Reforming Services: What Policies Warrant Attention?

Published By: Erik van der Marel

Research Areas: Five Freedoms Services

Summary

Economic growth in the European Union has been low for more than a decade now. While some of the poor performance can be explained by the crisis, the sustained low growth is to a very large extent the consequence of sluggish productivity performance. Productivity is above all an indicator of a society’s long-term welfare and measures how effective we are at using our scarce resources in the economy. Therefore, it is critically important – and any reform effort should focus on boosting growth through higher productivity growth.

The recent Services Package – a set of proposals to support Europe’s services sector – is a case in point. It has long been established that rates of productivity growth in Europe’s services sector trails the rates in the United States and other comparable economies. As the economy increasingly gets dependent on services, the risk for Europe is that the natural economic transformation will weigh down our productivity growth.

Obviously, any services reform aiming at delivering growth should start from the policy barriers that hold back growth and a greater degree of economic dynamism. Few, however, do. The type of restrictive policy measures in the EU vary across different services sectors – and, hence, what is the right policy priority for one country may not be right for the other. Yet, when looking at some services policy developments in Europe more closely, some patterns do become clear. Those should now be the focus of policy reform.

Barriers to Entry – and Barriers to Operation

Generally, domestic regulatory policy barriers in services can be broken down into those that affect entry of firms into a market and other policy barriers that have an impact on the operations of firm activity. The two policies are connected, of course, and have a distinctive impact on productivity.

Barriers to entry restrict foreign and domestic service providers from bringing competition to the market. If entry barriers are high, domestic incumbents will be sheltered from competition and less incentivized to perform better. Eventually, this leads to higher prices for European consumers and businesses using services. Barriers to operations, on the other hand, are barriers that firms encounter after entry has taken place.

Previous studies have shown that in order to generate growth, the EU’s rate of new firms entering the markets does not substantially differ from the United States (i.e. Bertelsman et al, 2003). What differs is what happens next: firms in the EU are less likely to expand quickly and have greater difficulties pushing out less-productive firms from the market (OECD, 2016). Hence, barriers to operations are essential in the EU or what could be called barriers to firm growth.

This is important. To generate growth in Europe, there needs to be much more work on the regulatory burden – the regulations that prevent the well-known Schumpeterian dynamic of ‘creative destruction’. Indeed, in the EU a great deal of potential productivity growth would come from services reform in the post-entry phase. A recent study by Van der Marel et al (2016), using data from millions of European firms, shows that in order to raise productivity growth in services markets it is the removal of conduct barriers that really matters. This does not mean, however, that reforms on operational restrictions can be successfully pursued without reforming entry barriers. As a matter of fact, work still needs to be done to ease market-entry for firms, particularly in professional services; an area that the Services Package tries to tackle.

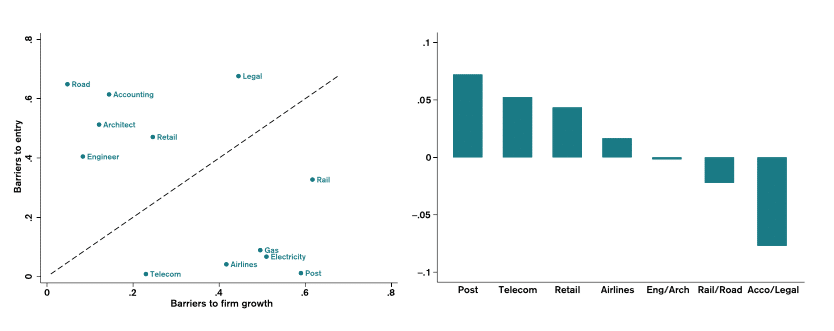

This can be seen in Figure 1 below. The left-hand panel splits up the two types of regulatory barriers into entry barriers on the vertical axis and barriers to firm growth, i.e. operational barriers, on the horizontal axis. Services sectors placed in the upper-left corner of this figure show a relatively high share of entry barriers in their markets compared to their operational barriers. It means that entry barriers in these services are currently greater than their operational barriers. Conversely, sectors positioned in the lower-right corner of the figure still have a relatively high share of operational barriers in their markets, inhibiting firm growth compared to their level of entry barriers.

The figure shows that many professional services such as engineering, legal, accounting and architectural services still have high entry barriers in place. Many domestic and foreign firms are therefore still prevented from reinforcing competition in their sectors, and these restrictions ultimately reduce consumer choice and the positive effects of a true single European services market. Other services such as transportation services and utilities have relatively lower barriers to entry, but comparatively higher conduct barriers.

Figure 1: Barriers to entry vs barriers to firm growth and productivity in services (2013-2014)

Source: OECD; van der Marel et al. (2016). Productivity figures are TFP based on Ackerberg et al. (2015)[1]

These categories of services regulation have a knock-on effect on productivity in the EU. Detailed studies such as Arnold et al. (2011) and Van der Marel et al. (2016) have shown how they depress productivity in EU countries.[2] This can also be seen in the right-hand panel of Figure 1 in which the average productivity of each sector is shown in order of importance. It shows that postal, telecoms, retail and airline services all have positive growth effects. These are exactly the sectors which already have experienced lower entry barriers for firms. However, their growth is still below their potential and their productivity levels are still modest. Reducing these sectors’ post-entry barriers of firm growth and expansion will therefore increase the potential to create further productivity growth.[3]

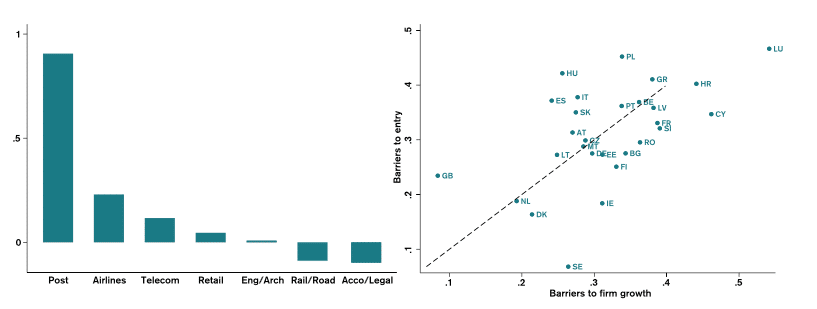

There is a different story for professional services – and rail and road services. These sectors have seen negative productivity growth in recent years, underlying the fact that competitive forces – increasing the level of productivity – remain untapped. This is most likely due to the high entry barriers in these sectors. The results of these productivity figures are robust to alternative productivity measures. There are several ways in which productivity can be computed – and they could provide different results. Yet, using another commonly used methodology of calculating productivity provides the same sectoral ranking as can be seen in the left-hand panel of Figure 2.

Figure 2: Productivity in services and barriers to entry vs barriers to firm growth (2013-2014)

Source: OECD; van der Marel et al. (2016). Productivity figures are TFP based on Olley and Pakes (1996)

In addition, the right-hand panel of Figure 2 points out which countries, across all services sectors, have relatively high entry barriers or conduct barriers. In a similar manner, countries which are more placed towards the vertical axis have relatively high entry barriers, whilst countries which are more located towards the horizontal axis have a relatively large share of regulatory policies inhibiting firm growth. Austria, Poland and Italy, for instance, still have services barriers in place which prohibits firms from entering, whilst other countries such as Finland, Romania and France have relatively high restrictions on firm expansion.

[1] The firm-level TFP measure are weighted by firm-size in the aggregation process across each services sector.

[2] Country-specific studies using firm-level data show this knock-on effect outside the EU as well such as Arnold et al. (2015). Studies using industry-level data showing this effect for OECD economies are Barone and Cingano (2011) and Bourlès et al. (2013).

[3] The only exception is retail services which still has relatively high entry barriers. However, this sector’s measurement of productivity is difficult to measure and therefore needs to be taken with some margin of error.

Going for Growth – Necessary Policy Reforms

What does this mean for the Services Package? The Services Package is a set of measures that aims at making it easier for companies and professionals to start and expand their services, particularly in professional services such as lawyers, accountants and engineers. The EU does not de- or re-regulate existing rules in these services but ensures that these rules are applied in a good way through better regulatory practices that are not overly burdensome or out-of-date.

One of the instruments the EU announced in the Services Package is the proportionality test for (professional) services. This test assesses precisely whether new legislations and changes to existing rules in services are adhering to these conditions of not being overly burdensome or outdated. For professional services, this test should therefore specifically pay attention to barriers to entry for outsiders willing to come into the market. The European Commission is aware of that aspect since the long list of restrictions that it takes up in the mutual evaluation process has many entry restrictions.

However, the EU should not lose sight of conduct barriers or the de facto barriers to firm growth. Although they seem to be less prevalent in professional services than other services (as Figure 1 shows), some services professions such as legal services still have many conduct barriers in place.[1] It is important to tackle these restrictions as barriers to firm growth form a set of second-generation barriers that over time reduces the long-term dynamic effects of creative destruction and prevents the EU to raise its productivity.

Moreover, as the focus in the Services Package is mostly on entry barriers, the EU should be attentive to Member States that are substituting entry barriers with other murky rules and regulations, outside the scope of the proportionality test. They may just be another form of barriers of conduct – leading to a shift from entry to post-entry barriers. This is important because the rate of regulatory change in professional services is high, creating many opportunities for the regulations to move in the wrong direction. Without a strong proportionality test, there is a risk of regulations sliding into new “hidden” barriers that cover operational restrictions and preventing long-term productivity effects even if entry barriers are lowered.[2]

On top of that, the EU has introduced an improved notification procedure and a guidance report on specific reforms that Member States need to implement for each profession. These efforts are laudable as they provide transparency and pressure on governments to continue their reform process, which the previous notification procedure did not – or, in the words of the Commission, “did not adequately contributed to a correct and full implementation of the Services Directive” (European Commission, 2017a; 2017b).

This is an issue of concern. Although some Member States do not want to reform, there are countries that simply have limited regulatory capacity and are not capable of organizing regulation in a way that reinforces the benefits from reforming services markets. That is, governments and regulators need expertise, resources and the right governance structure to undertake regulatory changes in their systems, for example by fine-tuning complementary rules in competition policy, providing adjustment mechanisms to compensate losers, or monitoring firm behavior in services markets and the economic impact of reforms.[3]

This goes well-beyond any Directive and rather focuses on how well-equipped regulatory bodies and governments are in terms of monetary resources, regulatory expertise and overall regulatory management practices. These items are complementary to reducing or reforming regulatory barriers. If the Services Package aims at creating good and better regulatory practices, the EU needs to take this aspect seriously.

Some Member States will not be able to reform services markets because of these limitations. While the European Commission observes that the new notification procedure does not create any disproportionate new costs for Member States – they are already obliged to notify measures under the Services Directive – it neglects the question of how public authorities have to deal with post-services market reforms when knowledge, expertise and regulatory management are required rather than new rules.

An OECD indicator on regulatory management in services – that measures the governance of the bodies that design, implement and enforce these regulations in services – provides further insights.[4] It shows that some countries such as Italy, the UK and Germany have good performance. Other countries such as Austria, Denmark and Estonia score well below the OECD average. Scores vary according to sectors and sub-components, but an interesting fact is that some EU countries that otherwise score well in their regulatory policies score bad in their regulatory governance.

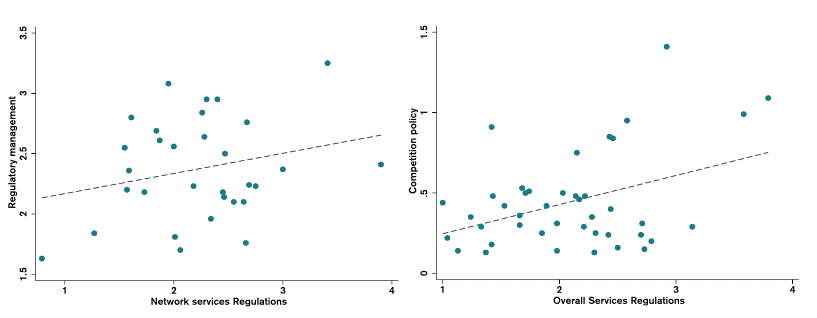

Yet, there is generally a systematic relationship between regulatory policies and regulatory governance as shown in the left-hand panel of Figure 3. The vertical axis shows the score of regulatory management from 0 (the most effective governance structure) to 6 (the least effective governance structure) in services.[5] The horizonal axis illustrates the level or regulatory restrictions in services. The figure shows indeed that countries with higher regulatory barriers in services are also the ones with least effective governance structures to tackle services reforms.

Figure 3: Regulatory governance policies in services and services reforms (2013)

Source: OECD; author’s calculations.

Another indicator, from the World Bank, showing the economy-wide regulatory quality and government effectiveness of countries, exhibits a performance where the Northern EU block scores well whilst the Southern and Eastern blocks together score lower than expected. Whatever the right ranking, the main point is that countries vary in their ability to govern regulations for services markets.

This governance factor is not restricted to regulatory management or regulatory quality in services alone. There are other governance policies for how services markets are organized that are important. One is related to competition policy. It is necessarily not about the competition rules per se, but – again – how policies are pursued within the framework, for example the effectiveness, soundness and transparency of competition-policy institutions, and the strength and scope of competition regimes.

Another indicator from the OECD precisely measures this aspect of competition governance and is used in the right-hand panel of Figure 3.[6] This score is shown on the vertical axis and varies between a scale of 0 and 6 (from the most to the least effective competition regime). On the horizontal axis, the level or regulatory restrictions in services is shown. Here, too, the panel points out that there are complementarities between the governance of competition regimes, i.e. the institutional set-up of effective competition structures, and services barriers reform. Countries which have less effective competition regimes also show higher regulatory barriers in services.

[1] High conduct barriers for the legal profession also became visible in its EU Regulated Professions Database.

[2] A study by the World Bank (2016) and van der Marel et al. (2016) pointed out that precisely in the EU barriers on the conduct of the firms have strongest and most important economic impact on services generally, including non-professional services.

[3] As European Commission (2017b) states: “The [previous] mutual evolution process revealed that regulatory decisions are currently not always based on sound and objective analysis or carried out in an open and transparent matter”.

[4] Professional services are excluded from this indicator but nonetheless provides a good state of regulatory play of the institutional setting for each country regarding the entire services sector.

[5] See Koske et al. (2016) for further explanations on this indicator.

[6] See Alemani et al. (2013) for further explanations of this indicator.

Conclusion

The Single Market for services is still not complete. Many countries in the EU still uphold regulatory barriers in services whilst some already show a much lower level of services restrictions in their markets. As the EU has a real productivity problem, it is important to focus more precisely on the types of barriers in each services market. Entry barriers is an area that allows for a first opportunity of introducing more competition in services, unleashing pressure on providers to become more efficient. Reforming barriers on operations is another opportunity.

In fact, reducing barriers on operations is important for the EU’s long-term growth. These are second-generation barriers which in some services markets are hard to handle. Reducing them create sustained dynamism in services by allowing firms to expand and grow, reaping further productivity gains that will eventually lead to higher economic growth. While barriers in services are important, they are only half of the story. A services reform package should also look at how capable and equipped member states are in governing services markets during and after the reform process.

Some countries show a greater capacity to deal with new regulations while others are less capable to do so. This varying degree of good regulatory governance in services across countries has an additional impact of how well these countries can generate productivity through services reform. That includes regulatory propositions by the EU. Regulatory governance and regulatory reform are closely connected with each other. Therefore, the EU needs to pay far more attention to how services markets are governed.