Free Trade Agreements Have Limited Impact (Because Manufactured Goods are a Perfect Market)

Published By: David Henig Anna Guildea

Subjects: New Globalisation WTO and Globalisation

Summary

Free Trade Agreements between two or more countries or parties have been the centrepiece of international trade policy since the formation of the World Trade Organisation 25 years ago. Since 1995, no major round of multilateral trade liberalisation has been concluded, but there has been a sharp rise in the number of bilateral trade agreements. While some of these agreements have real consequences for trade in services and some administrative rules for trade, most of them do not because they focus mainly on tariffs on industrial and agricultural goods. Yet the economic gains from these reductions are now extremely limited. In fact, it is now difficult to improve the global market in goods by cutting tariffs.

Tariffs are low, particularly for non-agricultural goods

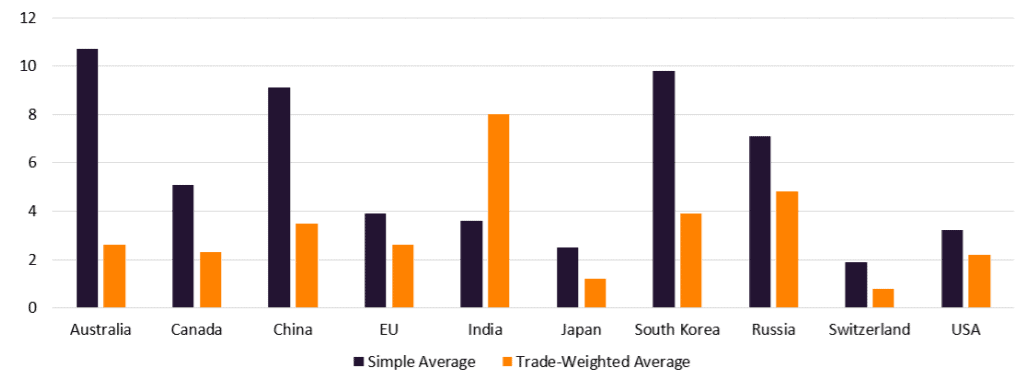

It is estimated that in 1947 the average global tariff for all goods was between 20 and 30%. By 1952, and the first rounds of the GATT, this had reduced to 14%. At this point there were still significant tariffs on swathes of agricultural and industrial goods, for example the average UK tariff on finished manufactured products was 21.4% at the end of the 1950s. By the time of the Uruguay round in the second half of the 1980s the average developed country tariff for all industrial goods was only 6.3%, reducing to 3.8% as a result. The impact can be seen in the chart below, notably showing average applied industrial tariffs of lower than 4% in the EU, US, and Japan.

Tariff Profiles Selected Countries, Non-Agricultural Goods 2018 %

There are different ways to measure the level of tariffs in a country. The simple average tariff includes all tariff lines for a country, but can be distorted by high tariffs on goods that are not-imported. The trade weighted average uses a country’s imports as weights, but can be artificially low as high tariffs impede certain imports.

There are different ways to measure the level of tariffs in a country. The simple average tariff includes all tariff lines for a country, but can be distorted by high tariffs on goods that are not-imported. The trade weighted average uses a country’s imports as weights, but can be artificially low as high tariffs impede certain imports.

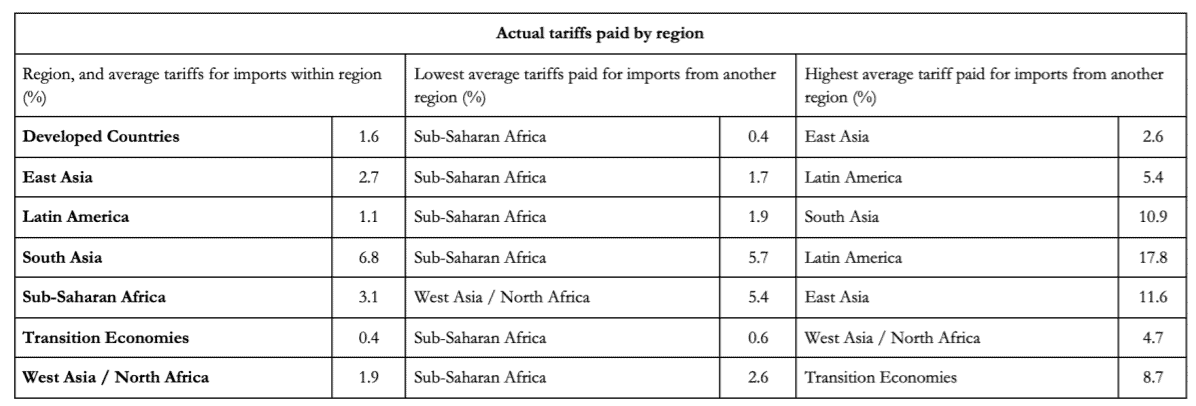

These tariffs, however, are the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) applied in trade with any country as long as there is no bilateral Free Trade Agreement that reduces or eliminates the tariffs. But most countries now have a network of such agreements. UNCTAD’s Tariff Trade Restrictiveness Index takes these into account and shows a much lower actual average tariff paid. It also shows lower rates for intra-regional trade where that network is thicker, and for exports from developing countries given unilateral tariff preferences.

Source: Extracted from Trade Restrictiveness Index (UNCTAD – 2017)

Trade agreements deliver limited results

The primary focus of most Free Trade Agreements remains the reduction of tariffs against the MFN tariff rates, and putting in place rules and regulations to reassure both sides about fair competition. Liberalisation of services and agreements on tackling regulatory barriers are typically second order issues tackled in a less comprehensive and effective way.

Although agricultural tariffs are on average higher than for industrial goods, they comprise only a small share of an economy. Given low industrial tariffs, most bilateral agreements can be expected to have a minimal economic impact.

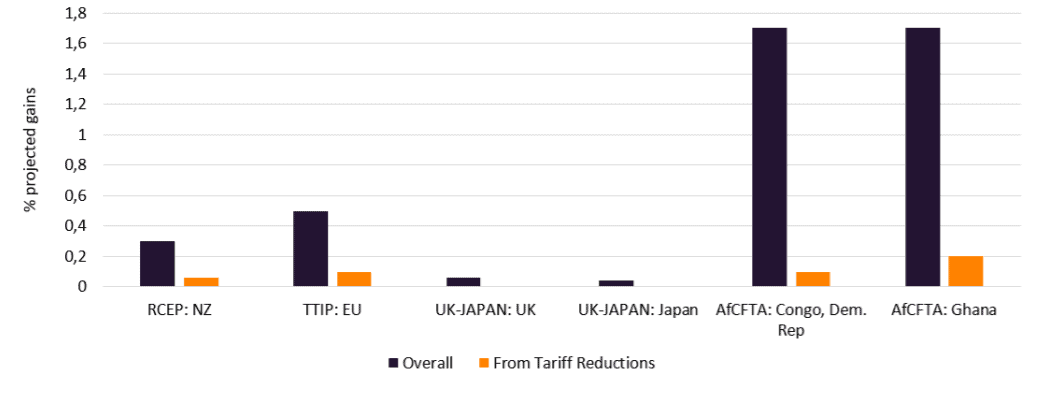

This is indeed what we see when looking at the impact assessments for a number of recent agreements covering both developed and developing countries. The projections are typically positive, but only to a small extent. Where the impact assessments distinguish between the benefits of different content within an agreement, the tariff element is typically the lowest. Thus for example the benefit to New Zealand from joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is estimated at between 0.3 and 0.6% of GDP, of which only a maximum of 0.05% is ascribed to tariff reduction. The gains from the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) are far higher as a result of reducing non-tariff barriers and trade facilitation than from tariff reduction.

%GDP Projected Gains from Selected FTAs

Developed countries still manufacture

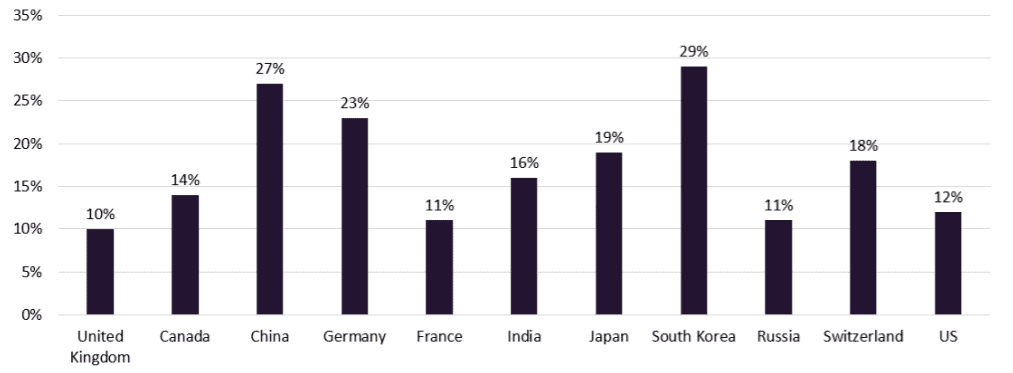

There is a common public view that lowering tariffs particularly with regard to China has contributed to the reduced manufacturing output of developed countries. However, there is no obvious relationship between tariff rates and the percentage of national output covered by manufacturing (source, Brookings Global manufacturing scorecard: How the US compares to 18 other nations, 2018).

% National Output from Manufacturing

We would actually expect manufacturing to continue in developed countries for multiple reasons connected to supply chains and the overall comparative advantages of an economy. For example, perishable goods are always likely to be produced close to the consumer, while companies also value predictability, home country status, and skilled workers among other elements. Low to zero tariffs has not meant a decline in industrial output in developed countries.

Implications

Reducing industrial tariffs in Free Trade Agreements can still have positive effects on individual companies and sectors. But the evidence suggests that this avenue of trade liberalisation is no longer profitable, particularly compared to the effort in crafting such agreements.

We know less about the potentially positive impacts of reducing regulatory and other non-tariff barriers. Trade economists have assumed that competitiveness gains should exist through reducing the cost of regulatory difference. However, outside of the EU regulatory barriers have proved difficult to reduce, economic studies are yet to be fully conclusive, and companies may have become adept at navigating such variations, leaving economic gains modest.

It is worth considering that global industrial goods are now as close to being a perfect market as realistically possible. Consumers benefit from considerable choice, while manufacturers have multiple paths to organise production. Reducing tariffs at the WTO and through various preferential agreements have done the job they were supposed to do in this area. It is now more important to protect these gains than chase diminishing returns from new trade agreements.