No, China Does Not Make Everything!

Published By: David Henig Anna Guildea

Research Areas: New Globalisation WTO and Globalisation

Summary

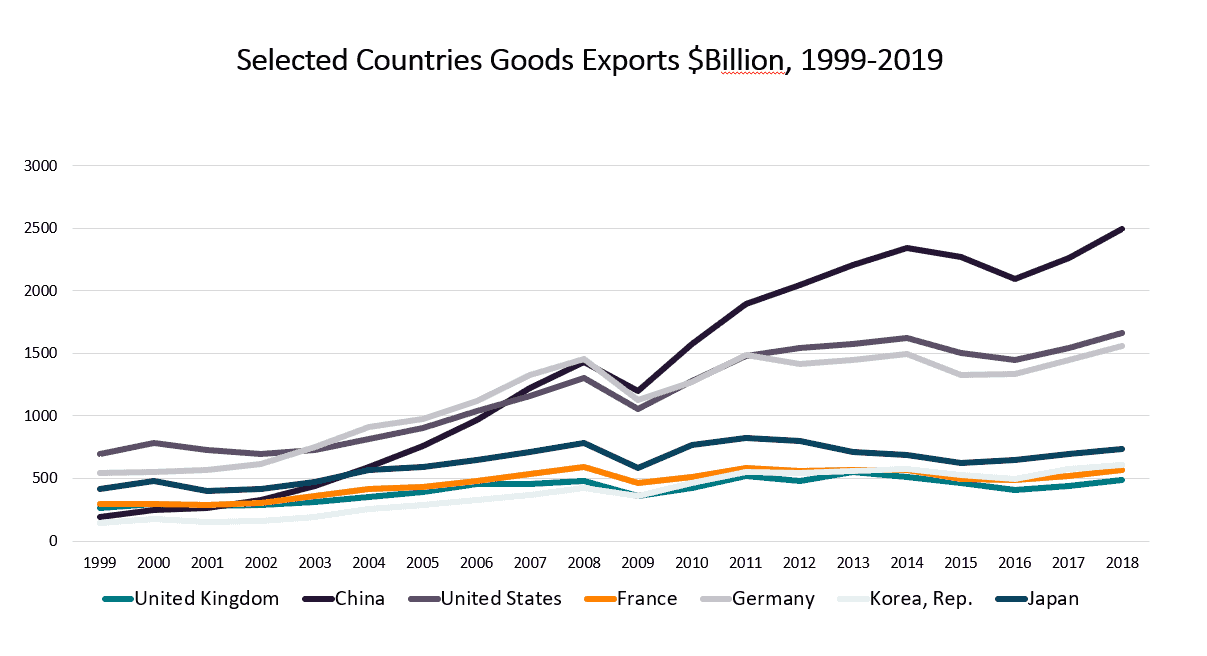

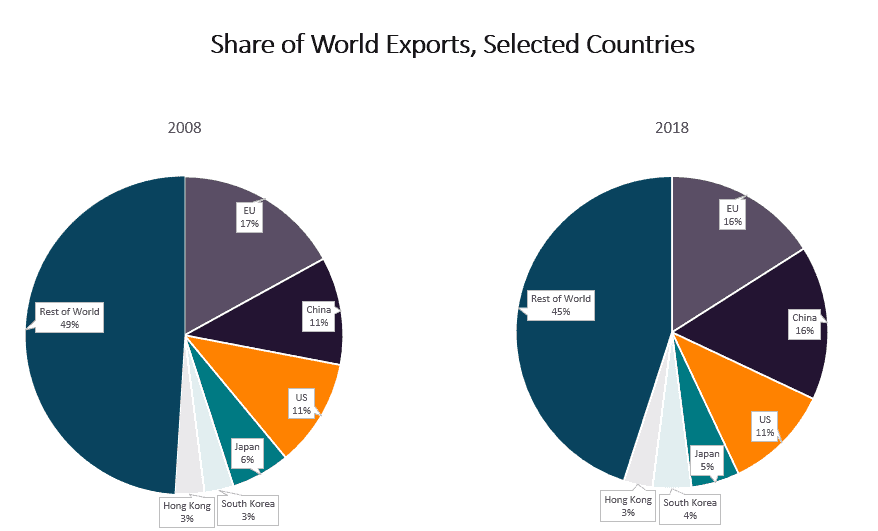

China is now the world’s leading manufacturer, with goods exports rising from $63 billion in 1990 to $2.5 trillion in 2018. The popular assumption is that everything is now made in China, and that falling manufacturing employment in the EU and US is due to this.

The assumption is wrong. China is the world’s largest goods exporter, but other countries have also experienced increases. One reason is that China is also the world’s second largest importer of goods, at $2.1 trillion in 2018.

China’s share of global manufacturing has grown significantly. But since 2008 the share of the EU and US has remained stable.

There is considerable variation in China’s production of different goods. But there is little evidence to suggest over dependence on China even for Covid-19 related goods like pharmaceuticals and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Even where China is a dominant manufacturer considerable production takes place for US and EU brands. We should overturn incorrect assumptions and analyse what we can learn from China’s rise for future EU and US policy.

China Manufacturing in Context

It sometimes seems that most of the items consumers buy are from China. That is primarily because certain production is a Chinese speciality. It is less apparent that this accounts for only a small amount of our overall spending.

In this context a useful illustration from the UK shows that 50% of goods imports from China are accounted for by the five categories shown. Many of these goods are of course sold by non-Chinese brands like Apple phones.

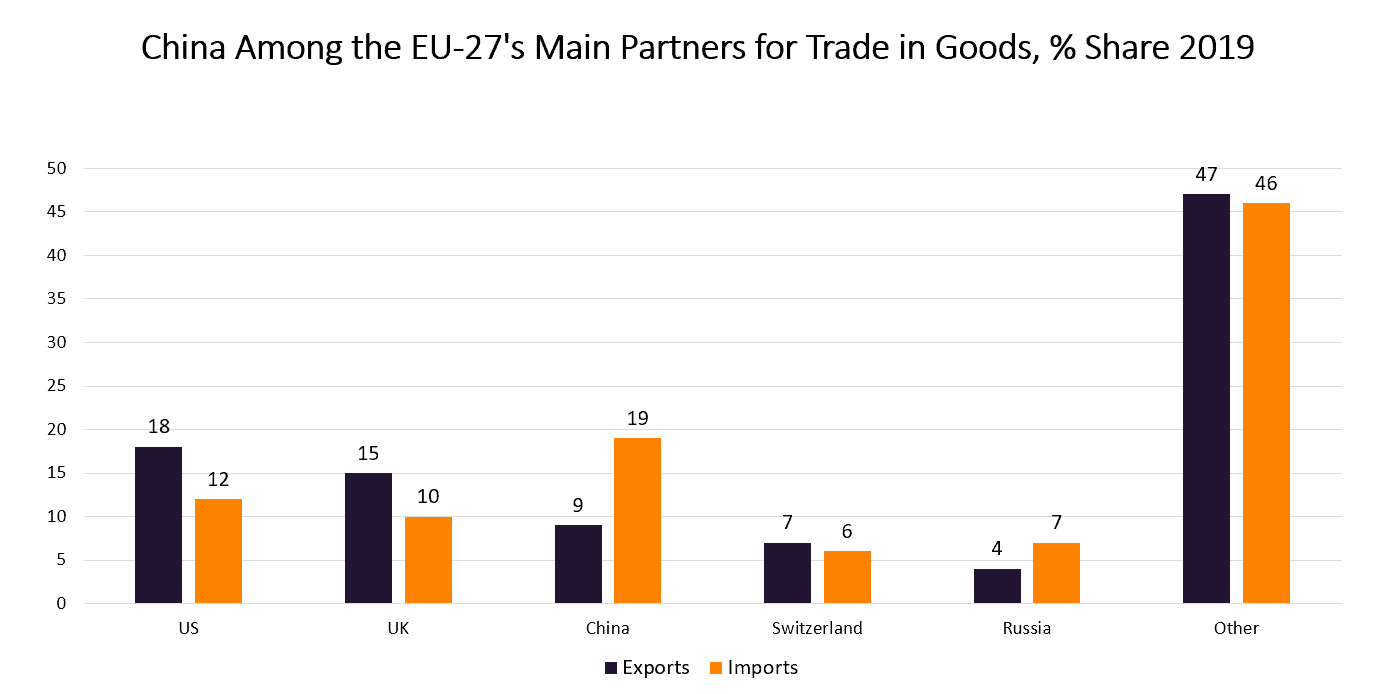

Our perceived dependency on Chinese imports in the EU was analysed by another recent ECIPE study. Out of 424 products in which non-EU countries were found to capture a large share of EU total imports (larger than 80%), China was shown to supply 40%. Yet, Chinese imports only represented 2% of the value of these 424 products, while the US and the UK represented 11% and 15% respectively. In light of these numbers the EU’s so-called ‘dependency’ on Chinese imports is miniscule.

In the EU China is the EU’s largest supplier of imports (19%), but this is hardly a dominant position. We can also see the EU has substantial exports to China, though lower. It is important to keep in mind that due to the nature of global value chains, China is not producing their exports from scratch, and indeed has goods trade deficits with surrounding territories including South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan.

We should also note some manufacturing sectors where China’s domestic production is significant, but exports much less so. This for example includes high speed trains, wind turbines, and electric vehicles. These help account for the trend, unsurprising for such a large country, of trade contributing a diminishing share of GDP, declining from 36% at its peak in 2006, to 19.5% in 2018.

Case Study: Personal Protective Equipment and Pharmaceuticals

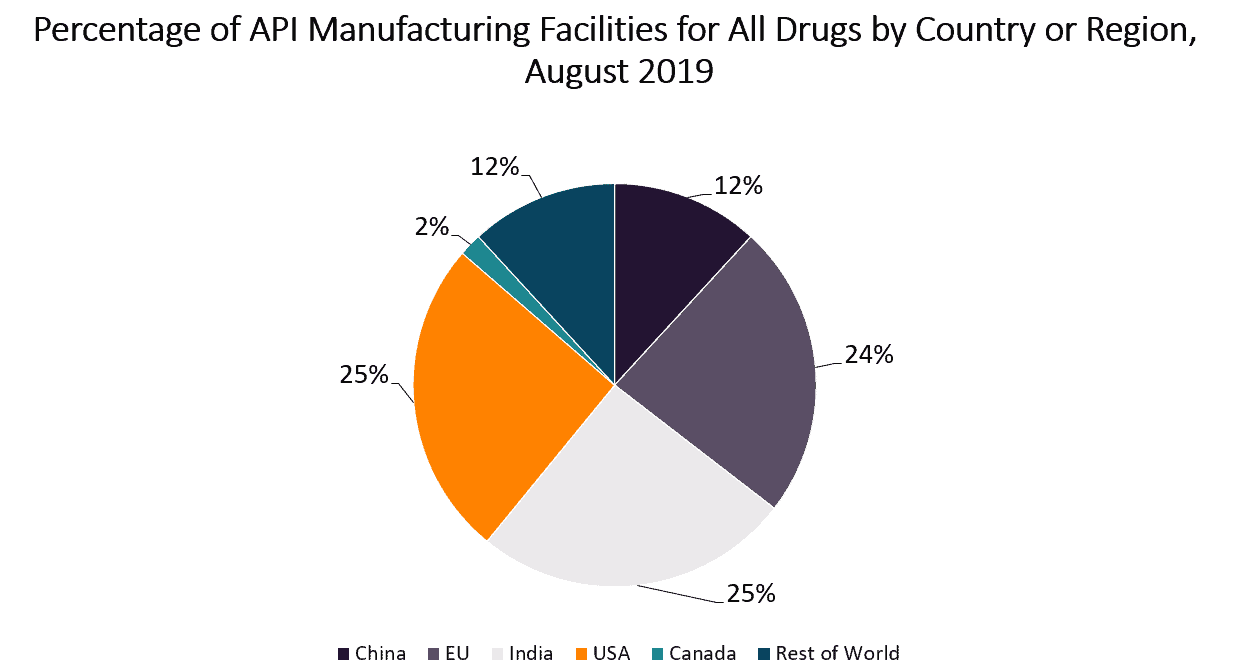

Over the past nine months, there have been many suggestions from policy leaders across the EU and US alike that we are overly dependent on China in combatting Covid-19. However many studies contradict these claims. For example, research on pharmaceutical supply chains presented by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019 illustrated that China does not have any dominance in the production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) when compared to the US, EU or India. Our own research showed that the EU only sourced 2.4% of all pharmaceuticals by value from China in 2019.

With regards to alleged dependencies on Chinese imports of Personal Protective Equipment, another recent study (Evenett 2020) showed the average shares of total imports of PPE that each nation sourced from China from 2015 to 2018. Numerous countries from North America, Europe, and South, East, and South East Asia exported at least $500 million of PPE per annum in this period. Evenett notes in particular that “France and Germany have an unusually large number of foreign suppliers that deliver more than 1% of their import bills for PPE, undercutting claims by these nations’ policymakers that before the pandemic they were too dependent on any one supplier.”

A report released by the US International Trade Commission (ITC) on import sources of a broad range of 203 medical products considered necessary in the combatting of covid-19 revealed that the US has a wide variety of sources. For a majority China was an insignificant supplier, representing between 0 – 10% of all imports in 2019. For only 32 products did China supply more than half of all imports, and China only truly dominated (had >80% import share) 9 import categories, mostly low-cost PPE.

The world is not therefore over-dependent on China in fighting Covid-19 and indeed future pandemics.

Policy Implications

China grew phenomenally to become a global manufacturing power in the 20 years from 1990. As we previously noted in this series, the period also saw technological transformation through the internet, significant growth in global trade through the establishment of value chains, a transition from state provision to regulated economies, and significant trade liberalisation. The transformed global economy resulted from all of these factors.

Arguably China was perfectly placed to take advantage, building at great scale a low cost high reliability high volume manufacturing sector particularly for branded consumer products. This contrasts with China playing only a limited role in major global supply chains such as aviation or automotive, where it lacked deep specialisation, and emerging domestic production is currently mostly targeted at their own market.

The explosive growth of China’s goods exports seems to have peaked, a trend that predates President Trump and US tariffs. China faces demographic challenges of an aging population, pressures of competitors to replicate their manufacturing sector, and technological trends pointing towards global reshoring of some manufacturing production. The response, ‘Made in China 2025’ envisages greater high-tech specialisation, further growth in domestic consumption, and Chinese companies able to compete globally. This is not dissimilar to the path developed countries have taken.

Such a strategy will see China more obviously compete directly with those developed economies, with no guarantee of future success. Many in these countries are concerned about potential unfair competition such as subsidies, drawing on the experience of the last 20 years. As well as proposing stronger disciplines at the WTO they want more freedom for such measures in their own countries. However it is far from clear that unfair competition was the reason for China’s rise, the perceived loss of manufacturing in developed countries, or will affect the high-tech manufacturing competition to come. It may instead be an expensive attempt to imitate parts of the Chinese economy that have not worked so well.

China does not and never did make everything, and its government now wants to change what it does make to be more like the EU and US. The immediate response, to want to be more like China, should be rethought in the light of the facts.