The Role of Trade Policy in Promoting Sustainable Agriculture

Published By: Fredrik Erixon Philipp Lamprecht

Research Areas: Agriculture EU Single Market European Union WTO and Globalisation

Summary

There is now a long history of countries improving sustainability standards in most parts of the economy while at the same time pursuing the ambitions of rules-based international trade and economic integration with other countries. It is not surprising that countries at the vanguard of sustainability also tend to be the countries that are most open to trade.

This Report looks closer at the interplay between the formulation of domestic standards and provisions in Free Trade Agreements that either acknowledge domestic standards or establish standards in a direct way. This interplay is crucial for two reasons: first to establish market access arrangements that help to promote sustainability standards, second to provide the policy basis to make standards and possible market access restrictions conducive to basic trade rules.

It lays a focus particularly on the growing importance of sustainability standards in international trade agreements, or Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) – in particular for the food sector. Such standards are relevant for all new high-ambition Free Trade Agreements – from the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership between eleven trans-pacific nations. The Report considers especially nine modern FTAs.

The purpose of the Report is to investigate how governments with high sustainability ambitions approach the issue of trade and sustainability – in particular how they work with, on the one hand, specific provisions in FTAs and, on the other hand, the development of domestic standards and their linkage to trade. The Report also looks directly at how these standards are designed, and what lessons that can be learned for governments that want to raise sustainability ambitions. It puts the results of the analysis in the context of Norwegian ambitions to improve its sustainability standards for food placed on the Norwegian market.

The analysis of how trade and sustainability have been made compatible starts with the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). These rules are important in their own right, but they also carry political significance. WTO-rules form the basis of the bilateral free trade agreements that countries sign with each other – and that now make up the main plank of international trade negotiations. In the language of the WTO, basic trade rules serve to protect the principles of national treatment and non-discrimination. Sustainability policies that are grounded on solid evidence and that follow international scientific norms will be compatible with WTO rules. Sustainability policies that confer advantages to domestic producers or that are arbitrary will get a harsh treatment.

Consequently, the bilateral free trade deals that the European Union or the European Free Trade Area (EFTA) have concluded with other parts of the world are not just compatible with WTO rules, they rely on these rules as the foundation stone. Moreover, these rules inform governments how they should organise their sustainability policy if they also want the opportunity to take part in modern trade agreements. If countries aren’t willing to play by these rules, they should also accept that they won’t be able to enjoy the benefits of trade agreements. What member countries of the WTO have agreed in past multilateral trade accords are not a blockage of sustainability policy, but they bar countries from pursuing such policies in a way that would lead to unequal application of trade rules – between home and foreign producers, or between different foreign producers.

In addition, it is of interest – also to the Norwegian policy discussion – to consider how EU policies are likely to change in the forceable future. The analysis provides a discussion of issues that are likely to remain very high on the agenda of the next European Commission. These include possible improvements in the TSD Chapters of trade agreements in particular with regard to enforcement mechanisms, the engagement of civil society, and climate action. Further policy highlights include a possible introduction of a carbon border tax, as well as the discussions related to due diligence of supply chains, and multilateralism.

In terms of conclusions, the Report identifies four main observations that should inform future policy development in Norway:

First, there is clearly a case to be made for aligning Norwegian trade policy to EU trade policy when it comes to provisions on trade and sustainability in Free Trade Agreements.

Second, there is a substantial body of scientific evidence, risk assessments and international experience of standards in areas that are related to sanitary and phyto-sanitary standards and to environmental standards which any government that want to raise sustainability standards can draw on.

Third, many countries struggle to formulate their domestic sustainability standards in a structured way. Arguably, this is a critical point for governments that are considering to introduce higher standards with consequence for market access for foreign producers. To avoid confusion or accusation of standards being a disguised trade restrictions, countries like Norway would have to structure and systematise its standards if the ambitions were to be raised and formed part of market access policy. A first step for a policy that seeks to condition import on the compliance with a stand is to make the standard clear and explicit.

Fourth, there are direct and indirect relations between domestic standards and provisions in FTAs. FTAs often deal with policies that cannot be directly formulated in a domestic standard, like some aspects of labour laws. They also deal with other forms of standards that need policy convergence in order to guarantee smooth trade between the contracting parties. Generally, it cannot be said that the EU or other entities use FTAs to “regulate” or to establish the standard. That rather happens bottom-up – through domestic regulations that later get reflected in trade agreements.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the able research assistance by Tatiana Kakara.

Introduction: Trade and Sustainability – Friends or Foes?

Old habits, it is said, die hard. This is certainly true for the debate about trade and sustainability. All too often, trade and sustainability are seen as foes rather than friends, or at least that they represent incompatible ambitions. For some, trade and the rules that govern trade openness stand in the way of the ambitions to improve the quality of the environment; they inevitably drive down the social and environmental standards of production in a noxious “race to the bottom”. For others, sustainability standards are a hidden way to favour domestic producers at the expense of foreign competitors, leading to higher prices for consumers and trade conflicts with other nations.

Both of these views are wrong. There is now a long history of countries improving sustainability standards in most parts of the economy while at the same time pursuing the ambitions of rules-based international trade and economic integration with other countries. It is not surprising that countries at the vanguard of sustainability also tend to be the countries that are most open to trade. The trend is also clear. Firstly, the production standards that consumers expect of the goods and services they are purchasing are increasing, and this applies particularly to food. There has been a sharp increase in consumer awareness and the preferences they have for sustainable production. Secondly, governments are setting higher demands for products and production processes, and these demands manifest themselves in regulations, standards and the acknowledgement of various voluntary standardisation schemes. Thirdly, most governments that now negotiate and sign international trade agreements put significant emphasis on ensuring that new market access will not dilute sustainability standards. On the contrary, provisions on trade and sustainability are now designed in order to promote higher sustainability standards.

This Report will cover all three elements, but the focus is particularly on the growing importance of sustainability standards in international trade agreements, or Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) – in particular for the food sector. Such standards are relevant for all new high-ambition Free Trade Agreements – from the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership between eleven trans-pacific nations. The purpose of the Report is to investigate how governments with high sustainability ambitions approach the issue of trade and sustainability – in particular how they work with, on the one hand, specific provisions in FTAs and, on the other hand, the development of domestic standards and their linkage to trade. Furthermore, the Report intends to put the results of the analysis in the context of Norwegian ambitions to improve its sustainability standards for food placed on the Norwegian market.

The Starting Point: Rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO)

The analysis of how trade and sustainability have been made compatible starts with the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO). These rules are important in their own right, but they also carry political significance. WTO-rules form the basis of the bilateral free trade agreements that countries sign with each other – and that now make up the main plank of international trade negotiations. Consequently, the bilateral free trade deals that the European Union or the European Free Trade Area (EFTA) have concluded with other parts of the world are not just compatible with WTO rules, they rely on these rules as the foundation stone. Moreover, these rules inform governments how they should organise their sustainability policy if they also want the opportunity to take part in modern trade agreements. If countries aren’t willing to play by these rules, they should also accept that they won’t be able to enjoy the benefits of trade agreements. What member countries of the WTO have agreed in past multilateral trade accords are not a blockage of sustainability policy, but they bar countries from pursuing such policies in a way that would lead to unequal application of trade rules – between home and foreign producers, or between different foreign producers.

In the language of the WTO, basic trade rules serve to protect the principles of national treatment and non-discrimination. Whenever a domestic policy measure related to sustainability (most often, an environmental regulation or a food standard) have been seen to violate WTO rules, it has happened predominantly because the measures have been designed in a way that is discriminatory and that extends benefits (e.g. market access) to some producers in a way that doesn’t serve the sustainability purpose. These examples are important and it is worth getting to the heart of what WTO rules entail for countries that wish to apply sustainability standards on goods that are imported.

It is sometimes lazily argued that the WTO can agree to anything as long as a domestic measure – with trade distorting effects – is associated with environmental protection. The argument is that GATT Article XX, as a general exemption clause, authorises discrimination when it is adopted for a legitimate purpose. This view, however, is based on a selective reading of previous GATT disputes incorporating Article XX and makes the mistake of claiming that the declared intention is what really matters. However, only because an intention conforms to legitimate deviations from GATT rules it doesn’t mean that deviations can be authorised: the policy design matters crucially. Likewise, it is equally lazily argued by some that the WTO ruling against EU bans on hormone treated beef goes to show that WTO rules institute policy regimes that doesn’t allow for governments to take adequate concern for sustainability. The two examples are different, but they are united in critical aspects: policy design, the role of scientific evidence supporting an action that damages trade, and how countries have gone about establishing a certain standard.

At the heart of this discussion is GATT Article I concerning treatment of like products, a crucial concept in WTO jurisprudence. It sets out one of the core principles of the GATT/WTO system: like products should be treated equally. In the words of the Article:

“With respect to customs duties and charges of any kind imposed on or in connection with importation or exportation or imposed on the international transfer of payments for imports or exports, and with respect to the method of levying such duties and charges, and with respect to all rules and formalities in connection with importation and exportation, and with respect to all matters referred to in paragraphs 2 and 4 of Article III, “any advantage, favour, privilege or immunity granted by any contracting party to any product originating in or destined for any other country shall be accorded immediately and unconditionally to the like product originating in or destined for the territories of all other contracting parties.”

Likeness is important for sustainability policies because if, for example, Norway would introduce a food standard that raises the cost of production in Norway, it would want to ensure that imported food followed the same standard. However, the risk is that exporters to Norway would say that Norway cannot impose a market access restriction on imported goods that don’t follow the food standard in Norway, because the two products are “like”, even if they are produced under different sustainability standards. What complicates the matter is that “likeness” is not defined in this GATT article or in GATT Article III, which establishes the principle of likeness in national treatment. Case law, however, offers interpretations. Two unadopted Panel reports have ruled that products are not unlike just because there are differences in production methods when these differences do not affect the physical characteristics of the final product.[1] Even if these reports were unadopted, they can, as later cases have shown, be “useful guidance”[2] for how a WTO would consider new cases. In rulings from the Appellate Body (AB), four criteria have consistently been used to define likeness. These criteria derive from the GATT Working Party in 1970:[3]

- The properties, nature and quality of the products; that is, the extent to which they have similar physical characteristics.

- The end-use of the products; that is, the extent to which they are substitutes in their function.

- The tariff classification of the products; that is, whether they are treated as similar for customs purposes.

- The tastes and habits of consumers; that is, the extent to which consumers use the products as substitutes – determined by the magnitude of their cross elasticity of demand.

These criteria aren’t the best standard to use for determining likeness in the modern world economy (the criteria were developed to serve a different purpose) and subsequent cases have therefore gradually specified the likeness criteria and when environmental impacts are a legitimate reason to treat otherwise similar products as unlike.[4] In one case, the Appellate Body ruled that consumer perceptions are relevant when considering “likeness” and subsequent cases, e.g. on biofuels, have clearly made the case that likeness cannot be established just because different products fall within the same tariff classification. On the back of other international agreements, it has also been gradually clarified that products can be seen as unlike if there are clear domestic standards in place that have the effect of making goods to follow a uniform sustainability norm. Important cases (e.g. Brazil – Re-treaded Tyres) have established that likeness can be deviated from if there is a “rational connection” between a measure and the stated goal, leading to an avoidance of “arbitrary and unjustifiable discrimination”. Finally, work on sanitary and phyto-sanitary (SPS) matters in the WTO and in international standardisation bodies (codex ailmentarius) have gone a long way of acknowledging the scientific evidence behind certain sustainability criteria.

All these examples point us back to the policy design and the scientific support for a sustainability policy to have consequences for market access. If sustainability policies are designed with weak scientific support and have discriminatory consequences, it is likely that the WTO would take notice of “the design, architecture and revealing structures” because they indicate an intention to “conceal the pursuit of trade-restrictive objectives”.[5] Similarly, there is a difference between countries that have adopted a standard and those countries that have done so after series of consultations that have allowed other countries to comment on the actual policy design. Sustainability policies that are grounded on solid evidence and that follow international scientific norms will be compatible with WTO rules. Sustainability policies that confer advantages to domestic producers or that are arbitrary will get a harsh treatment.

Trade and Sustainability – Overview and Analysis of Policy Discussion at EU-level

EU policies on FTAs and sustainability are central to the analysis in this Study. Consequently, it is of interest – also to the Norwegian policy discussion – to consider how EU policies are likely to change in the forceable future. Provisions on trade and sustainable development have been at the heart of EU trade agreements since 2010. All new EU trade and investment agreements include a chapter on sustainable development (“TSD Chapter”) that upholds and promotes social and environmental standards. Almost ten years have passed since the first TSD chapters, and a variety of improvements and policy updates regarding sustainability are being discussed at EU level.

Our analysis provides an overview of the current and future policy discussion at EU-level regarding sustainability and trade. More specifically, issues that are likely to remain very high on the agenda of the next European Commission are discussed. These include possible improvements in the TSD Chapters of trade agreements in particular with regard to enforcement mechanisms, the engagement of civil society, and climate action. Further policy highlights include a possible introduction of a carbon border tax, as well as the discussions related to due diligence of supply chains.

Improving the TSD Chapters: Enforceability, Climate action, Civil Society Engagement

Specific demands from the European Parliament to improve the TSD Chapters concern in particular the issue of weak enforcement of TSD chapters and the lack of transparency. MEPs, in particular from the S&D group and the Greens, stress the need for more assertive enforcement of the TSD chapters. While the TSD chapters promote the environmental, social and economic pillars of sustainability, there is a need to ensure that they are effectively enforced in case of non-compliance of the trade partner, so that sustainability standards are not lowered.

The EU model in place when it comes to enforcement and dispute settlement is to engage with governments and the civil society, setting up a panel and producing reports and recommendations, condemning actions of trade partners that contradict the EU’s sustainability standards. For instance, when it comes to labour, the EU recently moved ahead with dispute settlement and will produce a critical report with recommendations regarding South Korea and its lack of delivery on its labour commitments under the FTA with the EU.[6]

To ensure the enforcement of the TSD chapter, some voices have even proposed an inclusion of trade sanctions. However, since there is no consensus between Member States, and since the Commission deems it impossible to adapt a trade sanctions approach, while maintaining the very broad scope of its agreements, this option remains off the table. The mechanisms of cooperation and engagement, including the work of the Domestic Advisory Groups and the provisions on dispute settlement, are the options used by the EU to build up pressure and ensure that the trade partners maintain high sustainability standards. Therefore, finding ways to enhance and improve these cooperation and engagement mechanisms are likely to be the cornerstone of relevant policy discussions in the future.

Apart from the implementation of TSD Chapters, important areas of focus are climate change and the environment, cooperation and transparency, as well as the need for further engagement of civil society. To address these concerns, in February 2018, a non-paper was published by the European Commission services which presented a 15-point action plan to improve the TSD Chapters in the EU FTAs.[7] The action plan includes a number of important actions to enhance the sustainability promotion in EU FTAs, such as: a closer cooperation between the Commission, Member States and the EP, as well as with International Organisations; engaging civil society in monitoring activities and regarding responsible business conduct; preparing a Handbook for implementation of the TSD Chapter and stepping up resources; stepping up climate action and enhancing communication and transparency. In order to strengthen trade and labour provisions of TSD chapters – apart from encouraging partners towards the early ratification of core international agreements – the Commission in particular aims at including reinforced provisions on labour in its future agreements by extending commitments beyond ILO core labour standards to also cover labour inspection, as well as health and safety at work (in line with the related ILO conventions).[8]

Carbon Border Tax, Due Diligence, and Multilateralism

As far as the nexus trade-sustainability-climate change is concerned, the EU is already stepping up its efforts in its FTAs, which include binding commitments under the Paris Agreement. A very recent issue that is being discussed is the introduction of a carbon border tax.[9] A carbon border tax would mean introducing a tax on the carbon content of imported goods at EU borders, thereby imposing fees on carbon-intensive products. As far as the trade aspect of this measure is concerned, the EU will need to ensure that such a measure would be implemented in a non-discriminatory way, by respecting WTO rules, which demand that border carbon adjustments do not discriminate at the border and among trade partners by singling out specific countries. Instead, the charge must be based on the carbon content of products.[10] Trade Commissioner Malmström affirmed in the last meeting of the Committee on International Trade of the EP (INTA Committee meeting on 23 July 2019) that carbon border tax will be an important issue for the upcoming Commission.[11] In addition, political guidelines of the incoming Commission president announced investigations on a carbon border tax and stressed the overall importance of a “European Green Deal”.[12]

A further discussion on trade and sustainability revolves around concerns voiced by the European Parliament with regard to the fabric and garment industry. More specifically, the sector has often come under scrutiny because of human rights and labour rights abuses. MEPs have called for a reporting system to provide full transparency on product value chains and demanded legislation to create binding human rights due diligence obligations for supply chains in the garment sector.[13] The Commission responded by launching the “garment initiative”[14], which has not produced concrete outcomes yet and includes actions only on a voluntary basis. Voices in the EP have, however, requested to move past the voluntary basis and adopt binding legislation on due diligence obligations for supply chains. So far, only France has adopted relevant binding national legislation in 2017, requiring French companies to prevent negative impacts on the environment and human rights and to pay compensation if they fail to comply and abuses occur. Adopting binding EU-wide legislation on due diligence is not envisaged by the Commission currently but will probably remain at the forefront of future discussions, especially at European Parliament level.

Moreover, the year 2019 is also vital for the EU to help broker consensus on diverging WTO reform positions ahead of the 2020 WTO Ministerial Conference in Astana.[15] Together with the US and Japan, the EU is looking to drive the reform discussions forward. Playing a decisive role in reforming the WTO is therefore expected to remain a trade policy priority for the EU, also with regard to sustainability.

Finally, the political aspect will also be crucial for the future developments in trade policy discussions. The promotion of values-based trade and sustainability through FTAs has been a political priority for the current Commission. Under the “Trade for All” Strategy[16] important agreements have been finalised (most recently Japan, Mercosur, Vietnam). However, given the current geopolitical uncertainties, including the turbulences in EU’s trade relations with the US, it remains to be seen whether and to what extent the trade priorities for the EU could change when the new Commission takes over.

Structure of this Study

In this Study we will look closer at the interplay between the formulation of domestic standards and provisions in Free Trade Agreements that either acknowledge domestic standards or establish standards in a direct way. This interplay is crucial for two reasons: first to establish market access arrangements that help to promote sustainability standards, second to provide the policy basis to make standards and possible market access restrictions conducive to basic trade rules.

In Part I we will provide an analysis of FTAs with the purpose of getting a better understanding of how high-ambition FTAs approach sustainability standards. The Study considers especially nine modern FTAs. In part II we will look much more directly at how these standards are designed, and what lessons that can be learned for governments that want to raise sustainability ambitions. The chapter looks especially at Norway. The final chapter provides a conclusion.

[1] GPR, US-Tuna (Mexico); GPR, US-Tuna (EEC)

[2] ABR, Japan-Alcoholic Beverages

[3] GATT (1970).

[4] ABR, EC-Asbestos

[5] PR, EC-Asbestos; PR, US-Shrimp; PR, Brazil-Retreaded Tyres.

[6] Brussels, 5 July 2019, “EU moves ahead with dispute settlement over workers’ rights in Republic of Korea”: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=2044.

[7] Non-paper of the Commission services, February 2018, “Feedback and way forward on improving the implementation and enforcement of Trade and Sustainable Development chapters in EU Free Trade Agreements”: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/february/tradoc_156618.pdf

[8] European Commission, February 2019, Stocktaking of the 15-point action plan: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regexpert/index.cfm?do=groupDetail.groupMeetingDoc&docid=28196.

[9] CEPS Publication, May 2010, “Climate Change and Trade: Taxing Carbon at the Border?”: https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Climate%20Change%20and%20Trade.pdf.

[10] Climate Home News, July 2019, “How von der Leyen could make a carbon border tax work”: https://www.climatechangenews.com/2019/07/22/von-der-leyen-make-carbon-border-tax-work/.

[11] Brussels, 23 July 2019, INTA Committee Meeting: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/ep-live/en/committees/video?event=20190723-1030-COMMITTEE-INTA.

[12] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/mission-letter-frans-timmermans-2019_en.pdf

[13] Euractiv, June 2019, “From ‘liberalise and patronise’ to a genuine sustainable trade strategy for the EU”: https://www.euractiv.com/section/economy-jobs/opinion/from-liberalise-and-patronise-to-a-genuine-sustainable-trade-strategy-for-the-eu/.

[14] EU Garment Initiative: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-europe-as-a-stronger-global-actor/file-eu-garment-initiative.

[15] EU Parliament Study, January 2019 “10 issues to watch in 2019”: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2019/630352/EPRS_IDA(2019)630352_EN.pdf.

[16] European Commission, October 2015, “Trade for All: Towards a more responsible trade and investment policy”: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2015/october/tradoc_153846.pdf.

1. Comprehensive FTA Analysis to identify International Best Practices

1.1 Introduction

Sustainable development has become an increasingly important topic in international trade policy. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) have reflected this development over time by covering an expanding scope of sustainability measures and incorporating precise language. Originally, only a handful of countries incorporated sustainability provisions in their agreements; now they are a standard feature in most FTAs. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was the first US agreement to link trade and sustainable development. The EU was another forerunner on the issue and sustainable development has become one of the European Commission’s guiding principles for its trade policy. Indeed, dedicated chapters on Trade and Sustainable Development have been included in all of its FTAs since the EU-South Korea FTA was adopted in 2011.

Moreover, the scope of sustainability issues in FTAs has gradually increased, covering not only human rights, but also specific labour and environmental issues. Over time, also the language evolved beyond mere dialogue provisions towards more substantive provisions: agreements increasingly used specific language on cooperation as well as enforcement mechanisms, procedural guarantees and dispute settlement procedures as well as market access conditions. Countries also progressively highlighted the importance of international standards in FTAs, for example by referencing multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) which also set out specific trade obligations, or by reaffirming relevant ILO declarations on social sustainability.

Considering these different types of provisions, there are mainly two ways in which sustainability provisions in FTAs can relate to domestic standards. The first way is by referencing international agreements or declarations such as the MEAs or ILO declarations in the FTAs and requiring them to be manifested in domestic law of the parties. This can be done by reaffirming commitments or obligations under these agreements, or by stating the need of domestic law to reflect specific agreements or declarations.

A second way is by introducing specific market access conditions, such as trade conditions or import requirements related to sustainability measures. They are normally accompanied by provisions that outline what happens when countries diverge on their domestic standards, or how they tackle procedural differences in their regulatory systems or standards, and the way that compliance with them are ensured. These provisions can be related to equivalence, science and risk analysis, audits, import checks, regional conditions and dispute settlement.

In this chapter we will provide a comparison on how different FTAs address various measures of sustainability. The comparative analysis of the FTAs is focused on different main themes identified. The FTA provisions have been divided into five different overarching themes. Four of these themes cover the first way in which sustainability can relate to domestic standards. These themes are: labour, the environment, trade and sustainable development (TSD), as well as enforcement and cooperation mechanisms. A fifth theme, market access, covers the second way.

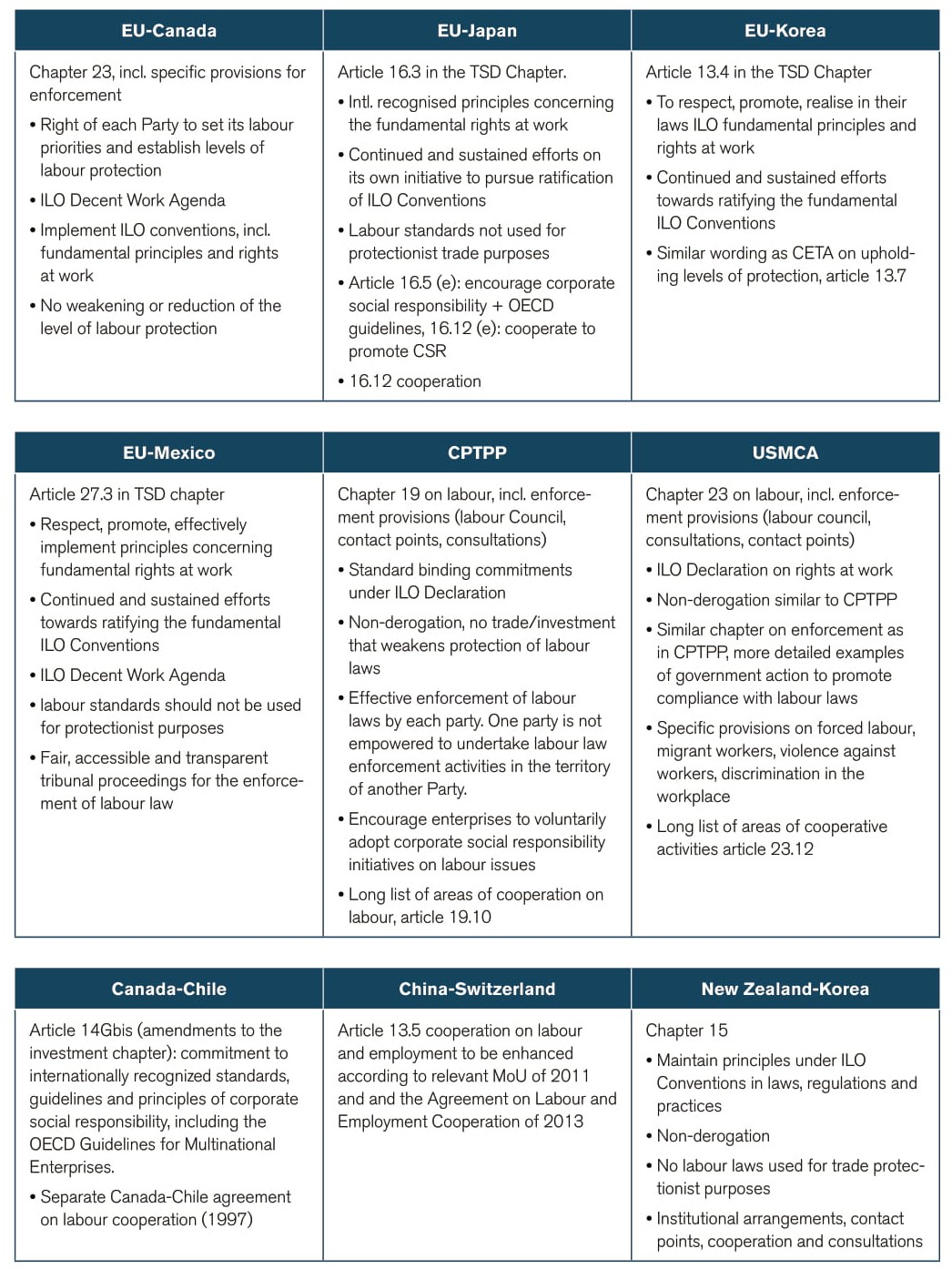

1.2 Labour

All the agreements covered in this analysis include the standard binding commitments to maintain the fundamental principles of ILO Conventions in the parties’ laws, regulations and practices. For example, the labour chapter of the CPTPP requires parties to uphold through its domestic law the ILO Declaration. This includes the freedom of association and collective bargaining, the elimination of forced labor, the abolition of child labor and the elimination of employment discrimination. Ratification of the fundamental ILO Conventions is to be pursued in the EU FTAs (with Japan, Korea and Mexico). EU-Canada, EU-Korea and EU-Mexico make reference also to the ILO Decent Work Agenda, which, however, is not mentioned in the EU-Japan EPA.

Concerning the upholding of standards, the existing labour standards may not be lowered or not enforced to increase trade and investment (CETA, EU-Korea). Similarly, CPTPP and USMCA include an article on non-derogation. It is inappropriate to encourage trade or investment by weakening or reducing the protections afforded in each Party’s labour laws. No Party shall derogate from its statutes or regulations implementing labour rights in a manner affecting trade or investment between the parties and labour standards should not be used for protectionist purposes (EU-Japan, EU-Mexico, New Zealand-Korea).

CPTPP and USMCA include an article laying down that no party shall fail to effectively enforce its labor laws. They both also include a long list of areas of cooperation on labour (Art. 19.10 and 23.12 respectively). The USMCA labour chapter includes new provisions to take measures to prohibit the import of goods produced by forced labor, to address violence against workers exercising their labor rights, and to ensure that migrant workers are protected under labor laws. Canada and Chile have a very detailed, separate agreement on labour cooperation. The Canada-Chile FTA created a work plan to promote the exchange of information and knowledge between both countries. A provision for complaint and conflict resolutions procedures in relation to labour laws facilitates solutions without resorting to formal channels of dispute resolution. In the China-Switzerland FTA, cooperation on labour and employment is regulated in article 13.5, according to which parties “shall enhance their cooperation on labour and employment” according to an MoU and an Agreement on Labour and Employment Cooperation between the parties.

Explicit provisions on corporate social responsibility (CSR) can be found in the EU-Japan EPA in Art. 16.5 (e) and cooperation on CSR in Art.16.12 (e); in the CPTPP, enterprises are encouraged to voluntarily adopt CSR initiatives on labour issues. Also the amendments to the investment chapter of the Canada-Chile FTA (Art. 14Gbis) include CSR provisions. A new, dedicated article on CSR was created which reaffirms the parties’ commitment to globally endorsed CSR standards. The update also includes procedural enhancements to the investor-state dispute settlement mechanism with respect to preliminary objections, awarding of costs, ethical considerations, third-party funding, and transparency. Furthermore, the parties have added provisions that encourage alternatives to arbitration, such as mediation and consultation.

The agricultural sector can be sustainable, if it is not only ecologically, but also socially responsible. Moreover, sustainable agriculture is more labour intensive than conventional farming.[1] Therefore upholding international and domestic labour standards and addressing labour issues through FTAs is key for the promotion of sustainability in the agri-food sector.

1.3 Environment

The Canada-Chile FTA includes a separate Canada-Chile Agreement on Environmental Cooperation. The Agreement has fostered capacity-building and collaborative research on issues of importance to Canada and Chile. Recent cooperative activities have focused on protected areas, climate change, conservation of shared migratory species, contaminated sites, air quality, environmental information systems, chemicals management, indigenous participation in environmental decision-making, and greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

All of the other FTAs make reference to MEAs that the two parties have signed. The agreements emphasize the importance of MEAs and reaffirm commitment of the parties to implement the MEAs to which they are party. The EU-Japan EPA is the first ever EU FTA to make explicit reference to the Paris Agreement (and UNFCC which is also mentioned in the EU-Mexico GA).

The new sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) chapter of the modernised Canada-Chile FTA provides scope for better communication and cooperation to address issues in agricultural products while maintaining the rights of parties to take measures necessary for the protection of human, animal or plant life or health. Such provisions protect agricultural products while limiting trade-distorting effects as much as possible. The chapter modernises the existing bilateral SPS committee previously established by the CCFTA Trade Commission and strengthens the bilateral institutional framework for addressing and seeking to resolve future SPS related issues.

The new TBT chapter of the Canada-Chile FTA includes commitments that enhance the WTO TBT Agreement in areas such as transparency, conformity assessment and joint cooperation, along with a mechanism to address specific TBT issues should they arise. Additionally, the chapter includes annexes on icewine and organics. The icewine annex requires Chile to ensure that any products labelled as icewine are made exclusively from grapes naturally frozen on the vine. The annex on organic products will help facilitate trade by encouraging continued work on the equivalence of organic certification systems, as well as communication and cooperation related to organic products.

EU-Japan, EU-Mexico, CPTPP and USMCA include provisions on biological diversity/biodiversity, with the EU agreements explicitly mentioning the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and EU-Mexico also referring to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

The Environmental Chapter of CPTPP includes similar environmental clauses to pre-existing EU FTAs, which, however, did not go as far as CPTPP. It has both binding and non-binding commitments relating to environmental protection. The binding obligations prohibit a party from failing to effectively enforce its environmental laws in a manner affecting trade or investment between the parties, and waiving or otherwise derogating from its environmental laws in order to encourage trade or investment between the parties.

The modernised EU-Mexico Global ‘agreement in principle,’ includes a standalone chapter (Chapter 6) on animal welfare cooperation, separating the issue from sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures. It is the first time an FTA has a chapter dedicated to conditions for livestock. It includes reference to the principle of ‘animal sentience,’ a European value enshrined in article 13 of the ‘Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’ but which is currently not reflected in Mexican Federal Law.[2]

Moreover, there are a number of other interesting new provisions on antimicrobial resistance (AMR). For AMR, both parties recognise the importance of tackling the global threat and have agreed to work together on both a multilateral and bilateral level to control it. They commit to phase out the use of some substances such as growth promoters (Chapter 6), and to promote and support international standards and cooperation in multilateral fora.

Finally, the EU-Mexico FTA creates stronger hygiene standards. The EU and Mexico maintain their right to establish a level of protection that they consider appropriate and the agreement contains reference to the precautionary principle in decision-making. As already enshrined in EU treaties, this principle foresees that products can be kept out of the market if there is no scientific certainty of their safety. In addition, the agreement increases mutual transparency and information exchange. Mexico also agreed to treat the EU as a single entity, thus eliminating separate procedure for individual member states.

The environment chapter of USMCA includes the most comprehensive set of enforceable environmental obligations of any previous US agreement, including obligations to combat trafficking in wildlife, to strengthen law enforcement networks to stem such trafficking, and to address pressing environmental issues such as air quality and marine litter.[3] In a non-binding section on environmental goods, USMCA does reference ‘clean technology’ as a desired path while also highlighting ‘carbon storage’ in the section on sustainable forest management (article 24.23). In terms of conservation, the USMCA identifies a range of environmental and conservation topics to be addressed through trilateral cooperation. These include including tackling illegal trade in forest products, combating marine plastic litter and reducing alien invasive species (chapter 24).

1.4 Trade and Sustainable Development (TSD)

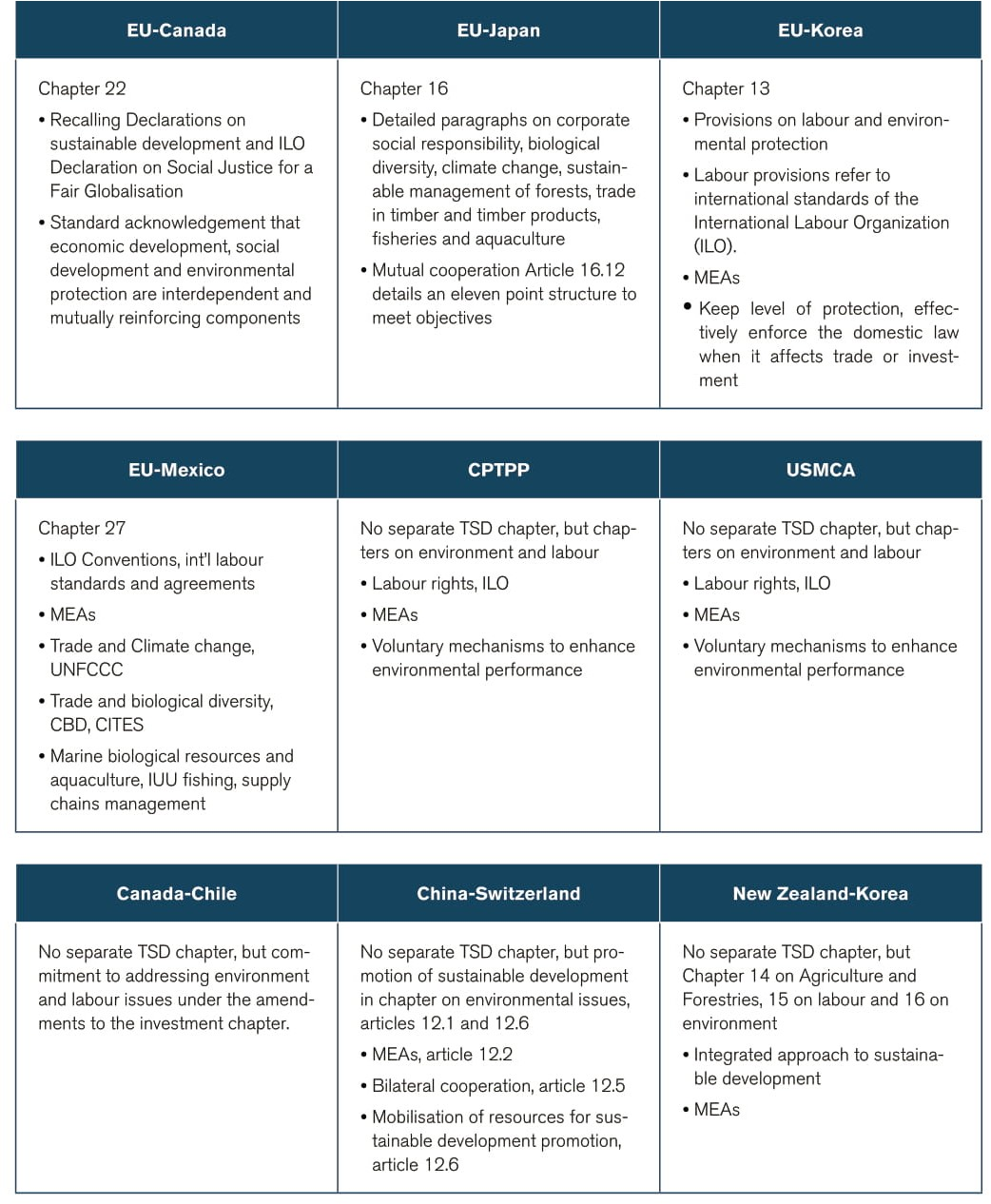

Separate TSD chapters are included in EU FTAs (EU-Canada, EU-Japan, EU-Korea, EU-Mexico). CETA is the only agreement to include separate chapters on “Trade and Environment” and “Trade and Labour”, apart from the TSD chapter. The other five non-EU agreements do not have a separate TSD chapter, but they include similar provisions within their Environment or Labour Chapters.

The TSD chapters in EU agreements include provisions on labour and environmental protection. The labour provisions in these agreements refer to international standards of the ILO. When it comes to labour standards, the TSD chapter requires compliance with internationally recognised labour standards namely the ILO core labour standards and ILO Conventions. The environmental provisions refer to international agreements and the MEAs they have signed.

In regard to already existing domestic law, the TSD chapter in the EU-Korea agreement includes the commitment to keep the level of protection and to effectively enforce the domestic law when it affects trade or investment. These commitments ensure that lowering standards is not used for competitive advantage. Equivalent provisions in the EU-Japan EPA can be found in Article 16.2 and in Article 27.2 of the EU-Mexico GA.

The EU-Japan and EU-Mexico TSD chapters include particular references to biodiversity, which is essential for the sustainable production of food and agricultural products. In the EU-Mexico GA, emphasis is put on the need to ensure conservation. The EU-Japan agreement uses weaker wording, only recognizing the contribution of trade in ensuring conservation of biodiversity.

Both EU-Japan and EU-Mexico include particular references to climate change. In the CETA, there is no dedicated section or mention of climate change, nor to the UNFCCC or the Paris Agreement, or any mention of trade and transition to low GHG energy. However, the joint interpretative statement published on 14th January 2017 confirms that the parties commit to cooperate on trade-related environmental issues including climate change and the implementation of the Paris Agreement.[4]

1.5 Enforcement and Cooperation Mechanisms

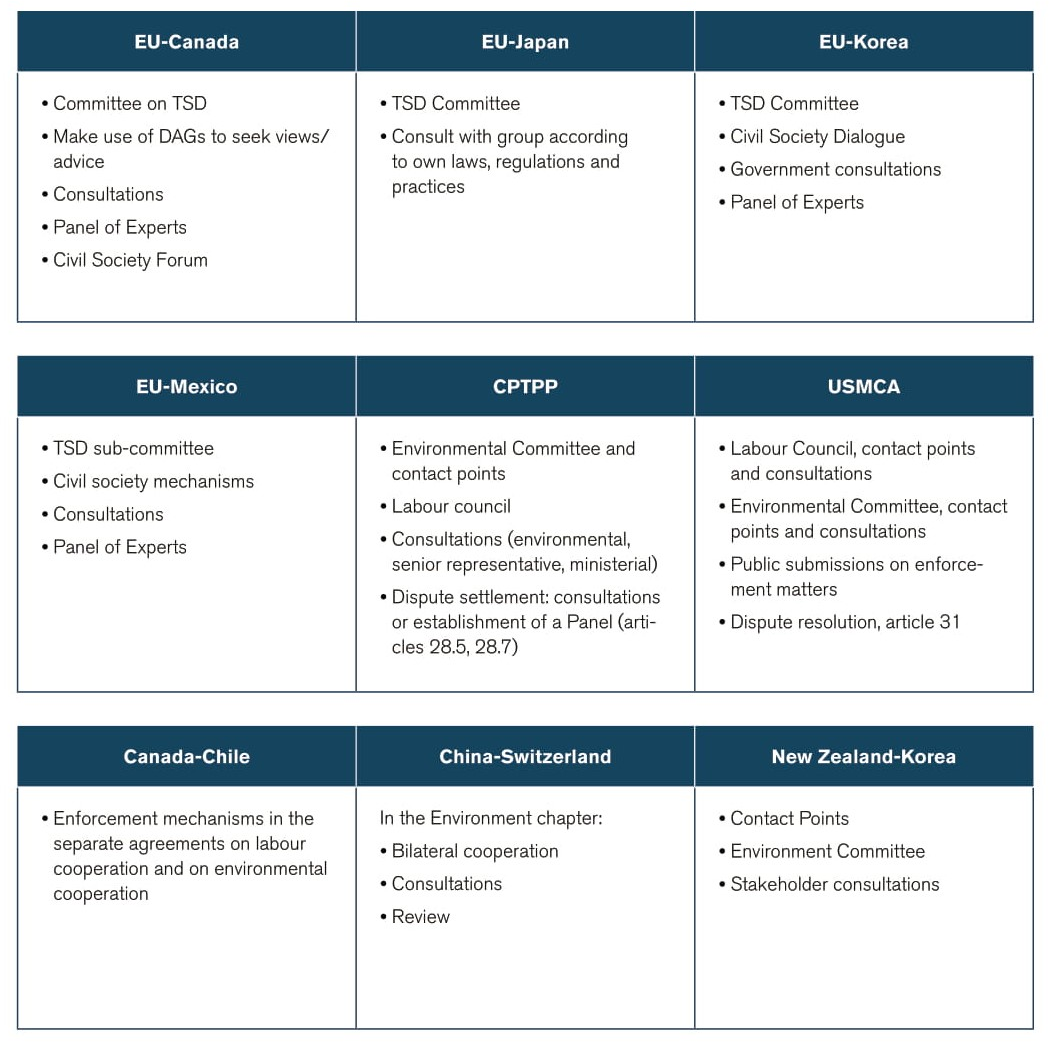

The EU-Korea FTA was the first EU FTA to include a separate TSD Chapter. It set the blueprint for all future TSD chapters and provides institutional mechanisms consisting of three main structures to make sustainability enforceable: an intergovernmental committee overseeing implementation; supporting bodies formed by civil society in the form of ‘domestic advisory groups’ (DAGs) or a broader ‘civil society forum’ (CSF); and additional civil society dialogues that the partner countries wish to host.

DAGs are set up in the EU and in the partner country or countries to provide advice on the implementation of the sustainable development chapters in EU trade agreements. The mechanisms of the DAGs are similar in all FTAs. The addition in the EU-Japan EPA that DAGs must be consulted according to each party’s own rules and practices could lead to a more restrictive approach to DAG mechanisms.[5]

Regarding government to government consultations, the EU-Japan EPA does not explicitly involve civil society, while other FTAs including CETA mention the possibility to seek advice from DAGs, experts or stakeholders. The EU-Mexico FTA even makes this mandatory. When it comes to the panel of experts, the EU-Japan is the only agreement that does not impose to experts to “be independent”, diverging from the usual language found in all other FTAs.

The EU-Japan EPA contains sections on mutual cooperation on trade-related and investment-related aspects of environmental and labour policy. Article 16.12 details an eleven point structure to meet these objectives. These include cooperation on, inter alia, a multilateral level at international organisations, labelling schemes including eco-labels and ethical trade schemes, and trade-related aspects of the international climate change regime, including promotion of low-carbon technologies.

The New Zealand-Korea FTA includes an indicative list of areas of cooperation on the environment (Annex 16A), such as cooperation in international fora, exchange of information on environmental regulations, norms and standards, as well as exchange of opinions of both parties on the relationship between MEAs and international trade rules. Moreover, both sides exchanged a list of environmental priorities with detailed plans of how to fulfil them. A joint environmental committee was created to ensure the progression towards the achievement of these ambitions. A report on success of environmental goals is to be written every three years and must be made public (annex 16).[6] On stakeholder relations both parties are obliged to create mechanisms for domestic stakeholders to provide opinions on the effectiveness of this chapter specifically.

Within Chapter 16, both parties made commitments relating to multilateral agreements, trade favouring the environment, transparency, institutional arrangements, co-operation and consultation. The institutional arrangements (article 16.7) and statements on cooperation (article 16.8 and annex 16A) are of particular interest.

The institutional arrangements clause contains the usual references to contact points. However, article 16.7 also includes the creation of an ‘environment committee’ and ‘stakeholder consultation.’ The committee will: establish an agreed work programme of cooperative activities; oversee and evaluate the co-operative activities; serve as a forum for dialogue on environmental matters of mutual interest; review the operation and outcomes; and take any other action it decides appropriate for the implementation of this chapter.

While the China-Switzerland FTA is not impressive on a global comparison level on the issue of sustainability, it nevertheless shows how FTAs can be used by smaller nations to encourage TSD issues with large, increasingly market-based economies, such as China (especially considering Norway is at present negotiating an FTA with China). Of particular interest is their agreement on cooperation on TBT and SPS. A Sino-Swiss committee was established to monitor seven key areas, such as the coordination of technical cooperation activities, the facilitation of technical consultations and the identification of sectors for enhanced cooperation. As such, the China-Switzerland FTA shows some progress on China tackling the issue of sustainability.[7] The agreement also shows some cooperation by China on sustainability in FTAs.[8]

With regard to the environment, both the CPTPP and the USMCA environment chapters are subject to an enforcement mechanism that includes a three-step consultation process for parties to use in seeking to resolve any disputes that arise. If parties fail to resolve a dispute through consultations, they may use the procedures in the CPTPP Dispute Settlement Chapter with regard to establishment of a panel (article 20.23 CPTPP, article 24.32 USMCA).

Another interesting example is the Canada-Chile Agreement on Environmental Cooperation, which entered into force alongside the Canada-Chile FTA. The Agreement aims to promote environmental protection and sustainable development in both countries. It commits the Parties to effectively enforce their environmental laws and to work cooperatively to protect and enhance the environment and promote sustainable development. It contains remedies that are available to help ensure effective enforcement. Citizens and NGOs can make submissions on enforcement matters asserting that Canada or Chile is failing to effectively enforce its environmental law. These submissions will be considered by an independent Joint Submission Committee and can result in an independent assessment through the preparation of a factual record. A consultation and dispute settlement process is available to the Parties where a persistent pattern of failure to effectively enforce an environmental law is alleged. This process can lead to the creation of an arbitral panel which can recommend a remedial action plan and, in some cases, impose a monetary enforcement assessment.

Article 5 on Government Enforcement Actions is a key article in the Agreement.[9] Parties commit to effectively enforce their environmental laws and regulations through appropriate government action. The article provides 12 examples of appropriate government action such as; appointing and training inspectors; monitoring compliance and investigating suspected violations; seeking voluntary compliance agreements; promoting environmental audits; encouraging mediation and arbitration; using licenses, permits and authorizations; initiating judicial, quasijudicial and administrative enforcement proceedings; providing for search and seizure; and issuing administrative orders. The article specifies that Parties shall ensure that judicial, quasijudicial or administrative proceedings are available to sanction or remedy violations of environmental laws and that sanctions and remedies are appropriate and include compliance agreements, fines, imprisonment, injunctions, closure of facilities and the cost of containing or cleaning up pollution.

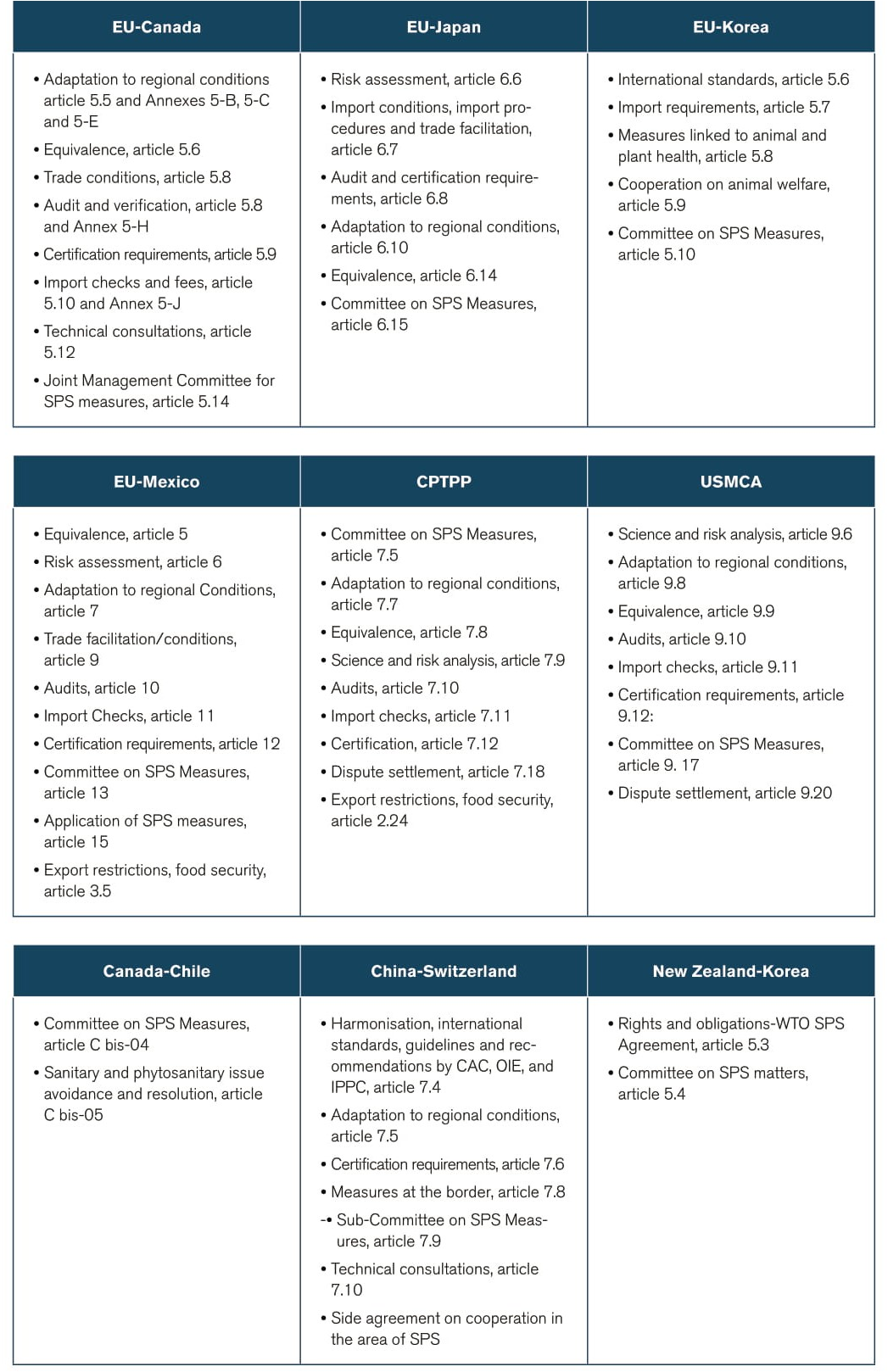

1.6 Market Access

As outlined in the introduction, sustainability provisions can also directly relate to market access conditions. This can be the case for example when it comes to sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures that take the form of specific trade or import conditions. All nine FTAs have a separate SPS Chapter to ensure that trade does not undermine health and safety. The SPS chapters outline market access conditions and the procedures to follow in case the parties disagree on standards and requirements. Reference is made to international and domestic standards, and the agreements include specific provisions on regional conditions, equivalence, audits, certification requirements and import checks.

All agreements make reference to the parties’ rights and obligations under the WTO SPS Agreement and shall take into account relevant international standards, guidelines and recommendations established by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC), the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) or the International Plant Protection Convention (IPPC). When it comes to domestic standards, the FTAs ensure that trade, particularly regarding products of the agri-food sector, is fostered and made faster, by setting common sanitary standards, facilitating transit of goods through customs and by reducing costs due to export procedures and certifications. Provisions on the adaptation to regional conditions further foster predictability of trade. More specifically, provisions regarding import conditions, risk analysis and certifications are present in the majority of the agreements. The aim is to simplify the procedures, while ensuring the fulfilment of all SPS measures and the exchange of relevant information between the parties. When it comes to imposing certification requirements, this is done only in accordance with international standards and in the least disruptive way possible. For example, to avoid imposing unnecessary burden, FTAs include provisions on developing a model certificate between the parties or electronic certificates and other technologies to facilitate trade (USMCA, CPTPP and EU-Mexico).

As far as adaptation to regional conditions is concerned, these provisions in the FTAs contain a variety of measures, including zoning, compartmentalisation, recognition of pest- or disease-free areas, and areas of low pest or disease prevalence. Such provisions are crucial, not only because they build confidence between the parties, but also in order to ensure adequate conditions for plant and animal safety, health and for the protection of relevant animal and plant products, which is of utmost importance for successful trade in the sector of food and agriculture. CETA provides more details regarding adaptation to regional conditions, as it lists the diseases on which zoning applies in Annex 5-B, includes principles and guidelines to recognise regional conditions in Annex 5-C and outlines additional guarantees and special conditions in Annex 5-E.

Provisions on import requirements, checks and fees in the majority of the FTAs (CETA, EU-Japan, EU-Korea, CPTPP, USMCA, EU-Mexico) aim at ensuring solutions that allow for an appropriate level of SPS protection in accordance with international standards, while also being practicable and less trade-restrictive. This is achieved, for example, by avoiding unnecessary delays and outlining procedures for cases of non-compliance (EU-Mexico, article 11). In CETA, principles and guidelines for import checks and fees are set out in Annex 5-J.

Furthermore, to enhance confidence in the implementation of the SPS Chapter and determine the exporting party’s ability to provide assurances that SPS measures are met, the possibility is given to the importing party to audit the exporting party’s relevant authorities and inspection systems. Audits are included in all SPS chapters except for EU-Korea, Canada-Chile, China-Switzerland and New Zealand-Korea. In particular, the relevant article in CETA provides the option of an audit or verification and includes all principles and guidelines agreed by the parties to conduct an audit in its Annex 5-H.

Except for the EU-South Korea, New Zealand-Korea, China-Switzerland and Canada-Chile FTA, all other FTAs contain an article on equivalence. Equivalence means that the importing Party shall recognise SPS measures of the exporting party as equivalent to its own, thereby making trade faster and simpler. In the majority of the FTAs, a party recognises equivalence if the other party “objectively demonstrates” that the measure results in an appropriate level of protection. The articles outline the process of assessing, determining, changing and maintaining equivalence of SPS measures.

A specific characteristic of the CPTPP and USMCA is the provision “Science and Risk Analysis”, which aims to ensure that SPS measures are based on scientific principles. If relevant scientific evidence is insufficient, an SPS measure is to be adopted on a provisional basis. Parties may establish or maintain an approval procedure that requires a risk analysis to be conducted before the party grants a product access to its market. SPS measures should not discriminate between the parties or constitute a disguised restriction on trade. Relevant risk assessment procedures shall be undertaken in accordance with the provisions of this article upon request and should not be more trade restrictive than required to achieve the necessary level of protection. Risk assessment is also included in the EU-Japan EPA and the EU-Mexico GA.

Cooperation and dispute settlement mechanisms are of high importance for trade in the agri-food sector, as they render trade more secure and predictable. When it comes to cooperation, the SPS chapters of the agreements include the creation of a committee on SPS measures (or sub-committee in the case of the Sino-Swiss FTA[10]), which serves as the institutional framework for implementing the SPS Chapter, as well as a forum for resolving issues and enhancing cooperation on all SPS related issues. The Canada-Chile FTA includes Article C bis-05 on “Sanitary and Phytosanitary Issue Avoidance and Resolution”, in order to ensure that any arising issue is resolved expeditiously through all reasonable options, such as meeting in person or using technological means and opportunities that may arise in international fora. Interestingly, regarding dispute settlement, only the CPTPP and the USMCA, in their Articles 7.18 and 9.19-9.20 respectively, provide recourse to dispute settlement for matters arising under the SPS Chapter. Moreover, both CPTPP and USMCA include the creation of a panel that should seek advice from experts in case a dispute involves scientific or technical issues. In the USMCA, the parties shall first seek to resolve any issue through technical consultations before initiating a dispute settlement procedure.

Finally, apart from the SPS chapter, export restrictions related to agriculture and food safety (in addition to conditions set out in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture) can be found in the chapters of the FTAs dedicated to agriculture, such as in article 2.24 of the CPTPP or article 3.5 of the USMCA.

1.7 Concluding Remarks

The FTAs analysed include specific market access conditions that relate to sustainability provisions. Such market access conditions are mainly related to SPS measures, but can also be linked to provisions on agriculture and food safety. The relevant SPS chapters outline provisions related to protection of human, animal and plant life or health. The chapters build on existing commitments under the WTO SPS Agreement and make reference to relevant international standards, guidelines and recommendations established by the CAC, OIE, and the relevant international regional organisations operating within the framework of the IPPC.

When it comes to domestic standards or disagreements related to the levels of SPS protection, SPS chapters provide for cooperation measures and support work on equivalence, import conditions and checks, regional conditions and harmonization, audit and verification procedures, as well as certification requirements. A Committee on SPS Measures is established, which is in charge of implementing the SPS chapter and providing a forum to discuss and resolve relevant issues. All the above provisions facilitate trade, enhance its predictability and speed, and build confidence between the parties while protecting plant and animal products ‒ a crucial element for trade in the agri-food sector.

In addition to these market access conditions, more general sustainable development provisions are integrated in the FTAs analysed. They also include dedicated mechanisms to deepen commitments made and to enhance cooperation and enforcement, for example through committees or advisory groups. The forms in which the FTAs include sustainability provisions are through dedicated chapters, preambular references, specific paragraphs in the body of the agreement, as well as in side agreements or annexes.

The dedicated chapters on issues of sustainability in the FTAs analysed generally include comprehensive sustainability provisions. However, they often only establish best endeavour commitments and essentially reiterate existing commitments. For example, EU agreements often use non-binding language in the TSD chapters and do not provide explicit prohibitions that are enforceable with concrete sanctions for violation.

Many EU agreements rely on new forms of ad hoc dispute settlement such as state-to-state consultations, the use of advisory bodies or expert panels, often mainly aimed at reaching a mutually agreed solution. This is supported by institutional mechanisms that promote dialogue between the party’s civil society groups. In contrast, especially many US agreements since NAFTA have been characterised by a substantive inclusion of sustainable development provisions in their general dispute settlement mechanisms, which is also the case for USMCA. Other agreements including those of the EU exclude sustainable development chapters from such a dispute settlement mechanism. Accordingly, a party cannot effectively sanction another party for violations of commitments on sustainability in these agreements.

In addition to this aspect of dispute settlement, there is no essential elements clause in the FTAs analysed that would make trade liberalisation conditional on compliance to provisions on sustainable development. There is also no explicit non-execution clause in these FTAs. Such a clause would allow for a suspension or termination of the agreements if a party does not fulfil its obligations under sustainable development provisions.

The FTAs also make substantive reference to MEAs. There are about 20 MEAs that contain provisions related to trade. Such specific trade obligations can prohibit or restrict trade in certain products. However, enforcement provisions in these MEAs are often weak, for example only relying on monitoring and reporting of non-compliance by private agents such as NGOs.

[1] According to the UNEP Trade and Environment Briefing: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/25950/sustainable_agriculture.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[2] See: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2018/april/tradoc_156791.pdf

[3] See: https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/fact-sheets/modernizing

[4] See: https://www.transportenvironment.org/sites/te/files/publications/2018_09_TSD_analysis_0.pdf

[5] See: p. 29: https://www.transportenvironment.org/sites/te/files/publications/2018_09_TSD_analysis_0.pdf

[6] See: https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements-in-force/nz-korea-free-trade-agreement/text-of-the-new-zealand-korea-fta-agreement/

[7] See: https://www.seco.admin.ch/dam/seco/en/dokumente/Aussenwirtschaft/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen/Freihandelsabkommen/Partner%20weltweit/China/Abkommenstexte/Texts%20in%20English/Agreement%20on%20Cooperation%20in%20the%20Area%20of%20TBT%20and%20SPS.pdf.download.pdf/Agreement%20on%20Cooperation%20in%20the%20Area%20of%20TBT%20and%20SPS.pdf#page=16

[8] See: https://www.seco.admin.ch/dam/seco/en/dokumente/Aussenwirtschaft/Wirtschaftsbeziehungen/Freihandelsabkommen/Partner%20weltweit/China/Abkommenstexte/Texts%20in%20English/Switzerland-China%20FTA%20-%20Main%20Agreement.pdf.download.pdf/Switzerland-China%20FTA%20-%20Main%20Agreement.pdf

[9] https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/corporate/international-affairs/partnerships-countries-regions/latin-america-caribbean/canada-chile-environmental-agreement/analysis-chile-agreement-environmental-cooperation/chapter-2.html.

[10] The work of the Sub-Committee is outlined in the Side-agreement on cooperation in the area of SPS.

2. Analysis of Key Sustainability Standards and Regulatory Cooperation Agreements

2.1 Introduction

This section analyses how to design domestic sustainability standards so that they can support trade policy in promoting sustainable agriculture internationally. It is not sufficient that businesses/producers only apply advanced sustainability practices. It is also necessary that the domestic law and relevant rules and regulations actually reflect these high practices so that reference to these standards can be made in international agreements. In addition, domestic standards need to be raised to ensure that high sustainability practices apply to all, both domestic and foreign producers. Accordingly, raising standards also ensures that relevant trade policy provisions do not result in market access discrimination against foreign producers.

Therefore, the aim of this analysis is to prompt the raising of existing sustainability standards in Norway, so that they meet the high and advanced practices already in place and serve as a tool for trade policy promotion of sustainability. To achieve this, we will examine the relevant domestic sustainability standards in the following areas: Limited use of medicines in livestock production; Limited use of chemicals and pesticides; High Animal welfare; Protection of biological diversity; and social aspects including worker’s rights. Each of the above areas highlights two levels of analysis: on the one hand, inspection mechanisms in place both at the border/customs’ level and at inspection agencies’ level; and on the other hand, qualification/certification requirements and processes, including the role of relevant institutions and authorities.

The analysis lays a focus on two points related to the raising of domestic standards. Firstly, it will demonstrate and discuss opportunities resulting from the raised standards, both for Norway and internationally. Secondly, it will present constraints related to the raising of standards, including the need to employ political will, to leverage relevant bodies and institutions, to raise awareness and organise outreach activities in order to create or support a political trend that will lead to the raising of domestic standards. To this end, we conduct a comparison with other countries and their domestic sustainability standards, which will provide insights into opportunities and constraints internationally. The process other countries followed to overcome these constraints will be elaborated to provide some useful insights for the situation in Norway. In addition, background information on important actors in the fields of domestic sustainability standards and agriculture in Norway is presented in Annex 2.

Finally, our analysis will highlight, in addition to domestic standards, the work of some countries with regulatory cooperation instruments. These instruments take the form of bilateral agreements on veterinary standards, inspections or market approval arrangements. They are concluded independently of FTAs or as side-agreements to them. Such instruments have been identified and will be included in the relevant thematic chapters below. Two of these instruments of regulatory cooperation are broader and cover several of the thematic areas: mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) and the Australia-China Agricultural Cooperation Agreement (ACACA). For more background on these two instruments, see Annex 2.

2.2 Limited Use of Medicines in Livestock Production

Norway’s efforts concerning the use of medicines in livestock production have focused on the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR).[1]

2.2.1 International level

The WHO published a global action plan on AMR in 2015, which sets out five strategic objectives: to improve awareness and understanding of antimicrobial resistance; to strengthen knowledge through surveillance and research; to reduce the incidence of infection; to optimize the use of antimicrobial agents; and develop the economic case for sustainable investment that takes account of the needs of all countries, and increase investment in new medicines, diagnostic tools, vaccines and other interventions.

At the World Health Assembly in 2015, all UN Member States endorsed the Global Action Plan on AMR and adopted a Resolution recognising the importance of tackling AMR through a “One Health” approach, involving different actors and sectors, and committing to develop by 2017, national action plans (NAPs) on AMR aligned with the Global Action Plan (see Annex 2 for more information). Council Conclusions on a One Health approach to combat AMR, adopted in June 2016, reiterated this commitment and elaborated on some aspects which NAPs on AMR, adapted to national contexts, could include. In spite of the recent momentum, enhanced political will and strengthened policy commitment towards a more coordinated and multisectoral approach to addressing AMR, progress on the development and more importantly, the implementation of national plans at local level has not been optimal. More recently, the WHO included AMR among the top 10-list of global health threats for 2019.[2]

2.2.2 Norway

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority (NFSA) has overall responsibility for ensuring compliance with the regulations throughout the entire food production chain. Through the NFSA’s monitoring and control programs (OK programs), antibiotic resistance in animals and food is surveyed.[3] In June 2017 Norway launched an action plan in line with the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) 2015 directive on the matter. The plan was developed by a working group with members from the different livestock organisations of Europe.

Norway’s history at the forefront of antimicrobial usage was detailed in the study. In a 2014 report from the European Medicines Agency (EMA), Norway was listed, together with Sweden and Iceland, among the countries in Europe that have the lowest antimicrobial usage per unit of biomass produced in their animal production. Factors important in this statistic are the prohibition on antimicrobials as growth promoters, the banning of their use for routine prevention of infection, and carefully organised breeding systems through the NormVet monitoring programme. Equally significant is the national regulation that forbids veterinarians from profiting from selling antimicrobials and other drugs (decoupling). Thus, there is no economic incentive to prescribe antimicrobials, as there is in other countries.

In contrast to the situation in many countries in the southern and eastern Europe, the use of antibiotics in Norway is low.[4] The prescribing patterns are favourable, and antibiotics can’t be bought unless prescribed by doctors, veterinarians or fish health graduates. The Norwegian Government has adopted a national strategy against AMR for the period 2015–2020[5].

The 2018 NORM-VET report[6] shows that the Norwegian government’s goal to reduce antibiotic use in food-producing land animals by 10% between 2013 and 2020 has already been reached. The use of antibiotics in farmed fish remains low. Occurrence of antibiotic resistant bacteria is affected by what happens in both Norway and the rest of the world. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria from animals such as cattle, pigs and horses and in food are also low. In 2017, a total of 5528 kilos of antibiotics were used for food-producing land animals. This is a drop of around 10% compared with 2013 and around 40% since 1995. We can safely say the Norwegian poultry breeding population is most likely free from MRSA – staphylococcus bacteria that has developed resistance to a type of penicillin, beta-lactams, which is an important group of antibacterial agents.

2.2.2.1 Import and export

Import: All foodstuffs imported into Norway must comply with Norwegian food law. The importer must be registered as an importer in the Norwegian Food Safety Authority’s form services (MATS) and is responsible for ensuring that the food is safe for health, and that content and labelling are in accordance with Norwegian rules. If this is not the case, the foodstuffs may be imported and traded. There are different rules for import depending on whether they come from an EU / EEA country or from countries outside the EEA area (for more information on the EEA, see Annex 2). Some trade goods are registered in a common EU database called TRACES (TRAde Control and Expert System).

Export: Norwegian food, drinking water, animals, feed and waste products are exported to many countries around the world. The Norwegian Food Safety Authority is a supervisory body that shall ensure that food products exported out of the country are safe and produced in a safe environment according to Norwegian regulations, and in this connection the Norwegian Food Safety Authority issues certificates and declarations for exports out of Norway.[7]

2.2.3 Comparison with other countries

Many countries have taken action on AMR following the WHO’s 2015 report.[8] Japan planned to cut antibiotic use by 2/3rds in 2016-20 while Korea established an antimicrobial resistance surveillance system (KOR-Glass) in 2016. Canada’s actions are perhaps the most significant though, as they have implemented a series of regulatory changes under SOR/2017-76 May 5, 2017.

For an overview of the AMR standards in place in 31 countries (EU Member States, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland), a recent study of the European Public Health Alliance can be consulted.[9] Most countries do have a NAP in place or have initiated the process for its development. In fact, of the 31 countries analysed in this study, 74% have developed and/or implemented a NAP or a similar initiative to tackle AMR. However, Member States are at very different stages in terms of developing and implementing NAPs or similar initiatives to combat AMR. It is striking that most One Health NAPs are found in Northern and Central Europe, where AMR prevalence is generally lower than the rates observed in Eastern and Southern European countries, which often face considerable healthcare systems challenges and lack of sustained financing. There are also considerable variations with regard to the comprehensiveness and the One Health approach reflected in the NAPs in place. In fact, at the time of this analysis, only 51% of the countries analysed could be considered as having action plans or national programmes or strategies that follow a One Health approach. In fact, whilst acknowledging the One Health concept, some NAPs do not appear to follow a truly One Health approach and still address AMR in different fields separately.

According to the OECD, trade and agriculture is among the sectors of the wider economy that is most likely to be affected by AMR.[10] For example, in 2015 chicken sales in Norway dropped by 20% (for some distributors) following the news that a resistant strain of Escherichia coli (E. coli) was found in chicken meat. Similarly, poultry consumption dropped by about 20-25% in several Asian countries, including Singapore, China and Thailand during the 2003 avian flu outbreak (Bánáti, 2011). In respect to veterinary and agricultural practices, Japan continuously conducts and reinforces risk management measures based on the risk analysis framework; Canada and the European Union plan to strengthen the regulatory framework.

Japan’s[11] response to rising rates of AMR in the livestock sector is based on a three-pronged approach: First, Japan has based the development of specific policies and risk management measures in the area taking as reference point the risk analysis principles mentioned in the code of practice developed by the Codex Alimentarius Commission (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2012). Risk management measures are continuously conducted and reinforced in accordance with the risk level.

Second, in response to international concern about the impact of AMR on public health, Japan has established in 1999 the Japanese Veterinary Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring system (JVARM). JVARM monitors levels of AMR in zoonotic and animal pathogenic bacteria and monitors quantities of AMTs used in animals. JVARM collaborates with JANIS (Japan Nosocomial Infectious Surveillance: AMR surveillance for human health sector). Finally, Japan has published the Prudent Use Guidelines for veterinary AMTs (Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, 2013).[12]

One-health features strongly in Germany’s plans, and approaches include addressing AMR issues such as waste water management through continuation of the interministerial AMR working group, supporting research on zoonoses through renewed research agreements between Ministries. Further plans entail, various monitoring activities, including monitoring resistance of zoonoses beyond those obligatory by the EU, expanding and standardising laboratory capacities, implementing laws on use of AMTs in animals, and continued antibiotic consumption registration amongst veterinary doctors. Developing further legislation on use of antibiotics amongst animals, early disruption of transmission through improved animal husbandry and vaccination are also included. Regional programmes are to be supported and flagship models are to be promoted, as well as targeting food-chains by determining efficacy of control programmes and developing hygiene criteria and research on hygiene measures in food-chains. Finally, there are also extensive research and development plans, focused on preventing emergence of resistance and prevention of transmission.

2.3 Limited Use of Chemicals and Pesticides

2.3.1 International level

Pesticides use is influenced by the WHO, which, in collaboration with FAO, is responsible for assessing the risks to humans of pesticides and for recommending adequate protections. Note that this international guidance and standards on pesticieds are limited to direct exposure and residues in food products.

Risk assessments for pesticide residues in food are conducted by an independent, international expert scientific group, the Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues (JMPR). These assessments are based on all of the data submitted for national registrations of pesticides worldwide as well as all scientific studies published in peer-reviewed journals. After assessing the level of risk, the JMPR establishes limits for safe intake to ensure that the amount of pesticide residue people are exposed to through eating food over their lifetime will not result in adverse health effects. These acceptable daily intakes are used by governments and international risk managers, such as the Codex Alimentarius Commission (the intergovernmental standards-setting body for food), to establish maximum residue limits (MRLs) for pesticides in food. Codex standards are the reference for the international trade in food, so that consumers everywhere can be confident that the food they buy meets the agreed standards for safety and quality, no matter where it was produced. Currently, there are Codex standards for more than 100 different pesticides. WHO and FAO have jointly developed an International Code of Conduct on Pesticide Management. It guides government regulators, the private sector, civil society, and other stakeholders on best practices in managing pesticides throughout their lifecycle – from production to disposal.

On the EU-level, the Biocidal Products Regulation (BPR, Regulation (EU) 528/2012) concerns the placing on the market and use of biocidal products, which are used to protect humans, animals, materials or articles against harmful organisms like pests or bacteria, by the action of the active substances contained in the biocidal product. This regulation aims to improve the functioning of the biocidal products market in the EU, while ensuring a high level of protection for humans and the environment.

3.3.2 Norway