Published

Intellectual Property and Biodiversity

Subjects: Trade and IP

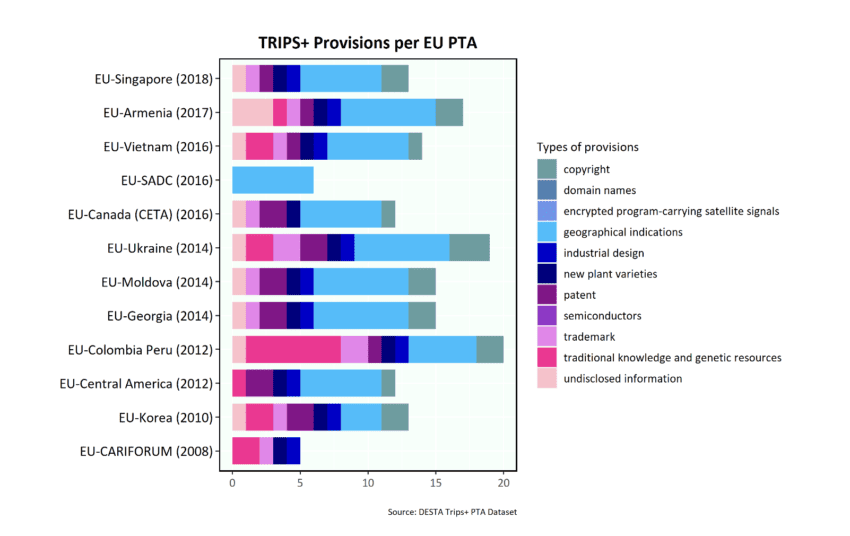

The EU-Colombia, Peru, Ecuador FTA is the EU FTA that contains most intellectual property provisions of all EU FTAs regarding the protection of ‘traditional knowledge and genetic resources’ (DESTA, 2020) as shown in Figure 1, detailed under Title VII (Intellectual Property), Chapter 2, “Protection of biodiversity and traditional knowledge”. The big question is whether this approach could work to help strengthen and preserve biodiversity, also from a trade-impact perspective.

Figure 1: Types of TRIPS+ provisions in EU Free Trade Agreements

Source: DESTA database

The relevance of Intellectual Property Rights for biodiversity

A perceived tension is that IP could be seen as going against the philosophy of indigenous and local communities that knowledge and information should be shared. While it is true that IP protects the unauthorised commercial use of knowledge that is patented by the patent-holder, IP does not prevent the spread of the information or knowledge – in fact sharing the knowledge so it becomes publicly available is part of a patent application.

An important legal argument in favour of the use of IPR to protect biodiversity lies in the argument of Fuller (2005) that protections for traditional knowledge under IPRs fit substantially the principles for legality.[1] This proves helpful in considering the recognition of traditional knowledge under the IP regimes: “The [Nagoya] Protocol may be seen as complementing the recognition of rights of indigenous communities to the maintenance, control, protection and development of traditional knowledge and IP relating to traditional knowledge” (Phillips, 2016).[2] This is even more important when sequencing, cataloguing and characterising the genomes of viruses and eucaryotes on the planet takes digital flight (e.g. through the Earth BioGenome Project and the Global Virome Project).[3] [4] These projects allow resulting sequences to be used for R&D purposes and to be made publicly available through online databases without ever requiring access to the physical-biological resources from which the sequences were obtained.[5]

In addition, Article 27 of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) relating to the protection of moral and material interest in intellectual creations applies as much to traditional knowledge as to other creations. In this way IPR give indigenous and local communities – via procedural obligations that require the engagement of these indigenous communities – a say and strengthen their case for forms of self-governance and consent. This would allow developing countries to defend themselves better against bio-piracy.[6]

The road ahead

From the above review, it becomes clear that IPR could work to help strengthen and preserve biodiversity in the areas where it is concentrated. However, for IP – via EU Free Trade Agreements – to work in support of biodiversity, it is important that three other aspects related to EU FTAs and biodiversity are looked into:

1. The impact (both ex ante and ex post) of an EU FTA on biodiversity on the ground needs to be adequately assessed and measured, in particular in terms of whether IP supports biodiversity and whether there is a fair distribution of economic benefits. An elaborate system of ex ante and ex post trade sustainability impact assessments (Trade SIA) has been set up. A DG Environment project called “Methodology for improved assessments of the impact of Trade Agreements on biodiversity” has suggested ways forward to focus the Trade SIA assessments more on biodiversity effects.

2. The Chief Trade Enforcement Officer (CTEO), appointed in 2020 in order to follow-up on the implementation of the FTA commitments, based on the impact assessment work, should also focus more on whether the EU FTAs achieve their goals – for example regarding the impact of EU FTAs on biodiversity.

3. For IP provisions in EU FTAs to strengthen biodiversity, developing countries also need to have appropriate capacities and resources in the form of an adequately educated and equipped court system with sufficient knowledge of IP law and biodiversity. Peru is an example in case. Peru has taken a strong stance against biopiracy.[7] And the Peruvian Anti-Biopiracy Commission has resolved various cases of claims related to native plants, invalidating several patents. However, the number of patent filings is much larger than the number of cases the Commission can deal with. The EU should therefore also consider flanking the IP provisions on traditional knowledge and genetic resources in its FTAs with other forms of support.

4. In addition, patent and copyright systems are not sufficiently adequate to address several forms of traditional knowledge and should be complemented by including pre-existing community protocols or customary law into the IP framework. This includes the use of integrated definitions like “commercialisation” (including filing, obtaining or transferring IPRs domestically or abroad), “community intellectual property rights” that recognise community rights over traditional knowledge, “community protocols” that incorporate indigenous communities’ customary law into the IP framework as procedural norms.

[1] Fuller, L. Morality of Law 39, 46–90; Colleen Murphy, ‘Lon Fuller and the Moral Value of the Rule of Law’ (2005) 24 Law and Philosophy 239, 240–241.

[2] Phillips, F.-K. (2016). Intellectual Property Rights in Traditional Knowledge: Enabler of Sustainable Development. Utrecht Journal of International and European Law, 32(83), pp.1–18. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ujiel.283

[3] Lewin, H.A. et al., ‘Earth BioGenome Project: Sequencing Life for the Future of Life’ (2018) 115 (17) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 4325.

[4] Carroll, D. et al., ‘The Global Virome Project’ (2018) 359 (6378) Science 872.

[5] Belisario Zorzal, P., R. Curi Hauegen, F. Pires Pimenta, (2020), “Biodiversity and the patent system: the Brazilian case”, Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, 2020, Vol. 15, No. 10.

[6] Tobin, B. (2009) ‘Setting Traditional Knowledge Protection to Rights: Placing Human Rights and Customary Law at the Center of Traditional Knowledge Governance’ in Evanson Kamau and Gerd Winer (eds), Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge and the Law: Solutions for Access and Benefit Sharing (2009) 107.

[7] Peru Is Leader Against Biopiracy – Intellectual Property – Peru (mondaq.com)

We invite you to join the discussion on social media using #IPinEUFTAs and bookmarking our Trade and IP Project webpage to capture all future updates.