to avoid a drop in its lending capacity. This extension of the “temporary” recourse to borrowed resources undermines the governance of the Fund as voting powers (which are not linked to borrowed resources but only to quotas) are disconnected from member’s total contributions to the Fund and to their economic weight. This may trigger a new legitimacy crisis and provide incentives for countries like China to support the development of new and competing institutions which would better represent their interests and economic weight. Such a development would undermine the complex and fragile international financial architecture.

The author gratefully acknowledges Patrick A. Messerlin for his support and advice. The views expressed herein are those of the author.

1. Introduction

International organizations embody a world order. They are its visible face, reflect its values and principles, and their mandate is often to enforce its rules of the game. For them, a world order in turmoil is significant challenge. This is currently the case as a result of China’s rise and the United States answer to the perceive threat it poses to its hegemony.[1]

This article focuses on the case of an international organization that the G20 routinely presents as being at the center of the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN): the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[2] It starts by briefly discussing the U.S. and China views of the current international system before turning to lessons of history. How did the IMF adjust to Japan’s rise in the late 1980s? How did it give more representation to emerging markets (EMs) in the 2000s? These successes are then contrasted with the recent failure to adjust to China’s rise and its implications.

[1] “The word hegemony is used in diverse and confusing ways” (Nye, 2015). I adopt the definition of Lebow and Valentino (2009) and Temin and Vines (2013): hegemony is the capacity of a country to order the international system (sometimes to suit its interests) or in other terms the capacity to establish the rule of engagement between countries and promote cooperation between countries.

[2] For a description of the GFSN and its recent mutations, see Denbee et al. (2016).

2. A World Order in Turmoil

China is unwilling to accept American leadership or hegemony in the world; the United States is unwilling to accept China leadership or hegemony in Asia. For over two hundred years the United States has attempted to prevent the emergence of an overwhelming dominant power in Europe. For almost a hundred years […] it has attempted to do the same in East Asia. The emergence of China as a dominant regional power in East Asia […] challenges that central American interest.

(Huntington, 1996)

The world order is in turmoil as a result of escalating U.S.-China tensions, which illustrate a well-documented dynamic: changes in relative economic powers create tensions between a rising power and a declining one (Kennedy, 1987). As a change in relative economic power is a slow process, it is no surprise that U.S.-China tensions are not new but appeared in the early 1990’s (Huntington, 1996). They are not unprecedented either: in the 1980’s, it was Japan’s rise which triggered bilateral tensions.

Kennedy (1987) points that the U.S. relative decline is inevitable but “a long time in the future.” Recently, Mearsheimer (2014), Nye (2015), and Shambaugh (2013) also argued that China will not be in a position to threaten the U.S. predominance before long. However, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) heightened the perception of a decline. Temin and Vines (2013) claim that “the Great Depression marked the end of the British century, just as the recent crisis signals the end of the American century.” They see the GFC as an “end-of-regime crisis,” a crisis that “marks (in retrospect) the end of an hegemonic power.” In addition, as the GFC was mostly a transatlantic crisis, it triggered questions on the suitability of the U.S./Western model. In its aftermath, large EMs demanded more forcefully to be given a greater representation in international organizations. In the case of the IMF, Mohan and Kapur (2015), who represented India at the IMF’s Executive Board, argued that, before the GFC, “the IMF member countries got grouped in two relatively distinct groups, debtor countries (mostly EDEs [Emerging and Developing Economies]) and creditor countries (mostly AEs [Advanced Economies]), and it was therefore natural that AEs would have a more dominant governance role.” The GFC produced a dramatic change as “many EDEs are now counted among the group of creditors, and AEs among the debtor countries group.”

“Making America great again” is a reaction to U.S. relative decline. U.S. policies are increasingly unilateral, conflictual, and undermine the world order and Kennedy’s advice is worth remembering: “The task facing American statesmen […] is to recognize that broad trends are under way, and that there is a need to ‘manage’ affairs so that the relative erosion of the United States’ position takes place slowly and smoothly, and is not accelerated by policies which bring merely short-term advantage but longer-term disadvantage. […] the only serious threat to the real interests of the United States can come from failure to adjust sensibly to the newer world order” (Kennedy, 1987).

In this context, it is useful to elaborate on the attitudes of the U.S. and China toward the current world order and international organizations.

2.1. The United States

The U.S. has grown to see the system of international organizations and treaties that it has instigated as not supporting anymore its interests but rather as enabling the emergence of a challenger. Thus, it loses incentives in providing leadership, hampers the functioning of some organizations, and withdraws from many international treaties.

This is an exacerbation rather than a reversal of U.S. policy. For example, “In its first two years, the George W. Bush administration walked away from more international agreements than any previous administration. (Undoubtedly, that record has now been surpassed under President Donald Trump)” (Zakaria, 2019). In the international financial domain, the “on-the-whole negative prospect for international cooperation” was strong in the early stages of the Bush administration. Eventually, events forced the U.S. to change its views. “In its first months, Turkey faced a renewed crisis, and the United States called on the IMF to restart its program with Turkey on a larger scale. The same happened subsequently in Brazil and several other countries. At the end of the Bush administration, which tended to favor domestic financial deregulation, the United States promoted the G-20 to the level of presidents and prime ministers and supported the process that led to substantial if still incomplete reforms in international financial regulation” (Truman, 2017).

The Trump administration adopts a two-pronged approach when it comes to international organizations. If it believes that China’s influence is already large in an institution or that the institution serves China’s interests more than the U.S.’, it withdraws from that institution or paralyzes it. If it is not the case, it attempts to reinforce its influence. The World Trade Organization (WTO) suffers from the first approach as it is perceived in Washington as favoring China’s rise. In December 2019, the appellate body of the WTO became paralyzed as two of its judges retired while the U.S. blocks any new appointments. With only one judge left, the appellate body is not be able to hear new cases. This is also the case of the World Health Organization (WHO). In May 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic, the Trump administration threatened to cut permanently U.S. funding to the WHO unless major reforms were implemented and the U.N. agency demonstrates “independence from China” before announcing a few days later that the U.S. will terminate its relationship with the WHO because China has “total control” over the organization. In the case of the IMF, as argued below, the U.S. opposed a quota increase (Malpass, 2018; IMF, 2020b) to prevent a growing influence of China. This decision could also have resulted in a sharp reduction in the IMF’s lending capacity. However, as international developments (notably the Argentina crisis) showed that the IMF could serve U.S. interests, the U.S. supported maintaining the IMF’s lending capacity.

2.2. China

China’s is also ambivalent when it comes to the international architecture. On some occasions, China tries to reform international organizations from within to better reflect its interests and views. On other occasions, China chooses to create new institutions, undermining existing ones. This reflects a frustration with the current international system:

First, China believes that the rules of the world order do not reflect its interests. This is an ubiquitous theme as reported by Dempsey (2016), the former chairman of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff: “One of the things that fascinated me about the Chinese is whenever I would have a conversation with them about international standards or international rules of behavior, they would inevitably point out that those rules were made when they were absent from the world stage. They are no longer absent from the world stage, and so those rules need to be renegotiated with them.”

Second, China complains that the international order does not give it adequate representation. “Even as China has established itself as a rising global power and enthusiastic defender of multilateralism, existing institutions have often failed to give it its due.” (Zhou, 2019). In the case of the IMF, “China and other countries have grown wary of the Fund’s governance because they see it as failing to recognise their increasing importance in the world economy” (Truman, 2015).

As a result, China increasingly demands governance reforms. As Japan in the late 1980s and emerging markets in the 2000s, China points that failing to adjust the governance of international organizations to reflect the growing importance of rising economies will result in a legitimacy crisis. This was clearly stated in Xi Jinping’s speech in Davos in 2017. “The global economic landscape has changed profoundly in the past few decades. However, the global governance system has not embraced those new changes and is therefore inadequate in terms of representation and inclusiveness” adding “we should develop a model of fair and equitable governance in keeping with the trend of time. […] There is a growing call from the international community for reforming the global governance system, which is a pressing task for us”.

When China feels that governance reforms are not forthcoming, it creates new institutions competing with existing ones. “For years China sought a larger role in the Asian Development Bank, but the United States resisted. As a result, in 2015, Beijing created its own multilateral financial institution, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (which Washington opposed, fruitlessly)” (Zakaria, 2020). China also instigated the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and the New Development Bank. Moreover, De Gregorio et al. (2018) argue that the swap agreements extended by the People’s Bank of China in the aftermath of the GFC[1] will “provide a safety net that rivals the IMF.”

However, China is prudent. Despite its frustration, China is mindful that the international architecture remains essential to its development and that it is not (yet) in a position to lead a reform of the world order. “The Western-centered world order dominated by the U.S. has made great contributions to human progress and economic growth. But those contributions lie in the past. [The order] is failing to adjust […] We are dissatisfied and ready to criticize. Yet we are not yet ready to propose a new design.” (Fu Yin, chairwoman of the foreign affairs committee of China’s National People’s Congress, 2016)

[1] See Denbee et al. (2016).

3. Adjusting to Rising Powers: The Case of the IMF

Against this background, we can now examine how the IMF can cope with China’s rise. The core issue is that “the emergence of China will continue to challenge the world financial order. If its growth rate remains high, China will be entitled to claim the largest IMF quota […]. One question is whether this claim will be granted. Another is what China will do with that power” (De Gregorio, 2018).

This article focuses on the first question as it is of immediate relevance. To answer it, we need to look at the IMF governance and understand why China can expect, if not the largest IMF quota (which is still a question for the future), a much larger quota share (which is overdue). Then, we will look for insights from past experience. Specifically, we will look at the response of the IMF to Japan’s rise in the 1980s and to the decision to shift some voting power from advanced economies to rising EMs in the 2000s. Finally, we will examine the case of the 15th General Review of Quotas (hereafter “Review”) concluded in February 2020 without quota share realignment.

3.1. The IMF’s Governance Framework: Quotas, Voting Power, and Legitimacy.

The cornerstone of IMF governance is the quota system. Quotas determine the financial contribution a member is obliged to provide to the institution, the maximum amount of financing a member can obtain from the IMF under normal access, and the distribution of SDR allocations. Importantly, quotas also determine each member’s voting power.

For most of the Fund history, quotas accounted for the bulk of IMF resources (Denbee et al., 2016). To cope with the sharp increase in demand for financial support during the GFC, the IMF supplemented quota resources with borrowed resources (the NAB and the Bilateral Borrowing Agreements – BBAs). As a result, the share of quotas in total resources plummeted. This was viewed as a temporary situation pending a quota increase. With the quota increase agreed under the 14th Review, the share of quotas in total resources bounced back but that was insufficient to restore the primacy of quotas: they only account for slightly less than half of Fund resources. As a result, voting powers which are calculated on the sole basis of quotas are disconnected to total financial contributions.

An important corollary to the principle of a quota-based institution, is that quotas are reviewed periodically to ensure that the Fund has adequate resources and that the quota distribution among members reflects their relative position in the world economy. Failure to adjust quotas in a timely fashion denies an adequate representation of rising power’s views and interests and maintains the influence of a few advanced economies.

3.2. The 9th Review: Dealing with Japan’s Rise

The U.S. response to Japan’s rise in the 1980s is very similar to today’s response to China’s rise. Firstly, the trade tensions. As China today, Japan was seen by U.S. policy makers as implementing unfair trade practices, restricting the access to its markets, and maintaining a regulatory bias favoring local firms. Concerns about the bilateral trade deficit resulted in protectionist measures such as “voluntary export restraints” limiting Japanese exports to the U.S. By the early 1990’s, “something closely resembling a trade war was clearly underway” (Huntington, 1996). Secondly, as today, trade tensions reflected a declinist anxiety in the U.S. Bhagwati (1993) argued that the “political success [of declinism…] adds a lethal edge to the prospect that U.S. leadership will be sacrificed to the myopic and self-indulgent pursuit of “what’s in it for us” economic policies in the world arena.”

This shows that U.S. aggressive and unilateralist approach of international issues is not unprecedented. It has, however, reached new heights. Tensions with Japan did not prevent the conclusion of the Uruguay Round and the birth of the WTO nor an increased influence of Japan in the IMF. In contrast, tensions with China are accompanied by decisions that paralyze the WTO and, as discussed below, block an increased influence of China in the IMF. As “America First” is not new nor an anomaly, the U.S. attitude toward the international system and toward China is unlikely to end with the Trump administration (Cohen, 2019; Zakaria, 2020).

The 1980s wave of declinism was reinforced by a growing East Asian assertiveness. As “successful economic development generates self-confidence and assertiveness” (Huntington, 1996), Asian countries requested increased recognition and a greater representation in international institutions.

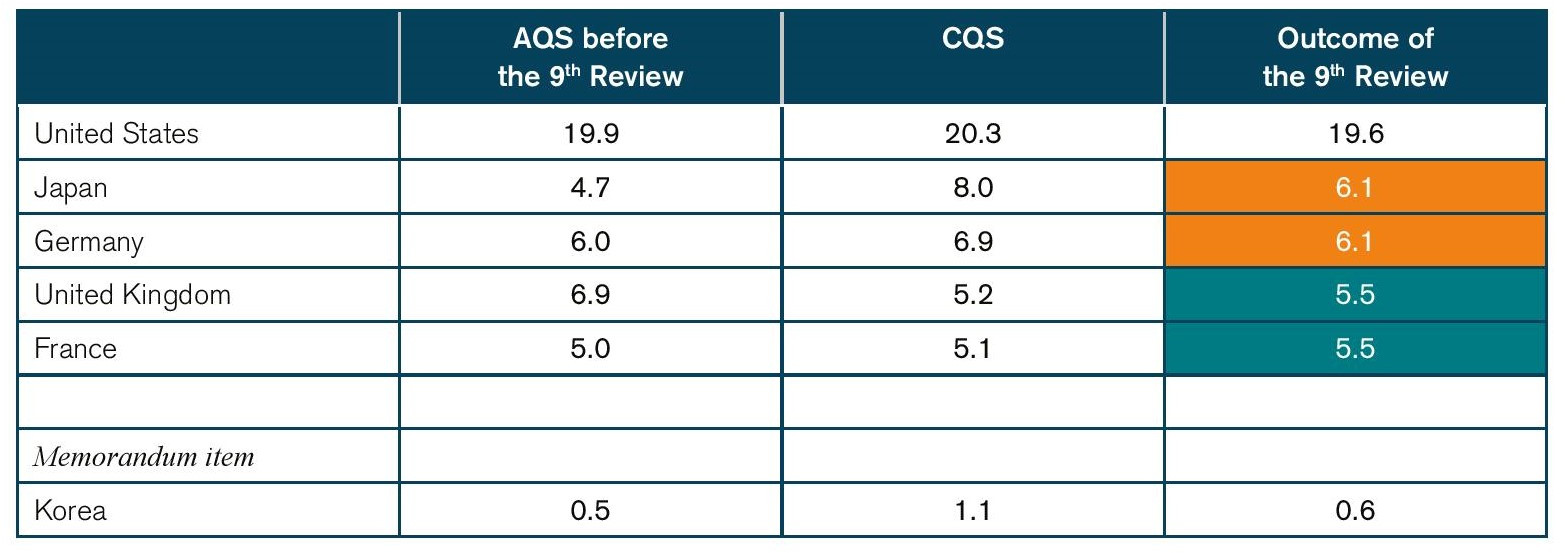

Table 1. Quota shares of the 5 largest shareholders before and after the 9th Review (in Percent)

Source: IMF and Author calculation.

In the IMF, this took the form of a request by Japan and Korea for a larger quota share and voting power. Japan was significantly underrepresented as its economic rise had not been matched by commensurate changes in its quota share. Its “out-of-lineness” (OOL), which is the difference between an IMF member’s actual quota share (AQS) and the quota share calculated using the formula endorsed by the Executive Board (Calculated Quota Share or CQS) was growing rapidly.[1] On the eve of the 9th Review, Japan’s underrepresentation had reached 3.3 percentage points. Korea’s underrepresentation was more limited at 0.6 percentage points (Table 1 and Figure 1).

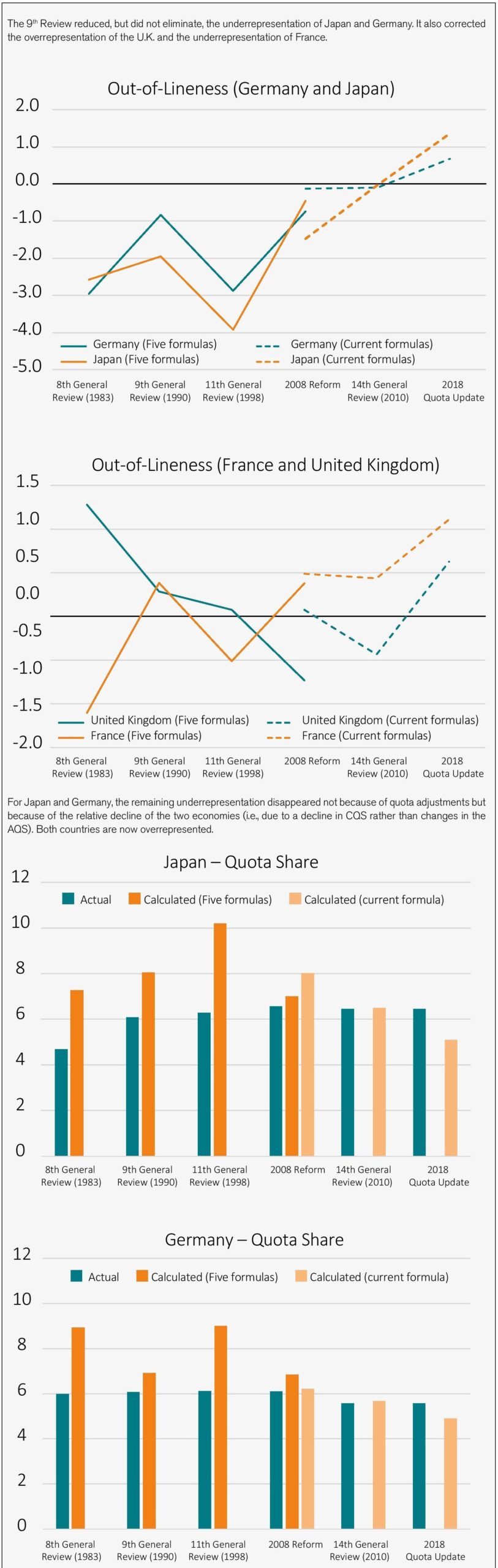

Figure 1. Impact of the 9th Review on Out-of-Lineness (in percentage points)

Source: IMF and author calculations.

Difference between the AQS resulting from a Review and the CQS used for the same Review. The calculated shares use the 5 formulas approach (8th Review to the 2008 Reform), and, since the 2008, the current formula.

Early in the 9th Review, the Japanese Executive Director argued that the distribution of Fund quotas was “clearly inconsistent with world economic realities” and asked an increase in Japan’s quota share. This request was well received because “Japan had begun to play a substantial role as a Fund creditor and provider of official development assistance, which gave the authorities a strong bargaining position. In April 1989, the Interim Committee implicitly acknowledged the point by agreeing that ‘the size and distribution of any quota increase should take into account changes in … members’ relative positions in the world economy’ since the previous Review” (Boughton, 2001).

Though well received, Japan’s request raised political difficulties. The CQS suggested that eliminating Japan’s underrepresentation would make it the second largest shareholder (Table 1). As it was agreed to protect the quota share of developing countries, increasing Japan’s quota share meant that the adjustment burden was concentrated on other advanced economies. The prime candidate for such an adjustment was the U.K. who was overrepresented while the four other largest shareholders were underrepresented (Table 1). In December 1989, the British Executive Director announced that the U.K. was prepared to accept a reduced increase in quota to protect developing countries from the dilution resulting from the ad hoc increase in Japan’s quota. As a result, the U.K. would bear half of the adjustment burden of Japan’s quota share increase but would leave the other half to be distributed among other advanced economies. In other words, the U.K. proposal did not prevent a change in the ranking of the largest members and led to “an acrimonious and very public fight” (Boughton, 2001) between France and the U.K.

The Executive Board agreed, in January 1990, that the issue would be discussed within the G7. In May 1990, the G7 countries found a compromise: Japan would have the same quota share as Germany while France and the U.K. will have the same quota share avoiding France to fall in fifth position (Table 1). While the Germany-Japan parity was short lived, the U.K.-France parity is still effective today.[2] This compromise was endorsed by the IMF Executive Board and allowed a successful completion of the Review.

The 9th Review provides lessons for addressing China’s underrepresentation:

- First, it would be a political compromise. Overrepresented shareholders would have to accept a decline in their quota share and voting power. In particular, Japan would have to accept losing to China its place of second largest IMF shareholder as well as its, symbolically important, place of largest Asian shareholder. Political considerations are large in a review as illustrated by the fate of Korea’s request for an ad hoc increase in quota. Many Directors initially received favorably Korea’s request for a quota share increase but eventually it did not muster enough support. Iran had also requested an ad hoc increase and “creditors who sympathized with Korea found it difficult to support that request without taking the politically awkward step of supporting Iran as well” (Boughton, 2001). Korea will have to wait the 2000s to see its underrepresentation addressed (Figure 2).

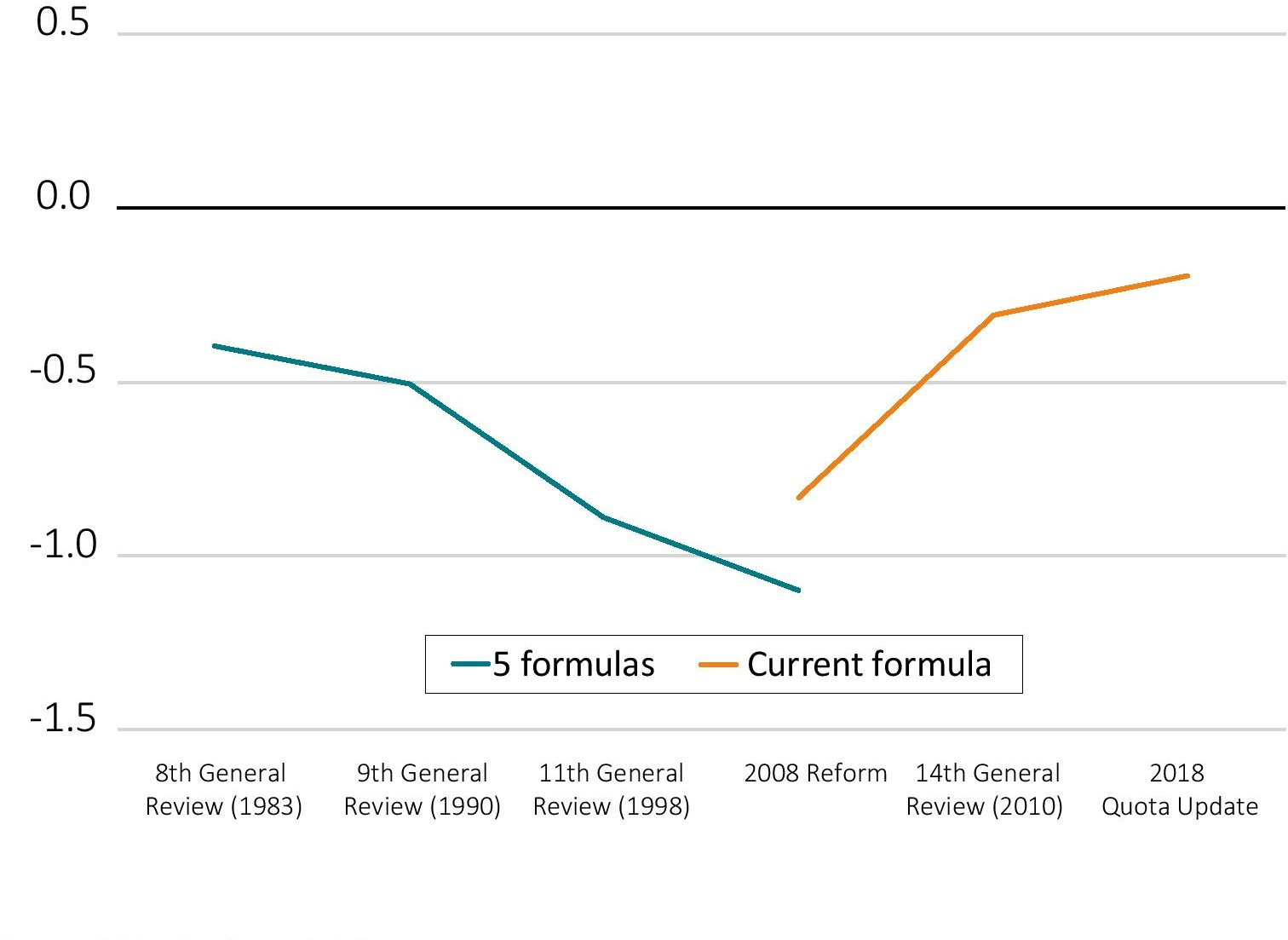

Figure 2. Korea’s Out-of-Lineness (In percentage points)

Source: IMF and author calculations.

- Second, as China’s underrepresentation is massive, it can only be eliminated by a succession of partial adjustments. Japan’s underrepresentation was not eliminated in the 9th Review but only reduced (Table 1). As the weight of Japan in the global economy continued to grow, Japan’s OOL was larger by the time of the 11th Review than it was on the eve of the 9th Eventually, Japan’s and Germany’s underrepresentation disappeared but this was not the result of quota adjustments but rather the result of the decline of their relative position in the world economy driving a reduction CQS (Figure 1).

3.3. The “Quota and Voice” Reform and the 14th Review: Coping with a Legitimacy Crisis and getting the buy-in from Emerging Markets

In the aftermath of the Asian crisis, the GFSN changed considerably (Denbee et al., 2016; De Gregorio et al., 2018). Several EMs started accumulating large foreign exchange reserves as an insurance from having to call on the IMF in case of crisis. They also attempted to develop regional alternatives to the IMF. This forced the Fund to reconsider its role and policies, while engaging in a governance reform to address an acute legitimacy crisis. Three quotations illustrate on the prevailing mood:

First, a sense of urgency: If the mission of the Fund is not examined and the institution revitalised, it could slip into obscurity (King, Governor of the Bank of England, 2006).

Second, governance is part of the legitimacy and credibility problem: If the Asian crisis and its aftermath precipitated the current legitimacy crisis, they combined with a […] longer-term trend that had been undermining its legitimacy for some time: the problem of the Fund’s own increasingly inequitable governance (Best, 2007).

Third, governance reform is part of the answer: One issue on which I agree strongly […] is the need for a change in IMF voting shares and representation. The Fund’s ability to persuade our members to adopt wise policies depends not only on the quality of our analysis but also on the Fund’s perceived legitimacy. And our legitimacy suffers if we do not adequately represent countries of growing economic importance (de Rato, Managing Director of the IMF, 2005).

The Quota and Voice reform was the IMF response. It followed a well-known approach: “By far the most sensible policy for leading powers in dealing with rising powers ought to be efforts to moderate their challenge by incorporating them into the system if they are outside it, or, if they are inside, to provide more symbolic and material benefits to reconcile them to the status quo. Historically, this is how European great powers responded to the rise of Sweden, Russia, Prussia, Germany, Japan and Italy. From the 1960s on it was a key component of the Western response to the Soviet Union.” (Lebow and Valentino, 2009).

As the overrepresentation of advanced countries was at the core of the legitimacy crisis, shifting some voting power from advanced economies to rising EMs was perceived as an adequate reform. This was supported by the U.S. as a way to get more buy-in in the institution by Asian countries and to increase their contribution to Fund resources at a time the U.S. was reluctant to increase its own exposure (Truman, 2014; Lesage et al. 2015). However, the U.S. support for the shift was conditional on maintaining U.S. veto power, which meant that the increase in EMs voting share was to come mostly at the expense of advanced European countries.

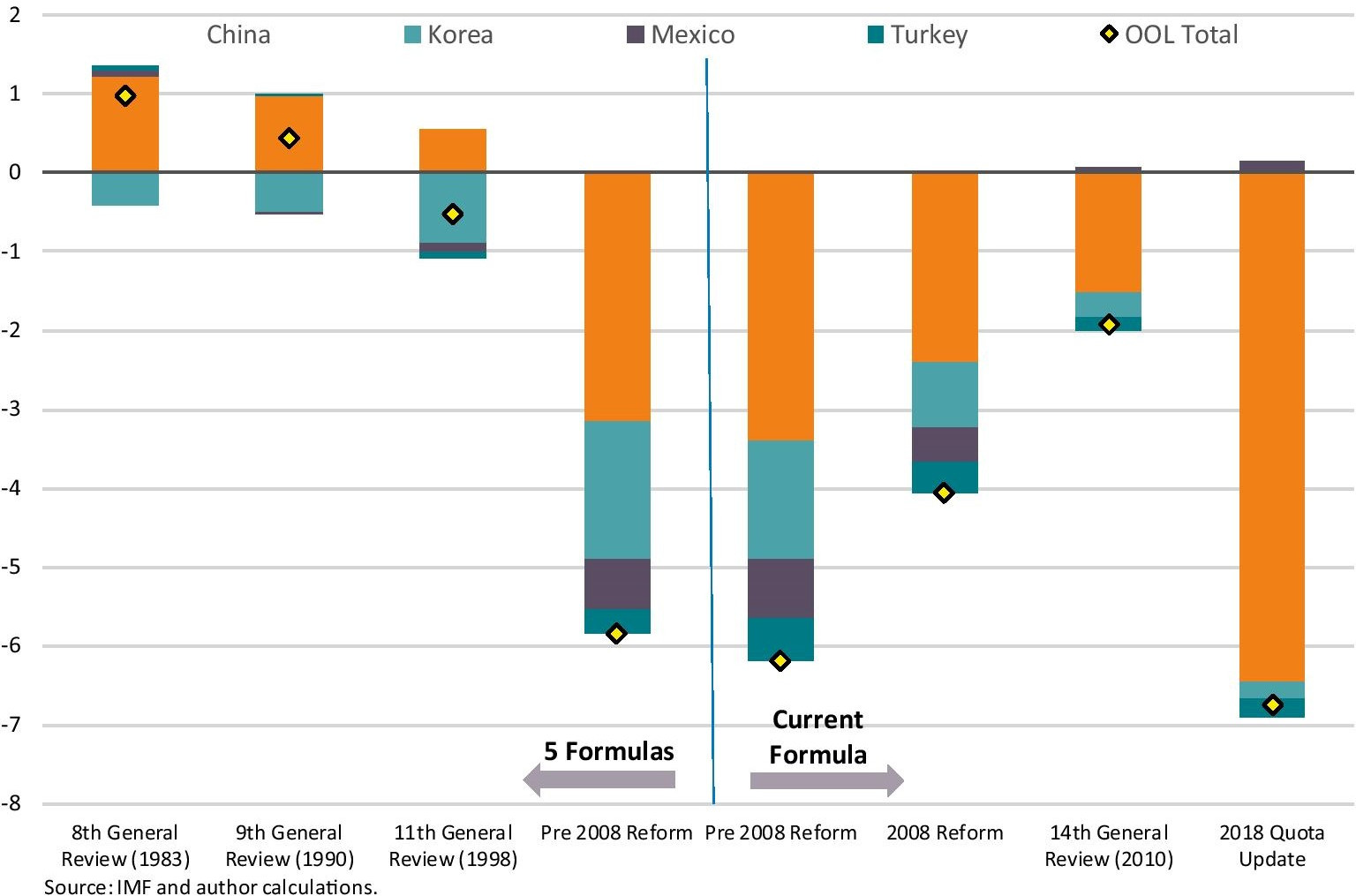

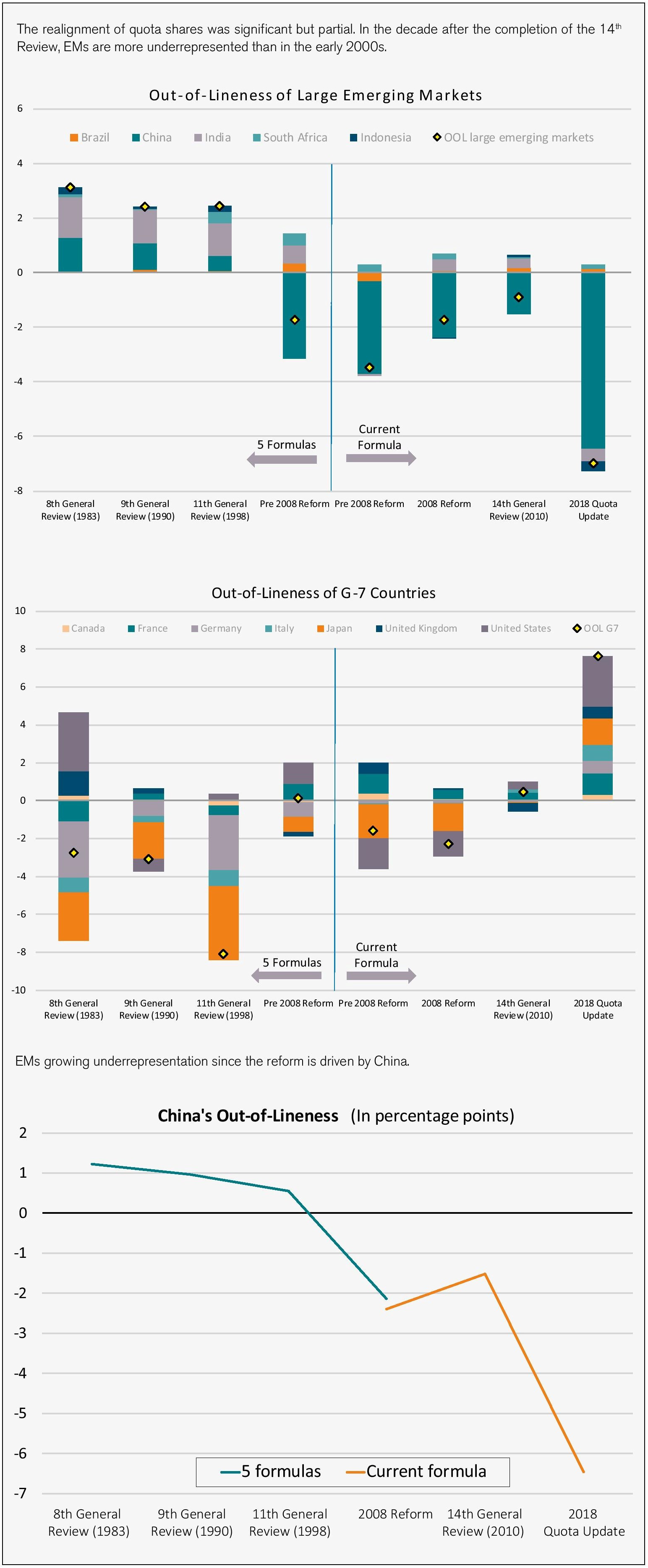

EMs’ voting shares were increased in two phases. In 2008, overall quotas where increased by 1.8 percent to allow an increase in the quota of four highly underrepresented members: China, Korea, Mexico, and Turkey. The quota share of other members was uniformly reduced. Then, in 2010, an additional shift of quota shares to 54 “emerging market and developing countries” (including the four countries who benefited from the 2008 adjustment) took place. Altogether, this reduced by 2/3 the combined underrepresentation of the four most underrepresented members (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Out-of-Lineness of the 4 Largely Underrepresented Countries in the mid-2000s (In percentage points)

This redistribution of quotas and voting power was accompanied by other governance reforms. The representation of the smallest members was improved by a tripling of the “basic votes.” Basic votes, which were set in absolute terms at the creation of the IMF, had seen their voting power eroded over time by the successive quota increases. The reform sets the basic vote at 5.5 percent of total vote preventing an erosion in the future.[3] The second governance reform was related to the functioning of the Executive Board. Its principal element was a reduction (still incomplete) of advanced European chairs to increase the representation of non-advanced countries.[4]

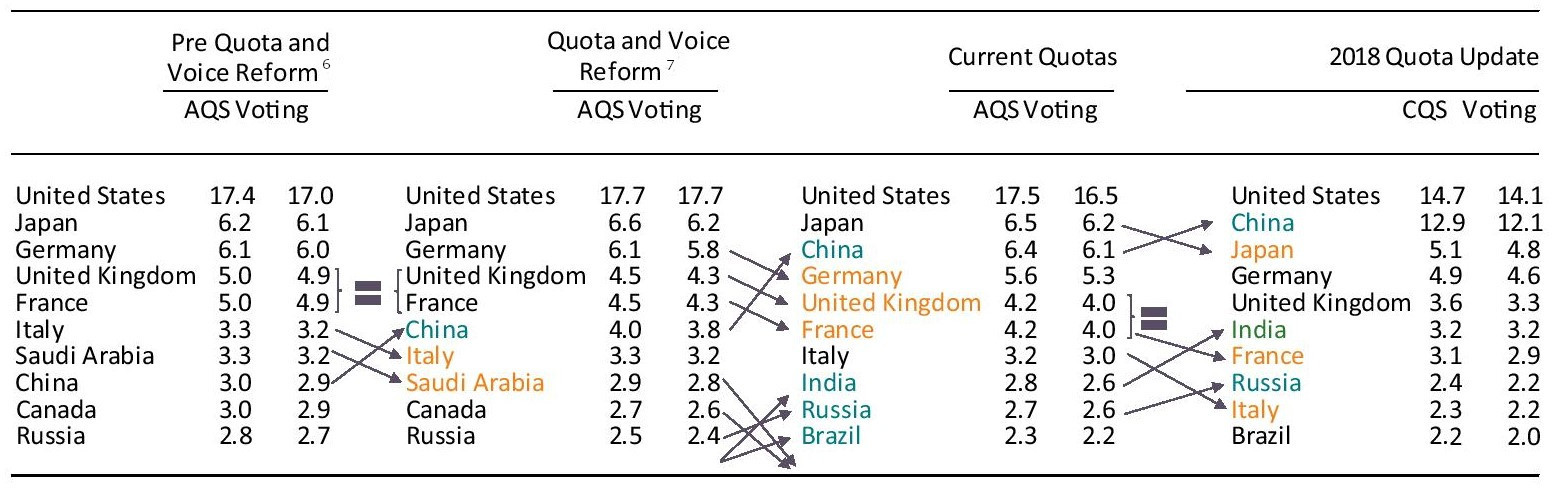

Table 2 summarizes the impact of the Quota and Voice reform and of the 14th Review. It shows that:

- The U.S. quota share remained stable at about 17 ½ percent. In other words, the shift in quota shares from advanced economies to EMs did not come at the expense of the U.S. Nonetheless, due to the change in basic votes, the U.S. voting share declined by half a percentage point but, at 16.5 remains large enough to give the U.S. a veto power on the most important decisions. According to the quota formula, the U.S. is overrepresented. Its CQS is almost 3 percentage points lower than its current quota share and is below the threshold necessary to maintain a veto power. In this context, it is no surprise that the U.S. pushes for changes in the quota formula that would increase its CQS. Sobel, a former Deputy Assistant Secretary at the U.S. Treasury and former U.S. Executive Director at IMF, argues that the weight of the GDP in the quota formula should be increased. The U.S. “GDP share is over 20 percent of the world economy and much higher than its quota share; the U.S. calculated share is two-thirds its GDP share; this points to extreme underrepresentation” (Sobel, 2018). Pointing that “European countries have much lower GDP shares than actual quota shares [and …] Europe is highly overrepresented in the Fund’s voting power” he also argues that the correction of China’s underrepresentation should come at the expense of the Europeans.[5]

Table 2. Ranking of countries according to their quota and voting shares (in percent)

Source: IMF.

- European countries paid most of the price of the Quota and Voice reform with a decline in their quota and voting shares and a reduction of the number of European chairs at the Executive Board. Germany, the U.K., France, and Italy all experienced a decline in their quota and voting shares. Nonetheless, they remain overrepresented. Their combined quota share is about 2.2 percentage points lower than before the Quota and Voice Reform and their voting share by 2.7 percentage points lower, but both remain about 3.3 percentage points above what the quota formula implies.

- By design, EMs’ quota and voting shares increased, and their underrepresentation was significantly reduced (Figure 4). Before the reform, China was the only EM among the 10 largest IMF shareholders. It is now joined by India, Brazil, and Russia. The realignment did not fully correct the underrepresentation of China. One of the reasons for this partial correction was that it would have been unacceptable for Japan to see China becoming the largest Asian member of the IMF (Lesage et al., 2015). Currently, Japan’s quota and voting shares are a mere 0.1 percentage point above China’s.

Figure 4. Out-of-Lineness in the aftermath of the Quota and Voice Reform and the 14th Review (in percentage points)

Source: IMF and Author calculations.

Though impressive by historical standards, the realignment of quota shares was partial (Figure 2) leaving a sense of “unfinished agenda” (Truman, 2009). EMs pushed for further governance reforms highlighting that they were crucial for the legitimacy and the credibility of the institution (e.g., Mohan and Kapur, 2015) and it was agreed to review the quota formula by 2013, bring forward the 15th Review from January 2016 to January 2014 to continue the governance reform and the realignment of quotas (Truman, 2013).

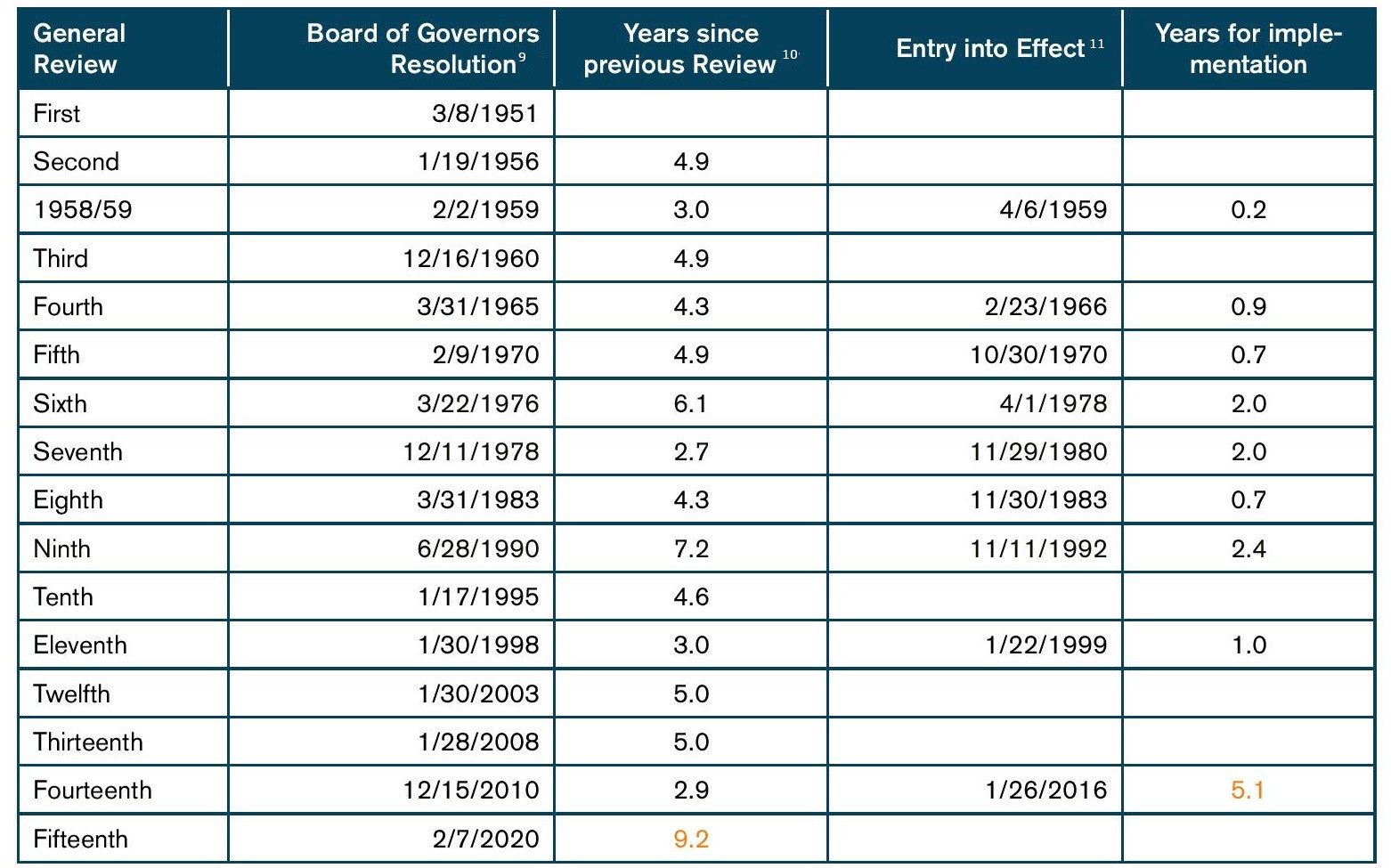

Eventually, the review of the quota formula did not allow to reach an agreement on a new formula (IMF, 2013), which remains part of the governance reform agenda (IMFC, 2019; IMF, 2020b);[8] the 14th Review, concluded on December 2010 entered into force only in January 2016 (the longest implementation delay in history due to the slow approval process by the U.S. Congress, Table 3); and the 15th Review, the longest in history, was not concluded in 2014, but in 2020 (IMF, 2020b) and without any agreement for a quota increase, a quota realignment, or the expected governance reforms.

Table 3. Timeline of the General Reviews of Quotas

Source: IMF and author calculation.

3.4. The 15th Review: From buy-in to Containment

In February 2020, the IMF’s Board of Governor completed the 15th Review without quota increase (IMF, 2020b). Though the U.S. refusal to support a quota increase (Malpass, 2018) was the proximate reason for this outcome,[12] “European and Japanese representatives couldn’t be happier. Behind the scenes, they will break out into dance over keeping their overweight voting power. Japan will remain above China in the Fund’s pecking order” (Sobel, 2019a).

The failure of the 15th Review can be interpreted as a reversal in U.S. policies. The U.S. moved from seeking buy-in from large EMs to containing China. Containing China (i.e., preventing a realignment of voting powers that would benefit China – Figure 4) could only be achieved by blocking an increase in quotas. The U.S. objection to a quota increase was officially based on the assessment that the IMF does not need additional resources: “We are opposed to changes in quotas given that the IMF has ample resources to achieve its mission, countries have considerable alternative resources to draw upon in the event of a crisis, and the post-crisis financial reforms have helped strengthen the overall resiliency of the international monetary system” (Malpass, 2018).[13] But a quota increase does not necessarily mean an increase in resources as it could be (and was planned to be) offset by a reduction in borrowed resources. Then, what was the main reason for the U.S. opposition to a quota increase? It could not be the fear of losing its veto power as a quota increase can be designed to avoid that outcome. It does not appear to be the Trump administration distrust of international cooperation and international organizations nor the refusal to see the U.S. contribution to the Fund increase. Indeed, the U.S. supported extending the recourse to borrowed resources to maintain the Fund lending capacity in a way that increases U.S. exposure … but doesn’t change the distribution of voting powers. The only possible explanation left is that a quota increase was opposed to avoid an increase in China’s quota share.[14]

The failure of the 15th Review is likely to have serious and long-lasting implications for the funding and the legitimacy of the IMF as:

- Governance reforms are further delayed. Beyond the absence of a change in voting shares, the failure to increase quotas delays governance reforms expected since the conclusion of the 14th Review in 2010.

- Quotas will not be adjusted before several years resulting in a growing disconnect between the evolution of the world economy and members’ representation. The Board of Governors left the issue of an increase in and realignment of quotas to the 16th Review, which is targeted to be completed by no later than December 15, 2023 (IMF, 2020b). Assuming that an agreement can be reached so early, past experience suggests that it is likely to take several years to become effective (Table 3).[15] Until then quotas and voting shares will reflect an agreement reached in 2010. In the meantime, China’s underrepresentation, which is already significant and larger than before the Quota and Voice reform (Figure 4; IMF, 2018b), is likely to have grown. Such a massive underrepresentation will be extremely difficult to correct.

- The IMF will continue to rely on borrowed resources for the foreseeable future. With no quota increase and access to borrowed resources set to end between end-2019 (BBAs) and end-2022 (NAB), the IMF lending capacity was at risk of being reduced by half. Considerable efforts were deployed to prevent such an outcome. As the U.S. and a few other members saw the IMF as adequately funded, these efforts aimed at maintaining, not increasing, the lending capacity of the institution. As a first step, the access to BBAs were extended from end-2019 to end-2020. Then, in early 2020, the Executive Board approved the doubling of the NAB size (IMF, 2020a) a new round of BBAs (IMF, 2020c) about half the size of the previous BBAs.[16] This maintains Fund resources until the mid-2020s when a quota increase is expected to enter into force. Nonetheless, despite repeated claims to the contrary,[17] it is increasingly difficult to see the (protracted) recourse to borrowed resources as temporary and as a bridge between quota increases.

[1] The quota formula has changed over time. It is not binding but informs discussions on distribution of quotas shares. For details, see IMF (2018a). For the latest CQS, see IMF (2018b).

[2] France and the U.K also have the same share in the NAB.

[3] As a result of basic votes, voting shares are (usually only slightly) different from quota shares. See https://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/members.aspx.

[4] For more details, see IMF (2010).

[5] China’s quota share (6.4 percent) is lower than suggested by the formula (12.9 percent) and its share in global GDP (15.0 percent).

[6] India is the 13th largest shareholder and Brazil the 20th.

[7] India is the 11th largest shareholder and Brazil the 14th.

[8] Cooper and Truman (2007) and Virmani (2012) discuss the importance of the formula for IMF governance.

[9] The date of the resolution marks the completion of the Reviews.

[10] Time between resolutions

[11] When no quota increase was decided, the cells are empty.

[12] As a quota increase must be approved by at least 85 percent of the voting shares, the U.S. support is necessary.

[13] Historically, the GFSN consists of countries’ foreign exchange reserves with the IMF playing the role of a backstop. New elements have recently been added such as the swap lines between central banks and regional financial arrangements. The U.S. sees in these developments a reason for a reduced role of the IMF. There is no consensus on this, notably because the strength of many of these new elements remain to be tested and they do not have a universal coverage leaving many countries outside of their network.

[14] See also Sobel (2019b) on the importance of China’s voting power for the U.S. position.

[15] For many countries, a quota increase requires Parliament approval, which may take time.

[16] As the U.S. is a NAB participant but has no BBA, its total exposure to the IMF will increase.

[17] For example, during the annual meetings of October 2019, the IMF membership endorsed the recourse to borrowed resources to maintain the IMF’s resources in the absence of a quota increase under the 15th Review restating nonetheless that “We reaffirm our commitment to a strong, quota-based, and adequately resourced IMF to preserve its role at the center of the global financial safety net” (IMFC, 2019).

4. Conclusion

The U.S.-China tensions are not new. They emerged in the early-1990s but were muted by the Asian crisis and the strong U.S. growth in the 1990s. They were revived by the GFC, which rekindled a U.S. declinist anxiety at a time when China became more assertive.

However, U.S.-China tensions have become so intense that they may jeopardize the world order and, as a result, the international organizations that support it. The U.S. has become convinced that international organizations serve better the interests of China than its own. Thus, the Trump administration abandons the U.S. leadership in global governance and cooperation. Instead, it tries to contain unilaterally a perceived threat to its predominance. This policy may push China to conclude that its interests would be better served by creating new institutions than by reforming existing ones.

The case of the IMF illustrates this danger. In the past, and despite political difficulties, IMF members managed to increase the representation of rising powers. This has dramatically changed. The U.S. blocked an increase in quotas in the 15th Review and, as a result, the possibility of a realignment in the relative voting powers that would have increased China’s influence. At the same time, a reform of the NAB extends the scope of its (and Japan’s) veto power to the use of BBA resources (to which China contributes but not the U.S.) in time of crisis. Several NAB participants expressed “misgivings” about “the appropriateness of giving NAB participants the ability to block bilateral borrowing” but agreed to this amendment to “reach closure on the NAB reform” (IMF, 2020a). In that sense, the U.S. remains the country that sets the rules of the games i.e., it remains an hegemon. But it is a fragile hegemon; an hegemon that does not convince but imposes its views. With the failure of the 15th Review to increase quotas, other long-standing governance reforms were also delayed. Thus, the IMF risks facing a new legitimacy and credibility, despite the repeated commitments that “the delay in further quota and governance reforms should be only temporary” (IMF, 2020b).

References

Best, J. (2007). “Legitimacy dilemmas: the IMF’s pursuit of country ownership,” Third World Quarterly, vol. 28(3), pp. 469-488, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01436590701192231.

Bhagwati, J. (1993). “The Diminished Giant Syndrome – How Declinism Drives Trade Policy,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 72(2), pp. 22-26.

Boughton, J.(2001). Silent Revolution – The International Monetary Fund 1979-1989, Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 1111 p., http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2001/index.htm.

Cohen, E. A. (2019). “America’s Long Goodbye – The Real Crisis of the Trump Era.” Foreign Affairs, vol. 98(1), pp. 138-146.

Cooper, R. N., & Truman, E. M. (2007). The IMF Quota Formula: Linchpin of Fund Reform, Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 07-1, 19 p., https://piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/imf-quota-formula-linchpin-fund-reform.

De Gregorio, J., Eichengreen, B., Ito, T., & Wyplosz, C. (2018). IMF Reform: The Unfinished Agenda. Geneva and London: ICMB and CEPR, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 20, 64 p., https://voxeu.org/content/imf-reform-unfinished-agenda.

de Rato, R. (2005). The IMF View on IMF Reform Speech presented at the Conference on IMF Reform, September 23, Washington, D.C. Institute for International Economics, https://www.piie.com/commentary/speeches-papers/imf-view-imf-reform.

Dempsey, M. (2016). “A Conversation with Martin Dempsey,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 95(5), pp. 2-9.

Denbee, E., Jung, C., & Paternò, F. (2016). Stitching together the global financial safety net. London: Bank of England, Financial Stability Paper No. 36, 33 p.

Fu, Y. (2016). “The US world order is a suit that no longer fits” Financial Times, January 6, https://www.ft.com/content/c09cbcb6-b3cb-11e5-b147-e5e5bba42e51.

Huntington, S. P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 367 p.

International Monetary Fund (2010). IMF Board Approves Far-Reaching Governance Reforms, November 5, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/28/04/53/sonew110510b.

International Monetary Fund (2013). Outcome of the Quota Formula Review – Report of the Executive Board to the Board of Governors, January 30, 4 p., http://www.imf.org/en/publications/policy-papers/issues/2016/12/31/outcome-of-the-quota-formula-review-report-of-the-executive-board-to-the-board-of-governors-pp4730.

International Monetary Fund (2018a). IMF financial Operations, Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 183 p., https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/IMF071/24764-9781484330876/24764-9781484330876/24764-9781484330876.xml?rskey=2XSyRr&result=1.

International Monetary Fund (2018b). Updated IMF Quota Data—July 2018, Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/quotas/2018/0818.htm

International Monetary Fund (2020a). Proposed Decisions to Modify the New Arrangements to Borrow and to Extend the Deadline for a Review of the Borrowing Guidelines. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, Policy Paper 20/006, 59 p., https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2020/02/13/Proposed-Decisions-to-Modify-the-New-Arrangements-to-Borrow-and-to-Extend-the-Deadline-for-a-49048.

International Monetary Fund (2020b). Fifteenth and Sixteenth General Reviews of Quotas—Report of the Executive Board to the Board of Governors. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 5 p., https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/PP/2020/English/PPEA2020007.ashx.

International Monetary Fund (2020c). IMF Executive Board Approves Framework for New Bilateral Borrowing Agreements. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, Press Release 20/123, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/31/pr20123-imf-executive-board-approves-framework-for-new-bilateral-borrowing-agreements.

IMFC (2019). Communiqué of the Fortieth Meeting of the IMFC. Washington D.C.: International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/10/19/communique-of-the-fortieth-meeting-of-the-imfc.

Kennedy, P. (1987). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. New York: Vintage, 677 p.

King, M. (2006). Reform of the International Monetary Fund, Speech by Mr. Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England, at the Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER), New Delhi, 20 February, https://www.bis.org/review/r060222a.pdf.

Lebow, R. N., & Valentino, B. (2009). “Lost in transition: Acritical analysis of power transition theory,” International Relations, vol. 23(3), September, pp. 389–410.

Lesage, D., Debaere, P., Dierckx, S. & Vermeiren, M. (2015). Rising Powers and IMF Governance Reform, Chapter 9 in Dries Lesage and Thijs Van de Graaf (eds.) “Rising Powers and Multilateral Institutions,” London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 153-174.

Malpass, D. (2018). Statement of Under Secretary David Malpass Before the U.S. House Financial Services Subcommittee on Monetary Policy and Trade, December 12, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm572.

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2014). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton, updated edition, 561 p.

Mohan, R., & Kapur, M. (2015). Emerging Powers and Global Governance: Whither the IMF? Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, Working Paper 15/219, 54 p., http://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Emerging-Powers-and-Global-Governance-Whither-the-IMF-43330.

Nye Jr, J. S. (2015). Is the American Century Over? Malden, MA: Polity, 152 p.

O’Sullivan, Michael (2019). The Levelling – What’s Next After Globalisation. New York: Public Affairs, 368 p.

Shambaugh, D. (2013). China Goes Global – The Partial Power. Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 409 p.

Sobel, M. (2018). The United States and IMF Resources, Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic & International Studies, CSIS Brief, 11 p., https://www.csis.org/analysis/united-states-and-imf-resources%E2%80%94-path-forward-0.

Sobel, M. (2019a). US proposal may address IMF resources – Avoiding quota changes postpones voting-power debate, Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, March 28, 2 p., https://www.omfif.org/2019/03/us-proposal-may-revivify-imf-resources/.

Sobel, M. (2019b). US Treasury misguided on IMF quotas, Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, April 24, 1 p., https://www.omfif.org/2019/04/us-treasury-misguided-on-imf-quotas/.

Temin, P. and Vines, D (2013). The Leaderless Economy: Why the World Economic System Fell Apart and How to Fix It. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 328 p.

Truman, E. (2009). IMF Reform: An Unfinished Agenda. VoxEU and PPIIE Op-ed; 7 p., https://piie.com/commentary/op-eds/imf-reform-unfinished-agenda.

Truman, E. (2013). The Congress Should Support IMF Governance Reform to Help Stabilize the World Economy. Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 13-7, 14 p., https://piie.com/sites/default/files/publications/pb/pb13-7.pdf.

Truman, E. (2014). IMF Reform Is Waiting on the United States. Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 14-9, 8 p., https://piie.com/publications/pb/pb14-9.pdf.

Truman, E. (2015). What Next for the IMF? Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 15-1, 10 p., https://www.piie.com/publications/policy-briefs/what-next-imf.

Truman, E. (2017). International Financial Cooperation Benefits the United States. Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics, Policy Brief 17-10, February, 12 p., https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/pb17-10.pdf.

Virmani, A. (2012). Quota formula reform is about IMF Credibility, VoxEu Column, June 22, 3 p., https://voxeu.org/article/quota-formula-reform-about-imf-credibility.

Xi, J. (2017). President Xi’s speech to Davos in full, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/01/full-text-of-xi-jinping-keynote-at-the-world-economic-forum.

Zakaria, F. (2019). “The Self-destruction of American Power: Washington Squandered the Unipolar Moment,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 98(4), pp. 10-16.

Zakaria, F. (2020). “The New China Scare – Why America Shouldn’t Panic About Its Latest Challenger,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 99(1), pp. 52-69.

Zhou, X.(2019). China is Committed to Multilateralism, Project Syndicate, September 4, https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-aiib-multilateral-institutions-cooperation-by-xizhou-zhou-2019-09.