Published

Unlocking the Western Balkans: Why Serbia Holds the Geopolitical Key

By: Bernd Christoph Ströhm Philipp Lamprecht

Subjects: European Union Russia & Eurasia

Over the past ten years, Serbia has emerged as the Western Balkans’ top investment destination. Even more impressive is the variety of participants: although EU investors currently hold the bulk of the FDI stock, companies from China, Russia, and more recently Middle East have drawn attention with notable infrastructure, building, and investment projects. The primary justifications made by foreign companies have been an advantageous geographic location, a trained labour-force at a reasonable cost, and a healthy economic dynamic. Because of those benefits, Serbia has evolved into a crucial arena for influence struggles in South-Eastern Europe between actors like China, Russia and the EU. It is not a done deal that the EU is actually winning this tug of war for influence. In fact, it is necessary that the EU adapts its strategies and attitudes to do better in this locale.

Energy, Influence, and Investment: Serbia’s Foreign Policy Between Brussels, Moscow, and Beijing

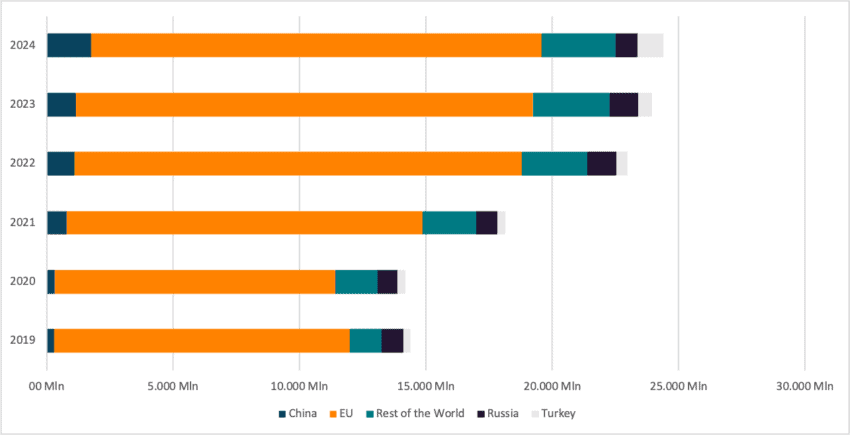

True, it is evident that the EU is Serbia’s main trading partner. In 2023, the EU accounted for some 60% of Serbia’s total trade in goods, with EU Foreign Direct Investment reaching 1.39 billion EUR in 2022. It is also evident that trade between EU countries and Serbia steadily increased over the past five-year period.

Figure 1: Exports of goods, Serbia (2019-2024, in EUR mln) Source: CEFTA

Source: CEFTA

Although the EU continues to be Serbia’s most important political ally and biggest commercial partner, Beijing and Moscow’s influence in Serbia also increased recently. China and Russia have attempted to strengthen their relations with Serbia by providing financial incentives, political backing, and strategic investments.

Russia, for its part, holds robust historical, religious, and political ties with Serbia – rooted in the joint Serbian-Russian Slavic heritage and Orthodox Christianity. Despite Serbia’s ongoing aspirations for EU membership, the country has so far carefully refrained from any attempts to join Western/EU sanctions against Russia, even though Serbia condemned the invasion at the UN General Assembly in March 2022. Yet again, this highlights Serbia’s delicate balancing act that characterises its foreign policy. Russia openly shows its close ties to Serbia, either by granting Serbia the supply of energy under a preferential price regime, or by supporting the country in the “Kosovo” issue, by not recognising Kosovo’s independence since 2008.

Both factors have reinforced Russia-Serbia ties since the end of the Yugoslav breakup wars (the NATO military intervention in Yugoslavia in 1999 further tied Serbia closer to Russia). Since Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine, however, Serbia launched attempts to further diversify its energy supplies, by investing in another gas pipeline to tap into Azeri gas. In December 2023, Serbia completed the Serbia-Bulgaria gas interconnection, linking the country to the Southern Gas Corridor and the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP). Nearly 94% of Serbia’s gas imports in 2023 came from Russia, according to data by the country’s Energy Agency (AERS). This ratio dropped to 92% in the first half of 2024, with almost 8% of Serbia’s total gas imports coming from companies in Hungary, Switzerland, and Azerbaijan.

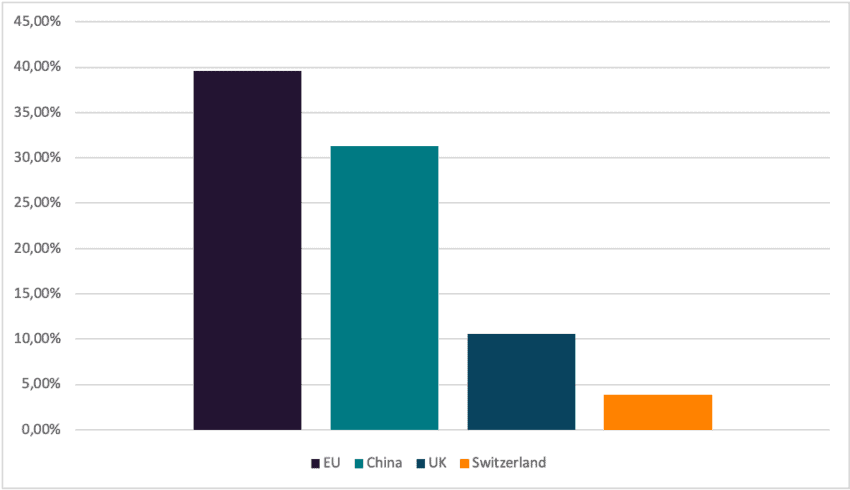

China, on the other hand, is utilising its position as direct investor and bilateral creditor to show its presence in Serbia. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) increased rapidly between 2010 and 2022 in Serbia, reaching a peak of around 1.4 billion EUR in 2022. Over this time frame, China’s total foreign direct investments came to about 4.19 billion EUR. The Serbian Central Bank’s most recent data shows that net FDIs stood at 4.6 billion EUR in 2024. As of the end of 2024, the EU accounted for 39.6% of the overall stock of FDIs in Serbia – China is now following the EU as the second largest investor, with 31.3%.

Figure 2: Net FDI flows, Serbia (2024) Source: Lloyds Bank

Source: Lloyds Bank

China also emerged as one of Serbia’s most significant international trading partners over the last 10 years. To further strengthen this development, the Serbian government signed a free trade agreement with China in October 2023, aimed at increasing trade and collaboration in the automotive, technology, agriculture, and commodities sectors. This free trade agreement also has symbolic meaning since it was the first ever free trade agreement between a country in Central and Eastern Europe and the People’s Republic of China.

Mining Diplomacy? Serbia’s Strategic Role in the EU-China Resource Race

The contest for influence also expands into other areas. Serbia’s substantial endowment of natural resources (especially lithium, copper, and gold) also attracted the interest from non-EU actors, most notably China. The importance of Serbia’s natural resources was also evident in FDI flows, with mining and quarrying being the sector which had received most FDIs in 2024. Over the past decade, particularly China markedly expanded its footprint in Serbia, not only through substantial infrastructure investments but also as a major stakeholder in the mining sector. In 2018, the Serbian government declared the Chinese Zijin Mining Group as a strategic partner for the Bor mining and metallurgical complex (RTB Bor). With this announcement, Serbia also facilitated the Zijin Mining company’s takeover of the RTB Bor copper complex, which also included a commitment of an investment of over USD1 billion, including a pledge to improve environmental standards. The Zijin Mining Group received a 63% majority stake of the RTB Bor complex and pledging to safeguard 5,000 mining jobs in Bor.

What about the EU? To lessen its reliance on Chinese imports, the EU is looking for supplies of lithium for use in electric vehicle batteries and recognised Serbia’s advantageous position in the mining sector with the country’s rich lithium reserves. This is why it organised a raw material summit in Serbia in July 2024, aimed at facilitating mining operations in the Jadar Valley. The so called “Jadar” project should position Serbia as a leading supplier of lithium—a resource which is considered as critical for electric vehicle batteries. The mining operation should be led by the Rio Tinto multinational mining corporation.

It is notable that particularly the Jadar project had positioned Serbia into the centre of international competition for green energy materials, with both the EU and China vying for access. The European Commission finally recognized the extremely contentious Serbian Jadar lithium mining project as a “strategic project” in June 2025, alongside 13 other new strategic projects pertaining to vital raw resources in third non-EU countries. According to the EU, the launch of those strategic projects would require a total capital expenditure of EUR 5.5 billion. Interestingly, despite Rio Tinto’s announcement that it will also construct a processing facility, the European Commission only approved the extraction portion of the project.

It needs to be stressed that the general rush to exploit Serbia’s mineral wealth had also generated considerable environmental and social resistance in Serbia. Local opposition to mining projects, driven by concerns about pollution, land degradation, and transparency had already caused a series of large-scale protest rallies across the country in 2021–2022 and renewed protests in 2024. Thus, Serbia faces the ongoing challenge of balancing economic development with environmental sustainability.

The 2025 Student-Led Protests and Serbia’s Democratic Crossroads

Since early 2025, the Serbian government is also confronted with nationwide student-led protest rallies, caused by the collapse of a canopy in the Novi Sad railway station in November 2024, leaving 16 people dead. The Novi Sad railway station incident initially sparked widespread outrage over corruption and government negligence. With record numbers of people assembling in the Belgrade city centre calling for authorities to take responsibility for the Novi Sad tragedy, Serbia also saw what some are estimating to be the biggest protest in its history in March 2025. The protests, led by students and civil society groups, have evolved since then into a broader protest movement, demanding transparency, democratic reforms and snap parliamentary elections.

Those 2025 anti-government protests have potential geopolitical implications. They are a sign of increasing public discontent with the current rule in the country and could impact Serbia’s foreign policy direction. These tensions reflect the larger tussle over influence within Serbia and might undermine President Vucic’s political ambitions.

The Bigger Picture: How the EU Needs to Adapt Its Strategy in Serbia and the Region

In the last 15 years Serbia has positioned itself as a geopolitically and economically vital country in the Western Balkans, owing to its strategic location and abundant natural resources. The influx of FDIs, particularly from the EU and China, further underscores Serbia position as a strategic actor in the region, also when it comes to EU expansion. Serbia’s openness to international partners and trade have spurred economic growth, especially in the energy, infrastructure, and mining sectors. Still, Serbia remained well integrated in commerce with the EU.

Considering these complex dynamics, what should the EU do in order to retain its influence and prevent Serbia and other countries in the region from slipping away into the sphere of influence of other powers like Russia and China? Applying a more geo-economic view on the South-Eastern Neighbourhood and elevating strategic issues of geoeconomics in the Southeast region to a clear priority among EU policymakers in Brussels is needed more than ever. It is necessary to bring the economic and the political reality of Southeast Europe more prominently into the EU discussion and to be more cognisant about geopolitical developments in the region. The EU has largely been missing in action. Here, a focus needs to be set on China, as bilateral creditor, and on Russia, as energy provider in the Western Balkans region.

As a geopolitical actor, the EU should also do more than just boost its economic presence in Serbia. It is simultaneously necessary to show a deeper appreciation to surging concerns in Serbia’s civil society. An evident illustration of the rift between EU policymaking and Serbian civil society concerns is the still persistent widespread opposition to the Jadar lithium mining project. This opposition caused massive environmental-driven protests in Serbia, initially persuading authorities to briefly pause plans for lithium mining in 2022. Additional doubts about the EU’s role in steadfastly backing the controversial operation — despite local opposition — further deepened scepticism towards Brussels in Serbia. If the EU wants to truly keep its credibility and remain influential in Serbia in the long run, it needs to boost its visibility by increasing its involvement with the country’s civil society organisations that is opposing the lithium mining deal. Approaching Serbia narrowly from an economic point of view would be a huge blunder by the EU.

Given the clear priority of countries like Serbia, EU policymakers should unite their own priorities and the political and economic realities on the ground in Serbia and other countries in the Western Balkans. The EU involvement as investor should also be reviewed to assess what can be optimised. Here, investment plans such as the “Global Gateway Initiative” as well as the “Critical Raw Materials Act”, and its impact on Southeast Europe, should be examined closer.

The involvement of non-EU actors in the Western Balkans could further inhibit the EU integration process of the region. The recent EU lithium mining agreement, brokered between the EU and Serbia in July 2024, can be used as an overarching example of the EU being in a geostrategic important position in the region, particularly vis-à-vis China.

A more geopolitical understanding of these issues is timely and important due to a number of factors. First, there is a clear strategic importance of Southeast Europe for the stability and security of the broader European region. Second, there are ample economic opportunities for EU businesses (particularly in the energy sector) in a more stable and strategically aligned Southeast Europe. Finally, this region is a clear example of missing policy influence. It is key for the EU to contribute more strongly to shaping a more secure and prosperous European neighbourhood.

But has the EU actually been a good neighbour? ECIPE scholars and colleagues at Bertelsmann Stiftung have focused on assessing the extraterritorial costs of various EU internal market regulations on its neighbouring countries engaged in trade with the EU, including the Western Balkans. A central mission has been to propose methods to mitigate the regulatory burden on these neighbouring regions. Our analysis is crucial as the EU seeks to maintain its regional influence amidst growing competition, notably from China and Russia. There are numerous examples of EU internal market regulations that result in negative effects for close neighbours and risk pushing them away.

We propose mitigating measures, for example alleviating the serious and negative effects that the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) can have on EU neighbours. In our work, we also found that EU digital regulations have adverse extraterritorial effects on them. We propose a rethink of the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) to enable agricultural export diversity in the EU neighbourhood. And we discuss how the EU can work to improve trade finance access for neighbouring countries. A fifth policy paper examines the extraterritorial effects of the EU’s indirect land use change (ILUC) provisions introduced in various regulations.

The bottom line is this: EU policymakers should invest in better relations with neighbouring countries, including the Western Balkans, and take measures to prevent EU regulations from pushing these neighbours away from the EU.

This approach means improving the objectives and results of regulation, including the process of how the EU does things. Design matters. It is remarkable how little the EU has consulted with neighbours before crafting and finalising new regulations. The EU should reconsider how it engages with its neighbours during the design phase of regulations and policy measures. For example, coordinating more with allies and like-minded countries on including mechanisms for third-country compliance would lead to less frictions. For regulation to be effective and avoid stoking negative reactions by friends, the design should be smart and agile, and take into account mechanisms that allow other countries to adapt more easily. This also includes internal processes within the EU such as EU trade policy building knowledge and generating analysis of potential impacts. EU assessments in this regard should by design focus more on the impacts on the EU’s neighbouring countries, including Serbia.

Finally, integrating the EU as a genuinely engaged and reliable player in the Western Balkan region means supporting democratic institutions, engaging in civic participation, and advancing sustainable development. The EU should be clear about its commitment though – that its dedication to the region is about more than just economic cooperation and mining concessions.

Great overview. The „Bigger Picture“ part is particularly helpful, it could prove worthwhile to elaborate even more in detail and concretely on the way the EU should take respectfully account of and „bring in“ Serbia – and indeed the other long-time accession countries.

EU needs to revise their stand on so called Kosovo* if they want to have Serbia truly on their side. Also Republika Srpska in BiH needs to be given right of self determination if they want. Kosovo* needs to be solved in win-win manner (hint: North to Serbia and protection of Serbian cultural heritage). Until then, China and Russia will have leverage.