The EU Digital Markets Act: Assessing the Quality of Regulation

Published By: Matthias Bauer Fredrik Erixon Oscar Guinea Erik van der Marel Vanika Sharma

Subjects: Digital Economy European Union

Summary

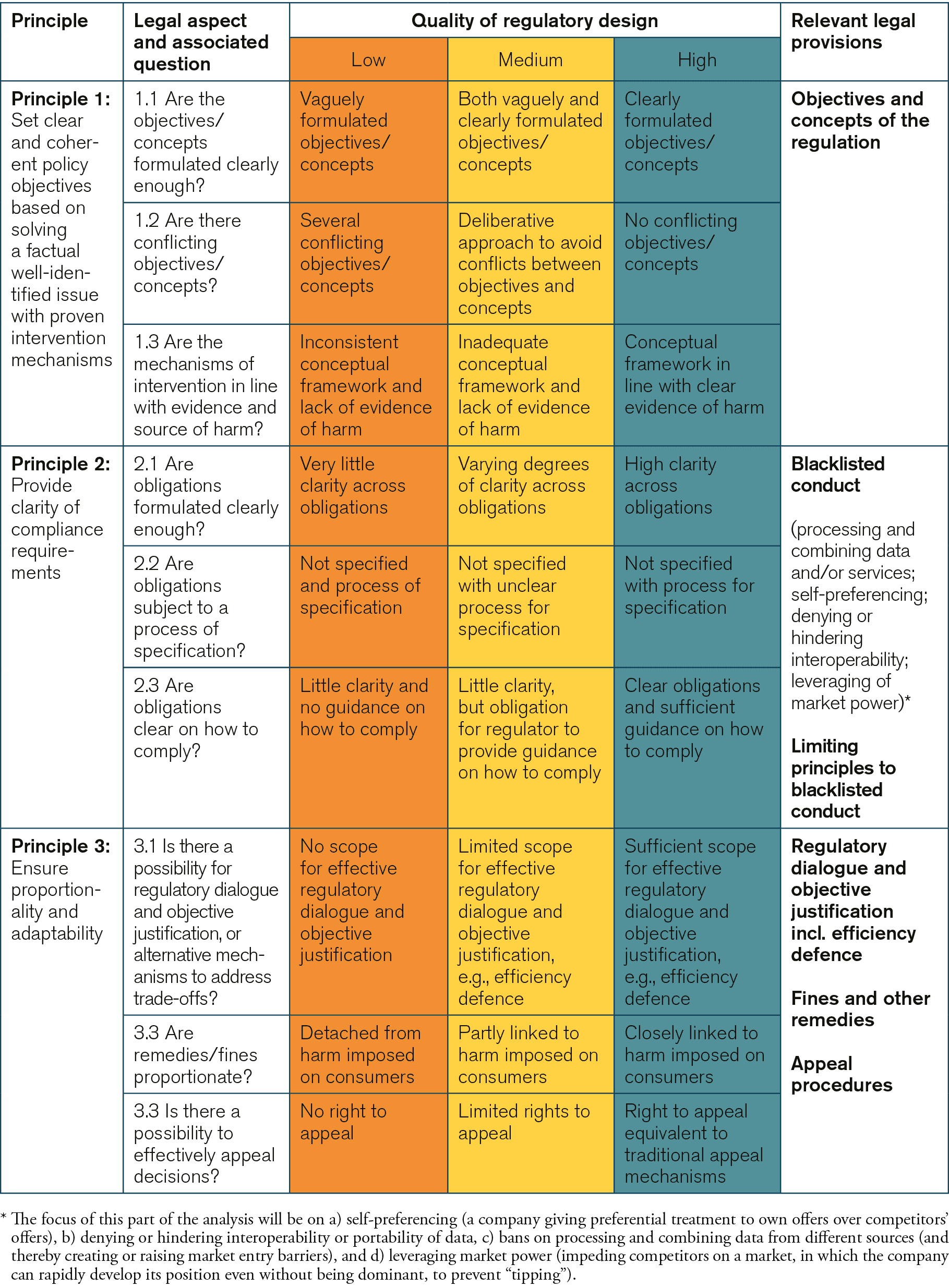

The proposed Digital Markets Act (DMA) is an opportunity to prevent and remedy anti-competitive conduct by large digital platforms. If the Act is designed in an adequate manner to target specific problems, it can improve the contestability of platform services markets and markets that rely substantially on digital services. However, the DMA takes a novel approach to regulation, and novelty in concepts and regulatory requirements can lead to outcomes that later have to be corrected. Fortunately, the EU is not alone in experimenting with new regulations that specifically target the market power of large digital platforms. There is a great scope for policymakers to learn from similar frameworks in Europe and the United States.

In this study, we compare key parts of the DMA proposal with similar legislation implemented or proposed in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States –– in light of established principles for good regulatory design. We analyse the structure and quality of these regulations, not if they go in a certain ideological, political or commercial direction. We find that there are some areas where the EU could learn from other proposals to make the DMA more fit for purpose, and avoid unintended consequences on Europe’s economy.

In its current form, there are several ambiguities in its objectives, concepts, and structure that risk leading to an ineffective regulation and a rising number of legal disputes. Based on the analysis in this study, we recommend the following changes to the DMA:

- The DMA’s objectives should be narrowed. Clarity should be provided on how the regulatory objectives relate to well understood concepts in traditional competition law, particularly competition and contestability. Without a conceptual correspondence to established rules, it becomes even more important that it is clear from the start how market dominance and abuses of market power operate in the DMA.

- A functional definition of regulated “core platform services” would help the regulator to focus the DMA on the distinct problems of these services.

- The designation criteria for gatekeepers should be clarified and extended by additional qualitative parameters coherent with the risk of harm. Inspiration for such a change can be found in Germany’s Act Against Restraints of Competition (“GWB10”) and the UK proposal.

- Obligations put on the platforms should be clarified. Generally, more guidance should be given to companies on how they could comply with the DMA.

- The DMA could provide better opportunities for regulatory dialogue and the right to defence –– helping both the regulator and the regulated platforms to target the problems.

Corresponding author: Dr Matthias Bauer ([email protected]). Dr Bauer is a Senior Economist at ECIPE. Fredrik Erixon is Director at ECIPE. Oscar Guinea, Professor Erik van der Marel, and Vanika Sharma are Senior Economists and Research Assistant, respectively, at ECIPE. ECIPE’s work on Europe’s digital economy receives funding from several firms with an interest in digital regulations, including Amazon, Ericsson, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Rakuten, SAP, and Siemens.

1. Good Regulatory Design – Why it Matters for the DMA

The European Union is about to establish a new Digital Markets Act (DMA) to regulate so-called gatekeeper platforms, i.e. large commercial providers of core platform services such as search engines, online intermediation, and social networking services.[1] The European Commission argues that these gatekeepers “are entrenched in digital markets, leading to significant dependencies of many business users on these gatekeepers, which leads, in certain cases, to unfair behaviour vis-à-vis these business users”.[2] Studies commissioned during the impact assessment of the DMA arrived at the same conclusion: there is, in the language of competition policy, a core “theory of harm” in the DMA.[3]

However, the proposal has drawn criticism. Some voices are calling for more comprehensive measures to reduce the preeminence of large technology companies.[4] These critics are especially concerned with the acquired market dominance of these platforms, and one conclusion is that some companies should receive structural remedies and be subject to much tougher restrictions. Others have raised concerns about the Act’s general direction of travel or drawn attention to specific parts of the regulation that are ambiguous, impractical, or could lead to unintended economic harm in Europe. A particular concern is that very few gatekeepers have a clear understanding of what the DMA specifically asks from them.

In this study, we will provide recommendations on how the DMA can be improved while avoiding unnecessary delays and maintaining an ex-ante regulation that targets market-abusive behaviour that distorts competition and contestability. Moreover, the changes we are proposing aim to strengthen the link between the DMA’s objectives and how it is expected to work in practice. In short, the purpose of the study is to improve the chances of the DMA having a positive impact on competition and markets, and not hindering innovation or slowing down economic modernisation.

A specific regulation for gatekeepers is a novel approach. Since it has not been done before, no one knows how such a regulation will impact on the platforms, their users, and the wider economy. It is therefore important that the DMA and similar regulations start from established principles of good regulations and avoid messy structures and implementation. As with other ex-ante regulations of markets and firms, a benefit of the DMA would be to make it clear what gatekeepers are allowed and not allowed to do –– and not force upon the regulators a policy design that is not fit for modern markets or that raises more questions than it answers. Therefore, our method in this study is to compare the DMA proposal with similar and related initiatives in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States,and how they stand up to established principles of good regulation. Europe is not alone in drafting new regulations for large platforms and their competitive behaviour, and each party can learn from the other.

All new business regulations face similar challenges. For a regulation to be successful, it should be based on clear objectives and go through rigorous scrutiny in impact assessments.[5] However, some regulations face more challenges than others, and this is especially the case for regulations like the DMA that go to the heart of innovation and target complex technology. Regulators are then confronted with matters that are difficult to place in a conventional model of regulation. Moreover, the effect of the regulation can be extraordinarily powerful because it works with frontier technological development and market change. The risk is that a poorly designed regulation will have an outsized negative impact on the economy.[6]

This is why international organisations frequently push governments to improve the quality of regulation. In the past, unclear objectives and inadequate frameworks for implementation have often caused unnecessary economic, social and environmental costs. Therefore, guidelines and principles from organisations like the OECD, the World Bank and the WTO aim to make regulation “fit for purpose”. For instance, the OECD says that “clear objectives and frameworks for implementation” are critical for the efficiency of a regulation. Moreover, it also suggests “drafting and adopting regulation through evidence-based decision-making” and the use of external “mechanisms and institutions to actively provide oversight of regulatory policy procedures and goals”.[7]

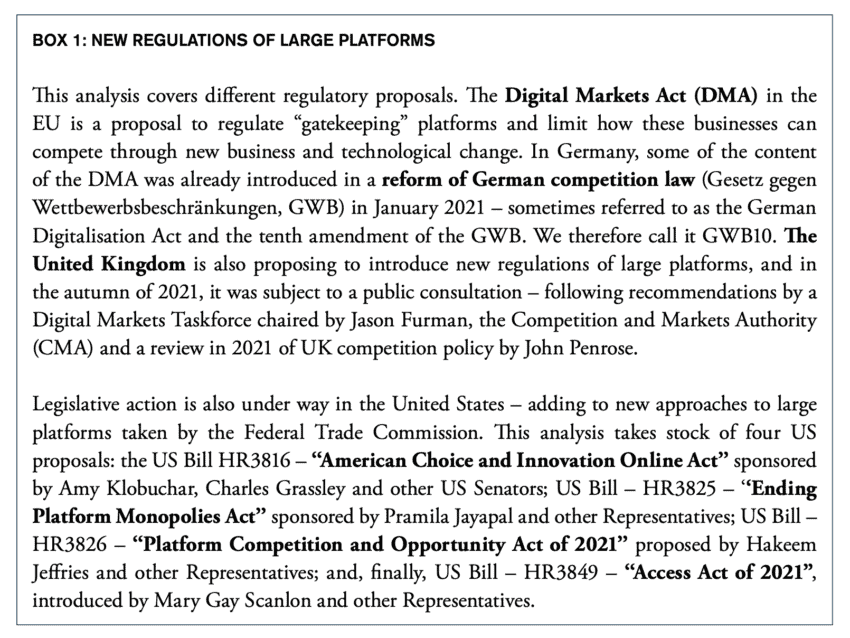

For regulators to better harness the power of innovation, the OECD has set out new principles that better meet the needs of rapid digitalisation. These principles include measures to improve the quality of evidence, regular stakeholder engagement, international regulatory cooperation, and to help innovators navigate regulatory environments. They also stress the importance of outcome-focused measures to enable innovation and opportunities offered by digital technologies and data. A similar set of recommendations have been developed by the World Economic Forum, and they make clear that “adapt and learn mechanisms” are centrally important for regulations to improve and avoid being a source of economic harm.[8] Figure 1 presents several key principles of good regulatory design.

Figure 1: Key principles of good regulations

Source: own assignment based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020).

Source: own assignment based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020).

All three key principles are straightforward. Principle 1 suggests that regulations should be based on clear and consistent policy objectives, and that regulators should ensure that the chosen instruments can achieve these objectives. Such a principle requires a solid understanding of the market conditions, emerging technologies and how a regulation will impact corporate behaviour. Especially, in fast-moving markets with rapid technological change, it is vital that policymakers go for measures that are designed exactly to achieve the objective and do not lead to unintended consequences –– such as a slowdown in technology diffusion.

Principle 2 is equally simple: make sure the regulation is understood and that those exposed to it know how they can comply. However, the importance of this principle is routinely neglected, leading to unintended economic harm. Businesses are generally less likely to adopt or experiment with new technologies and business models if regulations are confusing, and if it is unclear what they mean in practice. It links up with the first principle: having many objectives and requirements in one regulation is often a sure way of creating confusion.

Principle 3 takes us into the realm of smart regulations. Regulators should learn about the consequences of the regulation, have a mechanism for addressing trade-offs, and be prepared to change practice if needed. Adapt and learn mechanisms include having a design that allows for the development of new business models. Such mechanisms also imply having effective mechanisms for regulatory dialogue and judicial review (appeal mechanisms) –– which are especially important in situations when authorities have an incomplete understanding of business models and market conditions.[9]

[1] European Commission (2020a). Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act). 15 December 2020. Henceforth “DMA proposal”

[2] DMA proposal, page 1.

[3] European Commission (2020b).

[4] See, e.g., European Parliament (2021).

[5] In this context, regulation generally refers to the diverse set of instruments by which governments set requirements on companies and citizens (OECD 2021). Regulatory design defines the process by which policymakers, when identifying a policy objective, decide whether to use a regulatory tool, and proceed to draft and implement a regulation through evidence‐based decision-making (OECD 2012a). A large body of regulatory guidelines and recommendations is provided by the OECD and other international organisations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Trade Organisation (WTO 2021). A more recent strand of these organisations’ work addresses novel regulatory challenges and new principles arising from global technological developments and electronic commerce and their implications for competition and innovation. This work was informed by reports from national regulatory authorities and private sector organisations on how new technologies and businesses create value and innovation in digital ecosystems and increasingly digitised economies.

[6] van der Marel et al. (2016) and Ferracane et al. (2020).

[7] OECD (2012a; 2012b)

[8] WEF (2020).

[9] Important lessons can be drawn from traditional network industries. In the past, governments have regulated some industries more than others in terms of entry conditions, services’ characteristics and prices due to perceived (natural) monopolies or the need to correct market failures. Airlines, cable television, banking and insurance, postal services, railroads, telecommunications, and utilities are among the sectors which have been and still are heavily regulated by governments. Governments assumed that in the absence of government intervention, these industries would be characterised by higher prices, poor quality services, costly duplication of networks and inadequate investments in equipment and innovation. This belief – the political defence – was partly cultivated through regulatory capture, i.e. regulators co-opted to serve the commercial, ideological or political interests and therefore were reluctant to contest regulations and experiment with modifications to the original policies. However, in recent years most of these sectors have benefited from substantial regulatory reform to overcome poor services, lack of infrastructure investments and lagging innovation. Deregulation and privatisation increased investments, competition, and innovation, which has had significant positive effects on consumer welfare (see, e.g., OECD 2011).

2. Assessing the Quality of the Digital Markets Act and other Platform Regulations

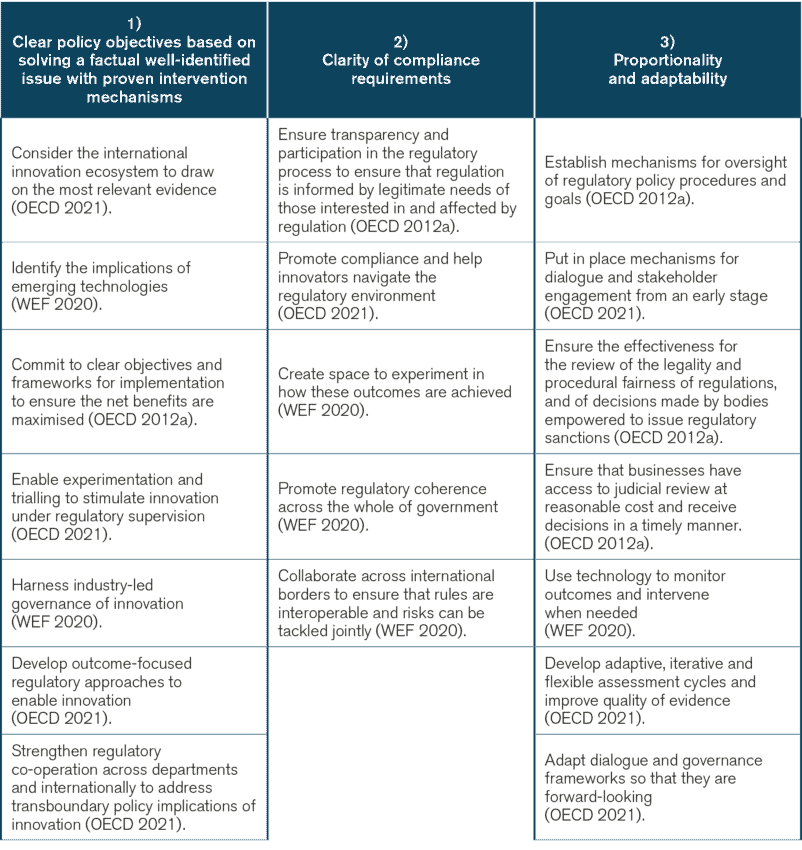

How are these principles of good regulatory design manifested in the DMA and other types of regulations that focus on gatekeepers? In this Section, we will assess the European Commission’s DMA proposal (“DMA proposal”) and the newer rules in Germany, the envisaged rules in the UK and the US. We are guided by the classification of principles outlined in Figure 1. For each law or proposal , we assess the degree of regulatory quality on the basis of the analytical framework outlined in Table 2 below. Chapter three will provide an overview of policy recommendations.

Table 2: Assessing the quality of gatekeeper regulations: a taxonomy

Source: own taxonomy based on OECD (2012a, 2021) and WEF (2020).

2.1. Principle 1: objectives’ clarity coherence, and knowledge of market mechanisms

Regulating digital platforms has required novel policy approaches, which is reflected in the basic design of the examined regulations. There is a great degree of variation between various countries’ legal frameworks, suggesting a level of experimentation with regard to the appropriate level and structure of regulation. Even if all the regulations covered in this study start from similar presumptions, they end up with different results in how they formulate their objectives and the basic concepts in the regulation. Some regulations have more vaguely formulated objectives, others take a more distinct approach.[2]

Clarity and coherence of objectives

The DMA proposal has a multitude of objectives, some of which are anchored in traditional competition policy. The overarching objectives are fairness, competition and contestability, while innovation and consumer protection seem to enjoy a lower priority. While the objective can be associated with the underlying theory of potential harm that has guided the design of the Act, some lack specification. For example, contestability by smaller firms over contestability by platform peers is favoured without a clear justification. Similarly, the US Access Act of 2021, provides objectives that are less clearly defined.

The context and the scope of the regulations are also relevant. For instance, the above-mentioned US Access Act of 2021 is a fairly narrow regulation, when compared with the DMA and other platform regulations that take a broader approach to regulating competition-relevant behaviour of digital platforms. This Act chiefly addresses interoperability and has as its objectives the promotion of competition, the lowering of entry barriers, and the reduction of switching costs for consumers. In other words, its overarching objective is to improve interoperability. The Act Against Restraints of Competition (“GWB10”), which reformed the traditional competition law framework to target digital platforms, also has a distinct set of objectives, albeit broader than the US regulation –– primarily to prevent abusive practices by companies that have market-dominant positions.

While the UK proposal also aims to establish a broad regulatory framework addressing competition problems associated with large platforms, its objectives seem to potentially differ from those of the DMA including its level of integration with traditional competition policy. Like the DMA proposal, its overarching objectives are proposed to be to encourage competition and innovation while ensuring consumer protection. It is similar to the DMA proposal when it comes to the basic concepts of the regulation, especially the designation of gatekeepers. However, the difference is primarily the stronger anchor in objectives and concepts associated with traditional competition policy and acknowledgement that trade-offs in different objectives may occur.[3] In addition, the UK proposal is considering design options that do not rely on self-executing obligations.

Adequate intervention and knowledge of market mechanisms

Scope

The DMA proposal follows an approach that is less rooted in traditional competition policy. For instance, the criteria for designating a platform as a gatekeeper in need of regulation references qualitative dimensions such as having an “entrenched and durable position”. However, the underlying tests for the standard method of designation are based on quantity and size (e.g. the number of users and turnover), taking a more narrow approach than traditional competition-policy concepts such as market dominance and market power. The recitals make an argument that concentration of platform market power and the attendant potential abuse are a consequence of the specific characteristics of the digital economy –– in particular significant scale economies and network effects, the potential degree of vertical integration, and the role of data. These characteristics or their impact are deemed to be general after a given size and do not form part of the designation process and the application of the Act.

By contrast, Germany’s GWB10 goes beyond size thresholds when adopting a presumption of harm and determining the scope of the regulations. GWB10 requires the competition authority to substantiate its claims on the basis of market investigations and, to that effect, lists several criteria that need to be considered for the assessment of market dominance. While the tenth revision of the German competition law has been done to achieve “speed of procedure” and “clarification regarding certain types of conduct” by companies, these objectives need to be put into the perspective of Germany’s general competition policy, which puts an emphasis on evidence-based enforcement.

The US proposals lack clarity in their conceptual definitions of the mechanisms of harm. For example, the “American Choice and Innovation Online Act” proposal provides a list of conduct that is by default considered discriminatory and thus unlawful, e.g. self-preferencing and the denial of interoperability demands. However, the law does not describe the covered practises, making its remit less clear. For example, little guidance is given on what discrimination means in practice, which forms of discrimination are legitimate and which are illegitimate. The proposed US “Ending Platform Monopolies Act” applies a conceptual framework that aims at promoting competition and economic opportunity in digital markets by eliminating the conflicts of interest that arise when a platform owns or controls another platform and certain other businesses. However, neither the scope of competition nor the concept of economic opportunity is defined in this proposal. The proposal also fails to define “nascent competition” and “potential competition” –– two important concepts that are used to motivate the obligations and restrictions and their activation.

The UK government takes a different approach. It links its proposed ex-ante regulation of large platforms with the country’s competition regulation and CMA practices. For instance, the criteria for the Strategic Market Status (“SMS”) designation (the UK equivalent of gatekeeper designation in the DMA) is based on market power and the ability to use market power in a way that constitutes abuse of a dominant position. In order for the regulator to actually issue an order against an SMS-designated platform, it seems that it will need to first conduct a market investigation and find proof for its theory of harm, although there remains some uncertainty as to whether this process will be required.[4]

Remedial action

The DMA is broadly a self-executing regulation, meaning that its obligations are immediately applicable. The reason why it seems to be so, is that the DMA seeks to prohibit behaviour that is under scrutiny in national antitrust cases or has been in other sectors.

By contrast, Germany’s GWB10 does not provide for self-executing obligations. It requires Germany’s competition authority to investigate markets, corporate conduct and its impact. As a consequence, the enforcement of GWB10 is likely to be different compared to the DMA. In addition, the German approach allows for exemptions when platforms improve the production and distribution of goods or support technical and economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefit. In the case of multi-sided markets and networks, when the market position of a company is assessed, the competition authority shall also take account of network effects, economies of scale, data relevant for competition, and innovation-driven competitive pressure. These factors are intended to help identify the problems that motivate GWB10 and design the remedies. The extent to which these factors are a closed list will determine the degree to which different types of evidence can inform the regulatory assessment.

Similar to the DMA proposal, the US proposals by and large entail self-executing obligations and do not require market investigations before intervention. The proposed US “Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021”, for instance, aims at promoting “competition” and “economic opportunity” in digital markets by restricting acquisitions by platforms. Neither the term competition nor economic opportunity is defined in this proposal. Both terms lack clarity about how they relate to observed market characteristics and harm the bill intends to address. The intended prohibition of acquisitions is self-executing and creating a risk of overenforcement. While there is the possibility of an exemption if the acquiring platform can demonstrate by “clear and convincing evidence” that an intended acquisition encourages competition and economic opportunity, it is unclear what proof that could actually lead regulators to approve an acquisition.

The UK proposal has some distinct features. It seems to propose a conceptual framework that makes evidence of anti-competitive effects by large platforms important for the execution of the regulation. The UK proposal appears not to rely on self-executing obligations. Instead, the regulator would aim to enforce requirements on the basis of knowledge of market characteristics and evidence of abusive or anti-competitive practises by large platforms. There are novelties in the proposal that are less associated with a classic ex-post regulation of competition, e.g., the focus on entrenched firms with a strategic market position. However, the proposal suggests that the competition authority needs to ensure a solid evidence base for any market intervention. It is, for example, stressed that the SMS designation should be based on evidence that is relevant for understanding if there is a market problem related to a specific large platform. This framework provides in principle the ability to design remedies that closely map identified concerns on a case by case basis.

2.2. Principle 2: obligations clarity and implementability

Let us now turn to the second principle: the importance of providing clarity about obligations, and how firms should act to comply with the regulation. We focus especially on blacklisted conduct – and limiting principles to blacklisted conduct, i.e. exemptions applied in case of pro-competitive effects, practices complementary to protecting data, and innovation incentives. Due to their coverage in most of the frameworks analysed in this paper, we focus on the conduct listed below and whether the remedial actions they entail are clearly defined:

- self-preferencing (a company giving preferential treatment to own offers over competitors’ offers) and terms of ranking,

- denying or hindering interoperability or portability of data,

- processing and combining data from different sources without user consent (and thereby creating or raising market entry barriers), and

- leveraging market power (impeding competitors on a market, on which the company can rapidly develop its position even without being dominant, to prevent “tipping”).

Clarity of Obligations

The DMA is a hybrid proposal: parts of its obligations are self-executing while others are “susceptible of being further specified” before they are enforced (all Article 6(1) obligations) although the proposal does not provide much clarity on how and when they should be specified. The DMA seeks to regulate certain types of conduct that are – by default – considered “unfair” and “limit contestability”. These measures include conduct related to self-preferencing, the interoperability of data, the processing and combination of data from different sources, and the leveraging of market power to “tip” markets. While Article 5d is fairly straightforward, prohibiting platforms to restrict business users from raising issues with relevant public authorities, other rules lack preciseness. Rules on self-referencing, for example, seem a priori relatively clear, but might raise uncertainty when applied to different business models.[5] Other obligations that are not clear in scope and their precise form include broad rules for the processing and combination of data, measures related to interoperability of ancillary services and switching, and measures imposed on platforms that are not gatekeepers but “risk” developing towards an “entrenched and durable position” in the market that could make them relevant for the DMA. It is not always clear to which products these obligations apply and how broad or narrow they are to be construed. As guidance by case law is missing, gatekeepers would need guidance from the Commission to avoid overenforcement and unintended harm on users.

Germany’s GWB10 similarly lacks some clarity with regard to obligations. With the exception of rules for self-preferencing, which seem to go into more detail than other of the provisions,[6] other obligations (e.g. interoperability requirements, the type of practices that may “directly or indirectly impede competitors”, and practices that “appreciably” raise barriers to market entry by processing data relevant for competition) are less clear. For example, Germany’s competition authority may prohibit “refusing the interoperability of products or services or data portability, or making it more difficult, and in this way impeding competition”. Designated companies may find it challenging to comply with this obligation as the law does not specify the critical conduct, nor does it specify the products and services (messaging, social media interfaces, online storage, online retail) to which the obligation applies and associated interoperability criteria, technical standards or business conduct that may be deemed an impediment to competition.

The proposed “American Choice and Innovation Online Act” also provides little clarity about its obligations.[7] By contrast, the proposed US ‘‘Ending Platform Monopolies Act’’ has clearer obligations.[8] The obligations in the US “Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021” is a mix and there are varying degrees of clarity across its blacklisted conduct. While the obligations are relatively clear with regard to prohibited conduct, the Act lists several exemptions which leave much room for interpretation. Not least because of its narrow focus, the proposed US “Access Act of 2021” gives much more clarity about what its obligations mean. Its main body of obligations is that a covered platform shall maintain a set of transparent, third-party-accessible interfaces to enable the secure transfer of data to a user, or with the affirmative consent of a user, to a business user at the direction of a user, in a structured, commonly used, and machine-readable format that complies with certain standards issued by a “technical committee” at the FTC.

Specificity of obligations and process of specification

Many of the examined regulations rely (partly or greatly) on self-executing requirements applicable to all businesses alike.[9] The rationale for the interventions is provided in the general presumptions that motivate the self-executing frameworks reducing the need for supporting evidence of harm in their enforcement.

Just like the DMA proposal some Article 19a[10] GWB10 obligations are based on preceding cases of competition cases, most of which are still pending. This raises the question as to whether the conduct that is prohibited actually leads to harm. However the GWB10 takes a case-by-case analysis and permits companies under investigation to sufficiently justify their conduct, which may limit the possibility that unharmful conduct is banned.

Similarly, the UK regime seems to be considering other options than self-executing obligations. Rather, companies with SMS designation will be subject to a code of conduct that applies to the “activity (or activities) that led to a firm being designated” as such, also taking a case-by-case approach. The UK government has argued against adding components to the legislation that make specific how principles apply to either specific firms or different business models. While there are no other general limiting principles, there are such principles when the regulator issues a pro-competition intervention (PCI) and there remains some significant uncertainty on what the process for imposing these interventions will be. There are some suggestions that there may be a legal test that is similar to the existing market investigation regime in traditional competition policy, according to which the authority needs to prove that there is an adverse effect on competition.

Clarity on how to comply

The DMA proposal lacks guidance on how gatekeepers should comply with their obligations.[11] Similarly, Germany’s GWB10 does not provide much information on the level of specificity of obligations. By contrast, the proposed US “Access Act of 2021”, which exclusively targets interoperability issues, requires a “technical committee” to provide sufficient guidance on how to comply, potentially reducing uncertainty about compliance. With the exception of the proposed US “Ending Platform Monopolies Act”, the other two US proposals require the FTC and the Assistant Attorney General of the Antitrust Division to “not later than one year after the enactment of the Act issue guidelines outlining policies and practices relating to agency enforcement with the goal to promote transparency and deter violations”.

The UK proposal emphasises the need for compliance guidance to platforms. The proposal assumes there will be a close dialogue between the regulator and the SMS designate. Moreover, the regulation, which is based on “high-level objectives and principles” that “specify the behaviour expected of firms to comply with the code”, will be supported by “firm-specific guidance” that “sets out how the principles should be applied within a specific business model.”

2.3. Principle 3: dialogue, objective justification and appeal mechanisms

Finally, we will consider the third principle: the extent to which the proposed regulations allow for mechanisms that help the regulator to adapt and learn –– leading to regulations that are specific to the defined problem, proportionate and less damaging to the wider economy. On this score, the examined regulations differ –– and sometimes the differences are substantial.

Regulatory dialogue and objective justification

The DMA proposal provides limited scope for dialogue between the regulator and the businesses or “gatekeepers” that the regulation covers. Blacklisted obligations under Article 5 lack a procedure for regulatory deliberation and feedback loops from businesses. Obligations under Article 6(1), which deal for example with self-preferencing, interoperability measures and portability of data, are generally “susceptible of being further specified” –– potentially meaning that further specifications will allow businesses to seek guidance from the Commission if it is unclear how they are to comply with certain obligations.

Moreover, for Article 6(1) obligations a “gatekeeper may request the opening of proceedings pursuant to Article 18 for the Commission to determine whether the measures that the gatekeeper intends to implement or has implemented under Article 6 are effective in achieving the objective of the relevant obligation in the specific circumstances.” (Article 7(7)) Hence, for these obligations, platforms may have the right to present their case. This option is further specified: “A gatekeeper may, with its request, provide a reasoned submission to explain in particular why the measures that it intends to implement or has implemented are effective in achieving the objective of the relevant obligation in the specific circumstances.” Also, according to Article 30 of the DMA proposal, gatekeepers have the right to be heard and the right to get access to their file.

In addition, there is no clear possibility of so-called objective justifications weakening the ability for the Commission to consider trade-offs in enforcement. This means that Article 5 and Article 6 obligations may apply even if a designated gatekeeper can prove that certain conduct is effectively in line with the regulatory objectives and not harmful to competition or the contestability of markets. Only two very limited exceptions apply: the Commission may exceptionally suspend in whole or in part, a specific obligation laid down in Articles 5 and 6 if the gatekeeper can demonstrate that compliance would endanger the economic viability of the operation of the gatekeeper in the EU (Article 8(1)) or that it would adversely impact public morality, public health, and public security in the EU (Article 9).[12]

Germany’s GWB10 takes a different approach to matters of dialogue and objective justifications. According to Article 56 of GWB10, the German competition authority shall give the parties an opportunity to state their case. Furthermore, since GWB10 does not rely on self-executing obligations, it only empowers Germany’s competition authority to enforce the obligations by a reasoned decision “in order to ensure a sufficient degree of legal certainty for the undertakings”. Furthermore, Article 19a obligations, which cover self-preferencing, interoperability measures and measures that may impede users and competitors, shall not apply if the respective conduct is objectively justified, while the burden of proof is with the undertaking.

The proposed “American Choice and Innovation Online Act” allows for effective regulatory dialogue and an objective justification. The Act mandates the FTC to provide guidance on how the obligations will be enforced. It is likely that this guidance will involve dialogue with covered platforms, and the Act makes that clearer by allowing for affirmative defence, i.e. a defence based on facts other than those that support the regulator’s claim. In short, certain obligations shall not apply if the platform show that its conduct does not result in harm to the competitive process and was necessary to achieve a legitimate outcome, such as a reduction in discrimination or to protect user privacy or other non-public data.

By contrast, the other US bills offer only limited scope for regulatory dialogue and efficiency defence. The proposed US “Ending Platform Monopolies Act” as well as the proposed US “Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021” do not specify rules for regulatory dialogue and efficiency defence. It instead takes a general approach to these matters by mandating the FTC and the Department of Justice to enforce this Act in the same manner, and with the same duties as applicable in the FTC Act (15 U.S.C. 41 et seq.) or the Clayton Act (15 U.S.C. 12 et seq.) –– both of which provide some basic laws in US competition policy. According to the “US Access Act”, the FTC shall issue platform-specific standards of interoperability, and a technical committee under the FTC is further mandated to develop standards and implementation requirements. Obviously, since these requirements are platform-specific, it can be assumed that regulators will consult with the platforms.

The UK proposal seems to also allow for effective regulatory dialogue and an efficiency defence. Notably, the proposal includes limiting principles that can be applied when the regulator issues a “pro-competition intervention” (PCI) –– a decision to intervene against a firm in an ad hoc manner. The proposal assumes there will be a close dialogue between the regulator and the platform, or “SMS designate”.

Proportionality of remedies

The DMA lacks measurement of the proportionality of the imposed obligations with respect to the cost incurred for the benefit achieved. It is unclear how the remedies proposed relate to the extent of the abusive practices or the extent of consumer harm when an obligation has been violated. Compliance appears to be incentivised by way of fines, which can go up to 10% of the total turnover of the gatekeeper. The Commission may also impose periodic fines, and fines of up to 1% of the total turnover where a designated gatekeeper fails to comply with mainly procedural requirements. In the case of “systematic non-compliance”, the Commission could enforce proportionate structural measures, which could go as far as breakup and forced divestitures.

The remedies in Germany’s GWB10 are likely to be customised to the particular cases although the list of possible remedies is triggered at the moment of designation. Several provisions of the regulation also link fines to the economic significance of the abusive practices and the harm imposed on consumers. In the case of certain procedural violations, a fine of up to 1% of total sales can be imposed. And for material violations, fines can go up to 10% of the company’s turnover.

With the exception of the proposed US “Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021”, the proposed US bills do not require the FTC to assess and quantify consumer harm. Accordingly, the remedial actions are generally more divorced from the abusive practices and consumer harm, and fines can amount to high percentages of US revenues.[13] By contrast, the US “Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021” does not specify fines, but it allows for civil action. If the FTC has reason to believe that a covered platform violated the Act, the Commission may take civil action to recover a civil penalty under this Act and seek other appropriate relief in a District Court of the United States against the platform. The remedies considered in the UK proposal are also generally detached from abusive practices and consumer harm.[14]

Judicial review and appeal mechanisms

When acting under the DMA the Commission’s investigation powers will be subject to the full scope of fair process rights including the gatekeeper’s access to judicial review and possibility to challenge enforcement and sanctioning measures in accordance with the Treaties (Article 263 TFEU). In addition, the DMA specifically calls out that the Court of Justice of the European Union has unlimited jurisdiction with regard to the penalties provided for in the DMA (Article 35 DMA). This judicial review is akin to the one governing the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Articles 101 and 102 TFEU.

GWB10 explicitly states that platforms on multi-sided markets cannot appeal decisions to the Dusseldorf Higher Regional Court. Article 19a obligations are subject to limited possibilities of judicial review given the shortened judicial review process[15]. Contrary to the general competition policy, appeals can only be heard by the Federal Court of Justice (FCJ; Bundesgerichtshof), which shall decide as a court of appeal in the first and last instance on all related disputes. Companies other than platforms operating on multi-sided markets can still initiate legal action before a regional court, from where it can be appealed to the Court of Appeals and finally the FCJ.

All proposed US Acts grant the right to appeal equivalent to those granted in traditional US competition law enforcement. Generally, any decision by the regulator can be appealed to the Competition Appeal Tribunal. Decisions by the regulator to block mergers will also be subject to the same appeal standards that apply today. Similarly, according to the UK proposal, any decision by the regulator can be appealed to the Competition Appeal Tribunal. Decisions by the regulator to block mergers will also be subject to the same appeal standards that apply today.

[1] The focus of this part of the analysis will be on a) self-preferencing (a company giving preferential treatment to own offers over competitors’ offers), b) denying or hindering interoperability or portability of data, c) bans on processing and combining data from different sources (and thereby creating or raising market entry barriers), and d) leveraging market power (impeding competitors on a market, in which the company can rapidly develop its position even without being dominant, to prevent “tipping”).

[2] Also see, e.g., Koerber (2021) and Digital Europe (2021).

[3] This was also a key recommendation of the Digital Markets Taskforce, see https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases/digital-markets-taskforce.

[4] The UK proposal aims at establishing legally binding principals and business-specific codes of conduct – supervised by the new Digital Market Unit (DMU) at the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). It establishes a new regime to designate companies that have “Strategic Market Status”, the UK equivalent of a gatekeeper. These companies should meet certain criteria (“necessary conditions”): 1) substantial market power, 2) entrenched market power, and 3) strategic position. Finding substantial and entrenched market power is considered necessary in order to give the SMS designation, but not sufficient. The UK government argues that it is also necessary to show that the substantial and entrenched market position leads to a strategic position, which is further defined. Unless there is such a strategic position, the UK government argues that existing competition tools are sufficient to address any harm to consumers and competition.

[5] As concerns self-preferencing (Article 6(1)(d)), the rule seems to be relatively clear with regard to the favourable treatment in ranking of “services and products offered by the gatekeeper itself or by any third party belonging to the same undertaking compared to similar services or products of third party”. At the same time, the DMA proposal remains vague regarding the application of “fair and non-discriminatory conditions” in rankings. The rules are also vague with respect to the obligation to “provide to any third-party providers of online search engines, upon their request, with access on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms to ranking, query, click and view data in relation to free and paid search.” (Article 6(1)(j)) Additional guidance is provided by the European Commission’s case against Google/Alphabet about Google’s search “favouring its own comparison shopping service, a specialised search service, over competing comparison shopping services” (General Court of the European Union 2021).

[6] According to Article 19a(2)(1), Germany’s competition authority may prohibit an undertaking to “favour its own offers over the offers of its competitors when mediating access to supply and sales markets, in particular a) presenting its own offers in a more favourable manner; b) exclusively pre-installing its own offers on devices or integrating them in any other way in offers provided by the undertaking.”

[7] The Act propoes that “certain discriminatory conduct by covered platforms shall be unlawful”, and this includes self-preferencing and various vaguely formulated practices.

[8] The Act says it should be unlawful for a covered platform to “own, control, or have a beneficial interest in a line of business other than the covered platform that (1) utilizes the covered platform for the sale or provision of products or services”, or (2) “offers a product or service that the covered platform requires a business user to purchase or utilize as a condition for access to the covered platform, or as a condition for preferred status or placement of a business user’s product or services on the covered platform”, or (3) “gives rise to a conflict of interest”. With the exception of the term “conflict of interest”, the obligations are relatively clear and leave little room for interpretation.

[9] Also see, e.g., Koerber (2021) and Petit (2021). Several US proposals also fall into this category.

[10] According to Article 19a(2) GWB10 the Bundeskartellamt may prohibit an undertaking from1) favouring its own offers over the offers of its competitors when mediating access to supply and sales markets, 2) taking measures that impede other undertakings in carrying out their business activities on supply or sales markets where the undertaking’s activities are of relevance for accessing such markets,3) directly or indirectly impeding competitors on a market on which the undertaking can rapidly expand its position even without being dominant,4) creating or appreciably raising barriers to market entry or otherwise impeding other undertakings by processing data relevant for competition that have been collected by the undertaking, or demanding terms and conditions that permit such processing, 5) refusing the interoperability of products or services or data portability, or making it more difficult, and in this way impeding competition, 6) providing other undertakings with insufficient information about the scope, quality or success of the service rendered or commissioned, or otherwise making it more difficult for such undertakings to assess the value of this service, and 7) demanding benefits for handling the offers of another undertaking which are disproportionate to the reasons for the demand.

[11] Obligations under Article 6(1), which deals with self-preferencing, interoperability measures and portability of data, are generally “susceptible of being further specified”. According to Article 7(7), a “gatekeeper may request the opening of proceedings pursuant to Article 18 for the Commission to determine whether the measures that the gatekeeper intends to implement or has implemented under Article 6 are effective in achieving the objective of the relevant obligation in the specific circumstances.”

[12] The European Commission’s impact assessment indicates that policymakers have relatively limited knowledge about the impacts of the obligations on which the DMA proposal is built. This creates a legitimacy problem with regard to the existence of market abusive and anti-competitive effects, the more so since the current proposal relies on self-executing obligations and very limited possibilities for efficiency defence. This problem could be overcome through increased clarity of its political objectives, a more explicit formulation of its concepts and obligations, and limiting principles to blacklisted conduct. See, e.g. Petit (2021), for a similar argument.

[13] For example, in the proposed US “Ending Platform Monopolies Act” fines can amount to up to 15% of the total average daily US revenue of the person for the previous calendar year, or up to 30% of the total average daily US revenues of the line of business affected or targeted by the unlawful conduct during the period of unlawful conduct.

[14] The UK proposal includes two types of fines: a penalty for failure to provide complete information to the regulator (capped at 1% of worldwide turnover, going up to 5% in case of continued failure), and a penalty when a firm violates the Code or a pro-competition intervention, which has a statutory limit of 10% of worldwide turnover.

[15] According to Article 73(5) GWB10.

3. Policy Recommendations

The Digital Markets Act is an opportunity to prevent and remedy anti-competitive conduct by large digital platforms that, because of scale and network effects, have strong market power. If it is used in an adequate manner and targets specific problems, it is a legislation that can improve competition and the contestability of platform services markets and markets that to a high degree rely on digital services. However, the DMA also takes a novel approach to regulation, and novelty in regulation can lead to regulatory solutions and economic outcomes that later have to be corrected. For instance, several underlying studies for the DMA have pointed out that there is a delicate balance between, on the one hand, regulating platforms that use anti-competitive strategies in winner-takes-all markets and, on the other hand, the positive network effects of large platforms.[1] Fortunately, the EU is not alone in experimenting with new regulations that specifically target large digital platforms. There is great scope for the EU – and others – to learn from the choices made in similar regulations in Europe and the United States.

In this study, we have compared key parts of the DMA with similar legislative proposals in Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States –– in light of established principles for good regulation. The task has been to consider the structure and quality of regulation, not if it goes in a certain ideological, political or commercial direction. While all proposals have their strengths and weaknesses, we have found that there are some areas where the EU could learn from other proposals and improve the DMA, to make it more fit for purpose, and avoid unintended consequences on the economy.[2] The overarching conclusion is that a targeted objective of the DMA would help to increase competition and make digital markets –– those for platform services and those adopting platform services –– more contestable. This could lead to faster technology adoption and more investment in businesses, growth and technological change. In its current form, there are several ambiguities in objectives, concepts, and structure that risk leading to an ineffective regulation and a rising number of legal disputes: in other words, a platform and digital markets regulation that will not address the problems that motivates it in the first place.

Based on the analysis in this study, we recommend some changes of the DMA.

(1) Narrow and clarify the objectives and make it clear how the objectives relate to the adequacy of intervention.

Principles of good regulation start with the objective of a regulation. If objectives are clearly defined and not in conflict with each other, it is likely that the regulation will achieve its goal. However, if objectives are ambiguous, the effectiveness of the regulation will go down.[3] Some of the platform regulations examined in this study rely on established competition law frameworks to design their regulation. It usually follows that the regulation then has a clear symmetry between objectives and the proposed approach to intervention designed to address those objectives (for instance, the link between a clear objective to encourage competition and concepts of market dominance and market power). The German regulation, for instance, sits directly in a competition law framework. Some of the US proposals have a narrow set of objectives –– for instance on ownership and control or access and interoperability –– and therefore make it easier to structure other parts of the regulation in a way that is consistent with the objectives. The UK proposal combines both approaches –– at least to a certain extent. It is directly linked with established competition law and practices, and comes with principles and a smaller set of objectives to clearly link them to the proposed intervention.

The DMA could delineate its objectives more clearly. For instance, the objective of fairness could be better defined and the adequacy of intervention to foster competition as well as concepts and meanings of contestability in different contexts could be defined more precisely. Unless objectives can be given a clear meaning in a regulation, they are often not helpful for assessing the adequacy of the intervention and quality of a regulation. The EU should provide both a clearer definition of these two objectives and a guidance for how and when they link up with market interventions.

For example, it is not obviously clear what contestability means in platform markets. First, platforms or platform markets are too varied for one single approach of contestability to be meaningful. The market for online search is different from online retail –– let alone retail in a broader (offline) definition. Some platforms have actually reduced the barriers of entry to markets and therefore made some markets more contestable. Other platforms may have strong market dominance, but they still offer services that help platform users to contest other markets and compete with businesses and other platforms with strong market power. Hence, restrictions on platforms in the name of contestability as an identified objective of the regulation can make markets in which platform services are adopted less contestable. This seems not to be the outcome that the EU is seeking. Therefore, more guidance on how the regulation is designed to meet the objectives it sets out to achieve would make the DMA a better piece of regulation.

As the DMA rationale for intervention is not tied to the market characteristics in which digital platforms operate, the link between the objective of the regulation and how adequate the regulation is to meet those objectives is severed, increasing the risk of unintended consequences.

The alternative approach offered by the German GWB10 and the UK proposal is to make market investigations (or traditional competition policy concepts and instruments) part and parcel of the assessment of different aspects of contestability and how the regulations will work in practice. If the DMA follows that example, i.e., requiring the European Commission to conduct a market analysis before a designated gatekeeper needs to comply with an obligation, regulators could focus the attention on the specific market problems that motivated the DMA (e.g., market power caused by scale and network effects in multi-sided markets).[4] This is an established way to link the objectives of the regulation to the adequacy of the proposed intervention.

(2) The concept of “core platform services” could be clarified.

In the DMA proposal, the process and criteria for defining and designating a core platform service do not seem linked to the regulatory objectives nor to the particular characteristics of platform markets that motivate the DMA in the first place (e.g. strong network effects). In its current form, the selection process and criteria are at risk of giving advantages to certain technology and business models –– in contrast to the stated aims of having a neutral approach to the platform regulation. In the final opinion of the EU’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board, the selection of core platform services under the DMA remained a chief point of criticism –– or, using its words, it is a “significant shortcoming” that the DMA proposal cannot fully justify why some platform services are considered core (and should be covered by the DMA) but not others (e.g. content screening services).[5]

The UK proposal takes a different approach to the activity in scope and generally has a clearer relation between problem, designation/selection, and obligations. This can serve as guidance for the DMA and has also previously been pointed out in expert studies for the European Commission.[6] Alternatively, the EU could highlight some of the work that is associated with the proposed Act. For instance, there are already guiding principles in recitals 2, 3 and 4 of the DMA proposal that point to a more functional definition of core platform services. Accordingly, a new definition of “core platform services” that is closer to the market problems that the DMA seeks to remedy could rely on a combination of characteristics such as:

- extreme scale economies (nearly zero marginal costs to add business users or end users), strong network effects (ability to connect many business users with many end users through the multi-sidedness of these services), a significant degree of dependence of both business users and end users, lock-in effects, a lack of multi-homing for the same purpose by end users, vertical integration, and data driven- advantages (recital 2 of the DMA proposal),

- reduced contestability due to the existence of very high barriers to entry or exit, including high investment costs, which cannot, or not easily, be recuperated in case of exit, and absence of or reduced access to some key data (recital 3 of the DMA proposal), and

- serious imbalances in bargaining power to the detriment of prices, quality, choice and innovation therein (recital 4 of the DMA proposal).

There are several advantages with a functional definition –– apart from making the regulation more tailored to the core problem definition that is behind the new regulation of large platforms (solving the objectives and adequacy of intervention issues highlighted in point 1) . First, it would make the DMA more neutral towards the choice of technology and business models: it is rather the specific problematic characteristics that would be the basis for designations. Second, the enforcement by the European Commission would tie it closer to tried and tested competition tools, including market investigations, and strengthen the connection between the market problem and the regulatory remedy in the DMA. Third, greater clarity about designation criteria would increase predictability and reduce the risk of over-enforcement and other unintended costs. And fourth, as a functional definition would not target specific business models, it would likely have a less deterrent effect on competition and digital innovation by companies operating in Europe.

(3) The designation criteria for gatekeepers could be clarified and extended by additional parameters.

Like Germany’s GWB10, the designation of a gatekeeper in the DMA could take account of the actual market position. This is already a point of reference in the DMA. However, in order to make designation easier and more predictable, the proposal is based on quantitative metrics (e.g., number of users and turnover) and is at risk of becoming too occupied by platform size, an issue that the EU’s Regulatory Scrutiny Board highlighted in its review of the DMA.[7] In the German approach, an undertaking that is of paramount significance for competition across markets will have to feature more characteristics than just size, and these features would be linked to direct and indirect network effects, economies of scale arising in connection with network effects, data relevant for competition, and innovation-driven competition (Article 18(3a) GWB10). Such an approach would enable the EU to focus on the actual market problems and the abusive behaviour rather than to work with a “catch-all definition” that is at risk of making enforcement unwieldy.

Inspiration for such a change in the DMA can also be found in the UK proposal, which sets out the case for an evidence-based approach –– both in the legislation and in the actions that will be taken by the regulator. The UK promises to use a designation criteria that connect with the market problems and the market positions. The SMS designate will have “substantial” and “entrenched” market power, but also a strategic position in the market, “a position where the effects of its market power are likely to be particularly widespread or significant.” Furthermore, as the UK approach works with limiting principles when the regulator issues a “pro-competition intervention”, there is less risk that actions will be taken on companies that are just large rather than companies that are large and enjoy structural market advantages which allow them to reduce competition and encourage abusive practices.

Accordingly, the DMA proposal could be amended by adding additional criteria for the gatekeeper designation and, in line with recital 6 of the DMA proposal, rely on indicators to measure the “significance” of the “impact on the internal market”. These criteria could include those considered by Germany’s competition authority (Article 18(3a)), and generally take into account the important features referred to in recital 2 of the DMA proposal (particularly whether strong network effects and scale economies result in several lock-in effects on users, including the absence of multihoming). In addition, the DMA could be accompanied by clarifying guidelines with respect to the measurement of threshold criteria when it comes into force –– preceding delegated Acts on the basis of Article 3(5), which empowers the Commission “to specify the methodology for determining whether the quantitative thresholds are met”.

(4) Clarify obligations and how firms can comply with them.

The current obligations of the DMA proposal could be improved by more precisely defined obligations. The DMA has only little to say about the objectives of the individual obligations stated in Article 5 and Article 6(1), especially what they intend to achieve and how. Currently, many businesses do not know what individual obligations imply in practice, leaving them with uncertainty about their current conduct and whether the introduction of new features, services, and entire business models in the future would be allowed. Such types of uncertainty can have a chilling effect on the willingness to invest and innovate, which is why many principles of good regulation put an emphasis on clarity and the reduction of legal uncertainty.

Moreover, it is reasonable to infer from the DMA design that some of the obligations in the above-mentioned articles are only intended for some of the designated platforms (but not for others). However, this is not made clear in the proposal because the obligations are based on assumptions of general platform characteristics rather than market characteristics. Here, clarifications about what the obligations mean for the designated platforms would do a lot to alleviate uncertainty.

The US “American Choice and Innovation Online Act” and “Platform Competition and Opportunity Act of 2021” take a different approach, similar to the UK proposal. All three proposals mandate national competition authorities to provide detailed guidance on how to comply with the obligations. Inspiration can also be drawn from the proposed “US Access Act”, which requires covered platforms to maintain a set of transparent, third-party-accessible interfaces to enable the secure transfer of data to a user. This proposal obliges the US Federal Trade Commission to develop new portability and interoperability standards, together with implementing requirements.

This is an important part of aligning the DMA with the principles of good regulation. Businesses will have to know how to comply and what obligations are especially relevant to them. Therefore, the DMA would ideally provide general guidance as well as firm-specific guidance, setting out how the obligations should be applied within a specific business model.

(5) Better opportunities for regulatory dialogue and the right to defence.

All business regulations require a regulatory dialogue to achieve its outcome. For instance, other ex-ante regulations of markets like telecom and energy have evolved over a long period of time and been based on intensive dialogues between the regulator and the regulated businesses. This is necessary to ensure that the objectives and practices of a regulation fit with market characteristics and avoid that a regulation causes unnecessary and unintended costs. It is also central for the regulator to get relevant feedback from businesses about how regulations can improve. Lastly, a regulatory dialogue is also important for due process and the right of businesses to defend their practices.

The DMA proposal only allows for limited regulatory dialogue and only for one part of the substantive obligations. Enforcement under Germany’s GWB10 and in the UK proposal go in a different direction. The UK proposal assumes that there will be a close dialogue between the regulator and the UK equivalent of a gatekeeper (“SMS”). It also says that the regulator, in its Code of Conduct, should provide as much firm-specific guidance as possible, which necessitates a dialogue in the first place. Furthermore, the obligations in the German and UK approaches are – intentionally – not self-executing and provide opportunities for covered platforms to defend their practices. This is also an opportunity for regulatory dialogue. In Germany’s GWB10, for instance, exemptions from the obligations generally apply for practices that contribute to improving the production or distribution of goods or promoting technical or economic progress, while allowing consumers a fair share of the resulting benefits. The EU could follow the example of Germany and the UK.

[1] This point was discussed by the High-level Panel of Economic Experts at the EU’s Joint Research Centre. See Cabral et al. (2021).

[2] See, e.g. Copenhagen Economics (2021) and Oxera (2020).

[3] See OECD (2012a; 2021) and WEF (2021) for a discussion on objectives and outcomes.

[4] Notably, one of the underlying expert studies for the Impact Assessment of the New Competition Tool – a Commission analysis that preceded the DMA – makes an argument in this direction, preferring a regulatory approach based on market-structure problems and with an integration between a DMA-like regulation and existing competition tools. See European Commission (2020b).

[5] Regulatory Scrutiny Board (2020). Similar considerations are made in Teece and Kahwaty (2021).

[6] See, e.g., Crawford et al. (2020).

[7] The Regulatory Scrutiny Board (2020) concludes: “The report should make clearer how the problem drivers may lead to the identified negative outcomes. It should consider the negative consequences of curtailing the size advantages following from network economies and economies of scale for consumers. It should better distinguish problems relating to size advantages from the monopolisation of data and the imposition of market rules like exclusive dealings.”

References

Ash, E., Morelli, M. and Vannoni, M. (2021), More Laws, More Growth? Evidence from U.S. States, CEPR Discussion Paper 15629.

Braeken, D. and Hieselaar, T. (2021). An overview of Big Tech cases leading up to the Digital Markets, Act (DMA), 30 June 2021.

Bundeskartellamt (2021). Amendment of the German Act against Restraints of Competition. Important changes regarding the protection of competition in the digital economy. 19 January 2021.

Latham and Watkins (20210). The New German Digitalization Act: An Overview. 20 January 2021.

Cabral, L., Haucap, J., Parker, G., Petropoulos, G., Valletti, T. and Van Alstyne, M. (2021). The EU Digital Markets Act – A Report from a Panel of Economic Experts.

CERRE (2020). Digital Markets Act: Making economic regulation of platforms fit for the digital age. December 2020.

Copenhagen Economics (2021). The implications of the DMA for external trade and EU firms. Exploring the potential impact of the DMA in EU. 10 June 2021.

Crawford, G. S., Rey, P. and Schnitzer, M. (2020). An Economic Evaluation of the EC’s Proposed “New Competition Tool”. 16 October 2020.

Digital Europe (2021). Joint letter: Digital Markets Act endgame: European digital industry reaffirms three crucial priorities. 18 November 2021.

ECN (2021). Joint paper of the heads of the national competition authorities of the European Union. How national competition agencies can strengthen the DMA. June 2021.

European Commission (2021). Commission Staff Working Document on Better Regulation Guidelines. November 2021.

European Commission (2020a). Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act). 15 December 2020.

European Commission (2020b). Intervention triggers and underlying theories of harm, Expert advice for the Impact Assessment of a New Competition Tool, Expert study. European Commission, Directorate-General for Competition.

European Commission (2020c). Commission Staff Working Document, Impact Assessment Report Accompanying the document Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act), 15 December 2020.

European Council (2021). Regulating ‘big tech’: Council agrees on enhancing competition in the digital sphere. 25 November 2021.

European Parliament (2021). Compromise amendments on the draft report “on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act)” (2020/0374(COD)). Rapporteur for Report Andreas Schwab.

FBN (2020). Considerations of France, Belgium and the Netherlands regarding intervention on platforms with a gatekeeper position, 15 October 2020.

Ferracane, M.F., Kren, J, and van der Marel, E. (2020). Do data policy restrictions impact the productivity performance of firms and industries?. Review of International Economics.

General Court of the European Union (2021). Judgment in Case T-612/17. Google and Alphabet v Commission (Google Shopping), 10 November 2021.

ITIF (2021a). The Digital Markets Act: European Precautionary Antitrust. May 2021.

ITIF (2021b). ‘Self-Preferencing’ Can Be a Good Thing; ITIF Proposes New Taxonomy for Antitrust Regulators to Differentiate Competitive Benefits From Exclusionary Practices. October 2021.

ITIF (2021c). How Do Online Ads Work?. November 2021.

Jebelli, K. (2021). A Digital Market Regulator Fit For the Digital Age. Disruptive Competition Project. 13 October 2021.

Koerber, T. (2021). Lessons from the hare and the tortoise: Legally imposed self- regulation, proportionality and the right to defence under the DMA. NZKart 2021.

McKinsey (2020), How do companies create value from digital ecosystems?, 7 August 2020, https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/how-do-companies-create-value-from-digital-ecosystems.

Monopolkommisison (2021). Empfehlungen für einen effektiven und effizienten Digital Markets Act. Sondergutachten 82, 2021.

OECD (2006). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Alternatives to Traditional Regulation, 2006, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/42245468.pdf.

OECD (2012a). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance”, 2012, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory- policy/49990817.pdf.

OECD (2012b). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Regulatory Reform and Innovation”, 2012, https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/2102514.pdf.

OECD (2013). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Regulatory Cooperation: Addressing Global Challenges, 2013, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/international- regulatory-co-operation_9789264200463-en.

OECD (2014). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections, 2014, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/regulatory-enforcement-and-inspections- 9789264208117-en.htm.

OECD (2016). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Regulatory Cooperation: The Role of International Organisations in Fostering Better Rules of Globalisation, 2016, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/international-regulatory-co-operation_9789264244047-en.

OECD (2018a). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/governance/oecd-regulatory-policy-outlook-2018- 9789264303072-en.htm.

OECD (2018b). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit, 2018, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecd-regulatory-enforcement- and-inspections-toolkit_9789264303959-en.

OECD (2019). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Regulatory effectiveness in the era of digitalisation”, OECD Regulatory Policy Division, June 2019, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory- policy/Regulatory-effectiveness-in-the-era-of-digitalisation.pdf.

OECD (2020a) Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “Cracking the code: Rulemaking for humans and machines”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 42, October 2020, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/cracking-the-code_3afe6ba5-en.

OECD (2020b). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, One-Stop Shops for Citizens and Business, May 2020, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/one-stop-shops-for-citizens-and- business-b0b0924e-en.htm.

OECD (2020c). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Regulatory Impact Assessment, February 2020, http://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/regulatory-impact-assessment-7a9638cb-en. htm.

OECD (2021). Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Recommendation of the Council for Agile Regulatory Governance to Harness Innovation, October 2021, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0464.

Oxera (2020). The impact of the Digital Markets Act on innovation. Helping or hindering innovation and growth in the EU?, November 2020.

Petit, N. (The proposed Digital Markets Act (DMA). A legal and policy review. 11 May 2021.

Regulatory Scrutiny Board (2020). Regulatory Scrutiny Board Opinion on the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act), 10 December 2020.

Teece, D. J. and Kahwaty. H. J. (2021). Is the Proposed Digital Markets Act the Cure for Europe’s Platform Ills? Evidence from the European Commission’s Impact Assessment. 12 April 2021.

van der Marel, E., Kran, J. and Iootty, M. (2016). Services in the European Union : What Kinds of Regulatory Policies Enhance Productivity?. Policy Research Working Paper No. 7919, World Bank.

WEF (2021). Agile Regulation for the Fourth Industrial Revolution A Toolkit for Regulators, December 2020.

WTO (2021), Adapting to the digital trade era: challenges and opportunities, World Trade Organization 2021, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/adtera_e.pdf.