Published

Navigating Merger Reforms in Australia: Recommendations to Australia’s Competition Taskforce

By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: Regions South Asia & Oceania

Focusing on proposed reforms of merger enforcement in Australia, this article discusses key issues highlighted by the Competition Taskforce and major changes recently proposed by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC). The article is organised into three main sections: the effects of mergers on competition and productivity growth, the consequences for merger enforcement in Australia, and the potential for minor adjustments based on ACCC recommendations.

Executive Summary

ECIPE contests the necessity of a fundamental revision of Australia’s merger enforcement framework.

We challenge the interpretation of data indicating increased mark-ups and industry concentration. Several recommendations put forth by the ACCC should be met with caution as they would increase legal and economic uncertainties and undermine Australia’s attractiveness to domestic and foreign investors.

The slowdown in Australia’s productivity growth is attributable to poor technology adoption, inadequate corporate taxation, and challenges in the education system, rather than shortcomings in the current merger control system. It is imperative for Australia’s government to improve technology adoption, taxation policies, and education to foster productivity growth. Substantial changes to the existing merger regime, as proposed by the ACCC, would further reduce Australia’s investment attractiveness.

To minimise negative consequences of mergers and acquisitions, we recommend that when conducting pre-emptive merger investigations in technology- and knowledge-intensive sectors, it is essential to consider well-documented efficiency and innovation gains and to avoid negatively impacting Australia’s productivity growth by making the Australian unattractive to foreign investment.

A. The importance of contextualising Australia’s productivity concerns

There is no need to reform merger policy in Australia. The government’s rationale is misleading and based on wrong interpretation of data. Changing merger policy will not solve Australia’s challenges as claimed by the ACCC.

The productivity slowdown cannot be ascribed to the present merger control framework.

As outlined by the Competition Taskforce[1], Australia indeed observed a slow-down of productivity growth. However, data suggestive of a decline of economic dynamism, such as industry concentration ratios and mark-ups, are misleading with respect to mergers. The data referred to in the consultation paper are not indicative of specific industry developments and must not be misinterpreted in the context of merger enforcement. Australia’s productivity weaknesses can be attributed to poor horizontal and sector-specific regulations.

Mark-ups and productivity should not be interpreted in a misleading way.

There is no hard evidence for increased mark-ups in the Australian economy, and even if such evidence existed, increasing mark-ups do not necessarily reflect a reduction in competition.

The Australian Competition Taskforce should interpret industry mark-ups cautiously, acknowledging their limitations, using complementary indicators for nuanced insights, and recognising that rising mark-ups often indicate efficiency gains and innovation rather than anti-competitive practices.

Further, the data points referred to in the consultation paper appear to be selective. The analysis quoted by the Competition Taskforce indicates an average increase of some 6 percent in firm mark-ups between the fiscal years 2003−04 and 2016−17. Since only one aggregate number is presented for the entire “non-financial economy”, the analysis does not provide any meaningful information on the real, inflation-adjusted price developments within specific industries in Australia. Generally, industry mark-ups are flawed indicators of competitive pressure due to challenges in precise measurement, variability across industries, the dynamic nature of markets, and quality-adjustment difficulties. In global and digital markets, traditional industry-based mark-ups also do not fully capture the complexities of competition and the contestability of markets. Accordingly, caution is warranted when interpreting industry mark-ups, emphasizing the need for various complementary indicators to ensure a nuanced understanding of competitive pressures in specific markets.[2] For example, many experts argue that rising mark-ups can indicate heightened efficiency and advanced technology stemming from innovative practices.[3] Multiple studies examining the influence of product market regulations on mark-ups in EU countries reveal that less restrictive regulations, particularly those easing entry and reducing trade barriers, are linked to lower mark-ups. The impacts vary among sectors and specific regulatory measures, especially in regulated services industries.[4]

OECD data clearly demonstrate that larger companies show on average higher levels of labour productivity than smaller companies, emphasizing a robust correlation between company size and productivity across countries and industries.[5] Much of that success can be attributed to investments intangibles, i.e., innovation, R&D, and patents, which are key drivers of prosperity and economic development and renewal.[6]

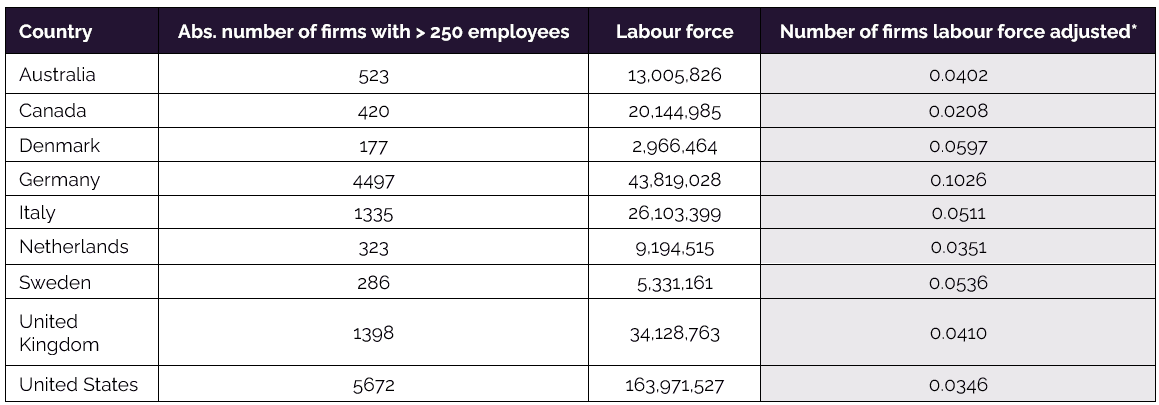

OECD data also show that Australia has a moderate concentration of large firms relative to its labour force compared to the other (large and small, industry- and resource-intensive) OECD countries. There seem to be several structural barriers to business growth and mergers in the Australian economy (see below). It is thus inaccurate to insinuate that an accommodating approach to merger control in Australia has consistently led to an undue concentration of large companies (with associated rises in mark-ups).[7]

Table 1: Number of firms with more than 250 employees, selected large and small OECD countries

Source: OECD. Enterprises by business size. 2017 data (latest year for which data is available for Australia). Available at: https://data.oecd.org/entrepreneur/enterprises-by-business-size.htm. *= Number of firms divided by labour force multiplied by 1,000.

Source: OECD. Enterprises by business size. 2017 data (latest year for which data is available for Australia). Available at: https://data.oecd.org/entrepreneur/enterprises-by-business-size.htm. *= Number of firms divided by labour force multiplied by 1,000.

The Competition Task Force refers to evidence indicating “that declining firm entry rates have contributed to a reduced rate of convergence to the productivity frontier within industries, and that the rate of convergence is slower within industries that have experienced the largest increases in markups.” It is crucial to acknowledge that hostility towards mergers and acquisitions discourages new entrants. Investors and founders can be deterred by the concern that the prospect of selling the company as a potential exit strategy could become unattainable.

Australia’s sluggish productivity growth is caused by weak structural business conditions.

An overwhelming body of economic research demonstrates that larger firms experience higher levels of productivity and productivity growth due to the interplay of various factors. This can come from economies of scale, which enable larger firms to produce goods and services more efficiently at lower average costs, contribute to enhanced productivity. Larger firms also have greater access to resources, technology, and skilled labour, fostering innovation and efficiency improvements that drive overall productivity growth.[8] Large domestic firms can also generate total factor productivity spill overs similar to large multinational corporations.[9] Recent research also indicates that larger companies demonstrate greater resilience in the face of a tightening of financial conditions, reflected by a firm size premium in total factor productivity (TFP) growth, with larger firms experiencing less adverse effects on TFP compared to smaller firms.[10]

The Competition Taskforce notes a recent global slowdown in Australia’s productivity growth. This slowdown is characterised by a widening gap between firms at the technological frontier and other “laggards” within industries, indicating slower adoption of cutting-edge technologies and business processes by the latter. Research suggests that Australian firms are catching up to the global frontier more slowly than before, especially in industries with declining competitive pressures.[11] The study emphasizes that Australia should improve incentives for Australian firms to adopt new technologies, innovate, and improve. It is explicitly highlighted that the Australian government should embrace “[p]olicies that facilitate more widespread adoption of emerging digital technologies can also play a role in improving productivity performance.”

The primary responsibility for enhancing productivity lies with national policies, including fiscal and structural measures, high-quality education, and the rule of law. For Australia, various data suggest that the country is performing below OECD average. Australia is a high tax country, as demonstrated by high statutory and effective corporate tax rates.[12] In fact, all companies are subject to a federal tax rate of 30% on their taxable income, except for “small or medium business” companies, which are subject to a reduced tax rate of 25%.[13] Importantly, an analysis of mark-ups – and derivation of recommendations for competition policy – cannot do without an analysis of the effective tax burden.

Moreover, Australia’s important services sector is highly regulated, with many trade barriers preventing external competitive pressure from arising. It is noteworthy that the most recent 2022 services trade restrictiveness (STRI) indicator is below the OECD average compared to all countries in the STRI sample.[14] Australia also is a highly restrictive jurisdiction for foreign investment compared to its peers, especially OECD countries, with adverse impacts on “investment uncertainty” and private sector investments.[15] Concerning the adoption of (digital) technology, many Australian businesses face barriers to adopting new technology and data usage, with common issues including inadequate internet infrastructure, skill shortages, limited awareness, and uncertainties about benefits, costs, and legacy systems. Agriculture businesses, particularly in regional and remote areas, highlight challenges related to unsuitable internet speed and geographic location, while medium and large enterprises often cite high costs associated with transitioning from legacy systems as a significant impediment.[16]

Against this background the Australian Productivity Commission has carried out various analyses and made several important recommendations.

None of these recommendations see the need for merger control reform. Importantly, concerning impediments to entry or exit (which is a major rationale underlying the merger enforcement reform), the Productivity Commission in 2017 urged for a reform agenda that focuses on tight product standards, pharmacy regulations, restrictions on retail trading hours, taxi regulations, and issues related to professional licensing and air services agreements.[17] The most recent analysis by the Productivity Commission calls for substantial changes to Australia’s education system, advocating, for example, for a return to a demand-driven university system. The report generally emphasizes the importance of human capital over physical capital in enhancing productivity in Australia’s overall economy.[18] Regarding data and digital policies, the Productivity Commission recommends better conditions for the sharing health and government-funded service data and utilizing migration policy to address workforce gaps and acquire digital and data skills that may be challenging to develop locally.[19]

B. Implications for merger enforcement in Australia

Australia’s current merger control regime is effective and proportionate. Over 1,500 mergers have been reviewed by the ACCC over last two decades. Of those, only 7 have been brought to the Federal Court, and of those 7, two were withdrawn before trial, and one was resolved by undertakings given to the ACCC. It is clear that, by and large, potential merger parties take Australia’s merger control regime seriously and only attempt M&A activity that will not fall foul of the prohibition on anticompetitive mergers.

Mergers, overall, contribute to investment and productivity growth in the economy by fostering economies of scale, enhancing resource utilization, and providing access to new markets. The combination of technological capabilities and financial synergies from mergers often results in innovation and efficient capital allocation, further promoting growth. Additionally, mergers can create competitive advantages through diversification, ultimately attracting investment and contributing to overall economic expansion. As indicated above, a substantial body of evidence suggests that mergers contribute to increased productivity growth, while little evidence exists on the impact on market power (measured by markups) at the industry level.[20] Research also indicates that larger firms resulting from mergers spend more on innovation, which results in higher quality patent portfolios, and increased labour productivity.[21] Complementarities between R&D and knowledge spill-overs strongly associate with firm productivity rather than innovation, emphasizing the significance of merger-driven R&D and knowledge collaboration in enhancing overall economic performance.[22]

The challenges facing Australia’s economy should not be mis-interpreted as a suggestion that there is a need to reform Australia’s well-functioning merger regime to improve productivity growth. Instead, policymakers should more carefully consider and then address impediments related to technology adoption, taxation, industry-specific regulations, and education as key factors influencing productivity growth in the country.

As concerns the potential reform of Australia’s merger regime, policymakers should acknowledge the positive link between mergers, innovation, and increased research and development (R&D) spending by larger firms. To foster innovation, they should not deter mergers that result in efficiency gains, and greater investments in R&D and technology development. Additionally, regular monitoring and evaluation of post-merger outcomes are essential, requiring policymakers to implement mechanisms to assess impacts on productivity, market competition, and innovation. Ongoing scrutiny of merged entities ensures that anticipated benefits materialize, and potential negative consequences, such as anti-competitive practices, are promptly addressed through appropriate regulatory interventions.

C. Merger rules can be improved at the margin

The consultation by the Competition Taskforce examines whether Australia’s merger approval process has weaknesses hindering its effectiveness. If so, the Competition Taskforce should focus on the minimal solutions needed to address any weaknesses without impeding the capital flow through mergers and acquisitions in the country.

Transition towards an administrative-decision making regime (with the ACCC as the decision maker)

At the outset, it is important to note that the current judicial enforcement model works well. Maintaining this well-functioning model does not preclude a reform that would appear to address key objectives. For example, a mandatory and suspensory notification system, with upfront information requirements, could be implemented without a wholesale shift to an administrative-decision making model. However, in the event of a preference for an administrative decision making system.

In the event of a preference for an administrative-decision making system, the ACCC should make sure to have the necessary resources and expertise in conducting thorough merger investigations. Contrary to the ACCC’s position, there is an essential need for a comprehensive merit review by either the Australian Competition Tribunal with the Federal Court retaining its jurisdiction to make declarations in relation to existing statutory prohibition. Importantly, this goes beyond standard judicial review, focusing on substantive evaluation rather than a procedural review. It is useful to note that limiting merger reviews to a procedural review has been subject to intense criticism in the debate about the reform of the UK’s merger policy – leading to recent changes to the UK regime in light of concerns regarding investment in the UK.[23]

The present merger authorisation regime, distinct from informal clearance, restricts review of materials before the ACCC. Replicating this approach risks compromising the review’s integrity by limiting examination and cross-examination of expert witnesses. An amended administrative-decision making system should allow for more comprehensive and independent review mechanism. Mirroring the current merger authorisation regime would tether the merger parties’ case to ACCC decisions, hindering true impartiality. This underscores the imperative for a nuanced, impartial review process to fortify the effectiveness of merger evaluations. A full merit review system would ensure that the totality of evidence available can be tested objectively and give the decision maker on review the ability to properly consider the facts and issues relevant to the merger.

Introduction of a mandatory notification system

Data indicate that the majority of major transactions with potential competition concerns in Australia are already being voluntarily notified to the ACCC during the informal review process. The introduction of a mandatory notification system based on specified thresholds might not substantially deviate from the outcomes observed under the existing regime, as companies typically seek clearance for transactions. However, in the event that a mandatory notification regime is deemed necessary, such a regime could be implemented, but to mitigate legal and economic uncertainties, the ACCC should provide for a robust and confidential “pre-notification” pathway. Under this procedure, parties would submit concise information for mergers that technically meet notification thresholds but are not expected to pose significant competition concerns.

In practice, the ACCC could amend its Merger Guidelines, furnishing comprehensive instructions pertaining to the categories of mergers suitable for this process. The ACCC would preserve the authority to convert a “pre-notification” submission into a complete filing as deemed necessary, potentially adopting a phased strategy in presenting information.

Consideration of sector-specific considerations

As concerns sector-specific considerations, the ACCC has discussed the potential for a “tailored test for acquisitions by certain digital platforms.”[24] Due to the risk of subjective and misguided investigations, it is crucial to maintain the sector-agnostic nature of the merger clearance regime under Part IV of the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth). The long-standing and well-understood merger test, in place since 1992, provides a consistent analytical framework for the Substantial Lessening of Competition (SLC) test. It should be noted that the consultation paper does not explicitly propose sector-specific measures.

Technology companies, irrespective of their size, exhibit significant heterogeneity and are commonly immersed in intense competition. Globally, major technology platforms have frequently disrupted traditional sectors, fostering a climate of increased competition. Large technology firms, in particular, compete through substantial investments in R&D and innovative product offerings.[25]

We recommend that the sectoral regulatory mistakes made with the Digital Market Act enacted by the EU should be avoided. The DMA is facing criticism for the ambiguities around many of its core provisions and this is posing a risk of ineffectiveness and heightened legal disputes (with parties increasingly challenging the DMA). The recommendations that are being made to fix the DMA include a more precise delineation of the DMA’s objectives, aligning them with established competition law concepts, particularly regarding competition and contestability, judicial review, and opportunities for regulatory dialogue.[26] Accordingly, introducing sector-specific requirements in Australia, particularly for digital technology, platforms, or data, in the merger regime would jeopardise the timeless nature of the SLC test. Moreover, introducing sector-specific requirements in the merger regime would make the regulatory framework subject to frequent changes to address specific sectors, which would compromise legal certainty and erode investor confidence in Australia.

Extension of the SLC test

The ACCC is proposing an extension of the SLC test. The proposed considerations involve assessing whether an acquisition would “entrench, materially increase, or materially extend a position of substantial market power”. In addition, according to the proposal, new factors for SLC assessment include whether the merger constitutes a series of acquisitions (“creeping acquisitions”) and involves increased access to or control of data or technology.

The extension of the SLC test by a broad and unproven concept would increase legal and economic uncertainty and undermine Australia’s attractiveness to technology investments. Assessments of whether an acquisition entrenches, materially increases or materially extends a position of substantial market power would open the door for ambiguity and subjectivity in determining potential competitive effects of such series. Moreover, any entrenchment, material increase, or extension of market power causing a material anticompetitive impact is adequately covered by the existing SLC standard. Finally, market power entrenchment, material increase, or extension without a discernible anticompetitive impact will not fall within the purview of the SLC standard, and, accordingly, there is no substantiated policy rationale for imposing a prohibition in these circumstances.

Prohibiting mergers unless the decision maker is convinced that there is no likelihood of a “Substantial Lessening of Competition”

The Task Force and ACCC are contemplating changes to the current merger test, which assesses whether a transaction substantially lessens competition. This proposal effectively reverses the statutory position from allowing mergers unless they are likely to SLC to prohibiting mergers unless a decision maker is positively satisfied that they will not be likely to SLC. The proposal seems very likely to generate “false positives” by prohibiting mergers likely to have the effect of SLC without requiring conclusive evidence.

The ACCC’s proposal to amend the SLC test is inconsistent with prevailing international norms and as such contradict the underlying rationale of the considered reforms. The ACCC should persist in its role as the primary investigator of mergers, with subsequent determinations subjected to thorough examination through either the Australian Competition Tribunal or the Federal Court.

Understanding how a decision maker can be convinced of a negative proposition, especially in the context of predicting the future, is ambiguous and close to impossible to determine. The resulting lack of clarity creates challenges for an efficient and effective system for clearing mergers, posing a substantial risk to Australia’s investment attractiveness. The Competition Taskforce should carefully weigh the consequences of false positives borne solely by the parties involved in the merger. A merger enforcement regime where the ACCC can stop mergers based on not being convinced of a negative proposition is risky for any investment (domestic and foreign) in support of large-scale innovation. This risk increases when the test, which needs to be proven in a negative way, involves looking at a series of acquisitions or expanding market power, especially when there’s only a limited review of the decision.

References

[1] See Merger Reform Consultation paper of November 2023. November 2023. Available at https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-11/c2023-463361-cp_0.pdf.

[2] For a critical discussion see, e.g., Champion et al. (2023). Competition, Markups, and Inflation: Evidence From Australian Firm-Level Data. Available at http://www.chrisedmond.net/Champion%20Edmond%20Hambur%202023%20Markups%20Inflation%20Paper.pdf. Also see Weche and Wagner (2020). Markups and Concentration in the Context of Digitization: Evidence from German Manufacturing Industries. Available at https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/234580/1/wp-391-upload.pdf.

[3] See OECD (2021). Methodologies to Measure

Market Competition. Available at https://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/methodologies-to-measure-market-competition-2021.pdf.

[4] See European Commission (2025). Estimation of service sector mark-ups determined by structural reform indicators. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/publications/economic_paper/2015/pdf/ecp547_en.pdf.

[5] OECD (2024). SDBS Structural Business Statistics (ISIC Rev. 4): Productivity of SMEs and large firms. Available at https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=82736.

[6] See, e.g., OECD (2021). Intangibles and industry concentration – Supersize me. Available at https://www.oecd.org/industry/intangibles-and-industry-concentration-ce813aa5-en.htm.

[7] See, e.g., Gina Cass-Gottlieb (2021), stating that “[t]e problem of concentration is a growing one in Australia”. Gina Cass-Gottlieb, ACCC Chair, addressed the National Press Club on the role of the ACCC and competition in a transitioning economy on Wednesday 12 April 2023. Available at https://www.accc.gov.au/about-us/media/speeches/the-role-of-the-accc-and-competition-in-a-transitioning-economy-address-to-the-national-press-club-2023.

[8] See, e.g., OECD (2019). Productivity in SMEs and large firms. Available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/54337c24-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/54337c24-en.

[9] See, e.g., Amiti et al. (2023). FDI and superstar spillovers: evidence from firm-to-firm transactions. NBER working paper 31128. Available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31128/w31128.pdf.

[10] IMF (2020). Small and Vulnerable:

Small Firm Productivity in the Great Productivity Slowdown. IMF Working Paper. Available at https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/12/18/Small-and-Vulnerable-Small-Firm-Productivity-in-the-Great-Productivity-Slowdown-49964.

[11] Parliament of Australia (2021). Australia’s productivity slowdown. Rodney Bogaards, Economic Policy. Available at https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook47p/AustraliasProductivitySlowdown.

[12] See OECD (2024). OECD tax statistics. Available at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CTS_CIT.

[13] PWC (2023). Australia, Taxes on corporate income. Available at https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/australia/corporate/taxes-on-corporate-income#:~:text=All%20companies%20are%20subject%20to,reduced%20tax%20rate%20of%2025%25.

[14] OECD (2023). Services trade restrictiveness, Australia 2022. Available at https://www.oecd.org/trade/topics/services-trade/documents/oecd-stri-country-note-aus.pdf.

[15] OECD (2023). OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index. Available at https://data.oecd.org/fdi/fdi-restrictiveness.htm. For impacts of investment uncertainty, see United States Studies Centre at the University of Sydney (2021). A foreign investment uncertainty index for Australia and the United States. Available at https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-04/c2022-244363-unitedstatesstudiescentre-01.pdf.

[16] Productivity Commission of Australia (2023). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Australia’s data and digital Dividend. Available at https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report/productivity-volume4-data-digital-dividend.pdf.

[17] Productivity Commission of Australia (2017). Shifting the Dial – 5-year productivity review. Available at https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity-review/report.

[18] Productivity Commission of Australia (2023). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Advancing Prosperity. Recommendations and Reform Directives. Available at https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report/productivity-recommendations-reform-directives.pdf.

[19] Productivity Commission of Australia (2023). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Australia’s data and digital Dividend. Available at https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report/productivity-volume4-data-digital-dividend.pdf.

[20] See, e.g., Demirer and Karaduman (2022). Do Mergers and Acquisitions Improve Efficiency: Evidence from Power Plants. Available at https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/demirerkaraduman.pdf. Chen (2019). Mergers, Aggregate Productivity, and Markups. Available at https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/cbscwp/288.html. Arocena et al. (2020). Measuring and decomposing productivity change in the presence of mergers. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0377221719307180. Song-Hyun and Young-Han (2024). Does cross-border M&A improve merging firms’ domestic performances? Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1049007823001161.

[21] See, e.g., Entezarkheir and Sen (2023). Productivity, Innovation Spillovers, and Mergers: Evidence from a Panel of U.S. Firms. Available at https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/bejeap-2021-0440/html. Also see See, e.g., OECD (2021). Intangibles and industry concentration – Supersize me. Available at https://www.oecd.org/industry/intangibles-and-industry-concentration-ce813aa5-en.htm.

[22] See, e.g., Audretsch and Belitski (2020). The role of R&D and knowledge spillovers in innovation and productivity. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0014292120300234. Chen et al. (2023). Digital M&A and firm productivity in China. Available at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1544612323006980.

[23] See, e.g., Bourne (2023). Handing regulators a blank cheque will make Britain a tech turn-off. Available at https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/handing-regulators-a-blank-cheque-will-make-britain-a-tech-turn-off-8vbbbs5rq.

[24] ACCC (2021). Protecting and promoting competition in Australia keynote speech. Competition and Consumer Workshop 2021 – Law Council of Australia, 27 August 2021. Available at https://www.accc.gov.au/about-us/media/speeches/protecting-and-promoting-competition-in-australia-keynote-speech.

[25] See, e.g., Akman (2022). Regulating Competition in Digital Platform Markets: A Critical Assessment of the Framework and Approach of the EU Digital Markets Act. Available at https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/181328/7/Akman%2C%20DMA%2C%20ELR%201-12-21%2C%20SSRN.pdf. Also see Garces (2023). Regulation and Competition in Digital Ecosystems: Some Missing Pieces. Available at https://www.networklawreview.org/digital-ecosytems-missing-pieces/. A related discussion of merger policies and impacts on innovation and investments is provided by ECIPE (2023). Merger Policy, Competition and Innovation Leadership: Implications for the UK’s Investment Attractiveness. Available at https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/ECI_23_PolicyBrief_12-2023_LY02.pdf.

[26] See, e.g., Bauer, et al. (2022). The EU Digital Markets Act: Assessing the Quality of Regulation. Available at https://ecipe.org/publications/the-eu-digital-markets-act/.