Published

Six Months into the Second von der Leyen Commission – Where are the Policies for Long-Run Economic Growth?

By: Fredrik Erixon

Subjects: European Union

There are different ways to think about the economy. Economic reality will routinely present any policymaker with challenges that require actions in the short term: crises that motivate cyclical responses, for instance. But it is notable how the muscle memory of many European economic policymakers has been re-programmed over the last two decades: policies for long-run economic growth no longer come naturally to them. Even when presented with a long-term problem, most leaders now go for a short-term response.

Yes, the rhetoric is of course there: Ursula von der Leyen and every other European leader want all the other stuff as well: better productivity, more innovation, more start-ups and scale-ups, more venture capital. Yet the mandatory declarations of support, or routine calls for “smarter” or “green” or “digital” growth, don’t seem to guide their actions. The reality is that the only economic policy that is operational these days is the one that primes the economy for some cyclical improvements and better outcomes in the short term.

How did such policies perform? Enter Mario Draghi! Famously, the Draghi report conveyed a hard message about European economic stagnation and delivered analyses that many of us in the world of economic policy research have been saying for a long time: Whatever it is you are doing, Europe, it isn’t working!

As Draghi noted, on most metrics that help to shape long-term prosperity generation, Europe is falling behind – and has done so for a long time. Draghi’s report on The Future of European Competitiveness has since its launch last autumn reach divine status: it’s the Bible of von der Leyen’s European Commission. Anyone who aspires to get a policymaker to listen to their ideas, need to start with a homage to the former Italian Premier and central banker.

However, it is soon six months since the new Commission took office, and so far it does not have much to show for itself. It seems to honour Draghi’s report “more in the breach than the observance”, to quote William Shakespeare. What has been achieved so far? I want to be emphatic and generous but, to use a round number, the outcome has been close to zero. There is talk about talks, strategies about strategies, and – obviously – plans about plans: it’s success measured in bureaucratic activity rather than in real achievement.

Remarkably, even the plans are falling short on ambition. True, the Commission talks about “simplification” in regulation and has produced an Omnibus bill to that effect: alas, it won’t move the needle much in regulatory burdens and costs, let alone value-adding economic activity. There are plans for investments, trade, industrial policy, the single market – and, helpfully, there are some delays of the implementation of new regulations and new burdens. But as anyone with a deeper understanding of long-run growth will observe: much more will be needed, even in the scenario where these plans are implemented.

Then there is the White Swan – or, perhaps, the “Orange Swan”: a shock to the European system that was foreseeable, now represented by Donald Trump. His assaults on trade and the economy (and everything else) have added a new complexion to Europe’s economic condition. Some in Europe talk about Trump and MAGA craziness being an opportunity for Europe: a time for it to shine and claim back economic talents and fortunes lost in global competition. Good luck! Others see, more realistically, that there is an extraordinary risk of collisions and crises that will have huge impact on Europe’s economy and welfare, and that the US no longer will be an ally in the way it used to be also in the economy. Trump’s actions mean that Europe must act much faster and with greater determination to become a source of innovation and economic growth. It needs to recover the economic model that powered European economic policy for several decades: incentivising long-run economic growth. Yes, growth powered by faster productivity growth and more consequential entrepreneurial activity.

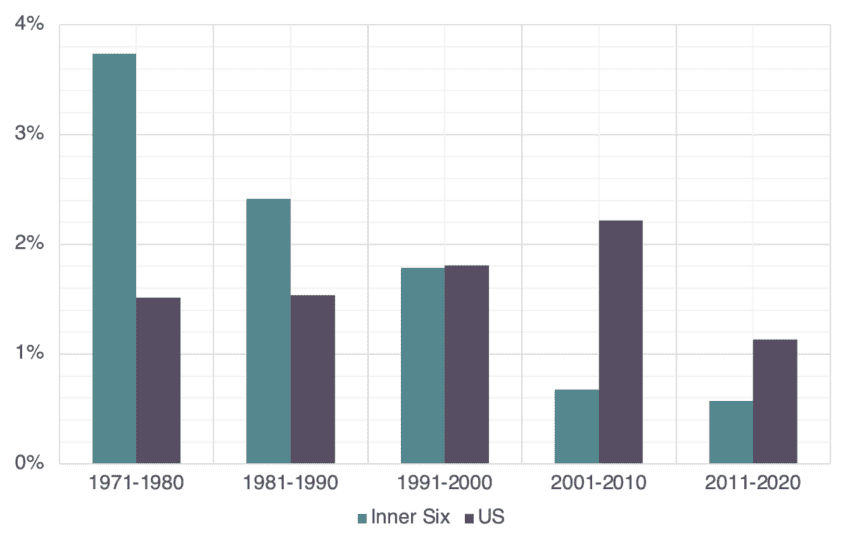

Importantly, Europe’s problem with long-run economic growth is concentrated to the larger economies. The chart below, taken from a paper by a colleague and me last summer, compares productivity developments between the “Inner Six” countries in the Euro Area (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) and the US. For several decades, European economies had faster growth than the US: since the 2000s, the US has grown its productivity much faster than the “Inner Six” countries. The difference is remarkable: between 2001 and 2020, US productivity was more than twice as big as in the six EU countries.

Figure: Average annual growth of Inner Six and US, GDP per hour worked by decade, 1971–2020 (percentage, constant prices) And what has been the development in the past five years? The gap remains substantial – and it is increasing. Between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2024, EU labour productivity per hour worked increased by 0.9 percent in the Euro Area and 6.7 percent in the US. Developments under these years also make it abundantly clear where, more exactly, Europe fails. Consider the figure below, decomposing productivity growth between 2019 and 2024. There are very significant gaps between the Euro Area and the US in the two sectors that are critically important for long-run growth: industry and market services. Hourly productivity gains in the US in this period was five times higher than in the Euro Area, and it was three times higher than in market services. Helpfully, public services performed better in the Euro Area than in the US, and such development should not be dismissed: public services are a big sector. However, long-run growth will not from these services.

And what has been the development in the past five years? The gap remains substantial – and it is increasing. Between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2024, EU labour productivity per hour worked increased by 0.9 percent in the Euro Area and 6.7 percent in the US. Developments under these years also make it abundantly clear where, more exactly, Europe fails. Consider the figure below, decomposing productivity growth between 2019 and 2024. There are very significant gaps between the Euro Area and the US in the two sectors that are critically important for long-run growth: industry and market services. Hourly productivity gains in the US in this period was five times higher than in the Euro Area, and it was three times higher than in market services. Helpfully, public services performed better in the Euro Area than in the US, and such development should not be dismissed: public services are a big sector. However, long-run growth will not from these services.

Figure: Hourly Labour Productivity Growth by Sector Here’s my point: Long-run growth is missing in Ursula’s actions. Compounding the problem is that long-run growth is also missing in actions by Emmanuel, Pedro, Giorgia, and other European leaders. They all talk the talk but, except for Greece (some countries could also get an honourable mention), no one is really doing anything with significant impact. What they all should do is to address three fundamental markets that are dysfunctional because of regulation: capital markets, energy markets, and technology markets. These sectors are of great importance for the entire economy and Europe has chosen a path of regulation that depress economic activity. To this list we can add other structural reforms that are needed: better market access to the growing part of the world economy, reforming pay-as-you-go pension systems, reducing business and ownership taxation, cutting business cash subsidies, and incentivising more business R&D spending. The list could be made much longer.

Here’s my point: Long-run growth is missing in Ursula’s actions. Compounding the problem is that long-run growth is also missing in actions by Emmanuel, Pedro, Giorgia, and other European leaders. They all talk the talk but, except for Greece (some countries could also get an honourable mention), no one is really doing anything with significant impact. What they all should do is to address three fundamental markets that are dysfunctional because of regulation: capital markets, energy markets, and technology markets. These sectors are of great importance for the entire economy and Europe has chosen a path of regulation that depress economic activity. To this list we can add other structural reforms that are needed: better market access to the growing part of the world economy, reforming pay-as-you-go pension systems, reducing business and ownership taxation, cutting business cash subsidies, and incentivising more business R&D spending. The list could be made much longer.

There are, obviously, short term economic concerns that need responses. But as Team Ursula now ponders new and fresh economic initiatives, it should start thinking about structural reforms that can help revive innovation, dynamism, investment, productivity, and growth. Obviously, substantial reforms are needed to deepen the single market in services – and such reforms will be about taking away both EU and national regulation. The EU desperately needs a new trade policy based on constructive trade negotiations with other parts of the world – especially as trade with the US will be exposed to new frictions. Importantly, the EU needs to free up regulations especially in the deep technology and digital sectors, and start making the regulatory climate for new technology experimentation and innovation hospitable again. For instance, take away regulations that prevent scientific experimentation with CRISPR and other biotech development: last week some exciting news came out of UPenn while Brussels was discussing a compromise opening the door a bit more for gene-editing technologies. The AI Act and has not taken effect yet and perhaps the single most consequential action the EU could take now is to make sure it never will. It needs to go back to the drawing table and come up with something that primes Europe for AI investment, use, experimentation, and innovation.

There is an optimistic moral. Europe could again prosper and place itself at the frontier of innovation-led growth. Our problem is not one of culture and risk aversion. No country is ever doomed or permanently demoted to low economic expectations. When countries improve policy, people respond with supportive action. When policymakers make the economic environment more welcoming, people will come. When new economic opportunities are presented, entrepreneurs and innovators will use them.