Published

Populist Rhetoric in the EU Debate Over Taxing Corporations

By: Matthias Bauer João Carvalho

Subjects: Digital Economy EU Single Market European Union

On October 14, ECIPE hosted a seminar on Europe’s tax competitiveness. The aim was to outline new evidence for tax policymakers, with a focus on the characteristics of national tax systems and flaws in the design of corporate tax regimes.

The event started with a presentation by Daniel Bunn (US Tax Foundation) on the Tax Foundation’s International Tax Competitiveness Index 2019 (ITCI). Mr Bunn was followed by presentations by James Watson (BusinessEurope), Jacob Lundberg (TIMBRO) and Matthias Bauer (ECIPE), who highlighted the negative economic and distributional impacts of corporate taxes that should be accounted by EU policymakers.

Daniel Bunn presented elements of the ITCI that summarise the relative “competitiveness” of tax systems across the OECD, which includes EU Member states. The index assesses the neutrality (minimal distortions in behaviour) and competitiveness (keeping marginal tax rates low) of a country’s overall tax system. Mr Bunn highlighted that taxes always change individual behaviours. He added that taxes can, however, be designed in ways that minimize distortions in people’s behaviours.

Daniel Bunn (US Tax Foundation): “In the background, we are thinking about how will a tax system impact economic growth”, because “taxes influence the cost of capital and labour, which has effects on the ability to create something in the economy.”

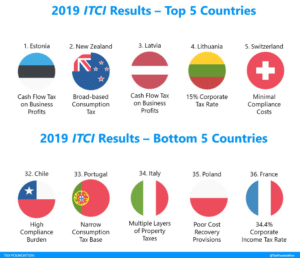

In the ITCI, countries are ranked according to the design of their tax policies.

Referring to the ITCI, Daniel Bunn revealed that:

- There is a lot of diversity in tax systems across the EU. Estonia, ranking first for six years in a row, only applies corporate taxes when dividends are distributed to shareholders. It does not tax corporate investment, which in turn does not unnecessarily impair economic development. The government of Latvia recently copied the Estonian model. Latvia is now ranking third in the index.

- France was found to be the least tax competitive for the 6th year in a row. The French government imposed the highest corporate income tax rate in the OECD. The French tax code imposes multiple, often opaque, layers of property taxation and numerous special provisions and exemptions in the corporate taxation that create distortions.

- The US, which recently saw a far-reaching corporate tax reform, rose in the ITCI ranking from 28th to 21st. The US corporate tax reform now allows for the full expensing of short-lived assets. The US also moved away from a worldwide to a territorial tax system and lowered the combined corporate rate from 38.9% to 25.9%.

Daniel Bunn also argued that, compared to the US, there has been little appetite for lowering corporate taxes in the EU. By contrast, some EU Member States proposed to impose special taxes on digital services (digital services tax, DST). Instead of improving VAT systems to address the sales of digital services, proposals across EU member states to tax digital services have been “non-traditional”, targeting gross revenues rather than net profits.

Matthias Bauer discussed whether unfairness should be maintained in corporate taxation. He highlighted that EU and OECD policymakers disregard the incidence of corporate taxes, particularly the burden that is borne by workers and consumers, which negatively impacts tax progressivity. Dr Bauer referred to a 2018 study by Clemens Fuest, Andreas Peichl and Sebastian Siegloch, which finds that the corporate tax burden falls disproportionately on low-skilled workers, female workers and young workers.

James Watson presented a recent study conducted by the European Economic and Social Committee on corporate taxes and their impact on jobs and investment in the EU. He argues that tax policies are often misguided public perceptions. “There is a perception of rising income inequality, and that corporations are not feeling the pain of the crisis equally,” says Mr Watson, “however, corporate tax contributions have been on the rise”. According to Mr Watson, EU policymakers still fail to account, in their analysis, for the importance of tax incidence. Mr Watson also highlighted that the corporate tax incidence (the economic burden) falls on individuals, on workers and consumers. For Mr Watson, the discussions surrounding corporate taxation need to be better informed, with more complete impact assessments. Mr Bauer added that there is a lot of evidence of tax obfuscation, in which politicians and government officials frame the debate about corporate taxation, focussing on fairness, not acknowledging that these taxes will eventually hit individuals’ wallets.

Jacob Lundberg argued that corporate income taxes should be abolished in the long run. From a theoretical perspective, “[t]he corporate income tax causes many different distortions”. For example: as firms can usually deduct debt interest from the corporate income tax and dividends are usually taxed twice (at the firm and shareholder level), there is an incentive for creating debt by borrowing more (instead of equity investment). This increases financial instability, tax avoidance (through internal loans) and makes markets more favourable to industries like real estate (who can provide collateral) than tech corporations. Literature has further shown that when a country introduces a corporate income tax, the required rate of return on investments rises, resulting in fewer projects that receive investment. Mr Lundberg also argued that there is a lot of empirical evidence that corporate income taxes shrink capital stock, workers’ wages and productivity.

The panel agreed that there is a lot of misinformation and populist rhetoric in the EU debate over taxing corporations, while the negative consequences –– deliberately or not –– are being ignored by politicians and tax officials. Corporate tax policymaking will always have an impact on the competitiveness of the European economy. Corporate taxes will always impact on citizens’ disposable incomes, through lower wages for workers and higher prices for goods and services for consumers. Advocates of corporate taxes (e.g. in the OECE, in the European Commission’s tax department DG TAXUD, representatives of corporate tax advisory companies) fail to make the case for why corporate taxes should exist in the first place. They also fail to offer alternative rules for taxation – rules that are simpler, more transparent and considered fairer among large parts of the population.

Given that in the EU corporate taxes account for fairly low shares of government revenues in total tax revenues (e.g. between only 5% and 6% for Germany and France), EU policymakers should consider to abolish taxes on corporate income, and focus more on direct taxes on capital income, labour income and consumption. In the meanwhile, the policymakers’ goal should be to push for a more informed discussion and, perhaps, take inspiration from countries like Estonia (and Latvia).