Published

European Strategic Autonomy – What Role for Europe’s Fragmented Single Market?

By: Matthias Bauer

Subjects: Digital Economy EU Single Market European Union

30 years after the establishment of the European Single Market, regulatory convergence reversed or came to a halt in the EU. This lack of integration is the expression of a “Single Market Fatigue”. It may ultimately hamper the EU’s ability to reduce its reliance on the United States and China, as charted in the European Commission’s Strategic Autonomy agenda. If the EU fails to boost the free movement of goods, services, people, and capital, the new policies towards industrial or technological sovereignty will only create additional costs for businesses and society and exacerbate the productivity and technology gap with the US.

This short article outlines key challenges for European economic integration and the EU’s failure to catch up with other major regions on business activity and key technologies. It illustrates the problem of regulatory fragmentation, especially in services sectors, and Europe’s huge business activity gap vis-à-vis the US. It concludes that achieving the ambitions for Strategic Autonomy – in broad terms, the EU’s ability to chart its own course in line with its values – critically relies on achieving a real European continental market.

Box 1: Key take aways

The Single Market Fatigue

January 1, 1993, marks the date of the formal establishment of the “European Single Market”. 30 years since its dawn, the Single Market is to the largest extent incomplete. EU legislation expanded tremendously over the past decades, but common and uniformly applied EU policies are still the exception rather than the rule. EU Member States keep sticking to their own versions of horizontal and sector-specific laws.

This is at odd with the current zeitgeist in Brussels. In her State of the Union address from September 2020, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen reiterated that Europe’s “Single Market is all about opportunity – for a consumer to get value for money, a company to sell anywhere in Europe and for industry to drive its global competitiveness.” Likewise, European Commission Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager highlighted that only a common European market gives European businesses room to grow and to innovate. Referring to Europe’s underperformance in digital industries, Mrs Vestager stated that “[o]ne of the reasons why we don’t have a Facebook and we don’t have a Tencent is that we never gave European businesses a full single market where they could scale up […] Now when we have a second go, the least we can do is to make sure that you have a real single market.”

The Single Market is often said to be the EU’s greatest achievement. Indeed, since the 1980s, Europe’s common market advanced in many impressive ways. Inspired by the principle of mutual recognition for goods, Brussels and most Member State capitals kept cultivating a political climate that in general embraces the idea of a borderless European market for goods and services, capital, and workers.

And yet, 30 years after its formal establishment, the Single Market is to the largest extent incomplete, lacking common and uniformly applied EU policies in economic and social policymaking. About a decade ago, at the time of its 20th anniversary, EU officials already recognised a crisis of the Single Market. Following the conclusions of the famous Monti Report of 2010 (A new strategy for the Single Market: At the service of Europe’s Economy Strategy), many saw an urgent need for action to create a real European level-playing field for businesses and workers. The integration fatigue, however, continued to prevail.

EU policymaking has so far been characterised by an inflation of Directives which allow for national discretion in implementation and enforcement. New layers of EU regulation created an unparalleled patchwork of horizontal and sector-specific Member State laws. For businesses and consumers, the Single Market remains a complex web of business, tax and labour regulations, which vary from country to country, creating confusion and legal uncertainties. In 2016, a report by the European Parliament found that the “costs of a slow reform process and vague initiatives with uncertain time horizons in the area of e-commerce alone amount to EUR 748 billion.“

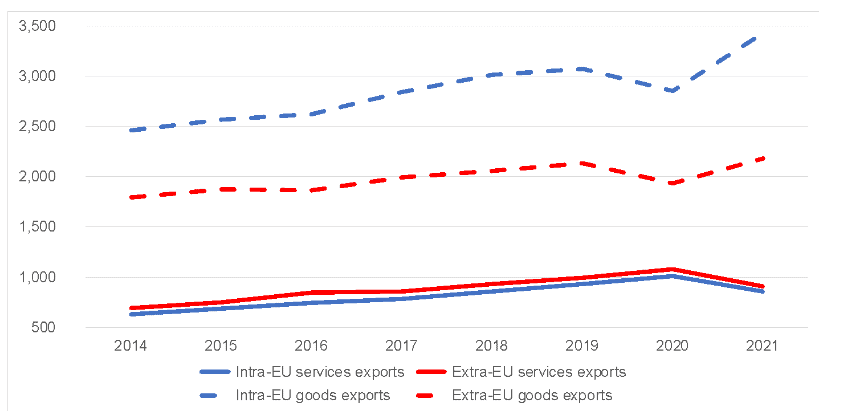

Services sectors, which together account for 65% of EU27 GDP, are a case in point. As shown by Figure 1, intra-EU services exports show the same growth trend as extra-EU services exports. Contrary to intra-EU trade in goods, which outperforms extra-EU trade (with non-EU countries) intra-EU services exports only kept growing in line with trends in global demand. In many services sectors, national policies, disproportionate regulatory restrictions and weak competition are preventing consumers and firms from harnessing the full benefits of EU integration.

Figure 1: Development of intra-EU and extra-EU goods and services exports, 2014-2021, in EUR bn

Source: Eurostat

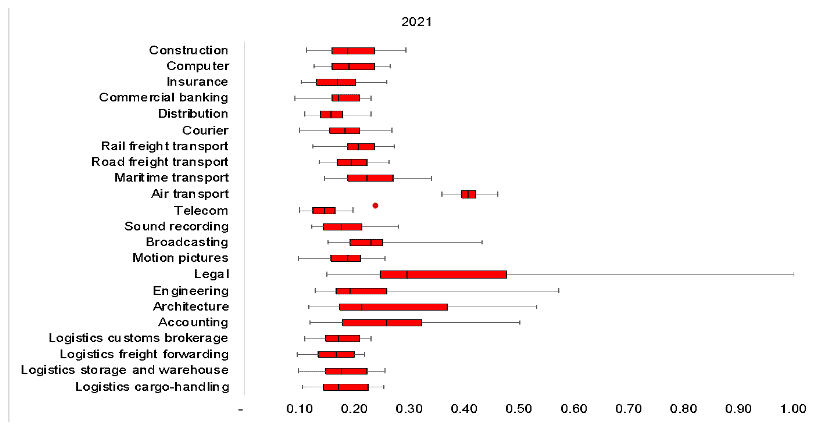

For construction and logistics to computer and telecommunications services, OECD services trade restrictiveness data demonstrate that Europe’s Single Market did not advance during the past decade. EU policy has not succeeded in harmonising the rules for services, let alone initiating a process of liberalisation and convergence. In most services sectors, Member State regulations became more restrictive, both at the lower and the upper end of the restrictiveness spectrum.

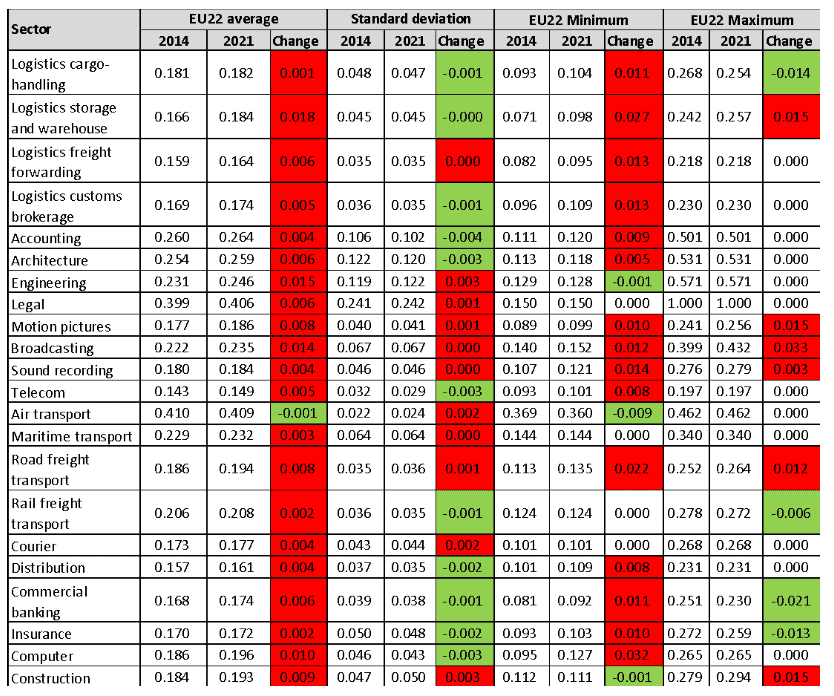

In many services sectors, Member States are still free to determine their own regulation and how open they want to be from imports from other EU countries (see Figure 2 and Table 1). Take telecoms, for example: The EU currently does not have a unified mobile telecommunications market, which hampers the deployment of broadband and 5G in the Member States. Other examples are differences in access conditions in markets for regulated professions, education, broadcasting, logistics services (e.g. freight cabotage), and healthcare services. Similar trends can be observed for many product markets regulations (PMR) and, importantly, horizontal policies, such as sales taxes and VAT, corporate taxes, labour market policies, and environmental standards in the Member States.

Countless studies confirm that regulatory complexity is challenging for any business, especially SMEs. For example, the SME Envoy Network highlights that “the Single Market is neither perfect nor complete”. Member State law is characterised by an increasing number of new regulations, overlapping policies escalating the complexity of EU and Member States’ legal frameworks. Each year, as noted by the authors, “the amount of national technical regulation keeps piling up which makes it more difficult for SMEs to expand their activities across Europe. At the European level, SMEs also experience confusion from partially overlapping rules. This means that SMEs do not necessarily know which rules apply to them – they simply do not understand which rules to follow.”

Figure 2: Statistical distribution of regulatory restrictiveness in 2021

Source: OECD STRI database. Bars represent EU sample minimum, 1st quartile, median, 3rd quartile, and maximum values.

Table 1: Development of EU services trade restrictiveness and regulatory fragmentation, 2014 to 2021

Source: OECD STRI database. Red fill indicates increase in regulatory restrictiveness and regulatory heterogeneity respectively.

The number of businesses in the US is twice as high as in the EU

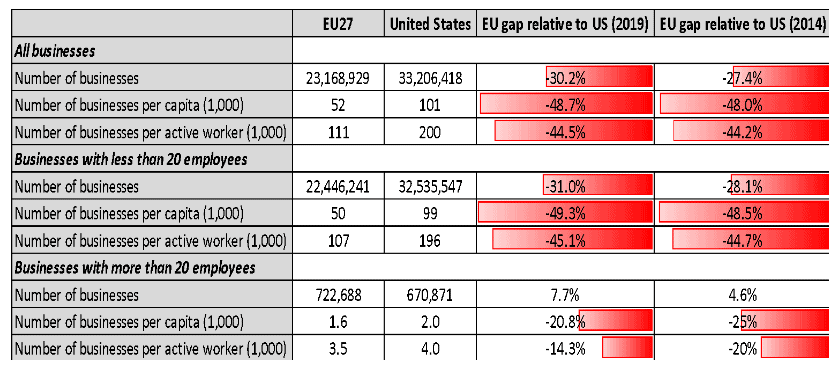

The lack of harmonised rules does not help the EU to catch up with business, competition and innovation dynamics in major other jurisdictions such as the US (and China – whose GDP will be more than twice as high as EU GDP in 2050). Business statistics demonstrate that despite a much smaller labour force, the US is home to a much higher number of businesses than the EU. The EU’s deficit in the absolute number of established businesses relative to the US was 30% in 2019, increasing from 27% in 2014. It amounts to close to 50% on a per capita basis. In other words, the number of businesses per capita in the US is twice as high as in the EU. The EU’s deficit in SMEs with less than 20 employees is even higher, increasing from 48.5% in 2014 to 49.3% in 2019 (see Table 2).

Due to differences in the definition of large companies, it is difficult to depict precise trends and patterns for large and very large businesses. However, data suggest that the average number of employees of a large US company (300 employees or more) is about twice as high as the average number of employees of a large company that is based in the EU (companies with 250 employees or more), indicating that it is much easier for US companies to scale than for companies in the EU. Adding EU policy fragmentation, it does not come as a surprise that the number of European scale-ups is still less than a third of those in the US. Europe is expected to face a large and growing corporate performance challenge, reflected by lower productivity, lower profit margins, lower investments, and less tech creation compared to US counterparts.

Table 2: The EU’s “Business Gap” vis-à-vis the US

Source: Eurostat and US Census. Eurostat data taken from the annual enterprise statistics by size class for the entire business economy ex financial and insurance services. US Census data extracted from the Statistics of U.S. Businesses (SUSB) and US Non-employer Statistics (NES) databases. Eurostat data include micro businesses (0-9 employees). NES data represent businesses that are reported to have no paid employees.

Political ambitions for Strategic Autonomy must account for systemic – legal – obstacles to economic integration and business activity in the EU

Ernest Hemmingway, the American writer, once described bankruptcy as happening “gradually, then suddenly”. Several studies of the state of the EU – its productivity, technology and investment gap – point to similar pattern, also referred to as a slow-motion corporate and technology crisis.

Strategic Autonomy has emerged as an influential concept for EU policymaking. It is partly intended to improve EU value chains, partly to deal with new growth poles that challenge the EU’s economic position, some with different economic models, and notably China. However, many policymakers in Europe still have a confused vision about the policy conditions required for Europe to grow its economy and technological capacities. A conventional wisdom that has emerged over the past years supposes that whatever economic underperformance that can be ascribed to Europe is a consequence of the superior performance of US technology companies, which, so the story goes, are simply too competitive or too innovative for Europe’s economy to prosper on the back of indigenous innovation.

The most pressing structural impediment for European businesses to develop and reach scale is not necessarily the level of policy restrictiveness, but the level of regulatory fragmentation across EU Member States. Due to fragmented regulatory frameworks in many horizontal and (services) sector-specific policies, it is difficult for innovative businesses to contest traditional industries, e.g., by digitalising old-economy business models.

At the same time, powerful incumbents that have successfully adopted to national laws and regulatory procedures often prevent regulatory change. Regulatory fragmentation and incumbency protection are intertwined. Both can be major sources of inefficient resource allocation in many industries – irrespective of whether they find themselves in primary sectors, manufacturing or services industries.

The paramount task for European policymakers to achieve Strategic Autonomy objectives should be to eliminate policy fragmentation that holds European business models back from transforming European economies faster to become more competitive.

Europe at crossroads – need for a new political mindset

In 1985, when the European Commission called on national governments to complete the internal market, stakes were considered high: “Europe stands at the crossroads. We either go ahead – with resolution and determination – or we drop back into mediocrity. We can now either resolve to complete the integration of the economies of Europe; or, through a lack of political will to face the immense problems involved, we can simply allow Europe to develop into no more than a free trade area.” (White Paper for the European Council, Milan, June 1985).

In the last 30 years ,however, lip service paid to render the EU the world’s “most integrated market” did not result in a removal of regulatory obstacles to cross-border commerce. The model of “one Directive + 27 different Member State laws” continues to leave European companies with a structural disadvantage compared to companies that operate in the world’s largest, most populous and more complete markets – where businesses can access hundreds of millions of customers at much lower costs.

With the benefit of hindsight, the EU institutions may not be in the best position to lead in the process of completing the Single Market. Economic integration towards a “real” Single Market requires a political mindset change at the EU and Member State level. It also requires new political leadership among Member State governments. The mindset change may involve disengagement from the Franco-German-centric modes of economic integration, which in the past failed to promote common rules for all EU Member States.